Acute Management of Spinal Cord Injury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spinal Cord Injury and Traumatic Brain Injury Research Grant Program Report 2020

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Spinal Cord Injury and Traumatic Brain Injury Research Grant Program Report January 15, 2020 Author About the Minnesota Office of Higher Education Alaina DeSalvo The Minnesota Office of Higher Education is a Competitive Grants Administrator cabinet-level state agency providing students with Tel: 651-259-3988 financial aid programs and information to help [email protected] them gain access to postsecondary education. The agency also serves as the state’s clearinghouse for data, research and analysis on postsecondary enrollment, financial aid, finance and trends. The Minnesota State Grant Program is the largest financial aid program administered by the Office of Higher Education, awarding up to $207 million in need-based grants to Minnesota residents attending eligible colleges, universities and career schools in Minnesota. The agency oversees other state scholarship programs, tuition reciprocity programs, a student loan program, Minnesota’s 529 College Savings Plan, licensing and early college awareness programs for youth. Minnesota Office of Higher Education 1450 Energy Park Drive, Suite 350 Saint Paul, MN 55108-5227 Tel: 651.642.0567 or 800.657.3866 TTY Relay: 800.627.3529 Fax: 651.642.0675 Email: [email protected] Table of Contents Introduction 1 Spinal Cord Injury and Traumatic Brain Injury Advisory Council 1 FY 2020 Proposal Solicitation Schedule -

Suplento1 Volumen 71 En

S1 Volumen 71 Mayo 2015 Revista Española de Vol. 71 Supl. 1 • Mayo 2015 Vol. Clínica e Investigación Órgano de expresión de la Sociedad Española de SEINAP Investigación en Nutrición y Alimentación en Pediatría Sumario XXX CONGRESO DE LA SOCIEDAD espaÑOLA DE CUIDADOS INTENSIVOS PEDIÁTRICOS Toledo, 7-9 de mayo de 2015 MESA REDONDA: ¿HACIA DÓNDE VAMOS EN LA MESA REDONDA: EL PACIENTE AGUDO MONITORIZACIÓN? CRONIFICADO EN UCIP 1 Monitorización mediante pulsioximetría: ¿sólo saturación 47 Nutrición en el paciente crítico de larga estancia en UCIP. de oxígeno? P. García Soler Z. Martínez de Compañón Martínez de Marigorta 3 Avances en la monitorización de la sedoanalgesia. S. Mencía 53 Traqueostomía, ¿cuándo realizarla? M.A. García Teresa Bartolomé y Grupo de Sedoanalgesia de la SECIP 60 Los cuidados de enfermería, ¿un reto? J.M. García Piñero 8 Avances en neuromonitorización. B. Cabeza Martín CHARLA-COLOQUIO SESIÓN DE PUESTA AL DÍA: ¿ES BENEFICIOSA LA 64 La formación en la preparación de las UCIPs FLUIDOTERAPIA PARA MI PACIENTE? españolas frente al riesgo de epidemias infecciosas. 13 Sobrecarga de líquidos y morbimortalidad asociada. J.C. de Carlos Vicente M.T. Alonso 68 Lecciones aprendidas durante la crisis del Ébola: 20 Estrategias de fluidoterapia racional en Cuidados experiencia del intensivista de adultos. J.C. Figueira Intensivos Pediátricos. P. de la Oliva Senovilla Iglesias 72 El niño con enfermedad por virus Ébola: un nuevo reto MESA REDONDA: INDICADORES DE CALIDAD para el intensivista pediátrico. E. Álvarez Rojas DE LA SECIP 23 Evolución de la cultura de seguridad en UCIP. MESA REDONDA: UCIP ABIERTAS 24 HORAS, La comunicación efectiva. -

Spinal Injury

SPINAL INJURY Presented by:- Bhagawati Ray DEFINITION Spinal cord injury (SCI) is damage to the spinal cord that results in a loss of function such as mobility or feeling. TYPES OF SPINAL CORD INJURY Complete Spinal Cord Injuries Complete paraplegia is described as permanent loss of motor and nerve function at T1 level or below, resulting in loss of sensation and movement in the legs, bowel, bladder, and sexual region. Arms and hands retain normal function. INCOMPLETE SPINAL CORD INJURIES Anterior cord syndrome Anterior cord syndrome, due to damage to the front portion of the spinal cord or reduction in the blood supply from the anterior spinal artery, can be caused by fractures or dislocations of vertebrae or herniated disks. CENTRAL CORD SYNDROME Central cord syndrome, almost always resulting from damage to the cervical spinal cord, is characterized by weakness in the arms with relative sparing of the legs, and spared sensation in regions served by the sacral segments. POSTERIOR CORD SYNDROME Posterior cord syndrome, in which just the dorsal columns of the spinal cord are affected, is usually seen in cases of chronic myelopathy but can also occur with infarction of the posterior spinal artery. BROWN-SEQUARD SYNDROME Brown-Sequard syndrome occurs when the spinal cord is injured on one side much more than the other. It is rare for the spinal cord to be truly hemisected (severed on one side), but partial lesions due to penetrating wounds (such as gunshot or knife wounds) or fractured vertebrae or tumors are common. CAUDA EQUINASYNDROME Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a condition that occurs when the bundle of nerves below the end of the spinal cord known as the cauda equina is damaged. -

T5 Spinal Cord Injuries

Spinal Cord (2020) 58:1249–1254 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0506-7 ARTICLE Predictors of respiratory complications in patients with C5–T5 spinal cord injuries 1 2,3 3,4 1,5 1,5 Júlia Sampol ● Miguel Ángel González-Viejo ● Alba Gómez ● Sergi Martí ● Mercedes Pallero ● 1,4,5 3,4 1,4,5 1,4,5 Esther Rodríguez ● Patricia Launois ● Gabriel Sampol ● Jaume Ferrer Received: 19 December 2019 / Revised: 12 June 2020 / Accepted: 12 June 2020 / Published online: 24 June 2020 © The Author(s), under exclusive licence to International Spinal Cord Society 2020 Abstract Study design Retrospective chart audit. Objectives Describing the respiratory complications and their predictive factors in patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injuries at C5–T5 level during the initial hospitalization. Setting Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona. Methods Data from patients admitted in a reference unit with acute traumatic injuries involving levels C5–T5. Respiratory complications were defined as: acute respiratory failure, respiratory infection, atelectasis, non-hemothorax pleural effusion, 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: pulmonary embolism or haemoptysis. Candidate predictors of these complications were demographic data, comorbidity, smoking, history of respiratory disease, the spinal cord injury characteristics (level and ASIA Impairment Scale) and thoracic trauma. A logistic regression model was created to determine associations between potential predictors and respiratory complications. Results We studied 174 patients with an age of 47.9 (19.7) years, mostly men (87%), with low comorbidity. Coexistent thoracic trauma was found in 24 (19%) patients with cervical and 35 (75%) with thoracic injuries (p < 0.001). Respiratory complications were frequent (53%) and were associated to longer hospital stay: 83.1 (61.3) and 45.3 (28.1) days in patients with and without respiratory complications (p < 0.001). -

Neurologic Deterioration Secondary to Unrecognized Spinal Instability Following Trauma–A Multicenter Study

SPINE Volume 31, Number 4, pp 451–458 ©2006, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Neurologic Deterioration Secondary to Unrecognized Spinal Instability Following Trauma–A Multicenter Study Allan D. Levi, MD, PhD,* R. John Hurlbert, MD, PhD,† Paul Anderson, MD,‡ Michael Fehlings, MD, PhD,§ Raj Rampersaud, MD,§ Eric M. Massicotte, MD,§ John C. France, MD, Jean Charles Le Huec, MD, PhD,¶ Rune Hedlund, MD,** and Paul Arnold, MD†† Study Design. A retrospective study was undertaken their neurologic injury. The most common reason for the that evaluated the medical records and imaging studies of missed injury was insufficient imaging studies (58.3%), a subset of patients with spinal injury from large level I while only 33.3% were a result of misread radiographs or trauma centers. 8.3% poor quality radiographs. The incidence of missed Objective. To characterize patients with spinal injuries injuries resulting in neurologic injury in patients with who had neurologic deterioration due to unrecognized spine fractures or strains was 0.21%, and the incidence as instability. a percentage of all trauma patients evaluated was 0.025%. Summary of Background Data. Controversy exists re- Conclusions. This multicenter study establishes that garding the most appropriate imaging studies required to missed spinal injuries resulting in a neurologic deficit “clear” the spine in patients suspected of having a spinal continue to occur in major trauma centers despite the column injury. Although most bony and/or ligamentous presence of experienced personnel and sophisticated im- spine injuries are detected early, an occasional patient aging techniques. Older age, high impact accidents, and has an occult injury, which is not detected, and a poten- patients with insufficient imaging are at highest risk. -

Update on Critical Care for Acute Spinal Cord Injury in the Setting of Polytrauma

NEUROSURGICAL FOCUS Neurosurg Focus 43 (5):E19, 2017 Update on critical care for acute spinal cord injury in the setting of polytrauma *John K. Yue, BA,1,2 Ethan A. Winkler, MD, PhD,1,2 Jonathan W. Rick, BS,1,2 Hansen Deng, BA,1,2 Carlene P. Partow, BS,1,2 Pavan S. Upadhyayula, BA,3 Harjus S. Birk, MD,3 Andrew K. Chan, MD,1,2 and Sanjay S. Dhall, MD1,2 1Department of Neurological Surgery, University of California, San Francisco; 2Brain and Spinal Injury Center, Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, San Francisco; and 3Department of Neurological Surgery, University of California, San Diego, California Traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) often occurs in patients with concurrent traumatic injuries in other body systems. These patients with polytrauma pose unique challenges to clinicians. The current review evaluates existing guidelines and updates the evidence for prehospital transport, immobilization, initial resuscitation, critical care, hemodynamic stabil- ity, diagnostic imaging, surgical techniques, and timing appropriate for the patient with SCI who has multisystem trauma. Initial management should be systematic, with focus on spinal immobilization, timely transport, and optimizing perfusion to the spinal cord. There is general evidence for the maintenance of mean arterial pressure of > 85 mm Hg during imme- diate and acute care to optimize neurological outcome; however, the selection of vasopressor type and duration should be judicious, with considerations for level of injury and risks of increased cardiogenic complications in the elderly. Level II recommendations exist for early decompression, and additional time points of neurological assessment within the first 24 hours and during acute care are warranted to determine the temporality of benefits attributable to early surgery. -

Posttraumatic Stress Following Spinal Cord Injury: a Systematic Review of Risk and Vulnerability Factors

Spinal Cord (2017) 55, 800–811 & 2017 International Spinal Cord Society All rights reserved 1362-4393/17 www.nature.com/sc REVIEW Posttraumatic stress following spinal cord injury: a systematic review of risk and vulnerability factors K Pollock1,3, D Dorstyn1,3, L Butt2 and S Prentice1 Objectives: To summarise quantitatively the available evidence relating to pretraumatic, peritraumatic and posttraumatic characteristics that may increase or decrease the risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following spinal cord injury (SCI). Study design: Systematic review. Methods: Seventeen studies were identified from the PubMed, PsycInfo, Embase, Scopus, CINAHL, Web of Science and PILOTS databases. Effect size estimates (r) with associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs), P-values and fail-safe Ns were calculated. Results: Individual studies reported medium-to-large associations between factors that occurred before (psychiatric history r = 0.48 (95% CI, 0.23–0.79) P = 0.01) or at the time of injury (tetraplegia r = − 0.36 (95% CI, − 0.50 to − 0.19) Po0.01). Postinjury factors had the strongest pooled effects: depressed mood (rw = 0.64, (95% CI, 0.54–0.72)), negative appraisals (rw = 0.63 (95% CI, 0.52– 0.72)), distress (rw = 0.57 (95% CI, 0.50–0.62)), anxiety (rw = 0.56 (95% CI, 0.49–0.61)) and pain severity (rw = 0.35 (95% CI, 0.27– 0.43)) were consistently related to worsening PTSD symptoms (Po0.01). Level of injury significantly correlated with current PTSD severity for veteran populations (QB (1) = 18.25, Po0.001), although this was based on limited data. -

Pediatric Shock

REVIEW Pediatric shock Usha Sethuraman† & Pediatric shock accounts for significant mortality and morbidity worldwide, but remains Nirmala Bhaya incompletely understood in many ways, even today. Despite varied etiologies, the end result †Author for correspondence of pediatric shock is a state of energy failure and inadequate supply to meet the metabolic Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Division of demands of the body. Although the mortality rate of septic shock is decreasing, the severity Emergency Medicine, is on the rise. Changing epidemiology due to effective eradication programs has brought in Carman and Ann Adams new microorganisms. In the past, adult criteria had been used for the diagnosis and Department of Pediatrics, 3901 Beaubien Boulevard, management of septic shock in pediatrics. These have been modified in recent times to suit Detroit, MI 48201, USA the pediatric and neonatal population. In this article we review the pathophysiology, Tel.: +1 313 745 5260 epidemiology and recent guidelines in the management of pediatric shock. Fax: +1 313 993 7166 [email protected] Shock is an acute syndrome in which the circu- to generate ATP. It is postulated that in the face of latory system is unable to provide adequate oxy- prolonged systemic inflammatory insult, overpro- gen and nutrients to meet the metabolic duction of cytokines, nitric oxide and other medi- demands of vital organs [1]. Due to the inade- ators, and in the face of hypoxia and tissue quate ATP production to support function, the hypoperfusion, the body responds by turning off cell reverts to anaerobic metabolism, causing the most energy-consuming biophysiological acute energy failure [2]. -

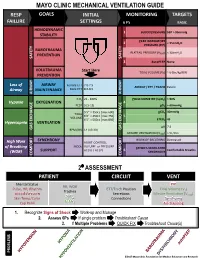

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Approach to Shock.” These Podcasts Are Designed to Give Medical Students an Overview of Key Topics in Pediatrics

PedsCases Podcast Scripts This is a text version of a podcast from Pedscases.com on “Approach to Shock.” These podcasts are designed to give medical students an overview of key topics in pediatrics. The audio versions are accessible on iTunes or at www.pedcases.com/podcasts. Approach to Shock Developed by Dr. Dustin Jacobson and Dr Suzanne Beno for PedsCases.com. December 20, 2016 My name is Dustin Jacobson, a 3rd year pediatrics resident from the University of Toronto. This podcast was supervised by Dr. Suzanne Beno, a staff physician in the division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine at the University of Toronto. Today, we’ll discuss an approach to shock in children. First, we’ll define shock and understand it’s pathophysiology. Next, we’ll examine the subclassifications of shock. Last, we’ll review some basic and more advanced treatment for shock But first, let’s start with a case. Jonny is a 6-year-old male who presents with lethargy that is preceded by 2 days of a diarrheal illness. He has not urinated over the previous 24 hours. On assessment, he is tachycardic and hypotensive. He is febrile at 40 degrees Celsius, and is moaning on assessment, but spontaneously breathing. We’ll revisit this case including evaluation and management near the end of this podcast. The term “shock” is essentially a ‘catch-all’ phrase that refers to a state of inadequate oxygen or nutrient delivery for tissue metabolic demand. This broad definition incorporates many causes that eventually lead to this end-stage state. Basic oxygen delivery is determined by cardiac output and content of oxygen in the blood. -

Hypothesis Spinal Shock and `Brain Death': Somatic Pathophysiological

Spinal Cord (1999) 37, 313 ± 324 ã 1999 International Medical Society of Paraplegia All rights reserved 1362 ± 4393/99 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/sc Hypothesis Spinal shock and `brain death': Somatic pathophysiological equivalence and implications for the integrative-unity rationale DA Shewmon*,1 1Pediatric Neurology, UCLA Medical School, Los Angeles, California, USA The somatic pathophysiology of high spinal cord injury (SCI) not only is of interest in itself but also sheds light on one of the several rationales proposed for equating `brain death' (BD) with death, namely that the brain confers integrative unity upon the body, which would otherwise constitute a mere conglomeration of cells and tissues. Insofar as the neuropathology of BD includes infarction down to the foramen magnum, the somatic pathophysiology of BD should resemble that of cervico-medullary junction transection plus vagotomy. The endocrinologic aspects can be made comparable either by focusing on BD patients without diabetes insipidus or by supposing the victim of high SCI to have pre-existing therapeutically compensated diabetes insipidus. The respective literatures on intensive care for BD organ donors and high SCI corroborate that the two conditions are somatically virtually identical. If SCI victims are alive at the level of the `organism as a whole', then so must be BD patients (the only signi®cant dierence being consciousness). Comparison with SCI leads to the conclusion that if BD is to be equated with death, a more coherent reason must be adduced than that the body as a biological organism is dead. Keywords: brain death; spinal cord injury; spinal shock; integrative functions; somatic integrative unity; organism as a whole Introduction Spinal shock is a transient functional depression of the society; its legal de®nition is culturally relative, and structurally intact cord below a lesion, following acute most modern societies happen to have chosen to spinal cord injury (SCI). -

Where Does Central Cord Syndrome Fit Into the Spinal Cord Injury Spectrum?

Central cord syndrome Laura Snyder, MD FAANS Director of Neurotrauma Minimally Invasive Spine Surgeon Barrow Neurological InsAtute St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center Where does central cord syndrome fit into the spinal cord injury spectrum? Spinal Cord Injury • Complete • No preservaAon of any motor and/or sensory funcAon more than 3 segments below the level of injury in the absence of spinal shock • Incomplete • Some preservaAon of motor and/or sensory funcAon below level of injury including • Palpable or visible muscle contracAon • Perianal sensaAon • Voluntary anal contracAon Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury • Central cord syndrome • Anterior cord syndrome • Brown-Sequard syndrome • Posterior Cord Syndrome Spinal Cord Injury Epidemiology • 11,000 cases/year • 34% incomplete tetraplegia • Most common is Central Cord Syndrome • 11% incomplete paraplegia • 47% complete injuries The Cause • Most commonly acute hyperextension injury in older paAent with pre-exisAng acquired stenosis • Stenosis can be result of • Bony hypertrophy (anterior or posterior spurs) • Infolding of redundant ligamentum flavum posteriorly • Anterior disc bulge or herniaAon • Congenital spinal stenosis Abnormal Loading of Spinal Cord can cause Spinal Cord Injury Nerve Compression at Rest Combine pre-exisAng compression with hyperextension => Central Cord Syndrome Most Common PresentaAon • Blow to upper face or forehead • Forward fall (anyAme you see an elderly paAent with a fall in which they hit their head) • Motor Vehicle accident • SporAng injuries Pathomechanics