The Slow Death of the Carrier Air Wing Gary Wetzel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vs-38 Deactivated

Sea Control Squadrons Deactivated By LCdr. Rick Burgess, USN (Ret.) VS-29 Dragonfires ea Control Squadron (VS) 29 is scheduled for Hawk (CV 63) for its 1981 WESTPAC/Indian Ocean cruise. Sdeactivation on 30 April 2004, at NAS North Island, VS-29 was assigned with CVW-15 to Carl Vinson (CVN Calif., as one of the first VS squadrons to be disbanded in 70) in 1982 and in 1983 deployed to the Mediterranean and the drawdown of the S-3 Viking community. VS-29 will end on through the Indian and Pacific oceans to the ship’s new 43 years of service after a combat deployment in support of home port on the West Coast. Over the next seven years, Operation Iraqi Freedom. Cdr. Keff M. Carter will be the VS-29 completed four WESTPAC/Indian Ocean last CO of the Dragonfires. deployments on board Carl Vinson. The unit was established as a split-off of VS-21 as Air During these operations, the Dragonfires Antisubmarine Squadron 29 on 1 April 1960 at North operated near the Soviet Union and Island, its home base throughout its service. Equipped with also supported Operation Ernest S2F-1/1S (S-2A/B) Tracker antisubmarine warfare (ASW) Will, the escort of tankers in the aircraft, VS-29 joined Antisubmarine Carrier Air Group Arabian Gulf during the Iran-Iraq (CVSG) 53 assigned to Kearsarge (CVS 33). Except for a War. one-month exercise with CVSG-54 on board Wasp (CVS 18) in 1971, VS-29 remained with CVSG-53 until 1973. While assigned to Kearsarge, VS-29 participated in numerous exercises in the eastern and central Pacific. -

Col Charette Bio with Photo

Lunch Keynote Speaker 2010 Behavior, Energy & Climate Change Conference Colonel Bob Charette Jr. Director, Expeditionary Energy Office United States Marine Corps Colonel Bob “Brutus” Charette Jr. was born in Scranton, PA. He enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserves in 1985 and attended boot camp at Parris Island, SC. He then attended Officer Candidate School in Quantico, VA and was commissioned August 1986. He has earned a Bachelors of Science degree in Chemistry from Delaware Valley College (1986), Masters of Business Administration from the University of Phoenix (2002), and a Masters of National Security Strategy from the National War College (2007). Major professional schools attended; The Basic School (1986), Naval Fight Training (1988), FA-18 Flight Training (1989), Navy Fighter Weapons School (1991), Tactical Air Control Party School (1993), Weapons and Tactics Instructor course (1994), and Aviation Safety Officers course (1998), Army Command and General Staff College (2000- 2001), Marine Corps Commanders course (2004), and the National War College (2007). Units served and billets; VMFA-235 Embarkation and Pilot Training Officer (1989-1993), 3d Battalion/3d Marines Air Officer and Operations Officer (1993), VMFA-312 Admin Officer and Pilot Training Officer (1993-1995). VMFA-451 Aircraft Maintenance Officer and Operations Officer (1995- 1997), Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron-1 FA-18 Instructor, Director of Safety and Standardization, and Tactical Aircraft Department Head (1997-2000). I Marine Expeditionary Force G-5 CENTCOM Planner (2001), Task Force-58 Air Officer (2001-2002), VMFA-314 Executive Officer (2002- 2003), VMFA-323 Commanding Officer (2003-2005), Marine Aircraft Group-11 Operations Officer (2005- 2006). -

Conversations from Cecil Field, Florida

Conversations from Cecil Field, Florida TRANSCRIPTIONS OF ORAL HISTORY RECORDINGS OF NINETEEN WHO SERVED Lyn Corley Out in the piney woods of Northeast Florida was born NAAS Cecil Field, child of NAS Jacksonville. From two hangars, Hangar 13 and Hangar 14, and a 2,000-foot diameter circular landing mat it grew with the addition of four 5,000-foot runways. It grew to house a jet squadron in 1949 with Carrier Air Group 1 and Fleet Aircraft Service Squadron 9. It grew with four 8,000- foot runways to become the first Master Jet Base in the South. It grew to have eight hangars and 19,000 acres with its own outlying fields. Its extended 12,500-foot runway grew to become an alternate landing site for NASA space shuttles. It grew with the addition of Naval Weapons Station Yellow Water with over 10,000 acres, Outlying Field Whitehouse, and Pinecastle Bombing Range. Cecil grew to encompass 3% of the land area of Duval County, Florida. Cecil served our world by becoming a training base for those who would protect American lives and freedoms that we cherish. Tens of thousands of men and women came through its gate to serve. They lived and died in that pursuit. Cecil had promise “to continue to be a station of significant importance to readiness in the U. S. Atlantic fleet” according to public relations materials but, NAS Cecil Field passed away on September 30, 1999. Many fought to save its life and the City of Jacksonville, Florida and those who served there mourned its passing. -

Talent Management Analysis for the Air Wing of the Future

NPS-HR-20-024 ACQUISITION RESEARCH PROGRAM SPONSORED REPORT SERIES Talent Management Analysis for the Air Wing of the Future December 2019 LCDR Michael J. Bartolf, USN LCDR Louis D’Antonio, USN Thesis Advisors: William D. Hatch, Senior Lecturer Dr. Robert F. Mortlock, Professor Graduate School of Defense Management Naval Postgraduate School Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Prepared for the Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA 93943. Acquisition Research Program Graduate School of Defense Management Naval Postgraduate School The research presented in this report was supported by the Acquisition Research Program of the Graduate School of Defense Management at the Naval Postgraduate School. To request defense acquisition research, to become a research sponsor, or to print additional copies of reports, please contact the Acquisition Research Program (ARP) via email, [email protected] or at 831-656-3793. Acquisition Research Program Graduate School of Defense Management Naval Postgraduate School ABSTRACT The Air Wing of the Future (AWOTF) will provide unmatched lethality and capability in future theaters of operations. The addition of the F-35C Lightning II, MQ-25 Stingray, and CMV-22B to the combat proven team of F/A-18E/F Super Hornets, EA-18G Growlers, E-2D Hawkeyes, and MH-60R/S Seahawks also comes with increased manpower support requirements over today's carrier air wing. The increased complement of personnel necessary to operate the AWOTF will either require a multimillion-dollar ship modification to the baseline design, or a reduction to the individual squadron manpower documents. The objective of this capstone was to analyze manpower talent management, maintenance training, and squadron-level maintenance activities to determine whether a training improvement solution could substantiate a manpower reduction by creating a higher-quality, more capable work force. -

Lieutenant Commander Martin L

CAPTAIN JEFFREY J. CZEREWKO, USN Director OPNAV N2N6 F2, Battlespace Awareness Captain Czerewko, a native of Saginaw, Michigan, graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1990 with a degree in General Science and was designated a Naval Aviator in February of 1993. His operational assignments include the Sunday Punchers of Attack Squadron 75 (VA-75), the Sunliners of Strike Fighter Squadron 81 (VFA-81), the Knighthawks of Strike Fighter Squadron 136 (VFA- 136), and commanded both the Blue Diamonds of Strike Fighter Squadron 146 (VFA-146) and Carrier Air Wing TWO (CVW-2). He has completed six carrier deployments in USS ENTERPRISE (CVN- 65), USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER (CVN-69), USS JOHN F KENNEDY (CV-67), USS GEORGE WASHINGTON (CVN-73), USS JOHN C STENNIS (CVN-74) and USS RONALD REAGAN (CVN-76) accumulating more than 3,600 flight hours and 930 carrier arrested landings. His additional assignments include Assistant Safety and Assistant Training Officer at Strike Fighter Squadron 106 (VFA-106) as well as service with the Naval Special Warfare Development Group (DEVGRU) out of Dam Neck, VA. Captain Czerewko graduated from the National War College with a M.S. in National Security Strategy and served on the Joint Staff in the J-39 Deputy Directorate for Global Operations as an Information Operations Action Officer and the Electronic Warfare Branch Chief. He was also assigned as the Battle Captain at the Combined Air and Space Operations Center in Al Udeid, Qatar. He was twice awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Leadership Award and his personal decorations include the Legion of Merit, Defense Meritorious Service Medal (2), Meritorious Service Medal, Air Medal (3), Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal (3), Joint Commendation Medal, Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medal (4) and various campaign and service ribbons. -

WAR and PEACE in the HORNET Updated 0630/2016

WAR and PEACE in the HORNET Updated 0630/2016 The Fist’s “marriage” with the CORSAIR II lasted just 15 years before transitioning to the F/A-18 Hornet. The Marines fielded their first Hornet squadron, VMFA-314, in January 1983. Some six months later, VFA-113 and VFA-25 were the first customers at VFA-125, the West Coast Hornet training squadron. The Fists received their first Hornet on 11 November, an important date in Fist History, and reported to CVW-14 in January 1984. As of 2012, the squadron has flown the Hornet longer than any other assigned aircraft (only 21 years in the SPAD). Editor: The following chronology is incomplete in some periods, pending access to additional command reports. Inputs are welcome: [email protected] CHRONOLOGY 1983 Commander in Chief - Ronald Reagan. 1 January The Squadron’s 40th birthday. 1 January VA-25 began the year serving under the command of Captain D. W. Baird, Commander, Carrier Air Wing Two, and under the operational control of Commodore D. B. Cargill, Commander Light Attack Wing, U. S. Pacific Fleet. 7 January The first F/A-18 Hornets entered operational service with VMFA-314, replacing that squadron’s F-4 Phantom II aircraft. 25 April CDR Steve L. WEBB relieved CDR R. W. LEONE as Commanding Officer. 2 May Lt. Leslie Provow, assigned to VRC-40, became the first woman designated a Landing Signal Officer (LSO). 11 May Fist of the Fleet was awarded the LTJG Bruce Carrier Memorial Award for excellence in Maintenance for CY1982. May The squadron provided six aircraft and ten pilots in support of the F-15 Fighter weapons School at Nellis AFB. -

FEATURED SPEAKERS DAY 1 Vice Admiral Scott Stearney, Commander, Combined Maritime Forces Vice Adm

DAY ONE: 29 January 2019 OPERATIONAL PERSPECTIVES This Day will provide you with an analysis of current Day One will: operations, ranging from MIO, counter-narcotics, mine Improve your understanding of operational challenges and warfare and anti-piracy to peer-on-peer contest. Ways allow you to align your solutions to the requirements of key to enhance operational versatility and multi-mission NATO Navies modularity to retain combat superiority against the Help you enhance interoperability and integrate a common full spectrum of asymmetric and conventional threats naval architecture for multinational operations by listening to senior naval officers about best practices will be covered. Strategic leaders from NATO navies and Debate how to attain strategic maritime superiority for partners will examine distributed lethality, CONOPS, operations against low volume threats, such as illegal TTPs, interoperability, and situational awareness in fisheries, trafficking, piracy congested and degraded C2 operating environments. Given Provide feedback from current operations to refine your the increasingly inter-connected operating environment, CONOPS and TTPs for future conflict speakers will outline current and anticipated capability, as Enhance your understanding of ways to strengthen well as emerging requirements to retain the competitive maritime security in your area of responsibility and edge in multi-domain warfare. upgrade C2and ISR in congested environments FEATURED SPEAKERS DAY 1 Vice Admiral Scott Stearney, Commander, Combined Maritime Forces Vice Adm. Scott Stearney is a native of Chicago, Illinois. He graduated from the University of Notre Dame prior to commissioning in the U.S. Navy in 1982. He entered flight training and was designated a Naval Aviator in 1984. -

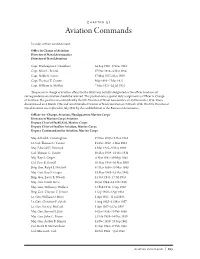

Aviation Commands

Chapter 21 Aviation Commands In order of their establishment: Office in Charge of Aviation Director of Naval Aeronautics Director of Naval Aviation Capt. Washington I. Chambers 26 Sep 1910–17 Dec 1913 Capt. Mark L. Bristol 17 Dec 1913–4 Mar 1916 Capt. Noble E. Irwin 17 May 1917–May 1919 Capt. Thomas T. Craven May 1919–7 Mar 1921 Capt. William A. Moffett 7 Mar 1921–26 Jul 1921 The person in charge of aviation affairs for the Navy was initially designated as the officer to whom all correspondence on aviation should be referred. This position was a special duty assignment as Officer in Charge of Aviation. The position was identified by the title Director of Naval Aeronautics on 23 November 1914. It was discontinued on 4 March 1916 and reinstituted as Director of Naval Aviation on 7 March 1918. The title Director of Naval Aviation was replaced in July 1921 by the establishment of the Bureau of Aeronautics. Officer–in–Charge, Aviation, Headquarters Marine Corps Director of Marine Corps Aviation Deputy Chief of Staff (Air), Marine Corps Deputy Chief of Staff for Aviation, Marine Corps Deputy Commandant for Aviation, Marine Corps Maj. Alfred A. Cunningham 17 Nov 1919–12 Dec 1920 Lt. Col. Thomas C. Turner 13 Dec 1920–2 Mar 1925 Maj. Edward H. Brainard 3 Mar 1925–9 May 1929 Col. Thomas C. Turner 10 May 1929–28 Oct 1931 Maj. Roy S. Geiger 6 Nov 1931–29 May 1935 Col. Ross E. Rowell 30 May 1935–10 Mar 1939 Brig. Gen. Ralph J. Mitchell 11 Mar 1939–29 Mar 1943 Maj. -

Natops Landing Signal Officer Manual

THE LANDING NAVAIR 00-80T-104 SIGNAL OFFICER THE LSO WORKSTATION NATOPS NORMAL LANDING SIGNAL PROCEDURES OFFICER MANUAL EMERGENCY PROCEDURES EXTREME WEATHER CONDITION OPERATIONS THIS PUBLICATION SUPERSEDES NAVAIR 00-80T-104 DATED 1 MAY 2007. COMMUNICATIONS NATOPS EVAL, PILOT PERFORMANCE RECS, A/C MISHAP STATEMENTS DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT C — Distribution authorized to U.S. Government Agencies and their contractors to protect publications required for official use or for administrative or operational purposes only, effective (01 May 2009). Other requests for the document shall be referred to COMNAVAIRSYSCOM, ATTN: NATOPS Officer, Code 4.0P, 22244 Cedar Point Rd, BLDG 460, Patuxent River, MD 20670−1163 DESTRUCTION NOTICE — For unclassified, limited documents, destroy by any method that will prevent disclosure of contents or reconstruction of the document. ISSUED BY AUTHORITY OF THE CHIEF OF NAVAL OPERATIONS AND UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE COMMANDER, NAVAL AIR SYSTEMS COMMAND. INDEX 0800LP1097834 1 (Reverse Blank) 1 MAY 2009 NAVAIR 00-80T-104 DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY NAVAL AIR SYSTEMS COMMAND RADM WILLIAM A. MOFFETT BUILDING 47123 BUSE ROAD, BLDG 2272 PATUXENT RIVER, MD 20670-1547 1 May 2009 LETTER OF PROMULGATION 1. The Naval Air Training and Operating Procedures Standardization (NATOPS) Program is a positive approach toward improving combat readiness and achieving a substantial reduction in the aircraft mishap rate. Standardization, based on professional knowledge and experience, provides the basis for development of an efficient and sound operational procedure. The standardization program is not planned to stifle individual initiative, but rather to aid the Commanding Officer in increasing the unit’s combat potential without reducing command prestige or responsibility. -

Not for Publication Until Released by the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Tactical Air and Land Forces Statemen

NOT FOR PUBLICATION UNTIL RELEASED BY THE HOUSE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE SUBCOMMITTEE ON TACTICAL AIR AND LAND FORCES STATEMENT OF THE HONORABLE JAMES F. GEURTS ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF THE NAVY RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT AND ACQUISITION ASN(RD&A) AND LIEUTENANT GENERAL STEVEN RUDDER DEPUTY COMMANDANT FOR AVIATION AND REAR ADMIRAL GREGORY HARRIS DIRECTOR AIR WARFARE BEFORE THE TACTICAL AIR AND LAND FORCES SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE HOUSE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE ON DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY AVIATION PROGRAMS March 10, 2020 NOT FOR PUBLICATION UNTIL RELEASED BY THE HOUSE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE SUBCOMMITTEE ON TACTICAL AIR AND LAND FORCES Introduction Chairman Norcross, Ranking Member Hartzler and distinguished members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to appear before you today to discuss the Department of the Navy’s (DoN) Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 budget request. We appreciate your leadership and steadfast support for Navy and Marine Corps aviation acquisition and research programs. Dominant naval force and a strong maritime strategy are the primary engines of our National Defense Strategy (NDS). As we continue to face rapid change in the global security environment, including greater global trade and greater unpredictability, our national security posture must likewise change to adapt to the emerging security environment with a sense of urgency and innovation. This requires the right balance of readiness, capability and capacity as well as budget stability and predictability. It necessitates us to deliver relevant, effective, capability to our Sailors and Marines, and a constant focus on and partnership with the industrial base. They are key elements to our national security. The character of war has changed, and so must our approach to developing the world’s most lethal military force. -

Regaining the High Ground at Sea Transforming the U.S

Regaining the High Ground at Sea Transforming the U.S. Navy’s Carrier Air Wing for Great Power Competition Study outline • Key operational challenges for naval forces • Naval strategy and posture • New carrier air wing operational concepts • Proposed aircraft and air wing composition • Recommendations and implementation Long-range sensors & weapons provide escalation dominance NOTE: Range arcs are illustrative Northern Military District of possible threats rather than an actual force laydown. SS-N-27A (500 km) Central Military District H-6K (1800 km) Western Military District OTH-R Receivers CJ-10 (2,200 km) Eastern Military District DF-11A/ CSS-7 Mod 1 OTH-R (350 km) Receiver Southern Military District DDG (3 days, 1200 km) OTH-R Receivers SS-N-22 (240 km) S-300PMU (90 km) S-300PMU1 (150 km) Oahu S-300PMU2/ HQ-9 (200 km) 7000 km S-400 (400 km) CONUS 7500+ km SSK (18 days, 1730 km) SS-N-27A (350km) 500 km Adversary able to mount attacks all along escalation ladder; U.S. and allies SSNneed (75 days, 3250 km) YJ-82 (33km) to be survivable and effective at various scales to provide options 3 Threat inside 1000 nm may prevent effective CVW or air base operations 200 nm 400 nm 600 nm 800 nm 1,000 nm 1,200 nm 1,400 nm 1,600 nm 1,800 nm 2,000 nm 2,200 nm 1 Day of PLAAF Air Raids Rocket Forces Conventional Missiles • 2 x JH-7A Fighter-Bomber Brigades (of 4 in PLAAF, Range Payload ASM 2,000 60/120 JH-7As as given in IISS) System Missiles Launchers (nm) (lbs) Variant? Assumptions: • Ranges measured from China coastline DF-11A 270 1,100 - ~890 108 • Assumes 4 hr turnaround time, 70% Ao, multiple crews DF-15B 430 1,100 Yes ~425 81 • Stairsteps represent switch to drop tanks • Constant rate of fuel burn assumed DF-16 540 ? - ~30 12 • No aerial refueling DF-21A 1,350 1,320 - 80 1,500 DF-21C 945 1,320 - ~300 36 DF-21D 1,080 1,320 Yes 18 DF-26 2,160 ? Yes ~30 16 DH-10 1,190 1,100 - ~375 54 Source: IHS Jane’s (range, payload, CEP, variants), IISS (launchers), missile inventories estimated using DoD and Jane's information. -

In Brief: the Logic of Aircraft Carrier Strike Groups

In Brief: The Logic of Aircraft Carrier Strike Groups This assessment provided the read-ahead for a recent carrier strike group working forum hosted by the Lexington Institute. Loren Thompson Lexington Institute September 2019 Global Trends Are Strengthening The Case For Carrier Strike Groups The United States is the only nation in history that has sustained a fleet of large-deck, nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. “Large-deck” means the carrier has over four acres of deck space, enough to support a carrier air wing of 75 or more aircraft. “Nuclear-powered” means the carrier has unlimited range and endurance, requiring refueling only once during its 50-year service life. Current law requires a fleet of at least 11 such carriers, enough to support forward deployment of three to four carriers in the seas around Eurasia at any given time, and more during crises. Carriers typically operate in “strike groups” of several warships, with the carrier providing most of the offensive punch while surface combatants and submarines provide defense against overhead, surface and undersea threats. Large-deck carriers of the Nimitz and Ford class can sustain more than a hundred aircraft sorties per day, surging to over twice that number in wartime. With each strike aircraft capable of accurately delivering multiple smart bombs per flight, a carrier air wing can disable or destroy hundreds of targets in a single day. The Ford class was designed to optimize the efficiency of the flight deck and is able to generate more flights per day than previous generations of aircraft carriers. This increased sortie generation rate is critical for success in a peer/near-peer competitor environment.