By John Batten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mill Cottage the Mill Cottage Cockercombe, Over Stowey, Bridgwater, TA5 1HJ Taunton 8 Miles

The Mill Cottage The Mill Cottage Cockercombe, Over Stowey, Bridgwater, TA5 1HJ Taunton 8 Miles • 4.2 Acres • Stable Yard • Mill Leat & Stream • Parkland and Distant views • 3 Reception Rooms • Kitchen & Utility • 3 Bedrooms (Master En-Suite) • Garden Office Guide price £650,000 Situation The Mill Cottage is situated in the picturesque hamlet of Cockercombe, within the Quantock Hills, England's first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. This is a very attractive part of Somerset, renowned for its beauty, with excellent riding, walking and other country pursuits. There is an abundance of footpaths and bridleways. The village of Nether Stowey is 2 miles away and Kingston St A charming Grade II Listed cottage with yard, stabling, 4.2 Acres of Mary is 5 miles away. Taunton, the County Town of Somerset, is some 8 miles to the South. Nether Stowey is an attractive centre land and direct access to the Quantock Hills. with an extensive range of local facilities, which are further supplemented by the town of Bridgwater, some 8 miles to the East. Taunton has a wide range of facilities including a theatre, county cricket ground and racecourse. Taunton is well located for national communications, with the M5 motorway at Junction 25 and there is an excellent intercity rail service to London Paddington (an hour and forty minutes). The beautiful coastline at Kilve is within 15 minutes drive. Access to Exmoor and the scenic North Somerset coast is via the A39 or through the many country roads in the area. The Mill Cottage is in a wonderful private location in a quiet lane, with clear views over rolling countryside. -

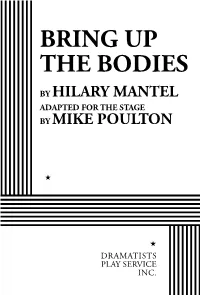

Bring up the Bodies

BRING UP THE BODIES BY HILARY MANTEL ADAPTED FOR THE STAGE BY MIKE POULTON DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. BRING UP THE BODIES Copyright © 2016, Mike Poulton and Tertius Enterprises Ltd Copyright © 2014, Mike Poulton and Tertius Enterprises Ltd Bring Up the Bodies Copyright © 2012, Tertius Enterprises Ltd All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of BRING UP THE BODIES is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for BRING UP THE BODIES are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. -

Charlton Mackrell Cofe Primary School History

Charlton Mackrell CofE Primary School History Education in The Charltons first began with Sunday Schools, but Church Daily Schools were started in both Charlton Mackrell and Charlton Adam in 1830. The school in Adam closed and an Infants School only was opened from 1865 until 1917. In 1846, Charlton Mackrell School had 82 pupils of all ages, but only one room and a small house for the teacher. We don't know whether it was on this site or in the grounds of the Rectory, which is now called "The Court". The Rector was the Reverend William Thomas Parr Brymer, who began a complete restoration of the church in 1847. We believe he also planned the unique school building, designed by the architect C E Giles, which we still enjoy today. Certainly in 1846 he left money in his will to pay for the schoolteacher and other running costs of the school, as recorded on the brass plaque near the altar in Charlton Mackrell Church. After he died in August 1852, his brother James Snaith Brymer paid for this school building as a memorial to him and the recent restoration of the main schoolroom ceiling has revealed the commemorative inscription around the walls. The first schoolteacher we know about was Miss Elizabeth Rooke, from London. She left early in 1853, perhaps due to the new school building. After her were schoolmasters, W. Jackson, W. Wrigley, and then William Tyler. William Tyler was the schoolmaster and the church organist for nearly 10 years from 1856. There were also paid pupil teachers and monitors, as well as a schoolmistress for the Infants class. -

South Somerset District Council Asset of Community Value Register

South Somerset District Council Asset of Community Value Register Reference Nominator Name, address and Date entered Current use of Proposed use of Date agreed Date SSDC Date of end of initial Number of Date of end of full Number of written Date to be removed Property protected from Comments (name of group) postcode of on register property/land property/land by District received moratorum period (6 Expressions of moratorum period (6 intentions to bid from register (auto-fill nomination/moritorium Property Council notification of weeks after date of Interest received months after date of received ie. 5 years after listing) triggers (18 months from intention to sell notification to sell is notification to sell is notification of intention to received) received) sell) ACV32 Long Sutton Long Sutton Stores 30/03/2016 Village stores Village stores 30/03/2016 30/03/2021 Village Stores sold as a Parish Council The Green going concern therefore an Long Sutton 'Exempt Disposal' and Somerset remains on register. TA10 9HT ACV33 Yeovil Town Huish Park Stadium 21/04/2016 Playing association Playing association 21/04/2016 26/11/2020 07/01/2021 1 26/05/2021 21/04/2021 Supporters Lufton Way football football and other Society Ltd Yeovil leisure activities Somerset BA22 8YF AVC 34 Yeovil Town Huish Park 21/04/2016 Football pitches, Leisure 21/04/2016 26/11/2020 07/01/2021 1 26/05/2021 21/04/2021 Supporters surrounding land car parks, Society Ltd Lufton Way community space Yeovil Somerset BA22 8YF ACV35 Martock Parish The Post Office 26/07/2016 Post Office -

Edward III, Vol. 16, P

136 CALENDAR OF PATENT ROLLS. 1375. Membrane 33d — cont. May6. Richard,earl of Arundel and Surrey, Thomas de Ponynges, Westminster. Robert Bealknap,Edward de Sancto Johanne,John de Waleys, William de Cobeham,HenryAsty,Roger Dalyngrugge,Robert de Halsham and Nicholas Wilcombe ; Sussex. May16. Nicholas de Audeleye,Gilbert Talbot, Walter Perle, David Westminster. Hanemere,John Gour and John de Oldecastel ; Hereford. May20. Henryde Percy, William de Aton, Roger de Kirketon,Roger Westminster. de Fulthorp, John Conestable of Halsham, Thomas de Wythornwyk,Peter de Grymmesby, Robert de Lorymer, Thomas Saltmersh and John Dayvill ; the East Riding,co. York. July5. William de Monte Acuto,earl of Salisbury,William Tauk,Robert Westminster. le Fitz Payn,John de la Hale,Edmund Fitz Herberd,Walter Perle,Roger Manyngford,William Payn and Edmund Strode ; Dorset. July5. Hugh, earl of Stafford,Guyde Bryan, Peter le Veel,Walter Westminster. Perle, David Hanemere,Robert Palet, John Clifford and Thomas Styward ; Gloucester. ' chivaler,' July15. Hugh de Courtenay,earl of Devon,Guyde Bryene, Westminster. William Botreaux,' chivaler,'William Tauk,HenryPercehay, William Caryand John Cary; Devon. Dec. 6. William de Wychyngham,Thomas de Ingelby,John de Basynges, Westminster. Simon Warde, John de Wittelesbury,Nicholas Grene and Walter Scarle ; Rutland. ByC. Sept. 25. John de Vernoun,John Golafre,Richard de Adderbury,Reynold Westminster. Malyns,Walter Perle,David Hanemere,John de Baldyngton, Robert de Wyghthull and John Laundeles ; Oxford. Nov. 10. Thomas de Ingelby,Roger de Kirketon,Roger de Fulthorp, Westminster. Walter Frost, John de Lokton and Thomas de Beverle ; the libertyof St. John of Beverley. Dec. 6. William Latymer,John de Cobham,Robert Bealknap,Reynold Westminster. -

The Monuments of the Seymours in Great Bedwyn Church, Wilts

Archaeological Journal ISSN: 0066-5983 (Print) 2373-2288 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raij20 The Monuments Of The Seymours In Great Bedwyn Church, Wilts W. Brailsford To cite this article: W. Brailsford (1882) The Monuments Of The Seymours In Great Bedwyn Church, Wilts, Archaeological Journal, 39:1, 407-409, DOI: 10.1080/00665983.1882.10852050 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1882.10852050 Published online: 14 Jul 2014. Submit your article to this journal View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=raij20 Download by: [University of Exeter] Date: 01 June 2016, At: 17:05 THE MONUMENTS OF THE SEYMOURS IN GREAT ' BEDWYN CHURCH, WILTS.1 By W. BRAILSFORD. Great Bedwyn is at tlie present time a little village in the county of Wiltshire. It must formerly have heen of larger importance, con- sidering that it sent two members to parliament. Traces of Roman occupation have from time to time been discovered, and a tesselated pavement was one of the antiquities long preserved. A spiked head of a mace made of bronze was found in a well and exhibited some few years since at a meeting of Arcliieologists held at Salisbury. The church is now the principal feature in the place, and has unfortunately undergone very extensive restoration. In the churchyard is a stone cross, and though, as usual, the summit has suffered mutilation, the shaft, pedestal, and steps are in good preservation. In the interior of the church there are several interesting monuments, particularly those connected with the great Seymour family. -

River Brue's Historic Bridges by David Jury

River Brue’s Historic Bridges By David Jury The River Brue’s Historic Bridges In his book "Bridges of Britain" Geoffrey Wright writes: "Most bridges are fascinating, many are beautiful, particularly those spanning rivers in naturally attractive settings. The graceful curves and rhythms of arches, the texture of stone, the cold hardness of iron, the stark simplicity of iron, form constant contrasts with the living fluidity of the water which flows beneath." I cannot add anything to that – it is exactly what I see and feel when walking the rivers of Somerset and discover such a bridge. From source to sea there are 58 bridges that span the River Brue, they range from the simple plank bridge to the enormity of the structures that carry the M5 Motorway. This article will look at the history behind some of those bridges. From the river’s source the first bridge of note is Church Bridge in South Brewham, with it’s downstream arch straddling the river between two buildings. Figure 1 - Church Bridge South Brewham The existing bridge is circa 18th century but there was a bridge recorded here in 1258. Reaching Bruton, we find Church Bridge described by John Leland in 1525 as the " Est Bridge of 3 Archys of Stone", so not dissimilar to what we have today, but in 1757 the bridge was much narrower “barely wide enough for a carriage” and was widened on the east side sometime in the early part of the 19th century. Figure 2 - Church Bridge Bruton Close by we find that wonderful medieval Bow Bridge or Packhorse Bridge constructed in the 15th century with its graceful slightly pointed chamfered arch. -

Jane Seymour 1509 – 24 October 1537

Jane Seymour 1509 – 24 October 1537 Jane was the eldest of the eight children of Sir John Seymour of Wolf Hall, Savernake, Wiltshire and his wife Margaret, daughter of Sir John Wentworth of Nettlestead, Suffolk. According to court gossip and an inscription on a miniature by Nicholas Hilliard she was born about 1509, probably at Wolf Hall. There is unsupported evidence that as a young woman Jane was a maid of honour to Mary, queen of Louis XII of France, who was Henry VIII's sister. She was subsequently appointed as lady in waiting to Catherine of Aragon and, on Catherine's divorce, to the same role with Anne Boleyn. She was described as of middle stature , of no great beauty, of pale complexion and commended for her intelligence. In February 1536, Henry VIII was writing to her with dishonourable proposals as well as money which Jane returned to him with the comment that her honour was her fortune. It appears that Jane was only prepared to withstand his suggestions unless she was his wife. It was his anxiety to set Jane in Anne's place that ensured that legal proceedings were taken against the latter. Jane at this time kept herself removed from the king outside London. Before 15 May 1536, the date of Anne Boleyn's trial, Jane moved to a house on the Thames and was brought news of Anne's condemnation and beheading four days later. It is understood that Archbishop Cranmer issued a dispensation for the marriage that day and the betrothal took place the following morning. -

Notes on the Seymour Family. by Noel Murphy

1 Notes on the Seymour family. By Noel Murphy. My thanks to the Friends Historical Library, Dublin for permission to use material from their Archives. This material is shown in Italics below. William Hartwell = Mayor 1659 of Limerick. Edward Seymour = Miss Hartwell Only son. John Seymour = Jane Wroughton Sh. 1708 dau. of Seymour Wroughton My. 1720 of Wiltshire. D. 1735 A Sadler. William = Jane Wight John Richard Walter = Mary James = Miss [Margaret] Holland A Sadler Sh. 1730 Sh. 1742 Sh 1728 dau of Ezekiel Holland. The 1713 Mayor and 1699 D. 12/7/1782. Sheriff who died in 1728. 1 Rev John = Grizzle Hobart. (Griselda). John Mary Lucy James B. Co-heir to William Hobart. Bt.16/10/1726. 13/11/1728. 02/07/1732. (M. 19/10/1761. St Anne’s Fm. 20/2/1747 Fm. 20/2/1747 D. 1795 Dublin. Name given as Hubbart). 2 William Michael Rev John = Catherine Mullett Richard R.N. Frances = Robert Ormsby B.c. 1766 B. 1768 B.c. 1772 Widow of James K.I.A. D. 1797 D. 9/7/1834 Jacob D. 1805 Admiral 3 M. Nov 1796. Rev John. ================== Alderman John Seymour = Jane Wroughton D. 1735 John Seymour = Frances Crossley Dublin B. B. M. D. D. April 1760 Aaron Crossley Seymour = Margaret Cassan. ================== Familysearch: - James Seymour = Margaret James Seymour = Jane Mary Lucy James Jane Bt. 16 Oct 1726 Bt.13 Nov 1728. Bt. 2 July 1732. Bt. 1 March 1736. 2 Is this James Seymour the 1728 Sheriff? Is Margaret, his wife, the daughter of Ezekiel Holland? Did she die after giving birth to their son James? And did James, the Sheriff remarry a Jane and have a daughter with her, naturally called Jane after her mother? James, the Freeman admitted in 1747 is positively identified as the son of James Seymour, Burgess. -

Long, W, Dedications of the Somersetshire Churches, Vol 17

116 TWENTY-THIKD ANNUAL MEETING. (l[ki[rk^. BY W, LONG, ESQ. ELIEVING that a Classified List of the Dedications jl:> of the Somersetshire Churches would be interesting and useful to the members of the Society, I have arranged them under the names of the several Patron Saints as given by Ecton in his “ Thesaurus Kerum Ecclesiasticarum,^^ 1742 Aldhelm, St. Broadway, Douiting. All Saints Alford, Ashcot, Asholt, Ashton Long, Camel West, Castle Cary, Chipstaple, Closworth, Corston, Curry Mallet, Downhead, Dulverton, Dun- kerton, Farmborough, Hinton Blewitt, Huntspill, He Brewers, Kingsdon, King Weston, Kingston Pitney in Yeovil, Kingston] Seymour, Langport, Martock, Merriot, Monksilver, Nine- head Flory, Norton Fitzwarren, Nunney, Pennard East, PoLntington, Selworthy, Telsford, Weston near Bath, Wolley, Wotton Courtney, Wraxhall, Wrington. DEDICATION OF THE SOMERSET CHURCHES. 117 Andrew, St. Aller, Almsford, Backwell, Banwell, Blagdon, Brimpton, Burnham, Ched- dar, Chewstoke, Cleeve Old, Cleve- don, Compton Dundon, Congresbury, Corton Dinham, Curry Rivel, Dowlish Wake, High Ham, Holcombe, Loxton, Mells, Northover, Stoke Courcy, Stoke under Hambdon, Thorn Coffin, Trent, Wells Cathedral, White Staunton, Withypool, Wiveliscombe. Andrew, St. and St. Mary Pitminster. Augustine, St. Clutton, Locking, Monkton West. Barnabas, St. Queen’s Camel. Bartholomew, St. Cranmore West, Ling, Ubley, Yeovilton. Bridget, St. Brean, Chelvy. Catherine, St. Drayton, Montacute, Swell. Christopher, St. Lympsham. CONGAR, St. Badgworth. Culborne, St. Culbone. David, St. Barton St. David. Dennis, St. Stock Dennis. Dubritius, St. Porlock. Dun STAN, St. Baltonsbury. Edward, St. Goathurst. Etheldred, St. Quantoxhead West. George, St. Beckington, Dunster, Easton in Gordano, Hinton St. George, Sand- ford Bret, Wembdon, Whatley. Giles, St. Bradford, Cleeve Old Chapel, Knowle St. Giles, Thurloxton. -

Langport and Frog Lane

English Heritage Extensive Urban Survey An archaeological assessment of Langport and Frog Lane Miranda Richardson Jane Murray Corporate Director Culture and Heritage Directorate Somerset County Council County Hall TAUNTON Somerset TA1 4DY 2003 SOMERSET EXTENSIVE URBAN SURVEY LANGPORT AND FROG LANE ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT by Miranda Richardson CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................... .................................. 3 II. MAJOR SOURCES ............................... ................................... 3 1. Primary documents ............................ ................................ 3 2. Local histories .............................. .................................. 3 3. Maps ......................................... ............................... 3 III. A BRIEF HISTORY OF LANGPORT . .................................. 3 IV. THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF LANGPORT . .............................. 4 1. PREHISTORIC and ROMAN ........................ ............................ 4 2. SAXON ........................................ .............................. 7 3. MEDIEVAL ..................................... ............................. 9 4. POST-MEDIEVAL ................................ ........................... 14 5. INDUSTRIAL (LATE 18TH AND 19TH CENTURY) . .......................... 15 6. 20TH CENTURY ................................. ............................ 18 V. THE POTENTIAL OF LANGPORT . ............................... 19 1. Research interests........................... ................................. -

Information Requests PP B3E 2 County Hall Taunton Somerset TA1 4DY J Roberts

Information Requests PP B3E 2 Please ask for: Simon Butt County Hall FOI Reference: 1700165 Taunton Direct Dial: 01823 359359 Somerset Email: [email protected] TA1 4DY Date: 3 November 2016 J Roberts ??? Dear Sir/Madam Freedom of Information Act 2000 I can confirm that the information you have requested is held by Somerset County Council. Your Request: Would you be so kind as to please supply information regarding which public service bus routes within the Somerset Area are supported by funding subsidies from Somerset County Council. Our Response: I have listed the information that we hold below Registered Local Bus Services that receive some level of direct subsidy from Somerset County Council as at 1 November 2016 N8 South Somerset DRT 9 Donyatt - Crewkerne N10 Ilminster/Martock DRT C/F Bridgwater Town Services 16 Huish Episcopi - Bridgwater 19 Bridgwater - Street 25 Taunton - Dulverton 51 Stoke St. Gregory - Taunton 96 Yeovil - Chard - Taunton 162 Frome - Shepton Mallet 184 Frome - Midsomer Norton 198 Dulverton - Minehead 414/424 Frome - Midsomer Norton 668 Shipham - Street 669 Shepton Mallet - Street 3 Taunton - Bishops Hull 1 Bridgwater Town Service N6 South Petherton - Martock DRT 5 Babcary - Yeovil 8 Pilton - Yeovil 11 Yeovil Town Service 19 Bruton - Yeovil 33 Wincanton - Frome 67 Burnham - Wookey Hole 81 South Petherton - Yeovil N11 Yeovilton - Yeovil DRT 58/412 Frome to Westbury 196 Glastonbury Tor Bus Cheddar to Bristol shopper 40 Bridport - Yeovil 53 Warminster - Frome 158 Wincanton - Shaftesbury 74/212 Dorchester