Lace Classification System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lacemaking? No Way! You Have to Buy a Bunch of Equipme

Lacis Have you ever heard this (or said it): “Lacemaking? No way! You have to buy a bunch of equipment, learn a thousand stitches, and it takes a month of eyestrain to produce just an inch of lace!” How about this? “Handmade lace isn’t worth it; it tears up too easily, and it can’t be washed.” Or the Kiss of Death: “Lace isn’t appropriate to my time period.” Nonsense! What would you say if I told you that, for less than $20, and a weekend’s work, even a child can produce lace that is attractive and versatile, can survive repeated trips through the washing machine, and is appropriate for at least late 12th century through end of Period? Lacis is that lace. Lacis (also known as darned netting, filet lace, mezzo mandolino, and Filet Italien) is one of the oldest known lacemaking techniques. Examples of the netting itself – which even the most hardened Viking would recognize as simple fishnet -- has been found in ancient Egyptian tombs. Fine netting, delicately darned, have been found in sites dating back to the earliest days of the 14th century. It is mentioned specifically in the Ancrin Riwle (a novice nun’s ‘handbook,’ c. 1301), wherein the novice is admonished not to spend all her time netting, but to turn her hand to charitable works. Figure 1 pattern for bookmark Lacis is simply a net, such as fishnet, that has patterns darned into it. It comes in two basic categories, which categorize the kind of net used. Mondano is classic fishnet, a knotted netting where a shuttle and mesh gauge is used to make link loops together to form the net. -

Grandma's Hands by Marie Blauvelt

Grandma’s Hands by Marie Blauvelt "If you look deeply into the palm of your hand, you will see your parents and all generations of your ancestors. All of them are alive in this moment. Each is present in your body. You are the continuation of each of these people." Thich Nhat Hanh I have only a few photographs of my grandmother. She was camera shy, and anyway, not often available to pose. She was usually in the kitchen, or in the garden, or in the laundry room, or walking miles from market to market with her string bags, always busy, always working, always doing. She never fussed about her appearance, even though she was attractive and had beautiful skin, large hazel eyes and wavy grey hair spilling out of whatever pins she tried to contain it with. On her tiny shoulders and five-foot-two frame, she wore sensible garments and sturdy, comfortable shoes. Her eyeglasses were either balanced at the end of her nose, perched on top of her head, or dangling from a chain around her neck-- though this never kept her from asking us, “Dove sono i miei occhiali?” She spoke as often as possible to me in Italian, taking care to correct dialect I had picked up in listening to relatives and wincing when I spoke dialect to her in reply. She never quite learned the language of her adopted country. Or, more precisely, she never felt confident enough to speak the language aloud, and was ashamed of her thick accent, although she understood and read English well. -

Plastic Canvas Patterns

Crochet & Craft Crochet & Craft Catalog Craft Store MAY 2015 OVER 300 Step Into NEW ITEMS! Springin Style! AnniesCraftStore.com CROCHET | KNITTING | BEADING | PLASTIC CANVAS | YARN CSC5 Crazy for ➤ Crochet Chevrons page 34 Southwest Tissue Plastic Covers Canvas page 56 ➤ Isadora Scarf page 79 Paper Crafts Knit Washi Tape Cards ➤ page 53 Inside Skill Level Key 3–40 Crochet Beginner: For first-time stitchers 41–44 Crochet Supplies Easy: Projects using basic stitches 45 Crochet World & Creative Knitting Special Issues Intermediate: Projects with a variety of stitches 46–49 Home Solutions and mid-level shaping 50–53 Drawing, Painting, Paper Crafts Experienced: Projects using advanced 54 Plastic Canvas Supplies techniques and stitches 55–57 Plastic Canvas 58 Cross Stitch 59 Embroidery 60 & 61 Beading Our Guarantee If you are not completely satisfied with your 62–69 Yarn purchase, you may return it, no questions 70–72 Knit Supplies asked, for a full and prompt refund. 73–83 Knit 2 ANNIESCRAFTSTORE.COM (800) 582-6643 7 a.m.–9 p.m. (CT) Monday–Friday • 7 a.m.–5 p.m. (CT) Saturday • 9 a.m.–5 p.m. (CT) Sunday New Spring Designs for Kids! NEW! CROCHET Slumber Party for 18" Dolls The girls are having fun at their sleepover. Pattern features 4 different sleep sets, all made from baby/sport-weight and DK-weight yarns with some trims in size 10 crochet cotton or novelty yarn. Designs NEW! CROCHET Bridal Party include: a granny gown Every little girl dreams of that special wedding day. with booties, a vintage Crochet a bridal party for your 18" dolls. -

Bobbin Lace You Need a Pattern Known As a Pricking

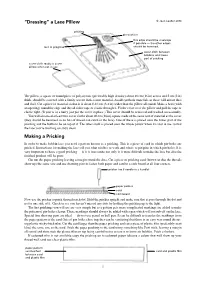

“Dressing” a Lace Pillow © Jean Leader 2014 pricking pin-cushion this edge should be a selvage if possible — the other edges lace in progress should be hemmed. cover cloth between bobbins and lower part of pricking cover cloth ready to cover pillow when not in use The pillow, a square or round piece of polystyrene (preferably high density) about 40 cm (16 in) across and 5 cm (2 in) thick, should be covered with a firmly woven dark cotton material. Avoid synthetic materials as these will attract dust and fluff. Cut a piece of material so that it is about 8-10 cm (3-4 in) wider than the pillow all round. Make a hem (with an opening) round the edge and thread either tape or elastic through it. Fit the cover over the pillow and pull the tape or elastic tight. (If you’re in a hurry just pin the cover in place.) This cover should be removed and washed occasionally. You will also need at least two cover cloths about 40 cm (16 in) square made of the same sort of material as the cover (they should be hemmed so no bits of thread can catch in the lace). One of these is placed over the lower part of the pricking and the bobbins lie on top of it. The other cloth is placed over the whole pillow when it is not in use so that the lace you’re working on stays clean. Making a Pricking In order to make bobbin lace you need a pattern known as a pricking. -

Catalogue of the Famous Blackborne Museum Collection of Laces

'hladchorvS' The Famous Blackbome Collection The American Art Galleries Madison Square South New York j J ( o # I -legislation. BLACKB ORNE LA CE SALE. Metropolitan Museum Anxious to Acquire Rare Collection. ' The sale of laces by order of Vitail Benguiat at the American Art Galleries began j-esterday afternoon with low prices ranging from .$2 up. The sale will be continued to-day and to-morrow, when the famous Blackborne collection mil be sold, the entire 600 odd pieces In one lot. This collection, which was be- gun by the father of Arthur Blackborne In IS-W and ^ contmued by the son, shows the course of lace making for over 4(Xi ye^rs. It is valued at from .?40,fX)0 to $oO,0()0. It is a museum collection, and the Metropolitan Art Museum of this city would like to acciuire it, but hasnt the funds available. ' " With the addition of these laces the Metropolitan would probably have the finest collection of laces in the world," said the museum's lace authority, who has been studying the Blackborne laces since the collection opened, yesterday. " and there would be enough of much of it for the Washington and" Boston Mu- seums as well as our own. We have now a collection of lace that is probablv pqual to that of any in the world, "though other museums have better examples of some pieces than we have." Yesterday's sale brought SI. .350. ' ""• « mmov ON FREE VIEW AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH, NEW YORK FROM SATURDAY, DECEMBER FIFTH UNTIL THE DATE OF SALE, INCLUSIVE THE FAMOUS ARTHUR BLACKBORNE COLLECTION TO BE SOLD ON THURSDAY, FRIDAY AND SATURDAY AFTERNOONS December 10th, 11th and 12th BEGINNING EACH AFTERNOON AT 2.30 o'CLOCK CATALOGUE OF THE FAMOUS BLACKBORNE Museum Collection of Laces BEAUTIFUL OLD TEXTILES HISTORICAL COSTUMES ANTIQUE JEWELRY AND FANS EXTRAORDINARY REGAL LACES RICH EMBROIDERIES ECCLESIASTICAL VESTMENTS AND OTHER INTERESTING OBJECTS OWNED BY AND TO BE SOLD BY ORDER OF MR. -

Katalog Proizvoda Product Catalogue 2007 – 2016

katalog proizvoda product catalogue 2007 – 2016 ministarstvo regionalnoga razvoja i fondova europske unije katalog proizvoda product catalogue 2007 – 2016 ministarstvo regionalnoga razvoja i fondova europske unije uvod foreword Ministarstvo regionalnoga razvoja i fondova Europske unije nastavlja The Ministry of Regional Development and European Union Funds contin- izvođenje projekta vizualnog označavanja otočnih proizvoda ozna- ues the implementation of the project related to visual marking of island kom “Hrvatski otočni proizvod” koji je pokrenut početkom 2007. s products with the “Croatian Island Product” label initiated in the begin- namjerom poticanja otočnih proizvođača u proizvodnji izvornih i kva- ning of 2007 to encourage island producers to produce original and quality litetnih proizvoda. products. Uvažavajući Nacionalni program razvitka otoka i Zakon o otocima pro- Taking into consideration the National Island Development Programme jekt je pripreman nekoliko godina. Temeljni je cilj da se identificiraju and the Islands Act, it took a couple of years to prepare the project. The i distribuiraju kvalitetni otočni proizvodi koji će kao takvi biti prepo- main objective is to identify and distribute quality island products which znati i u Hrvatskoj i izvan nje. Radi se o proizvodima koji su rezultat will be recognised as such both in Croatia and abroad. These products otočne tradicije, razvojno-istraživačkog rada, inovacije i invencije čija result from island tradition, research and development, innovation and razina kvalitete mora biti mjerljiva. Oni potječu s ograničenih otočnih invention with a quantifiable level of quality. They come from restricted lokaliteta i rade se u malim serijama. island localities and are produced in small batches. Odluku o dodjeli oznake donose neovisne tehničke komisije čiji su The decision on the award of the label is made by an independent techni- članovi priznati hrvatski stručnjaci za relevantna područja. -

Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of Terms Used in the Documentation – Blue Files and Collection Notebooks

Book Appendix Glossary 12-02 Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of terms used in the documentation – Blue files and collection notebooks. Rosemary Shepherd: 1983 to 2003 The following references were used in the documentation. For needle laces: Therese de Dillmont, The Complete Encyclopaedia of Needlework, Running Press reprint, Philadelphia, 1971 For bobbin laces: Bridget M Cook and Geraldine Stott, The Book of Bobbin Lace Stitches, A H & A W Reed, Sydney, 1980 The principal historical reference: Santina Levey, Lace a History, Victoria and Albert Museum and W H Maney, Leeds, 1983 In compiling the glossary reference was also made to Alexandra Stillwell’s Illustrated dictionary of lacemaking, Cassell, London 1996 General lace and lacemaking terms A border, flounce or edging is a length of lace with one shaped edge (headside) and one straight edge (footside). The headside shaping may be as insignificant as a straight or undulating line of picots, or as pronounced as deep ‘van Dyke’ scallops. ‘Border’ is used for laces to 100mm and ‘flounce’ for laces wider than 100 mm and these are the terms used in the documentation of the Powerhouse collection. The term ‘lace edging’ is often used elsewhere instead of border, for very narrow laces. An insertion is usually a length of lace with two straight edges (footsides) which are stitched directly onto the mounting fabric, the fabric then being cut away behind the lace. Ocasionally lace insertions are shaped (for example, square or triangular motifs for use on household linen) in which case they are entirely enclosed by a footside. See also ‘panel’ and ‘engrelure’ A lace panel is usually has finished edges, enclosing a specially designed motif. -

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identification

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace DATS in partnership with the V&A DATS DRESS AND TEXTILE SPECIALISTS 1 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Text copyright © Jeremy Farrell, 2007 Image copyrights as specified in each section. This information pack has been produced to accompany a one-day workshop of the same name held at The Museum of Costume and Textiles, Nottingham on 21st February 2008. The workshop is one of three produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A, funded by the Renaissance Subject Specialist Network Implementation Grant Programme, administered by the MLA. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audiences. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the public. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750 -1950 Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740-1890 Front cover image: Detail of a triangular shawl of white cotton Pusher lace made by William Vickers of Nottingham, 1870. The Pusher machine cannot put in the outline which has to be put in by hand or by embroidering machine. The outline here was put in by hand by a woman in Youlgreave, Derbyshire. (NCM 1912-13 © Nottingham City Museums) 2 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Contents Page 1. List of illustrations 1 2. Introduction 3 3. The main types of hand and machine lace 5 4. -

Charles A. Whitaker Auction Co. October 29-30 Session Two Lot 549-1244

Charles A. Whitaker Auction Co. October 29-30 Session Two Lot 549-1244 549 FRENCH CHINOISERIE BROCADE SILK, c. 1740-1750. Four small panels including one pieced, having ivory pattern on raspberry ground. Three pieces 24 wide x 15 1/2, 26 and 31. One 28 1/2 x 17. Holes and tears, fair. $57.50 550 LOT of SILK TEXILES, 18th C. Consisting of a red velvet panel, cushion cover and valance, the valance having shield-form tabs (applique and tassels removed), and a panel with narrow stripes in cream, dusty rose, yellow and green on a tiny checked weave. Fair. $34.50 551 THREE PRINTED COTTON PANELS, 19th C. One striped in teal with small white leaves and white with red and tan botehs, probably Persian. One English floral print. Both excellent. One large pieced panel with pomegranate trees, probably Indian, (oxidizing browns, mends and tears) poor. $103.50 552 BEADED NEEDLEWORK VICTORIAN BELL PULL. Wool flowers with beaded foliage on a ground of crystal beads having a Bohemian glass finial. (Glass cracked, backing shattered, minor bead loss) needlework intact, fair. $230.00 553 LOT of ASSORTED SMALL BEAD and NEEDLEWORK, 18th-19th C. Including two 18th C. petit point rectangles of figures in landscapes, three rectangles of needlework birds, a silk satin embroidered bag having gilt metal doves and chenille bell tassels, two framed 18th C embroideries: one eagle in tree, one basket of fruit. Good-excellent. $345.00 554 TWO PIECED SILK TEXTILES with FLORAL BROCADE, 18th C. Dusty pink damask bedcover with a serpentine floral in pastel hues, backed in blue silk, (some splits, mostly at seams). -

Sew Any Fabric Provides Practical, Clear Information for Novices and Inspiration for More Experienced Sewers Who Are Looking for New Ideas and Techniques

SAFBCOV.qxd 10/23/03 3:34 PM Page 1 S Fabric Basics at Your Fingertips EW A ave you ever wished you could call an expert and ask for a five-minute explanation on the particulars of a fabric you are sewing? Claire Shaeffer provides this key information for 88 of today’s most NY SEW ANY popular fabrics. In this handy, easy-to-follow reference, she guides you through all the basics while providing hints, tips, and suggestions based on her 20-plus years as a college instructor, pattern F designer, and author. ABRIC H In each concise chapter, Claire shares fabric facts, design ideas, workroom secrets, and her sewing checklist, as well as her sewability classification to advise you on the difficulty of sewing each ABRIC fabric. Color photographs offer further ideas. The succeeding sections offer sewing techniques and ForewordForeword byby advice on needles, threads, stabilizers, and interfacings. Claire’s unique fabric/fiber dictionary cross- NancyNancy ZiemanZieman references over 600 additional fabrics. An invaluable reference for anyone who F sews, Sew Any Fabric provides practical, clear information for novices and inspiration for more experienced sewers who are looking for new ideas and techniques. About the Author Shaeffer Claire Shaeffer is a well-known and well- respected designer, teacher, and author of 15 books, including Claire Shaeffer’s Fabric Sewing Guide. She has traveled the world over sharing her sewing secrets with novice, experienced, and professional sewers alike. Claire was recently awarded the prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award by the Professional Association of Custom Clothiers (PACC). Claire and her husband reside in Palm Springs, California. -

Project Gutenberg's Beeton's Book of Needlework, by Isabella Beeton

Project Gutenberg's Beeton's Book of Needlework, by Isabella Beeton This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Beeton's Book of Needlework Author: Isabella Beeton Release Date: February 22, 2005 [EBook #15147] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BEETON'S BOOK OF NEEDLEWORK *** Produced by Julie Barkley and the PG Online Distributed Proofreading Team. BEETON'S BOOK OF NEEDLEWORK. CONSISTING OF DESCRIPTIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS, ILLUSTRATED BY SIX HUNDRED ENGRAVINGS, OF TATTING PATTERNS. CROCHET PATTERNS. KNITTING PATTERNS. NETTING PATTERNS. EMBROIDERY PATTERNS. POINT LACE PATTERNS. GUIPURE D'ART. BERLIN WORK. MONOGRAMS. INITIALS AND NAMES. PILLOW LACE, AND LACE STITCHES. Every Pattern and Stitch Described and Engraved with the utmost Accuracy and the Exact Quantity of Material requisite for each Pattern stated. CHANCELLOR PRESS Beeton's Book of Needlework was originally published in Great Britain in 1870 by Ward, Lock and Tyler. This facsimile edition published in Great Britain in 1986 by Chancellor Press 59 Grosvenor Street London W 1 Printed in Czechoslovakia 50617 SAMUEL BUTLER'S PREFACE The Art of Needlework dates from the earliest record of the world's history, and has, also, from time immemorial been the support, comfort, or employment of women of every rank and age. Day by day, it increases its votaries, who enlarge and develop its various branches, so that any addition and assistance in teaching or learning Needlework will be welcomed by the Daughters of England, "wise of heart," who work diligently with their hands. -

The Priscilla Filet Crochet Book; a Collection of Beautiful Designs In

I (y^ \f Hollinger Corp. pH8.5 TT 820 .R7 Copy 1 tide ^risiciUaJfilet Crocijet poofe A COLLECTION OF BEAUTIFUL DESIGNS IN FILET CROCHET EQUALLY ADAPTED TO CROSS-STITCH BEADS AND CANVAS WITH Wotkin^ directions; BY BELLE ROBINSON PRICE. 25 CENTS PUBLISHED BY tETfje $rt£;ciUa ^uiilifiitjing Company 85 BROAD STREET. BOSTON. MASS. Copyright. 1911, by The PriicilU Publiihing Company. Botlon, Mau. ^ No. 1450. Pillow in Filet Crochet and Cross Stitch Embroidery See Page 5 and Figs. 12, 13, 15, 16, 18 i^ ©ci.A:u»3aoo Ho. ( 4th row — Turn with triangle, x open, 2 solid, i open, i solid, i open. Turn with $ chain. 5th row — Three open, i solid, i MmMwWM open, I triangle. 6th row — Turn with triangle, 2 open, I solid, I open. Fig. 3 Patternof Fig. 2 7th row — Turn with open, i mil 5, 3 triangle, etc. In Filet, it is a rare e.xception that has not one mm row, or more, of open meshes outside the design, and we should follow the same rule in Filet Crochet. The edge of a medallion or insert is usually covered with single crochet, three stitches over each chain of two and four stitches over each triangular mesh. This corresponds nicely with the Fig. 2 buttonhole-stitch with which the netted medallion Working Model of Pattern Fig. 3 is invariably finished. It will always be one more than a multiple of 3, Figure 6 is a model of the border of Doily, as io, 13, 16, 19, etc. 4, 7, Fig. 22, showing how to mitre the corner in a way In the 3d row (following Working Model, Fig.