An Ordinary Tragedy.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SST Defies Industry, Defines New Music

Page 1 The San Diego Union-Tribune October 1, 1995 Sunday SST Defies Industry, Defines New Music By Daniel de Vise KNIGHT-RIDDER NEWSPAPERS DATELINE: LOS ALAMITOS, CALIF. Ten years ago, when SST Records spun at the creative center of rock music, founder Greg Ginn was living with six other people in a one-room rehearsal studio. SST music was whipping like a sonic cyclone through every college campus in the country. SST bands criss-crossed the nation, luring young people away from arenas and corporate rock like no other force since the dawn of punk. But Greg Ginn had no shower and no car. He lived on a few thousand dollars a year, and relied on public transportation. "The reality is not only different, it's extremely, shockingly different than what people imagine," Ginn said. "We basically had one place where we rehearsed and lived and worked." SST, based in the Los Angeles suburb of Los Alamitos, is the quintessential in- dependent record label. For 17 years it has existed squarely outside the corporate rock industry, releasing music and spoken-word performances by artists who are not much interested in making money. When an SST band grows restless for earnings or for broader success, it simply leaves the label. Founded in 1978 in Hermosa Beach, Calif., SST Records has arguably produced more great rock bands than any other label of its era. Black Flag, fast, loud and socially aware, was probably the world's first hardcore punk band. Sonic Youth, a blend of white noise and pop, is a contender for best alternative-rock band ever. -

Grant Hart – 'Hot Wax' (Condor/MVD) Grant Hart – 'Hot Wax' (Condor

Grant Hart – ‘Hot Wax’ (Condor/MVD) http://www.uberrock.co.uk/cd-reviews/31-november-cd/291-grant-hart-h... News CD Reviews Gig Reviews Hell's Gigs Interviews Featüres Retrö Röck Störe Förüm Cöntact News CD Reviews November CD Grant Hart – ‘Hot Wax’ (Condor/MVD) Grant Hart – ‘Hot Wax’ (Condor/MVD) CD Reviews Written by Johnny H Wednesday, 11 November 2009 17:16 Quick history lesson for you, Grant Hart was once drummer of legendary umlaut using punk/alternative rock legends Hüsker Dü. This band quite possibly single- handedly influenced more scenes in their recording history than any other band known to man thanks to their A Life In Music # 2 by Lord diverse musical outputs. Zion of SPiT LiKE THiS When you mention Hüsker Dü you have the extremes of SLUGFEST 2 – Alma US hardcore punk at one end of their influence to Street, Abertillery - 7th & Americana bands such as The Hold Steady at the other 8th August 2009 end of the spectrum Mott The Hoople - Monmouth, Blake Theatre - When Hüsker Dü split in 1987, Grant Hart took his next musical steps to being a guitarist and frontman through initially a series of solo EP's and then the 'Intolerance' album before his tenure 25/26th September 2009 with Nova Mob in the early to mid nineties. Since Nova Mob folded Grant has from time to time Rick Nielsen - Cheap Trick dallied with various solo musical outputs the last one being released in 1999. A Life In Music # 1 by Lord Zion of SPiT LiKE THiS History lesson over, 'Hot Wax' is the here and now and is nine tracks of diverse mind expanding pop rock that has the heavy musk scent of Sixties garage rock and psychedelia all over it. -

Von the Fall Bis Sonic Youth Und Zurück

Von The Fall bis Sonic Youth und zurück Menschen | Don’t get him wrong…: Mark E. Smith wurde nur 60 Jahre alt Mark E. Smith sah schrecklich blass aus in den vergangenen Jahren. Dabei wirkte er früher immer sophisticated wie ein spießiger Student. Sehr hübsch sozusagen. War aber ganz anders. Und er zeigte seine Band The Fall vor. Die soll im Lauf der Zeit mehr als vier Dutzend Bandmembers gehabt haben. Von TINA KAROLINA STAUNER Mastermind Mark E. Smith als Frontman führte sie alle vor. Haben alle, die wollten, gesehen und gehört. Nur wer halt. Und was halt. Post-Hardcore-Punk, Indie-Rock, Avantgarde-Pop. Independent-Zeug. Das jeder hörte. Und niemand. Und ein paar namhafte Leute, die ich namentlich kenne. Mark E. Smith lebte von 1957 bis 2018. Mark E. Smith und The Fall: proletarisches Selbstbewusstsein Ich hatte mit der bloßen Pop- und Rock-Szene und der Indie-Szene kaum etwas zu tun. Aber doch so einiges. Mehr als so einiges. Ich hörte nie einfach nur Musik. Anfangs habe ich auch Sonic Youth nur am Rande wahrgenommen. Doch einmal beobachtete ich ein Sonic Youth-Konzert. Nein, zweimal. Und vor über 20 Jahren im Vorprogramm kriegte ich unvermutet mit, wie Kurt Cobain auf seine E- Gitarre eindrosch. In solchen Konzerten traf man jedes Mal auch die Leute, die Dinosaur Jr. hörten. Diese komischen Indie-Leute, von denen dann wiederum einige ständig von The Fall sprachen. Auf The Fall einigten sich Individualisten und ein paar mehr. Dinosaur Jr. aber wussten alle. Nun lebt Mark E. Smith nicht mehr. Es ist zu spät für ihn. -

![[063N]⋙ Husker Du: the Story of the Noise-Pop Pioneers Who](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8976/063n-husker-du-the-story-of-the-noise-pop-pioneers-who-2218976.webp)

[063N]⋙ Husker Du: the Story of the Noise-Pop Pioneers Who

Husker Du: The Story of the Noise-Pop Pioneers Who Launched Modern Rock Andrew Earles Click here if your download doesn"t start automatically Husker Du: The Story of the Noise-Pop Pioneers Who Launched Modern Rock Andrew Earles Husker Du: The Story of the Noise-Pop Pioneers Who Launched Modern Rock Andrew Earles Bob Mould, Grant Hart, and Greg Norton formed Hüsker Dü in 1979 as a wildly cathartic outfit fueled by a cocktail of anger, volume, and velocity. Here's the first book to dissect the trio that countless critics and musicians have cited as one of the most influential bands of the 1980s. Author Andrew Earles examines how Hüsker Dü became the first hardcore band to marry pop melodies with psychedelic influences and ear-shattering volume. Readers witness the band create the untouchable noise-pop of LPs like New Day Rising, Flip Your Wig, and Candy Apple Grey, not to mention the sprawling double-length Zen Arcade. Few bands from the original American indie movement did more to inform the alternative rock styles that breached the mainstream in the 1990s. Hüsker Dü truly were visionaries. Download Husker Du: The Story of the Noise-Pop Pioneers Who ...pdf Read Online Husker Du: The Story of the Noise-Pop Pioneers W ...pdf Download and Read Free Online Husker Du: The Story of the Noise-Pop Pioneers Who Launched Modern Rock Andrew Earles From reader reviews: Elsie Port: Throughout other case, little men and women like to read book Husker Du: The Story of the Noise-Pop Pioneers Who Launched Modern Rock. -

D.A. Levy Lives Press, Pinsapo, Rhom- Bus Press, and Shivastan Celebrating Renegade Presses Press Authors and Music 16Th Annual from Craig Schenker

LOST & FOUND 2 PASSENGER PIGEON 3 PINSAPO 4 RHOMBUS PRESS 5 BOOG CITY SHIVASTAN PRESS 6 A COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER FROM A GROUP OF ARTISTS AND WRITERS BASED IN AND AROUND NEW YORK CITY’S EAST VILLAGE ISSUE 124 FREE Celebrate Five of the City’s Best Small Presses Inside in Their Own Words and Live Woodstock—Kathmandu Readings from Lost & Found, Passenger Pigeon d.a. levy lives Press, Pinsapo, Rhom- bus Press, and Shivastan celebrating renegade presses Press authors and music 16th Annual from Craig Schenker. NYC Small Presses Night Sidewalk Cafe Tues. Dec. 11, 6:00 p.m., $5 suggested 94 Avenue A (@ E. 6th St.) The East Village For information call 212-842-BOOG (2664) [email protected] 5:30 p.m. Book Fair @boogcity BOOG CITY 2 WWW.BOOGCITY.COM Passenger Pigeon Press is a an independent press started by artist Tammy Nguyen. We aim to address geopolitics, science, and identity through visual art and writing. Our plat- form houses Martha’s Quarterly, Collaborations, and Public Domain. Working with inno- vators across many disciplines, we try to bridge disparate worlds such as the realms of policy and poetry. We want to resurrect narratives that have been erased. We produce in pursuit of nuance. Martha’s Quarterly Issue 10 Winter 2018 BRUTE DIGNITY Philip Anderson and Téa Chai Beer Martha’s Quarterly is a quarterly subscription of four handmade artist books a year. Named after Martha, the last passenger pigeon of its species, this project is a resurrection of the extinct through the publishing of inconclusive and political works combining individuals of disparate thought. -

Atom and His Package Possibly the Smallest Band on the List, Atom & His

Atom and His Package Possibly the smallest band on the list, Atom & his Package consists of Adam Goren (Atom) and his package (a Yamaha music sequencer) make funny punk songs utilising many of of the package's hundreds of instruments about the metric system, the lead singer of Judas Priest and what Jewish people do on Christmas. Now moved on to other projects, Atom will remain the person who told the world Anarchy Means That I Litter, The Palestinians Are Not the Same Thing as the Rebel Alliance Jackass, and If You Own The Washington Redskins, You're a ****. Ghost Mice With only two members in this folk/punk band their voices and their music can be heard along with such pride. This band is one of the greatest to come out of the scene because of their abrasive acoustic style. The band consists of a male guitarist (I don't know his name) and Hannah who plays the violin. They are successful and very well should be because it's hard to 99 when you have such little to work with. This band is off Plan It X records and they put on a fantastic show. Not only is the band one of the leaders of the new genre called folk/punk but I'm sure there is going to be very big things to come from them and it will always be from the heart. Defiance, Ohio Defiance, Ohio are perhaps one of the most compassionate and energetic leaders of the "folk/punk" movement. Their clever lyrics accompanied by fast, melodic, acoustic guitars make them very enjoyable to listen to. -

Q&A: Grant Hart on His Double Album the Argument, Bob Mould's

Page 1 of 5 Blogs Search Village Voice Live Sporting Ooh Look a TOP Jarvis Cocker At Working Out Win Esperanza blog The Whitney With Lissy Trullie Spalding Tickets STORIES Interviews Most Popular Stories Q&A: Grant Hart On His Double Album The Viewed Argument , Bob Mould's Memoir, And The 100 & Single: Madonna's Chart Transformation Into A Conditions For A Hüsker Dü Reunion Classic-Rock Act Q&A: Gran By Brad Cohan Thu., Apr. 5 2012 at 6:00 AM Mould's Memoir, And The Categories: Brad Cohan , Grant Hart , Interviews Reunion A Brief Primer On Riff Raff, The (Really Good) Houston Like183 Send 22 0 • StumbleUpon Rapper Who Will Be • Submit The Velvet Underground Win Sound Of The City's Quintessential New York Musician Live: Andr http://blogs.villagevoice.com/music/2012/04/grant_hart_interview.php 4/9/2012 Page 2 of 5 As Grant Hart bravely dealt with a godawful fire that nearly gutted his boyhood home in his native South St. Paul last year, the drummer/guitarist and visual artist—formerly of American noise-pop legends Hüsker Dü—found an emotional outlet, positing his brilliant pop songsmithery towards arguably his most immense effort to date, the double-concept- LP sprawl of The Argument . Sound of the City Not many artists besides the intrepid Hart—who already has struck concept-album gold with the monumental opuses Zen Arcade (with the Hüskers) and Last Days of Pompeii (in his post-Hüsker outfit, Nova Mob)—would tackle 17th-century poet John Milton's epoch 1,549 people like Paradise Lost (which was originally published in ten books) and transform it into a galvanizing, theatrical 90-minute set. -

Grant Hart - Hot Wax (2009) | Music Is Amazing

Grant Hart - Hot Wax (2009) | Music Is Amazing http://music.is-amazing.com/2009/10/22/grant-hart-hot-wax-2009 About me Contact Exclusive Forum Top views SEA RCH Search MUSIC BLOG // Home › Grant Hart - Hot Wax (2009) LANGUAGE Grant Hart - Hot Wax (2009) ENGLISH Submitted by Паша on Thu, 22.10.2009 - 12:48 РУССКИЙ DEUTSCH or Subscribe by Email USER LOGIN Username or e-mail: * Password: * CREATE NEW ACCOUNT REQUEST NEW PASSWORD LOG IN USING OPENID ST YLE S Grant Hart , the former drummer and songwriter for indie pioneers Hüsker Dü , has been less prolific than 8-BIT Family Death, Plant Talks former bandmate/rival Bob Mouldin the 20 odd years since the band's breakup. Nonetheless, Hart still recorded ACOUSTIC Glastonbury, more 5 releases both as a solo artist and with his band Nova Mob to a modicum of indie success. Hart's been ALTERNATIVE METAL Empire Of The Sun’s member relatively quiet this decade, performing at a benefit concert for the late Soul Asylum bassist Karl Mueller, and ALTERNATIVE ROCK writing with Elton John working with Godspeed You! Black Emperor. AVANTGARDE Lil Wayne To Release ‘No This is Hart's sixth solo album, recorded in Minneapolis and Montreal. It includes contributions from BLACK METAL Ceilings’ On Halloween members of Godspeed You! Black Emperor, A Silver Mt. Zion, and Rank Strangers . CHAMBER POP On The Sublime “Reunion”, CLASSIC ROCK Nowell Family Not Too Happy Artist: COUNTRY About It Grant Hart DARK POP Death Row Records To Release Album: DARKWAVE Box Set Including Work From Hot Wax DEATH METAL Tupac, Snoop Dogg & Dr. -

See a Little Light: the Trail of Rage and Melody Free

FREE SEE A LITTLE LIGHT: THE TRAIL OF RAGE AND MELODY PDF Bob Mould | 420 pages | 14 Nov 2013 | Cleis Press | 9781573449700 | English | San Francisco, United States Bob Mould & Shepard Fairey | City Arts & Lectures It would be his last record as a Minnesota resident. If I've got a message for anybody I used to work with, I'll tell them to their face. I honestly don't have any bad feelings toward the people I used to work with. Mould and his baby blue at last summer's Rock the Garden. The record owes a Forest Lake music store a big thanks. Touring for the record was less than profitable. The cello parts on the album were played by Jane Scarpantoniwho had just performed on R. Welcome to Artcetera. Arts- and-entertainment writers and critics post movie news, concert updates, people items, video, photos and more. Share your views. Check it daily. Remain in the know. Home All Sections Search. Log In Welcome, User. Coronavirus Minneapolis St. Minnesota Gov. Emmer: GOP's chances in U. House depend on Trump. Parents of children separated at border can't be found. Two people wounded in downtown St. Paul in suspected drive-by shooting. People of Praise, Barrett's small faith community, has deep roots in Minnesota. Barrett was trustee at private school with See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody policies. Just in time for Halloween, stream the 7 scariest movies ever made. Giuliani See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody in hotel bedroom scene in new 'Borat' film. -

MATT CHAMBERLAIN He’S Moved from Texas to New York to Seattle and Now to L.A., Sometimes Following Employment and Sometimes Chasing His Muse

!.!-!:).'% 02/ 02):%0!#+!'% %&//*4$)".#&34*/'-6&/$&4t130500-4 7). &2/-0%!2, VALUED ATOVER *ANUARY 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE )®4,&3%®4 /"*-5)04& (3"/5)"35 5&.104 ""30/$0.&44 5*14'035*.&,&&1*/( :&"340'41*/ "/*."-4"4-&"%&34 4637*7"-,*5 /"7&/&,01&38&*4 .645)"7&4'035)&30"% J>;ED;;L;HO8E:OM7DJI C7JJ9>7C8;HB7?D !ND !$,%2 ")33/.%44% #!22).'4/. '!4:%. (%97!2$ -ODERN$RUMMERCOM +%,4.%2 2%)4:%,, 2),%9 3!.#(%: 3(!2/.% 7!2$ Volume 36, Number 1 • Cover photo by Alex Solca CONTENTS Alex Solca Paul La Raia 36 AARON COMESS It’s been twenty years since the Spin Doctors embedded them- selves in the recesses of our ears with hits like “Two Princes,” “Little Miss Can’t Be Wrong,” and “Jimmy Olsen’s Blues.” Turns out those gloriously grooving performances represent but one side of this well-traveled drummer’s career. by Robin Tolleson Ebet Roberts 48 MATT CHAMBERLAIN He’s moved from Texas to New York to Seattle and now to L.A., sometimes following employment and sometimes chasing his muse. With his technical abilities and artful aesthetic, however, the first-call drummer would probably have plenty of work even if he moved to the moon. by Michael Dawson 64 GRANT HART In the mid-’80s, Hüsker Dü fused hardcore punk with bittersweet pop, setting the table for an entire generation of angst-ridden alterna-rockers. Two decades on, the band’s drummer traces the trio’s profound path of influence. by David Jarnstrom 47 THE 2012 MD PRO PANEL This year the Pro Panel once again represents the remarkable scope and depth of modern drumming, from the absolute pinnacle of studio recording Matthias Ketz to the forefront of arena performance, from the most shredding metal to the cutting edge of jazz. -

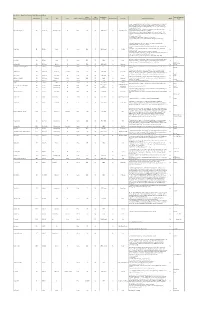

Extant Sites ‐ Properties Associated with Minneapolis Music

Extant Sites ‐ Properties Associated with Minneapolis Music Building Date Dates Used for Information Obtained Names Project Address Street Type Genres Extant | Demolished Still Music Related Current Use Notes from Various Sources Mapped Construction date Demolished Music From Originally located at 809 Aldrich Ave N, but that building was demolished in 1970 with I‐94 construction; new building at current location built. Place where Prince's parents, John Nelson and Mattie Shaw met while playing a concert. • 1301 10th Avenue North; Original house at 809 Aldrich Ave N • Started a new annual festival to replace the northside presence at the Aquatennial Phyllis Wheatley Center 1301 10th Ave N Community Center All Extant 1970 NA 1970‐Current Yes Community Center Parade which was contentious after the 1967 incident Yes o Northside Summer Fun Festival drew 6,000 people in its 6th year on August 9, 1978; performers included Sounds of Blackness, Flyte Tyme, Mind & Matter, Quiet Storm, and Prince o Prince also played in 1980 • Hosted Battle of the Bands concerts (no cash prize, just honor) • Original building built in 1924 as a settlement house; http://phylliswheatley.org/ Research • Music Notes Mural: Prince has famous picture in front of it from 1977 by Robert Whitman (book Prince Pre‐fame) 94 S 10th Street o http://www.hungertv.com/feature/the‐photographer‐behind‐princes‐first‐ever‐photo‐ shoot/ Music Notes 88 10th St S Mural All Extant 1908 NA 1971‐Current No The CPG o Painted in 1972 by owners of Schmidt Music (1908); Tom Schmitt great grandson of Yes company’s founder o Van Cliburn, one of world’s finest pianists, did photo session there http://minnesota.cbslocal.com/2014/03/30/finding‐minnesota‐the‐mystery‐musical‐mural/ o Featured in Time Magazine piece with Wendell Anderson o The notes are the third movement “Scarbo” in the piece “Gaspard de la Nuit” Research luxury hotel in 1926. -

HAS MOVED to the CINEMA THEATRE in GOLETA

2A Thursday, November 21,1986 Daily Nexus for a future, “ someone to believe in,” for “ love ... hope ... strength ... someone to live for.” He sings of Add the glowing touch to Alarminy §tren9^ being “ a lonely man walking lonely streets” and of the unease he feels when he steps out into the w orld. His Thanksgiving. Day the Raven left the Tower and concerns are not too off-base — in W alk Forever By My Side — they fa c t, he is righ t on ta rget. P e te rs has are the epitomy of a refined Alarm. the strength to sin g o f weakness — a The tunes are ballads — slow, hard song to sing — especially in comforting, oozing with sincerity. such upwardly mobile times when The acoustic guitar blues coupled men and women are cast as Send the with tender lyrics and Mike Peters’ superpeople and society has no hometown whining, pleading voice patience for the confused or the Harvest Glow create a pair of lullaby tunes surely weak. He rejects the plastic heroes Bouquet or to charm the heart. It’s quite a and the “ cruel world that kicks a change from the banner-waving, man when he’s down.” And he any other revolution-seeking rebels who confesses the unthinkable in our day sounded-off so desperately in The of independence: “ For I alone can’t warm flower Declaration. face the future/I need your But don’t worry. There has not strength/ To help me make it arrangement... The Alarm — Strength been a loss of Alarm energy.