Bathing Water Quality and Health Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014-2014 Programme

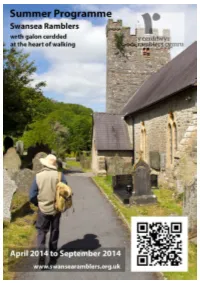

Programme – Swansea Ramblers We offer short & long walks all year around and welcome new walkers to try a walk with us. Mailing List: [email protected] 1 Swansea Ramblers wish to thank all walk leaders for providing walks for this programme. Without volunteer leaders, a programme of walks would not be possible. If you are a member of the Ramblers and would like to learn how to lead a walk, please contact the Programme Coordinator. Secretary [email protected] John France Tel: 01792-547439 Membership [email protected] Steve Hawkes Tel: 01792-360495 Programme [email protected] Roger Brown Tel: 07977-144074 Weekday Walks [email protected] Julia Robson Tel: 01792-371428 Swansea Ramblers www.swansearamblers.org.uk Ramblers GB www.ramblers.org.uk Swansea Ramblers, (formerly known as West Glamorgan Ramblers) was formed in 1981. Since then we have welcomed many new walkers to the group who come to share our enjoyment of the countryside. We organise walks across a wide area into East Wales, West Wales, Mid- Wales, and of course Gower. The Ramblers' Association is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales. Company registration number: 4458492. A registered charity in England & Wales, no: 1093577. A registered charity in Scotland, no: SC03979. Registered office: 2nd floor, Camelford House, 87- 90 Albert Embankment, London SE1 7TW. Front Cover Photograph: Llanrhidian Church v10 2 Programme Updates: www.SwanseaRamblers.org.uk Keeping in Touch We occasionally send out emails about social events and to let you know what’s happening in the group. -

THE STORY of GLAMORGAN Great Deal of T He R Emainder Is Al Ways Laid Down In

T H E S T O R Y O F G L A M O R G A N EVA N S J. C . T r o f u s e l y 3 l l u s t t a t c b 1 9 0 8 MP NY L M TED THE EDU C ATIONAL PUBLISHING C O A , I I C RD FF TRADE STREET . A I . PREFA C E. “ THE STORY o r GLAMORGAN is a modified f orm o f a z at t he Ro al Nat a Eisteddf o d o f Wa e pri e essay y ion l l s, “ 1 90 5 It has b ee t e-w te and ut in a M u tain . o n Ash , n rit n, p r scho o ls and the e e a ublic more readab le f orm f o g n r l p . — The b o ok deals with the county in districts chiefly districts — l y ing within t he several river b asins wit h f ur th er chapt ers and t ca f act Al l dealing wit h general geograp hical his ori l s . the more important towns and industrial centres have special de t e em chapt ers vo d t o t h . ‘ The b e t b o n G am a a e b ee c t e s ooks l org n h v n onsul d, and every care has b een t aken to ensure accuracy b ot h in t he inf ormat ion given and t he maps and plans t hat illustrat e the t x t The w t e e e des e t o ac w e e eat e . -

Council Summons

COUNCIL SUMMONS You are hereby summoned to attend a Meeting of the COUNCIL OF THE CITY AND COUNTY OF SWANSEA to be held in the Council Chamber, County Hall, Swansea on Thursday, 25th October 2007 at 4.00pm The following business is proposed to be transacted: Page No’s 1. Apologies for Absence. 2. To Receive Disclosures of Personal Interest from Members in accordance with the provisions of the Code of Conduct adopted by the City & County of Swansea. (NOTE: You are requested to identify the Agenda Item / Minute No. Planning Application No. and Subject Matter to which the interest relates). 3. To receive and sign as a correct record the Minutes of the following Council meetings : Council of 13th September 2007. 1-9 Extraordinary Council 4th October 2007. 10-17 4. Presiding Officer’s Announcements. 5. Leader’s Announcements. 6. Public Questions in accordance with Procedure Rule 16. Questions must relate to matters on the open part of the Agenda of the meeting and will be dealt within a ten minute period. 7. Public Presentations: (1) Swansea Credit Union - Loans and Savings Abertawe (LASA) 8. Cabinet Member Report(s) (A) Community Leadership & Democracy Portfolio (1) Membership of Committees. 18-19 (B) Environment Portfolio (1) Countryside Access Plan - Consultation. 20-50 (C) Housing Portfolio (1) Petition – Request for CCTV at Pantgwyn Sheltered Complex, Sketty. 51-53 (D) Finance Portfolio (1) Treasury Management Annual Report 2006/07. 54-67 (2) Asset Management Plan for Property Assets 2007/08. 68-69 (E) Top Performance and eGovernment Portfolio (1) Annual Improvement Plan - Stage 2. -

Environment Agency Rip House, Waterside Drive Aztec West Almondsbury Bristol, BS32 4UD

En v ir o n m e n t Agency ANNEX TO 'ACHIEVING THE QUALITY ’ Programme of Environmental Obligations Agreed by the Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions and for Wales for Individual Water Companies As financed by the Periodic Review of Water Company Price Limits 2000*2005 The Environment Agency Rip House, Waterside Drive Aztec West Almondsbury Bristol, BS32 4UD June 2000 ENVl RO N ME NT, AGEN CY 1 ]2 7 0 0 CONTENTS For each water and sewerage company' there are separate lists for continuous, intermittent discharges and water abstraction sites. 1. Anglian Water 2. Welsh Water 3. Northumbrian Water Group Pic 4. North West Water Pic 5. Severn Trent Pic 6. Southern Water Pic 7. South West Water Pic 8. Thames Water Pic 9. Wessex Water Pic 10. Yorkshire Water Pic 11. List of water abstraction sites for water supply only companies National Environment Programme Key E A R e g io n Water Company ID Effluent Type A A n g lia n . A Anglian Water SCE Sewage Crude Effluent M Midlands DC Dwr Cymru Welsh Water SSO Sewage Storm Overflows NE North East N Northumbrian Water STE Sewage Treated Effluent NW North W est NW North West Water CSO Combined Sewer Overflow S Southern ST Severn Trent Water EO Emergency Overflow SW South W est S Southern Water ST Storm Ta n k T Th a m e s sw South West Water . WA W ales T Thames Water Receiving Water Type wx Wessex Water C Coastal Y Yorkshire Water E Estuary G Groundwater D rive rs 1 Inland CM 3 CM 1 Urban Waste Water Treament Directive FF1 - 8 Freshwater Fisheries Directive Consent conditions/proposed requirements **!**!** GW Groundwater Directive Suspended solids/BOD/Ammonia SW 1 -12 Shellfish Water Directive NR Nutrient Removal S W A D 1 - 7 Surface Water Abstraction Directive P Phosphorus (mg/l) H A B 1 - 6 Habitats Directive N Nitrate (mg/i) B A T H 1 -1 3 Bathing Water Directive 2 y Secondary Treatment SSSI SSSI 3 y Tertiary Treatment QO(a) - QO(g) River and Estuarine Quality Objectives LOC Local priority schemes . -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses British carboniferous bryozoan biogeography Billing, Ian Michael How to cite: Billing, Ian Michael (1991) British carboniferous bryozoan biogeography, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6289/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk BRITISH CARBONIFEROUS BRYOZOAN BIOGEOGRAPHY Ian Michael Billing, B.A. The College of St. Hild & St. Bede A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Durham Department of Geological. Sciences, June, 1991 University of Durham. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. !(6~1.. - F~R)v~~iJf ~ 2 1 APR 1992 CONTENTS Contents List of figures v List of new and revised species lX Acknowledgements -

The Story of Glamorgan

, net THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES THE STORY OF GLAMORGAN. Count? Series BY C. J. EVANS "profusely "3llustrate6 1908 THE EDUCATIONAL PUBLISHING COMPANY, LIMITED TRADE STREET. CARDIFF. DA 74 O PREFACE. " " THE STORY OF GLAMORGAN is a modified form of a prize essay at the Royal National Eisteddfod of Wales, Mountain Ash, 1905. It has been re-written, and put in a more readable form for schools and the general public. The book deals with the county in districts chiefly districts lying within the several river basins with further chapters dealing with general geographical and historical facts. All the more important towns and industrial centres have special chapters devoted to them. The best books on Glamorgan have been consulted, and every care has been taken to ensure accuracy both in the information given and the maps and plans that illustrate the text. The writer here desires to acknowledge his great indebtedness to the works of previous writers on the subject. Thanks are also due for photographs lent by the Great Western and Messrs. Barry Railway Companies ; H. W. Wills, Cardiff; J. Storrie, Cardiff; Fred Evans, W. F. and Llangynwyd ; Dinsley, Manchester; D. Jones, Cymmer. The Publishers beg to announce that they have in the Press three booklets which will form valuable aids to this volume, viz. : 1. A Short Glossary of Glamorganshire Place Names. 2. Short Biographies of Glamorganshire Worthies. 3. School Journeys in Glamorgan. 880061 Vi. PREFACE The design on the cover will be new to most of our readers, and for it we are indebted to T. -

2015 Marine Mammal Strandings Annual Report

www.strandings.com Marine Mammal & Marine Turtle Strandings (Welsh Coast) Annual Report 2015 R.S.Penrose. July 2016 Marine Environmental Monitoring Penwalk Llechryd Cardigan Ceredigion West Wales SA43 2PS e-mail: [email protected] 1 CONTENTS Page 1 CRYNODEB GWEITHREDOL 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2 INTRODUCTION 6 3 MATERIALS AND METHODS 6 3.1 Live Animals. 7 3.2 Dead Animals. 7 4 RESULTS 8 4.1 Marine Mammals. 8 4.2 Bottlenose Dolphin Attacks. 13 4.3 Unusual Occurrences. 14 4.4 Live Strandings. 16 4.5 Tagging. 16 5 OTHER MARINE ANIMALS REPORTED TO THE NETWORK 17 5.1 Marine Turtles. 17 5.2 Seals. 18 5.3 Sharks. 19 6 SAMPLES 19 7 FUNDING 20 8 PUBLICITY 20 9 LEGISLATION 20 10 EQUIPMENT 21 11 TRAVEL 21 12 ADMINISTRATION 21 13 CAUSE OF DEATH 21 14 LIST OF SCIENTIFIC NAMES USED IN THIS REPORT 22 15 MATTERS ARISING 22 16 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 22 17 APPENDICES 22 2 List of Figures. page Figure 1. Current Technical Co-ordination of the Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme (CSIP). 6 Figure 2. Reported bottlenose dolphin strandings on the Welsh coast. 10 Figure 3. Bottlenose dolphin strandings by month. 10 Figure 4. Bottlenose dolphin strandings averaged over 1990 to 2015. 10 Figure 5. Reported harbour porpoise strandings on the Welsh coast. 11 Figure 6. Harbour porpoise strandings by month. 11 Figure 7. Harbour porpoise strandings averaged over 1990 to 2015. 11 Figure 8. Reported grey seal mortality on the Welsh coast. 12 Figure 9. Grey seal mortality by month. 12 Figure 10.