AFH-Dissertation Last Edits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music As Rhetoric in Social Movements

IRA-International Journal of Management & Social Sciences ISSN 2455-2267; Vol.09, Issue 02 (November 2017) Pg. no. 71-85 Institute of Research Advances http://research-advances.org/index.php/RAJMSS 1968: Music as Rhetoric in Social Movements Mark Goodman1#, Stephen Brandon2 & Melody Fisher3 1Professor, Department of Communication, Mississippi State University, United States. 2Instructor, Department of English, Mississippi State University, United States. 3Assistant Professor, Department of Communication, Mississippi State University, United States. #corresponding author. Type of Review: Peer Reviewed. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21013/jmss.v9.v2.p4 How to cite this paper: Goodman, M., Brandon, S., Fisher, M. (2017). 1968: Music as Rhetoric in Social Movements. IRA- International Journal of Management & Social Sciences (ISSN 2455-2267), 9(2), 71-85. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.21013/jmss.v9.n2.p4 © Institute of Research Advances. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License subject to proper citation to the publication source of the work. Disclaimer: The scholarly papers as reviewed and published by the Institute of Research Advances (IRA) are the views and opinions of their respective authors and are not the views or opinions of the IRA. The IRA disclaims of any harm or loss caused due to the published content to any party. Institute of Research Advances is an institutional publisher member of Publishers Inter Linking Association Inc. (PILA-CrossRef), USA. The institute is an institutional signatory to the Budapest Open Access Initiative, Hungary advocating the open access of scientific and scholarly knowledge. The Institute is a registered content provider under Open Access Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH). -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

Presumption of Innocence: Procedural Rights in Criminal Proceedings Social Fieldwork Research (FRANET)

Presumption of Innocence: procedural rights in criminal proceedings Social Fieldwork Research (FRANET) Country: GERMANY Contractor’s name: Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte e.V. Authors: Thorben Bredow, Lisa Fischer Reviewer: Petra Follmar-Otto Date: 27 May 2020 (Revised version: 20 August 2020; second revision: 28 August 2020) DISCLAIMER: This document was commissioned under contract as background material for a comparative analysis by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) for the project ‘Presumption of Innocence’. The information and views contained in the document do not necessarily reflect the views or the official position of the FRA. The document is made publicly available for transparency and information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or legal opinion. Table of Contents PART A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 1 PART B. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 4 B.1 PREPARATION OF FIELDWORK ........................................................................................... 4 B.2 IDENTIFICATION AND RECRUITMENT OF PARTICIPANTS ................................................... 4 B.3 SAMPLE AND DESCRIPTION OF FIELDWORK ...................................................................... 5 B.4 DATA ANALYSIS ................................................................................................................. -

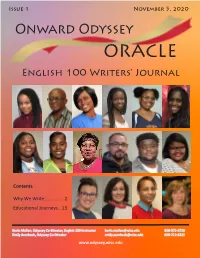

November 2020: Alumni English 100 Class Oracle

Issue 1 November 5, 2020 Onward Odyssey ORACLE English 100 Writers’ Journal Contents Why We Write .............. 2 Educational Journeys .. 13 Kevin Mullen, Odyssey Co-Director, English 100 Instructor [email protected] 608-572-6730 Emily Auerbach, Odyssey Co-Director [email protected] 608-712-6321 www.odyssey.wisc.edu Odyssey Oracle 11-5-2020 Why We Write If I had a chance to really look back wanted and not worry about the backlash. I could at my life, I can say that writing explore my feelings with words instead of keeping saved it. From the early years of them bottled up. It didn’t take me long to fill my me writing love letters to the guys journal up after figuring out that I had something who probably didn’t know I existed to say. I started to use my subject journals to jot to writing papers and poetry for down things in school, at family events, and even my Odyssey class, putting a pen to in church. It turned out that I did have something paper gave me the space to express myself freely to say! Instead of holding on to the mean things I and unafraid. I knew that my silent power could thought about myself at the time, I got them out. I take me into a world where what I said mattered was able to clear my mind while giving it space to and was appreciated. recreate how I felt about myself. In other words, I’d struck gold. Outside of my notebooks I was a gentle giant. -

Top Women Business Owners 34 Top Estate Planning Attorneys DEPARTMENTS & COLUMNS

St. Louis’ Best M&A Providers TheThe GuideGuide ToTo FindingFinding CapitalCapital InIn 20172017 SmallSmall How To Place Your Bets In An Uncertain World ST.ST. LOUIS LOUIS St.St. Louis’Louis’ BestBest inin QualityQuality BusinessBusiness Meet The Area’s Top Estate Planning Providers SBM MonthlyMonthly MeetMeet STL’sSTL’s MostMost AdmiredAdmired BusinessBusiness LeadersLeaders SBM JANUARYMARCH 2019 2017 TheThe SourceSource forfor BusinessBusiness OwnersOwners JANUARY 2017 St. Louis’THETHE TOOOP NESNESWOMEN BUSINTOTOESS OWNERS LearnWATCHWATCH What It TookFourFour To EntrepreneurialEntrepreneurial Build FirmsFirms Their PoisedPoisedCompanies forfor GreatnessGreatness LearnLearn howhow ZachZach Winkler’sWinkler’s appapp isis goinggoing toto makemake thethe worldworld aa safersafer placeplace You’re Invited: The Biggest Business Event Of The Year ST. LOUIS BUSINESS EXPO & BUSINESS GROWTH CONFERENCE, April 23, 2019 BOOTHS AVAILABLE Reserve your space 314.569.0076 www.stlexpo.com CYBER SECURITY THREATS ARE INCREASING NTP offers a broad range of solutions to AI advances allow for help your organization monitor, defend, more sophisticated attacks 80% of attacks exploit and respond to today’s continually known vulnerabilities evolving cyber threats. Global ransomware campaigns are spreading ARGISS INFERNO Hacking is more 317 million new pieces of sophisticated and evolving malware were created in 2017 Proactively Manage & Minimize Risk! Phishing attacks are 24/7 Monitoring & Rapid on the rise Response Team! Contact NTP at 636-458-4995 or online at NTPCyberSecurity.com for a complimentary Cyber Security Needs Analysis! Bring your Corporate meetings & Events to the NEXT LEVEL ϭϱϰ͕ϬϬϬƐƋ͘Ō͘ŽĨŇĞdžŝďůĞƐƉĂĐĞ ƵƚŽŵŝnjĞĚŝŶͲŚŽƵƐĞĐĂƚĞƌŝŶŐ ƩĂĐŚĞĚϮϵϲƌŽŽŵ͕ĨƵůůͲƐĞƌǀŝĐĞŚŽƚĞů :ƵƐƚϭϬŵŝŶƐ͘ĨƌŽŵ>ĂŵďĞƌƚͲ^ƚ͘>ŽƵŝƐ/ŶƚĞƌŶĂƟŽŶĂůŝƌƉŽƌƚ Call Julie to book your next event! 636.669.3021 You’ve been taking care of business. -

Marzo 2016 CULTURA BLUES. LA REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA Página | 1

Número 58 - marzo 2016 CULTURA BLUES. LA REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA Página | 1 Contenido Directorio PORTADA El blues de los Rolling Stones (1) …………………………...... 1 Cultura Blues. La Revista Electrónica CONTENIDO - DIRECTORIO ..……………………………………..…….. 2 “Un concepto distinto del blues y algo más…” EDITORIAL Al compás de los Rolling Stones (2) .......................…. 3 www.culturablues.com SESIONES DESDE LA CABINA Los Stones de Schrödinger Número 58 – marzo de 2016 (3) ..…………………………………………..……..…..………………………………………... 5 Derechos Reservados 04 – 2013 – 042911362800 – 203 Registro ante INDAUTOR DE COLECCIÓN El blues de los Rolling Stones. Parte 3 (2) .……..…8 COLABORACIÓN ESPECIAL ¿Quién lo dijo? 4 (2) ………….…. 17 Director general y editor: José Luis García Fernández BLUES EN EL REINO UNIDO The Rolling Stones – Timeline parte I (4) .......................................... 21 Subdirector general: José Luis García Vázquez ESPECIAL DE MEDIANOCHE Fito de la Parra: sus rollos y sus rastros (5) ……………….…….…..…….…. 26 Programación y diseño: Aida Castillo Arroyo COLABORACIÓN ESPECIAL La Esquina del Blues y otras músicas: Blues en México, recuento Consejo Editorial: de una década I (6) …………………………………………………………………….…. 34 María Luisa Méndez Flores Mario Martínez Valdez HUELLA AZUL Castalia Blues. Daniel Jiménez de Viri Roots & The Rootskers (7, 8 y 9) ………………………………………..……………..….… 38 Colaboradores en este número: BLUES A LA CARTA 10 años de rock & blues (2) .……………..... 45 1. José Luis García Vázquez CULTURA BLUES DE VISITA 2. José Luis García Fernández Ruta 61 con Shrimp City Slim (2 y 9) ................................................. 52 3. Yonathan Amador Gómez 4. Philip Daniels Storr CORTANDO RÁBANOS La penca que no retoña (10) ............ 55 5. Luis Eduardo Alcántara 6. Sandra Redmond LOS VERSOS DE NORMA Valor (11) ..………………………………… 57 7. María Luisa Méndez Flores 8. -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

Believarexic.Pdf

Young adult / fiction www.peachtree-online.com be • bulimarexic believarexic n. bu be • lim • liev • a • rex • ic liev Someone with an eating human disorder marked by an alternation between intense craving for and aversion ood belief in oneself. • to f a • rex H “Compelling and authentic, this story is impossible to put down. Believarexic is a raw, memorable reading experience.” • —Booklist ic “A powerful story of healing and self-acceptance.” —Kirkus Reviews 978-1-68263-007-5 $9.95 be•liev•a•rex•ic Believarexic TPB cover for BEA.indd 1 4/20/17 12:55 PM be•liev•a•rex•ic For Sam— We all have monsters. May yours be a friendly, loyal luck dragon who will fly you in the direction of your dreams. Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2015 by J. J. Johnson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Design and composition by Nicola Simmonds Carmack Printed May 2015 in Harrisonburg, VA, by R. R. Donnelley 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Johnson, J. J., 1973- Believarexic / JJ Johnson. pages cm ISBN 978-1-56145-771-7 Summary: An autobiographical novel in which fifteen-year-old Jennifer Johnson con- vinces her parents to commit her to the Eating Disorders Unit of an upstate New York psychiatric hospital in 1988, where the treatment for her bulimia and anorexia is not what she expects. -

“Local Forensic Scientists Have Made Attempts to Determine a Cause of Death...Their Tests Have Been Largely Inconclusive.”

volume 7 - issue 3 - tuesday, february 9, 2010 - uvm, burlington, vt uvm.edu/~watertwr by maxbookman by joshhegarty photo by emily shwartz ast Sunday night, February 7th, one attempts to examine the body and de- affect whales. We’re ruining the sea and however. of the most incredible and termine a cause of death, however since the atmosphere, can you really blame this Local authorities issued a statement on unbelievable things to ever appear they are not accustomed to working whale for being confused?” Friday, February 5th at noon, which had in Burlington, Vermont washed up with whales, their tests have been largely One man, who went only by Z, had this to say: on the beach. A North Atlantic Blue inconclusive. They have however deter- this to say, “That isn’t a normal whale. A “North Beach will be closed to all from Whale, weighing an estimated 150 tons mined that it was likely to be some sort week ago, an alien space craft dropped this point until Tuesday, February 9th, at with a length of 91 feet washed up dead of illness of the whale because no notable it here after they did their little experi- the earliest. The beach will reopen as soon on North Beach. If you find this informa- signs of injury could be found. ments on it. We gotta get rid of it soon or as the whale remains have been properly tion hard to swallow, I don’t blame you. This strange occurrence has also the eggs that they planted in its belly will removed and the shore has been combed I didn’t believe it myself until I visited raised questions about the capabilities of and cleaned to ensure the safety of all.” North Beach and saw it with my own One police officer, who asked to re- eyes. -

AN ANALYSIS of MODALITY in MAHER ZAIN's SONG

AN ANALYSIS OF MODALITY IN MAHER ZAIN’s SONG (NUMBER ONE FOR ME) A THESIS Submitted to the State Institute for Islamic Studies Padangsidimpuan as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for theGraduate Degree of Education (S.Pd) In English Written by FITRI RAHMADANI LUBIS Reg. Number. 13 340 0051 ENGLISH EDUCATIONAL DEPARTMENT TARBIYAH AND TEACHERS TRAINING FACULITY INSTITUTE FOR ISLAMIC STUDIES PADANGSIDIMPUAN 2017 NAME : FITRI RAHMADANI LUBIS REG. NO : 13 340 0051 FACULTY : TARBIYAH DAN ILMU KEGURUAN DEPARTMENT : TADRIS BAHASA INGGRIS (TBI-2) TITLE OF THESIS : AN ANALYSIS OF MODALITY IN MAHER ZAIN’S SONG (NUMBER ONE FOR ME) ABSTRACT In this research, the researcher analyzed mood and modality in Maher Zain song. The objective of this research are: 1) To find mood and modality in Maher Zain song. 2) To find dominant type of mood and modality in Maher Zain song. 3) To explain mood and modality in Maher Zain song. The purpose of this research was to analysis mood and modality in Maher Zain’s song (number one for me). This research hope this study can be useful to researcher. It will provide materials, it can be used by teacher to get mood and modality in Maher Zain’s song. This study is a qualitative research and uses content analysis. This research object is a song called number one for me song by Maher Zain, the lyrics of this song is very well known, especially by review those who love song, sung in various circles. The language contained in this song of course means that need to be revealed to gain an understanding it. -

Raw Thought: the Weblog of Aaron Swartz Aaronsw.Com/Weblog

Raw Thought: The Weblog of Aaron Swartz aaronsw.com/weblog 1 What’s Going On Here? May 15, 2005 Original link I’m adding this post not through blogging software, like I normally do, but by hand, right into the webpage. It feels odd. I’m doing this because a week or so ago my web server started making funny error messages and not working so well. The web server is in Chicago and I am in California so it took a day or two to get someone to check on it. The conclusion was the hard drive had been fried. When the weekend ended, we sent the disk to a disk repair place. They took a look at it and a couple days later said that they couldn’t do anything. The heads that normally read and write data on a hard drive by floating over the magnetized platter had crashed right into it. While the computer was giving us error messages it was also scratching away a hole in the platter. It got so thin that you could see through it. This was just in one spot on the disk, though, so we tried calling the famed Drive Savers to see if they could recover the rest. They seemed to think they wouldn’t have any better luck. (Please, plase, please, tell me if you know someplace to try.) I hadn’t backed the disk up for at least a year (in fairness, I was literally going to back it up when I found it giving off error messages) and the thought of the loss of all that data was crushing. -

The Biggest Legal Mistakes Physicians Make— and How to Avoid Them

The Biggest Legal Mistakes Physicians Make— And How to Avoid Them Edited by Steven Babitsky, Esq. James J. Mangraviti, Jr., Esq. SEAK, Inc. Falmouth, Massachusetts The Biggest Legal Mistakes Physicians Make—And How to Avoid Them Copyright © 2005 by SEAK, Inc. ISBN: 1-892904-26-8 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This book is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to constitute legal advice. An attorney or other appropriate source should be consulted if necessary. No part of this work may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information on retrieval and storage systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. For information, send a written request for permission to SEAK, Inc., P.O. Box 729, Falmouth, MA 02541. 508-457-1111. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.........................................................................................ix RELATED PRODUCTS BY SEAK, INC..............................................................xv ABOUT THE EDITORS ...................................................................................... xvii PREFACE ................................................................................................................xix PROLOGUE ............................................................................................................xxi FAILING TO VIEW LEGAL ISSUES PROPERLY..........................................................xxi