Sukinda Pata: a Case-Study on Changing Perspectives of Commons and Commons Management Due to Industrialization in Odisha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Union Bank of India -Information of Bank Mitr / Bcs (Banking Correspondents) Operating Location

Union Bank of India -Information of Bank Mitr / BCs (Banking Correspondents) Operating Location. Location of BC Name of Bank Gender Full Postal Address with Pincode (Bank Mitr Bank Mitr Mobile No. Photo of Bank Mitr S.No Name Of Bank Vendor Name of State Name of District Mitr (M/F/O) Fixed location SSA) ( 10 Digit). (JPG/PNG format) Longitude Latitude 1 Union Bank of India Coromandel Odisha Angul Basanta Sahu M At/Post- K-Bentapur Block- Angul Dist- Angul PIN 9938543979 20.8071505 85.1604581 NO- 759132 2 Union Bank of India Coromandel Odisha Angul Manish Rout M At/Post- Tentuloi Block- Talcher Dist- Angul PIN NO- 9178057766 20.8691448 85.1732866 759103 3 Union Bank of India Coromandel Odisha Bhadrak Parbati Jena F At/Post- Kedarpur Block- Bhadrak Dist- Bhadrak PIN 8895464141 21.04733 86.5877749 NO- 756127 4 Union Bank of India Coromandel Odisha Bhadrak Sushanta Mishra, M At/Post- Kedarpur Block- Bhadrak Dist- Bhadrak PIN 9937553326 21.0483001 86.58108 NO- 756127 5 Union Bank of India Coromandel Odisha Bhadrak No need BCA At/Post- Kedarpur Block- Bhadrak Dist- Bhadrak PIN NA NA Na Kedarpur NO- NA 6 Union Bank of India Coromandel Odisha Dhenkanal Rohit Kumar Behera M At/Post- Mangalpur Block- Dhenkanal Dist- 8908077981 20.64235 85.563265 Dhenkanal PIN NO- 759015 7 Union Bank of India Coromandel Odisha Dhenkanal Binodini Parida, F At/Post- Baruan Block- K Nagar Dist- Dhenkanal PIN 9556876784 20.7936049 85.592625 NO- 759026 8 Union Bank of India Coromandel Odisha Dhenkanal Sumita Sathapathy, F At/Post- Baruan Block- K Nagar Dist- Dhenkanal -

Mapping the Nutrient Status of Odisha's Soils

ICRISAT Locations New Delhi Bamako, Mali HQ - Hyderabad, India Niamey, Niger Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Kano, Nigeria Nairobi, Kenya Lilongwe, Malawi Bulawayo, Zimbabwe Maputo, Mozambique About ICRISAT ICRISAT works in agricultural research for development across the drylands of Africa and Asia, making farming profitable for smallholder farmers while reducing malnutrition and environmental degradation. We work across the entire value chain from developing new varieties to agribusiness and linking farmers to markets. Mapping the Nutrient ICRISAT appreciates the supports of funders and CGIAR investors to help overcome poverty, malnutrition and environmental degradation in the harshest dryland regions of the world. See www.icrisat.org/icrisat-donors.htm Status of Odisha’s Soils ICRISAT-India (Headquarters) ICRISAT-India Liaison Office Patancheru, Telangana, India New Delhi, India Sreenath Dixit, Prasanta Kumar Mishra, M Muthukumar, [email protected] K Mahadeva Reddy, Arabinda Kumar Padhee and Antaryami Mishra ICRISAT-Mali (Regional hub WCA) ICRISAT-Niger ICRISAT-Nigeria Bamako, Mali Niamey, Niger Kano, Nigeria [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ICRISAT-Kenya (Regional hub ESA) ICRISAT-Ethiopia ICRISAT-Malawi ICRISAT-Mozambique ICRISAT-Zimbabwe Nairobi, Kenya Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Lilongwe, Malawi Maputo, Mozambique Bulawayo, Zimbabwe [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] /ICRISAT /ICRISAT /ICRISATco /company/ICRISAT /PHOTOS/ICRISATIMAGES /ICRISATSMCO [email protected] Nov 2020 Citation:Dixit S, Mishra PK, Muthukumar M, Reddy KM, Padhee AK and Mishra A (Eds.). 2020. Mapping the nutrient status of Odisha’s soils. International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) and Department of Agriculture, Government of Odisha. -

Kamarda Chromite Mines of M/S B

APPENDIX I (See Paragraph -6) FORM I (a) I. Basic Information S. No Item Details Kamarda Chromite Mines of M/s B. C. Mohanty & Sons 1. Name of the project/s Private Limited over an area of 107.24 Ha. 1 (a) Mining of Minerals 2. S. No. in the Schedule 2 (b) Mineral Beneficiation Enhancement of Production 1. ROM (Chrome Ore) from 88,000 TPA to 2,00,000 TPA Proposed capacity/area/length/ 2. Chrome Concentrate through COB Plant up to 1,00,000 to be handled/command area/ lease TPA 3 area /number of wells to be handled. w.r.to Kamarda Chromite Mines of M/s B. C. Mohanty & Sons (P) Ltd. over an ML area of 107.24 ha. located at village Kamarda, Tehsil Sukinda in Jajpur district of Odisha State. Expansion of production both ROM (Chrome Ore) and 4. New /Expansion/Modernization Chrome Concentrate. 1. 88,000 TPA of ROM (Chrome Ore) EC Obtained 2. 36,000 TPA of Chrome Concentrate EC Obtained 3. Public Hearing Completed and EC presentation given on 22.06.2016 and the proposal is deferred on the ground for carrying out detailed biological study of the Study Area 5. Existing Capacity/Area, etc. along with authentication of reports and Wild Life Location Map including Wild Life Conservation Plan in case Schedule I fauna exists in the study area for Expansion of Production of Chrome Concentrate from 36000 to 66000 by re-handling of existing OB Dump. 4. Existing Area: 107.24 Ha. 6. Category of Project i.e. ‘A’ or ‘B’ ‘A’ Category Does it attract the general 7. -

EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY No.2048, CUTTACK, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 8, 2018/KARTIKA 17, 1940

EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No.2048, CUTTACK, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 8, 2018/KARTIKA 17, 1940 DEPARTMENT OF STEEL & MINES NOTIFICATION The 6th November, 2018 Sub: Prospecting operations by the Geological Survey of India under rule 67 of MC Rules, 2016. No.8734–IV(Misc)SM-118/2018/SM. — Whereas Geological Survey of India (State Unit: Odisha) has proposed to undertake prospecting operations during 2018-19 in the following identified blocks as reported vide its letter No.1521-1523-KI (Vol-II)/ TC/ODS/2017, dated the 5th July, 2018. Block / Sl. Toposheet prospecting Bounding latitude and Blok Name Stage Mineral District No. No. area in Sq. Longitude K.M. (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) General exploration for 21˚56'23.49"N to iron ore in Alaghat West 1 G2 Iron Ore Sundargarh 73G/5 0.5 21˚55'48.79"N Block Sundargarh 85˚17'42.81"E:85˚18'33.58"E district, Odisha (G2) General exploration for 21˚58'11.91"N to iron ore in Nuagan West 2 G2 Iron Ore Kendujhar 73G/5 0.65 21˚58'41.89"N 85˚15'48.68"E Block Kendujhar district, to 85˚16'35.80"E Odisha (G2) Prelimnary exploration for Iron ore in parts of 21˚48'44.49"N to 3 Kedesala northeast G2 Iron Ore Sundargarh 73G/1 1.00 21˚49'34.91"N 85˚12'43.23"E Block, Sundargarh to 85˚13'46.08"E district, Odisha(G2) Prelimnary exploration for Iron ore in 21˚57'07.80"N to Gandhalpada West Kendujhar & 4 G3 Iron Ore 73G/5 1.50 21˚58'16.41"N 85˚16'26.10"E Block, kendujhar and Sundargarh to 85˚17'14.67"E Sundargarh district, Odisha (G3) Reconnoitory survey for iron and manganese ore 21˚40'09"N to 21˚31'10.4"N 5 -

Environmental Impact Assessment for Proposed Expansion of Odisha Waste Management Project at Kanchichuan (V), Sukinda (T), Jajpur (D), Odisha

Environmental Impact Assessment for Proposed Expansion of Odisha Waste Management Project at Kanchichuan (V), Sukinda (T), Jajpur (D), Odisha (Final Report) Submitted by Odisha Waste Management Project (OWMP) Consultant Ramky Enviro Services Private Limited January 2019 Environmental Impact Assessment for Proposed Expansion of Odisha Waste Management Project at Kanchichuan (V), Sukinda (T), Jajpur (D), Odisha Final Report Submitted To Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change Indira Paryavaran Bhawan, Jor Bagh Road, New Delhi - 110003 Submitted by Odisha Waste Management Project (OWMP) Plot No: 420/648/1, Kanchichuan Village, Jajpur District, Odisha. Consultant Ramky Enviro Services Private Limited Ramky Grandiose, Gachibowli, Hyderabad (NABET Certificate No: NABET/EIA/1518/SA 061) January 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS EIA of Odisha Waste Management Project (OWMP) at Sukinda, Jajpur District, Odisha Table of Contents QCI/NABET Certificate Declaration of Experts Terms of Reference (TOR) TOR Compliance Chapter No. Title Page No. Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Introduction 1.1 1.2 Purpose of Report 1.2 1.3 Identification of Project and Project Proponent 1.3 1.3.1 Project 1.3 1.3.2 Project Proponent 1.4 1.3.3 Ramky Group Waste Management Division 1.4 1.4 Brief description of nature, size, location of the project and its importance 1.6 to the country and region 1.4.1 Importance of the Project 1.8 1.5 Scope of the Study 1.11 1.5.1 EIA Report 1.15 Chapter 2 Project Description 2.1 Type of the project 2.1 2.2 Need for the Project 2.2 2.2.1 Justification -

Jajapur District 407851 1827192 349687 1416953 86 78

Proportion of NFSA 2011 Census NFSA Coverage Coverage wrt. 2011 Census Population District/Block/GP % of % of Houeholds Population Ration Cards Beneficiaries Households Population JAJAPUR DISTRICT 407851 1827192 349687 1416953 86 78 BARACHANA BLOCK 53665 234541 43886 172469 82 74 ACHUTI BASANT 664 2783 586 2385 88 86 ANAKA 2254 9408 1937 7237 86 77 ARAKHAPUR 1144 5348 1106 4429 97 83 BADABALIKUDA 1003 4084 746 2834 74 69 BADACHANA 2573 10754 2088 7913 81 74 BADAGHUMURI 1458 5884 1157 4528 79 77 BALICHANDRAPUR 1410 6513 1161 4016 82 62 BALIPADIA 1042 3999 743 3046 71 76 BANDALO 1278 5476 1022 3747 80 68 BANTALA 1566 6693 1190 4494 76 67 BARAPADA 800 3418 622 2477 78 72 BHARATPUR 1715 7278 1409 5894 82 81 BHUSANDHAPUR 1055 5040 872 3351 83 66 BIKRAMTIRAN 2856 11381 2263 8515 79 75 BYREE 833 3639 528 2011 63 55 CHAMPAPUR 1178 4843 892 3470 76 72 CHANDITAL 1212 5647 1062 4322 88 77 CHARINANGAL 2089 10014 1872 7519 90 75 CHHATIA 2491 10639 2292 8245 92 77 DARPAN 1454 7493 1391 5618 96 75 DHANMANDAL 1118 4911 1059 3635 95 74 GOPALPUR 1481 6478 1335 5675 90 88 KAIMATIA 1017 4588 973 4041 96 88 KOLANGIRI 1126 5058 950 3714 84 73 KUNDAL 1376 6228 1218 4843 89 78 MAJHIPADA 1194 5068 932 3997 78 79 MANDUKA 1371 6147 1107 4586 81 75 NALIPUR 2331 10372 1988 8226 85 79 PARIA 1114 4683 697 2634 63 56 RADHADEIPUR 1232 4979 908 3306 74 66 RAIPUR 1467 5650 949 3757 65 66 SALAPADA 1444 6316 1232 4804 85 76 SAMIA 1448 6626 1330 5231 92 79 SAUDIA 1782 7621 1300 5220 73 68 SIHA 1347 6488 1140 4716 85 73 SOLARA 705 3125 661 2472 94 79 SUNGUDA 2037 9869 1455 5838 71 59 Proportion of NFSA 2011 Census NFSA Coverage Coverage wrt. -

District Mineral Foundation Sundargarh, Odisha

INDICATIVE PLAN DISTRICT MINERAL FOUNDATION SUNDARGARH, ODISHA Centre for Science and Environment Indicative plan district mineral foundation, Sundergarh, Odisha report.indd 1 11/01/18 3:24 PM © 2018 Centre for Science and Environment Published by Centre for Science and Environment 41, Tughlakabad Institutional Area New Delhi 110 062 Phones: 91-11-29955124, 29955125, 29953394 Fax: 91-11-29955879 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cseindia.org Indicative plan district mineral foundation, Sundergarh, Odisha report.indd 2 11/01/18 3:24 PM INDICATIVE PLAN DISTRICT MINERAL FOUNDATION SUNDARGARH, ODISHA Centre for Science and Environment Indicative plan district mineral foundation, Sundergarh, Odisha report.indd 3 11/01/18 3:24 PM Indicative plan district mineral foundation, Sundergarh, Odisha report.indd 4 11/01/18 3:24 PM INDICATIVE PLAN DISTRICT MINERAL SUNDARGARH, ODISHA Contents PREFACE ................................................................................................................................................................... 6 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ..................................................................................7 SECTION 2: BACKGROUND OF THE DISTRICT ................................................................................10 SECTION 3: SITUATION ANALYSIS THROUGH STOCK-TAKING ..........................................15 SECTION 4: SITUATION ANALYSIS THROUGH PARTICIPATORY RURAL APPRAISAL .............................................................................................................53 -

MINUTES of the 55Th MEETING of the STATE GEOLOGICAL PROGRAMMING BOARD HELD on 8TH AUGUST 2019 at BHUBANESWAR

MINUTES OF THE 55th MEETING OF THE STATE GEOLOGICAL PROGRAMMING BOARD HELD ON 8TH AUGUST 2019 AT BHUBANESWAR 55.01.00 The 55th meeting of the State Geological Programming Board (SGPB) was organized under the chairmanship of Sri R. K. Sharma, IAS, Additional Chief Secretary to Government of Odisha, Steel & Mines Department on 8th August 2019 in the Convention Hall of Hotel Mayfair, Bhubaneswar. The list of the participants is enclosed as ANNEXURE-I. 55.02.00 WELCOME ADDRESS BY THE DIRECTOR OF GEOLOGY, ODISHA & MEMBER SECRETARY, SGPB. Smt A.B Mishra, Director of Geology, Odisha and Member Secretary, SGPB extended hearty welcome to Sri R. K. Sharma, IAS, Additional Chief Secretary to Government, Steel & Mines Department and Chairman SGPB, Sri Deepak Mohanty, IFS, Director of Mines, Odisha, Sri L. L Vishwakarma, Dy. Director General, GSI, (SU) Odisha, Sri R. Veenil Krishna, IAS (M.D), OMC and all the delegates & participants in the 55th SGPB meeting. The Member Secretary emphasized on the role of SGPB and contribution of the member organizations for the mineral development of the state. State Geological Programming Board (SGPB) meeting is being congregated in the similar forum as Central Geological Programming Board (CGPB) to finalize the Annual Field Programme of the Directorate of Geology, Odisha after detailed discussion and deliberation by participating organizations. The objective of the SGPB is to recommend the Government of India regarding any issue that needs special attention for the mineral development of the state. She informed the house regarding the achievements of the 15 investigations undertaken by the Directorate of Geology during the year 2018-19 in accordance with the resolution of 54th SGPB. -

Orissa Review

ORISSA REVIEW VOL. LXVII NO. 5 DECEMBER - 2010 SURENDRA NATH TRIPATHI, I.A.S. Principal Secretary BAISHNAB PRASAD MOHANTY Director-cum-Joint Secretary LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Bikram Maharana Production Assistance Debasis Pattnaik Sadhana Mishra Manas R. Nayak Cover Design & Illustration Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Manoj Kumar Patro D.T.P. & Design Raju Singh Manas Ranjan Mohanty Photo The Orissa Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Orissa’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Orissa Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Orissa. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Orissa, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Orissa Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. E-mail : [email protected] Five Rupees / Copy [email protected] Visit : http://orissa.gov.in Contact : 9937057528 (M) CONTENTS Shree Mandir 1 Good Governance 3 Preamble Census Administration-Now And Then i Census Operations, 2011 11 ii Census of India, 1931 (Bihar and Orissa) 15 iii The Census Act,1948 19 History & Geographical Spread of Census i Census in Different Countries of the World 25 ii History of Indian Census 36 Portraits - India and Orissa i India Profile 45 ii Orissa-Population Portrait 2001 61 iii Orissa-Housing Profile 65 Portraits - Districts -

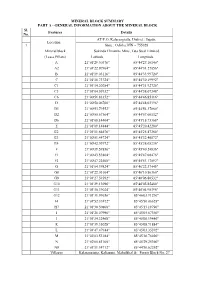

Sukinda Chromite Block Summary

MINERAL BLOCK SUMMARY PART A - GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE MINERAL BLOCK Sl. Features Details No. AT/P.O. Kalarangiatta, District : Jajpur, Location 1 State : Odisha, PIN – 755028 Mineral block Sukinda Chromite Mine, Tata Steel Limited (Lease Pillars) Latitude Longitude A 21°01'29.30376" 85°44'27.10140" A2 21°01'22.97964" 85°44'31.27056" B 21°01'19.03116" 85°44'33.99720" C 21°01'16.73724" 85°44'30.19992" C1 21°01'14.20284" 85°44'31.92720" C3 21°01'04.93932" 85°44'38.07348" C6 21°00'51.83352" 85°44'46.85316" D 21°00'50.06700" 85°44'48.03396" D1 21°00'53.79552" 85°44'54.37860" D2 21°00'55.67364" 85°44'57.60132" D6 21°01'08.14404" 85°45'18.73368" E 21°01'09.14844" 85°45'20.42280" E2 21°01'01.64676" 85°45'25.47360" E3 21°00'51.44724" 85°45'32.40072" E4 21°00'42.93972" 85°45'38.05236" F 21°00'39.59856" 85°45'40.24836" F1 21°00'43.53804" 85°45'47.08476" F2 21°00'47.22408" 85°45'53.17092" G 21°01'04.39824" 85°46'22.37448" G8 21°01'22.03104" 85°46'10.56360" G9 21°01'27.59592" 85°46'06.86532" G10 21°01'29.13096" 85°46'05.85480" G11 21°01'30.39024" 85°46'04.98396" G12 21°01'31.99656" 85°46'03.91296" H 21°01'52.37472" 85°45'50.06628" H7 21°01'30.50868" 85°45'13.19796" I 21°01'26.07996" 85°45'05.67360" J 21°01'34.32468" 85°45'00.19440" K 21°01'39.35028" 85°45'08.71884" L 21°01'47.47944" 85°45'03.35592" M 21°02'03.53184" 85°45'30.76020" N 21°02'05.81100" 85°45'29.25360" N9 21°01'31.34712" 85°44'30.62292" Villages Kalarangiatta, Kaliapani, Mahulkhal & Forest Block No. -

Assessment of Chromium Pollution at Baula Mines, Orissa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ethesis@nitr ASSESSMENT OF CHROMIUM POLLUTION AT BAULA MINES, ORISSA A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF TECHNOLOGY IN MINING ENGINEERING BY BASANTA KUMAR KISHAN 10605010 Department of Mining Engineering National Institute of Technology Rourkela 2010 ASSESSMENT OF CHROMIUM POLLUTION AT BAULA MINES, ORISSA A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF TECHNOLOGY IN MINING ENGINEERING BY BASANTA KUMAR KISHAN 10605010 Under the Guidance of Sk. Md. Equeenuddin Department of Mining Engineering National Institute of Technology Rourkela 2010 National Institute of Technology, Rourkela CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “ASSESSMENT OF CHROMIUM POLLUTION AT BAULA MINES, ORISSA” submitted by Sri Basanta Kumar Kishan in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Bachelor of Technology degree in Mining Engineering at the National Institute of Technology, Rourkela (Deemed University) is an authentic work carried out by him under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge, the matter embodied in the thesis has not been submitted to any other University/Institute for the award of any Degree or Diploma. Date: Sk. Md. Equeenuddin Assistant Professor Dept. of Mining Engineering National Institute of Technology Rourkela, Orissa-769008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my deep sense of gratitude and indebtedness to supervisor, Sk. Md. Equeenuddin, Department of Mining Engineering, N.I.T Rourkela for introducing the present topic and for his inspiring guidance, constructive criticism and valuable suggestion throughout this project work. -

Jajpur Establishment of DTU at DHH DHH,Jajpur DHH New Const

Details of Upgradation & New Construction under NRHM taken up during 2005-2013 Sl Name of the New Const/ Up- Approved in PIP Approved Executing Block Name of the work Category Physical Status no institution gradation PIP Year amount Agency 1 Jajpur Establishment of DTU at DHH DHH,Jajpur DHH New Const. 2005-06 6.00 R&B IN PROGRESS 2 Dharmasala Up-gradationgradation of CHC AT Dharmasala CHC-Dharmasala CHC Up-gradation 2005-06 20.00 BLOCK IN PROGRESS 3 Barchana Up-gradationgradation of CHC at Badachana CHC-Badachana CHC Up-gradation 2006-07 20.00 BLOCK COMPLETED 4 Binjharpur Up-gradationgradation of CHC at Binjharpur CHC-Binjharpur CHC Up-gradation 2007-08 40.15 BLOCK IN PROGRESS 5 Badachana Repair of SC at Chatia under Badachana block Sub center SC Up-gradation 2007-08 1.00 BLOCK COMPLETED 6 Madhuban Repair of SC at Laxmipur under Madhuban block Sub center SC Up-gradation 2007-08 1.00 BLOCK COMPLETED 7 Binjharpur Repair of SC at at Arei under Binjharpur block Sub center SC Up-gradation 2007-08 1.00 BLOCK COMPLETED 8 Bari Repair of SC at Amatpur under Bari block Sub center SC Up-gradation 2007-08 1.00 BLOCK COMPLETED 9 Korei Repair of SC at Tarakot under Korei block Sub center SC Up-gradation 2007-08 1.00 BLOCK COMPLETED 10 Sukinda Repair of SC at Rantol under Sukinda block Sub center SC Up-gradation 2007-08 1.00 BLOCK COMPLETED 11 Dasarathpur Repair of SC at at Jadanga under Dasarathpur block Sub center SC Up-gradation 2007-08 1.00 BLOCK COMPLETED 12 Jajpur Repair of SC at Bichitrapur under Jajpur block Sub center SC Up-gradation 2007-08 1.00 BLOCK COMPLETED New Const.