Positions, and Serve but to Mislead Those Who, Ill Search of Such Information, Should Draw Conclusions from Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Perspectives in Australian Archaeology, Part VII. Aboriginal

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Robertson, Gail, 2011. Changing perspectives in Australian archaeology, part VII. Aboriginal use of backed artefacts at Lapstone Creek rock-shelter, New South Wales: an integrated residue and use-wear analysis. Technical Reports of the Australian Museum, Online 23(7): 83–101. doi:10.3853/j.1835-4211.23.2011.1572 ISSN 1835-4211 (online) Published online by the Australian Museum, Sydney nature culture discover Australian Museum science is freely accessible online at http://publications.australianmuseum.net.au 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia Changing Perspectives in Australian Archaeology edited by Jim Specht and Robin Torrence photo by carl bento · 2009 Papers in Honour of Val Attenbrow Technical Reports of the Australian Museum, Online 23 (2011) ISSN 1835-4211 Changing Perspectives in Australian Archaeology edited by Jim Specht and Robin Torrence Specht & Torrence Preface ........................................................................ 1 I White Regional archaeology in Australia ............................... 3 II Sullivan, Hughes & Barham Abydos Plains—equivocal archaeology ........................ 7 III Irish Hidden in plain view ................................................ 31 IV Douglass & Holdaway Quantifying cortex proportions ................................ 45 V Frankel & Stern Stone artefact production and use ............................. 59 VI Hiscock Point production at Jimede 2 .................................... 73 VII Robertson Backed artefacts Lapstone -

Ucp013-012.Pdf

INDEX* Titles of papers in bold face. Achomawi, 264, 267, 268, 283, £92, Arrow release, 120-122, 272, 334, 388. 293, 296, 299, 301, 314, 315, 320; Arrows and bullets, comparison, 373. basketry, 272. Aselepias, 281. Achomawi language, radical elements, Ash, used for bows, 106. 3-16; verb stems, secondary, 18; Astronomy, 323. suffixes, local, 19-21; pronouns, Athabascan groups, 313, 319, 326; 25-26; phonology, 28-33. bow, 336. Acknowledgments, 69. Atsugewi, 268, 293. Acorns, storage of, 282. Atsugewi language, radical elements, lAdiantum, in basketry, 273. 3-16; suffixes, local, 20; other Adolescence ceremony, girls', 306, verb and noun suffixes, 23; phon- 311-313, 314. ology, 28-33. boys', 314. Badminton, 350, 351, 355, 357, 358. African bow, 343, 384. Balsa (tule balsa, rush raft), 267, Alaskan bow, 338, 380. 268-269. Alcatraz island, 50. Bannerman, Francis, 350. Algonkin groups, 326. Barnes, bow maker, 356. Amelanchier alnifolia (serviceberry), Barton, R. F., 390. 361. Basket, "canoe," 250; as granary, Andaman islands, bow, 343, 384. 282-283. Anderson, R. A., quoted, 42, 44, 45, Basketry, complexes, 272; character- 47, 52-53. istics of, among the tribal groups, Apache bow, 340, 382; arrow, 382. 272-275; materials and tech- Apocynum cannabinum, 281. niques, 273-275; types: bottle- Archery, rounds in: English or York, neck, 273; coiled, 250, 263, 273, 123; American, 123; English, 332, 274; twined, 263, 272-273. See 351. also under names of tribes. Archery, Yahi, 104. Basketry cap, woman 's, 262-263; cap Armor, 299, 357. and hopper, 273; leggings, 262; Arrowheads, plates showing, opp. 103, moccasin, 262; traps, 248. -

Wintjer and SUMMER ANCE SERIES'

:t WINNTjER AND SUMMER ANCE SERIES' IN ZUF4 I",N 1918: By .,,,ELSIE CLEWS PARSONS UNIVIERSITY OF CALFORNA PUB-iCATIONS ZIs AMPRI(AI LARcTiAEOLOGY AND.E"NOLOGY. VOl 17, No. 3; PP. 171-216 E; r ,7,N UNIVERSITY ,OF CA4.AFORN1A,PE ;ER CALIFORNIA UN-VERSITY OF CALIFGORNA PUBLICATIONS TDEP.ARTENT- OP ANTHROPOLOGY - e following publica1iiona dealingwitSh&rchaeogical and etbllIogical subjcssed : nder the direition of-th Department of Athrpoogyare sen ii ech;ang fobhes publ- cations of anth log'cal 0daents and museus, add. for jouraLs &evoed to general anthropology or to archaolog edetiology. They arek for sale at the prices ttaed.- .Exchan.ges should be'lrectd to The Ebha4ge Deptn U ty ibry, Berleley eCalifia, U. S. A. All eorderssand rextances sould be addessed to the Universi of califoa Press." AM RICAN ARCHAZOLOGY A"P ETHNOLOGY.-A,'. E:iober, -Editr. PriCS :-Volume ll, $4.25; Volumes 2 -ot11, Inclusive :$3.50 eacb; Volue :12 ad followin,- $5.00 each. Ci-Oted.- aF---Unbiv. L tPubL Am.-Arch- Ethn : , e VoL 1. i. Life and- & u1re of t Hupa, by P3?ny arle Goddr. Pp. 1%8, plates 19031I30.Sepe _.. ....... .......... ....$1.2 >f2. UipaWexta by Pliny Eazle Goddd.. Pp. 89-368. March, 1904 ,....- . 3.00 Index, pp. 369478. 0 - VoL 2. 1. The Exploration of the Potter Crtek Cave, by William J. Sinclair. P. --..2--; plates 1-14. April, 1904Ar -- .40 2. The Languages of the oastof CAliforni South o-a Fnc1isc0o by A. L. Kroeborer. Pply.,29-8- wth a map. June, 1904 .. ..... so 3.' typesof Indian cult1*6in orni, by A. -

Lee's Precast Concrete Inc

MAY/JUNE 2014 A Publication of the National Precast Concrete Association precast.org LEE’S PRECAST CONCRETE INC. BUILDING CHARACTER Also in this issue: Portland Limestone Cement – Good for the Planet, Good for the Wallet Crane Training Requirements Changing for Precasters Damp Proofing vs. Waterproofing – Part 2 Find and Retain Quality Workers Insights Running on Fumes BY BRENT DEZEMBER | Chairman, National Precast Concrete Association f you’ve been following the construction the issue. Increasing the tax in an election year is industry news, you are no doubt aware that pretty much a non-starter, so that’s not likely to I the Highway Trust Fund is going broke. If happen. Simply transferring money into the trust you supply products to DOTs, this issue could fund is a Band-Aid approach that has been used potentially hit you right in the pocketbook. before, but it only delays the inevitable insolvency At the risk of Originally created to fund the construction of the discussion for a short-term period. We need a long- oversimplifying interstate highway system, the Highway Trust term approach. the issue, less Fund remains the backbone of the nation’s surface So let’s fix it. There are hopeful signs that maybe gas consumed transportation system. The fund gets its money this time we can get it done. Bill Shuster, the means less from a federal fuel tax of 18.3 cents per gallon of new chairman of the House Transportation and funding, and on gasoline and 24.4 cents per gallon of diesel fuel Infrastructure Committee, has floated the idea a national scale and related excise taxes. -

Terra Australis 30

terra australis 30 Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. Since the beginning of the series, the basic colour on the spine and cover has distinguished the regional distribution of topics as follows: ochre for Australia, green for New Guinea, red for South-East Asia and blue for the Pacific Islands. From 2001, issues with a gold spine will include conference proceedings, edited papers and monographs which in topic or desired format do not fit easily within the original arrangements. All volumes are numbered within the same series. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: Coastal Sites in Southern New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: Archaeological Excavations in the Eastern Central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: The Geography and Ecology of Traffic in the Interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: Art and Archaeology in the Laura Area. A. Rosenfeld, D. Horton and J. Winter (1981) Volume 7: The Alligator Rivers: Prehistory and Ecology in Western Arnhem Land. -

Survival Hacks

SURVIVAL HACKS OVER 200 WAYS TO USE EVERYDAY ITEMS FOR WILDERNESS SURVIVAL CREEK STEWART, author of Build the Perfect Bug Out Bag AVON, MASSACHUSETTS Contents Introduction CHAPTER 1 Shelter Hacks CHAPTER 2 Water Hacks CHAPTER 3 Fire Hacks CHAPTER 4 Food Hacks CHAPTER 5 Staying Healthy CHAPTER 6 Gear Hacks CHAPTER 7 Forward Movement CHAPTER 8 Everyday Carry (EDC) Kits on a Budget Conclusion Acknowledgments Introduction sur-VIV-al HACK-ing verb The act of using what you have to get what you need to stay alive in any situation. “Hacking” is making do with what you’ve got. It has three aspects: 1. Using knowledge of basic survival principles 2. Innovative thinking 3. Exploiting available resources KNOWLEDGE OF BASIC SURVIVAL PRINCIPLES Knowledge is the basis for almost every successful survival skill. You can get it from reading books, listening to the advice and stories of others, and watching the actions of others. However, the most important way to gain true knowledge of survival principles is trial and error with your own two hands. No method of learning takes the place of hands-on, personal experience. Your options in a survival scenario will ultimately depend on your understanding of basic survival principles that surround shelter, water, fire, and food. INNOVATIVE THINKING I’ve often said that innovation is the most important survival skill. Innovation can be defined in survival as creatively using available resources to execute a plan formulated using pre-existing survival knowledge. At the end of the day, the application of survival principles is only limited by your ability to creatively use them. -

Continuity and Change in Puebloan Ritual Practice: 3,800 Years of Shrine Use in the North American Southwest Phil R

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Anthropology Faculty Publications Anthropology, Department of Spring 3-2017 Continuity and Change in Puebloan Ritual Practice: 3,800 Years of Shrine Use in the North American Southwest Phil R. Geib University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Carrie Heitman University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Ronald C.D. Fields University of New Mexico - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/anthropologyfacpub Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Geib, Phil R.; Heitman, Carrie; and Fields, Ronald C.D., "Continuity and Change in Puebloan Ritual Practice: 3,800 Years of Shrine Use in the North American Southwest" (2017). Anthropology Faculty Publications. 137. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/anthropologyfacpub/137 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN PUEBLOAN RITUAL PRACTICE: 3,800 YEARS OF SHRINE USE IN THE NORTH AMERICAN SOUTHWEST Phil R. Geib, Carrie C. Heitman, and Ronald C.D. Fields Radiocarbon dates on artifacts from a Puebloan shrine in New Mexico reveal a persistence in ritual practice for some 3,800 years. The dates indicate that the shrine had become an important location for ceremonial observances related to warfare by almost 2000 cal. B.C., coinciding with the time when food production was first practiced in the Southwest. The shrine exhibits continuity of ritual behavior, something that Puebloans may find unsurprising, but also changes in the artifacts deposited that indicate new technology, transformations of belief, and perhaps shifting cultural boundaries. -

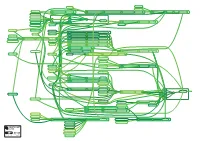

A1128 Able to Light a Fire Map of Influence

11591: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A LIMPET SHELL 12278: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A SAW 12113: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A MUSSEL SHELL 09112: A HUMAN BEING CUSTOMER 09475: A HUMAN BEING IN 12729: A HUMAN BEING IN 12281: A HUMAN BEING IN OF WH SMITH OR OR AND OR OR POSSESSION OF A ELASTIC BAND POSSESSION OF A WOOD WASHER AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE BOW DRILL FIRE LIGHTER 10630: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF CHERRY TREE OUTER BARK 12394: A HUMAN BEING IN OR POSSESSION OF A RIBWORT PLANTAIN PLANT LEAF 11946: A HUMAN BEING IN OR AND OR POSSESSION OF STINGING NETTLE PLANT BARK 09477: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF CORDAGE 11550: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR 10437: A HUMAN BEING IN OR AND POSSESSION OF A BOW POSSESSION OF WHITE WILLOW TREE INNER BARK 13740: A HUMAN BEING IN 00924: A HUMAN BEING USER 10197: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF SKIN BUYER OF TRADE-IT POSSESSION OF SWEET CHESNUT TREE INNER BARK 10607: A HUMAN BEING IN 10086: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF RASPBERRY PLANT BARK POSSESSION OF ASH TREE WOOD 09148: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF AN OPTICAL LENS 09472: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR POSSESSION OF A SUNLIGHT FIRE LIGHTER 09149: A HUMAN BEING LOCATED 01552: A HUMAN BEING IN IN DIRECT SUNLIGHT POSSESSION OF A KNIFE 09471: A HUMAN BEING IN 09720: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE DRILL FIRE POSSESSION OF LIME TREE WOOD LIGHTER 09479: A HUMAN BEING IN 10314: A HUMAN BEING IN 09965: A HUMAN BEING IN OR OR AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE PLOUGH FIRE POSSESSION OF HAWTHORN TREE WOOD POSSESSION OF A WOOD ROD LIGHTER 10182: -

Levels and Standards Boreal Wilderness Guide

Levels and Competences Level 1: Front Country General Standards Wilderness Guide Boreal-Nemoral Forest Level 2: Back Country Level 3: Expert Guide 1 2019 Raoul Kluivers (Voshaar Outdoor & Education) David Holder (Mahikan Trails) Skills and knowledge standards 2 Level 1 – Front Country General Level 1 standards At least 28 days (224 hours, counting 8 hours a day) of training At least two specializations A minimum of 28 days of (assistant) guiding Theory assignments: - Theory testing of the various subjects at the end of the academic year - Preparing a Wilderness related project (multiple days) including Risk and Emergency plan Skills and Knowledge standards Nature & Wildlife - Basic knowledge of tracks, animal gaits and patterns - Be able to use a field guide…fast. - Have proper knowledge about the flora and fauna of the area you are guiding in 2019 Raoul Kluivers (Voshaar Outdoor & Education) David Holder (Mahikan Trails) Hike & Survival - Use of Compass - Use of protractor - Use of GPS - Use of different scaled maps - Knowledge of the different Grid systems - Route-finding - Knife craft - Axe craft - Saw craft - Starting a fire with matches and lighter - Starting a fire with Flint & Steel - Starting a fire using what you have on you - Starting a fire using different types of natural kindling - Cotton and Vaseline as a Firestarter - Feather stick - Emergency shelter - Different ways to use a tarp 3 - Lean-to - Outdoor cooking using cast iron , campfire and stoves - Knowledge of at least 20 knots, 4 lashings, river cross system and 2 pully -

Northern Bushcraft (Mors Kochanski)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The greatest influence on my career as a student, instruc- tor and writer about wilderness living skills and survival, has been without question, Tom Roycraft of Hinton, whose many years of experience and incisive insights have lent considerable force to my bush knowledge. Another important person is Don Bright of Edson, with whom I published the W!derriess Arts and Recreation magazine. The magazine motivated me to produce a work- ing volume of written material that forms the basis for this and future books. I am grateful to the publisher Grant Kennedy, who pro- vided the encouragement that resulted in this book becom- ing available now rather than ten years from now. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 9 CHAPTER 1 FIRECRAFT 11 Fire-Lighting 12 Ignition 13 Establishment 28 Applications 38 Maintenance and Moderation 43 Choosing a Safe Fire Site 45 Methods of Suspending Pots 50 Outdoors Cooking 59 CHAPTER 2 AXECRAFT 71 The Bush Axe 71 Tree Felling 90 CHAPTER 3 KNIFECRAFT 109 The Bush Knife 109 CHAPTER 4 SAWCRAFT 135 The Saw and Axe 135 CHAPTER 5 BINDCRAFT 145 Cordage Techniques 145 CHAPTER 6 SHELTERCRAFT 157 Shelter Concepts 157 CHAPTER 7 THE DIRCHES 191 The Paper Birch 191 The Alders 211 CHAPTER 8 THE CONIFERS 213 White Spruce 213 Black Spruce 216 Tamarack 224 Jack and Lodgepole Pine 225 Balsam and Subalpine Fir 229 CHAPTER 9 THE WILLOWS 231 The Poplars 231 Quaking Aspen 232 Black Poplar 236 The Willows 239 CHAPTER 10 THE SHRUBS 243 Silver Willow 243 The Saskatoon 245 Red Osier Dogwood 245 The Ribbed Basket Forms 247 CHAPTER 11 THE MOOSE 251 The Majestic Beast 251 CHAPTER 12 THE VARYING HARE 269 The Key Provider 269 AUTHOR 282 INDEX 284 INTRODUCTION There is no reason why a person cannot live comfortably in the Northern Forests with a few simple, well-chosen possessions such as a pot and an axe. -

Residue and Use‐Wear Analysis of Non‐Backed

<PE-AT>Residue and use-wear analysis oF non-backed RETOUCHED ARTEFACTS FROM Deep Creek Shelter, SYDNEY BASIN: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE ROLE OF BACKED ARTEFACTS. Robertson, Gail; University of Queensland, Archaeology Attenbrow, Val; Australian Museum, ; University of Sydney, Archaeology Hiscock, Peter; University of Sydney, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Abstract A previous use-wear and residue analysis of backed artefacts from Deep Creek Shelter showed they had a range of functions and had been used with a variety of raw materials. Were non-backed retouched flakes at Deep Creek were used for different purposes? To answer this question, 40 non- backed specimens were selected for microscopic use-wear and residue analysis. Not all of these non- backed artefacts had been used, but we identified that many were scrapers, knives, incisors and saws. These tools were used for bone-working and wood-working, and possibly skin-working and non- woody plant-processing. Some of these non-backed retouched artefacts were hafted. For the first time, these results allow comparison of the tool use of backed and non-backed artefacts in Australia. At Deep Creek, the range of functions for the non-backed component was extremely similar to that of the backed artefacts. Although both artefact categories displayed similar tool use, they are distinguished in one interesting way: non-backed specimens were often single purpose, dedicated to one function, whereas backed artefacts were often multifunctional and multipurpose. These results help us understand the structure of tool use in Australia. Une analyse précédente de l'usure et des résidus d'artefacts sauvegardés de Deep Creek Shelter a montré qu'ils avaient une série de fonctions et avaient été utilisés avec une variété de matières premières. -

Survival Knife Guide-EN

Best Features of Survival Knife It’s about WHEN, not IF. All survival trainers and experts around the world agree on the need for a good survival knife. Some experts even say “A good survival knife is the thin line between life/death “. Although the best survival situation is the one you should avoid getting into, being prepared for it when you are going camping, hiking etc. is crucial. The term `survival knife` defines the purpose of the knife, means you will rely on the knife to save your life. Survival needs may occur in, wilderness, jungle, mountain, desert, urban, disaster, sea, combat situations. Hence a `survival knife` needs to be durable, practical and serve as a tool for many survival related needs; - Cutting / Piercing - Splitting / Carving - Digging - Shelter building - Fire starting - Food preparation - Hammering / Prying - First aid - Self-defense - Hunting Must Have Features of a ‘Survival Knife’ 1- Fixed Blade It goes without saying that a ‘Survival Knife’ must be a fixed blade. Although a folding blade has its’ uses, when it comes to reliability, the blade must be strong and not have weak spots. Even the best folding mechanisms can fail under extreme pressure, and you would not only hurt yourself, like cutting your hands/fingers, but also risk losing your most reliable survival tool. You cannot put straight down pressure to the tip of a folding blade as well, hence cannot use to pierce. 2- Full Tang & Flat Pommel Full Tang means that the blade extends from tip of the blade to the bottom as a single piece metal.