ESSA-Sport National Report – Denmark 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Report

COMPARATIVE REPORT Italy, Spain, Denmark and Greece Qualification for Minor Migrants education and Learning Open access - On line Teacher Training Reference number: 2017-1-IT02-KA201-036610 Spanish QUAMMELOT Team (González-Monteagudo, J., Zamora-Serrato, M., Moreno-Fernández, O., Guichot-Muñoz, E., Ferreras-Listán, M., Puig-Gutiérrez, M., Pineda-Alfonso, J. A.) University of Seville (Coordinator: Dr. José González-Monteagudo) Seville, Spain, October 2018 TABLE OF CONTENT 1. NATIONAL CONTEXT ON MIGRATION AND MENAS ............................................................ 2 1.1. Evolution of the migratory process................................................................................ 2 1.2. MENAS/UFM .................................................................................................................. 3 1.3. General figures ............................................................................................................... 5 2. LEGISLATION IN ATTENTION TO THE IMMIGRANT POPULATION ....................................... 8 2.1. Legislation applicable to unaccompanied immigrant minors. ..................................... 10 3. STRUCTURE OF THE SCHOOL SYSTEM ................................................................................ 13 3.1. Legislation in the educational context: attention to immigrants ................................ 14 3.2. Teacher training: intercultural education .................................................................... 16 4. IMMIGRANT STUDENTS AND MENAS: SITUATION AND -

Relevant Market/ Region Commercial Transaction Rates

Last Updated: 31, May 2021 You can find details about changes to our rates and fees and when they will apply on our Policy Updates Page. You can also view these changes by clicking ‘Legal’ at the bottom of any web-page and then selecting ‘Policy Updates’. Domestic: A transaction occurring when both the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of the same market. International: A transaction occurring when the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of different markets. Certain markets are grouped together when calculating international transaction rates. For a listing of our groupings, please access our Market/Region Grouping Table. Market Code Table: We may refer to two-letter market codes throughout our fee pages. For a complete listing of PayPal market codes, please access our Market Code Table. Relevant Market/ Region Rates published below apply to PayPal accounts of residents of the following market/region: Market/Region list Taiwan (TW) Commercial Transaction Rates When you buy or sell goods or services, make any other commercial type of transaction, send or receive a charity donation or receive a payment when you “request money” using PayPal, we call that a “commercial transaction”. Receiving international transactions Where sender’s market/region is Rate Outside of Taiwan (TW) Commercial Transactions 4.40% + fixed fee Fixed fee for commercial transactions (based on currency received) Currency Fee Australian dollar 0.30 AUD Brazilian real 0.60 BRL Canadian -

Ravn, Troels (S)

Ravn, Troels (S) Member of the Folketing, The Social Democratic Party Primary school principal Dalgårdsvej 124 6600 Vejen Mobile phone: +45 6162 4783 Email: [email protected] Troels Ravn, born August 2nd 1961 in Bryrup, son of insurance agent Svend Ravn and housewife Anne Lise Ravn. Married to Gitte Heise Ravn. Member period Member of the Folketing for The Social Democratic Party in South Jutland greater constituency from January 12th 2016. Member of the Folketing for The Social Democratic Party in South Jutland greater constituency, 15. September 2011 – 18. June 2015. Member of the Folketing for The Social Democratic Party in Ribe County constituency, 8. February 2005 – 13. November 2007. Temporary Member of the Folketing for The Social Democratic Party in South Jutland greater constituency (substitute for Lise von Seelen), 29. October 2008 – 20. November 2008. Candidate for The Social Democratic Party in Vejen nomination district from 2007. Candidate for The Social Democratic Party in Grindsted nomination district, 20032007. Parliamentary career Spokesman on fiscal affairs from 2019. Supervisor of the Library of the Danish Parliament from 2019. Chairman of the Social Affairs Committee, 20162019. Chairman of the South Schleswig Committee, 20142015. Spokesman on cultural affairs and media, 20142015. Chairman of the Immigration and Integration Affairs Committee, 20132015. Supervisor of the Library of the Danish Parliament, 20112015. Spokesman on children and education, 20112014. Member of the Children's and Education Committee, of the Cultural Affairs Committee, of the Gender Equality Committee and of the Rural Districts and Islands Committee, 20112015. Vicechairman of the Science and Technology Committee, 2007. -

Searching for Viking Age Fortresses with Automatic Landscape Classification and Feature Detection

remote sensing Article Searching for Viking Age Fortresses with Automatic Landscape Classification and Feature Detection David Stott 1,2, Søren Munch Kristiansen 2,3,* and Søren Michael Sindbæk 3 1 Department of Archaeological Science and Conservation, Moesgaard Museum, Moesgård Allé 20, 8270 Højbjerg, Denmark 2 Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, Høegh-Guldbergs Gade 2, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark 3 Center for Urban Network Evolutions (UrbNet), Aarhus University, Moesgård Allé 20, 8270 Højbjerg, Denmark * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +45-2338-2424 Received: 19 June 2019; Accepted: 25 July 2019; Published: 12 August 2019 Abstract: Across the world, cultural heritage is eradicated at an unprecedented rate by development, agriculture, and natural erosion. Remote sensing using airborne and satellite sensors is an essential tool for rapidly investigating human traces over large surfaces of our planet, but even large monumental structures may be visible as only faint indications on the surface. In this paper, we demonstrate the utility of a machine learning approach using airborne laser scanning data to address a “needle-in-a-haystack” problem, which involves the search for remnants of Viking ring fortresses throughout Denmark. First ring detection was applied using the Hough circle transformations and template matching, which detected 202,048 circular features in Denmark. This was reduced to 199 candidate sites by using their geometric properties and the application of machine learning techniques to classify the cultural and topographic context of the features. Two of these near perfectly circular features are convincing candidates for Viking Age fortresses, and two are candidates for either glacial landscape features or simple meteor craters. -

Vejle Sports Academy

VEJLE SPORTS ACADEMY What’s it about? Our former international students emphasize that you: • Improve your language skills • Work on your competencies • Clarify your wishes for the future • Get interesting lectures and classes • Make friends of a lifetime • Build up your shape • Learn about Danish society and culture • Can become a sports instructor • Develop personal and social skills • Reload your batteries for further education • Face exciting challenges of a life time Page 2 And a lot more ... Welcome to Vejle Sports Academy Personal development and social life Danish Sports Academy We believe that sports can be a part of your personal Vejle Sports Academy is a Danish Folk High School. development. To us, sports is also one of the best ways of We offer non-formal education as a boarding spending time together, and it is an icebreaker when getting school where you sleep, eat, study and spend your spare to know people. time at the school with the rest of the 115 school students. Sport takes up much of the lessons, but discussions, crea- The length of a typical stay is 4 months. tivity and general knowledge subjects are also an important About 1/5 of the school students come from other part of the curriculum. And after hours we get together for countries than Denmark. many social activities. Prepare for challenges, sweat, teamwork, social activity and an experience for life. We look forward to seeing you! Ole Damgaard, Headmaster Page 3 At Vejle Sports Academy you can put together your stay according to your dreams and your calendar. -

Relevant Market/ Region Commercial Transaction Rates

Last Updated: 31, May 2021 You can find details about changes to our rates and fees and when they will apply on our Policy Updates Page. You can also view these changes by clicking ‘Legal’ at the bottom of any web-page and then selecting ‘Policy Updates’. Domestic: A transaction occurring when both the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of the same market. International: A transaction occurring when the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of different markets. Certain markets are grouped together when calculating international transaction rates. For a listing of our groupings, please access our Market/Region Grouping Table. Market Code Table: We may refer to two-letter market codes throughout our fee pages. For a complete listing of PayPal market codes, please access our Market Code Table. Relevant Market/ Region Rates published below apply to PayPal accounts of residents of the following market/region: Market/Region list Vietnam (VN) Commercial Transaction Rates When you buy or sell goods or services, make any other commercial type of transaction, send or receive a charity donation or receive a payment when you “request money” using PayPal, we call that a “commercial transaction”. Receiving international transactions Where sender’s market/region is Rate Outside of Vietnam (VN) Commercial Transactions 4.40% + fixed fee Fixed fee for commercial transactions (based on currency received) Currency Fee Australian dollar 0.30 AUD Brazilian real 0.60 BRL Canadian dollar -

Boxing Edition

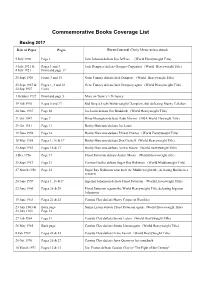

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

International Study Guide Series

International Study Guide Series Denmark Montana 4-H Center for Youth Development, Montana State University Extension 1 MONTANA 4‐H INTERNATIONAL STUDY SERIES The 4‐H program has had an active role in Montana youth and volunteer development for almost 100 years. It is most well‐known for its local emphasis, but 4‐H does exist in a broader context ‐ from a local to an international level. The ultimate objective of 4‐H international and cross‐cultural programming is "peace through understanding." Extension Service efforts help young people achieve this overall goal by encouraging them to: realize the significance of global interdependency; develop positive cross‐cultural attitudes and skills that enhance understanding and acceptance of people from other ethnic, social, or economic backgrounds; appreciate for the similarities and differences among all people; assume global citizenship responsibilities; develop an understanding of the values and attitudes of Americans. Since the introduction of international 4‐H opportunities in 1948, the Montana 4‐H program has been committed to the goal of global awareness and increasing cross‐cultural understanding. Cultures are becoming more dependent upon one another for goods, services, food, and fiber. Montana's role in the international trade arena is ever‐growing. The acquisition of increased knowledge of the markets and the people who influence those markets is crucial to the residents of our state. The 4‐H international programs are coordinated by States’ 4‐H International Exchange Programs (S4‐H) for participating state 4‐H Youth Development programs. Funding for the exchange programs is provided on the state level by the Montana 4‐H Foundation through private donations and contributions. -

Villum Fonden

VILLUM FONDEN Technical and Scientific Research Project title Organisation Department Applicant Amount Integrated Molecular Plasmon Upconverter for Lowcost, Scalable, and Efficient Organic Photovoltaics (IMPULSE–OPV) University of Southern Denmark The Mads Clausen Institute Jonas Sandby Lissau kr. 1.751.450 Quantum Plasmonics: The quantum realm of metal nanostructures and enhanced lightmatter interactions University of Southern Denmark The Mads Clausen Institute N. Asger Mortensen kr. 39.898.404 Endowment for Niels Bohr International Academy University of Copenhagen Niels Bohr International Academy Poul Henrik Damgaard kr. 20.000.000 Unraveling the complex and prebiotic chemistry of starforming regions University of Copenhagen Niels Bohr Institute Lars E. Kristensen kr. 9.368.760 STING: Studying Transients In the Nuclei of Galaxies University of Copenhagen Niels Bohr Institute Georgios Leloudas kr. 9.906.646 Deciphering Cosmic Neutrinos with MultiMessenger Astronomy University of Copenhagen Niels Bohr Institute Markus Ahlers kr. 7.350.000 Superradiant atomic clock with continuous interrogation University of Copenhagen Niels Bohr Institute Jan W. Thomsen kr. 1.684.029 Physics of the unexpected: Understanding tipping points in natural systems University of Copenhagen Niels Bohr Institute Peter Ditlevsen kr. 1.558.019 Persistent homology as a new tool to understand structural phase transitions University of Copenhagen Niels Bohr Institute Kell Mortensen kr. 1.947.923 Explosive origin of cosmic elements University of Copenhagen Niels Bohr Institute Jens Hjorth kr. 39.999.798 IceFlow University of Copenhagen Niels Bohr Institute Dorthe DahlJensen kr. 39.336.610 Pushing exploration of Human Evolution “Backward”, by Palaeoproteomics University of Copenhagen Natural History Museum of Denmark Enrico Cappellini kr. -

Ranking As of Sept. 10, 2012

Ranking as of Sept. 10, 2012 HEAVYWEIGHT JR. HEAVYWEIGHT LT. HEAVYWEIGHT (Over 201 lbs.)(Over 91,17 kgs) (200 lbs.)(90,72 kgs) (175 lbs.)(79,38 kgs) CHAMPION CHAMPION CHAMPION WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO (Sup Champ) UKR MARCO HUCK GER NATHAN CLEVERLY GB OLA AFOLABI (Interim) GB 1. Denis Boytsov RUS 1. BJ Flores USA 1. Robin Krasniqi (International) GER 2. Seth Mitchell (NABO) USA 2. Aleksandr Alekseev RUS 2. Braimah Kamoko (WBO Africa) GHA 3. David Haye (International) GB 3. Mateusz Masternak POL 3. Juergen Braehmer GER 4. Alexander Ustinov RUS 4. Nenad Borovcanin (WBO Europe Int.) SER 4. Dustin Dirks GER 5. Chris Arreola USA 5. Nuri Seferi (WBO Europe) ALB 5. Eduard Gutknecht GER 6. Carlos Takam (WBO Africa) CAM 6. Pawel Kolodziej POL 6. Bernard Hopkins USA 7. Luis Ortiz (Latino) CUB 7. Steve Cunningham USA 7. Vyacheslav Uzelkov (Int-Cont) UKR 8. Tyson Fury (Int-Cont) GB 8. Firat Arslan GER 8. Andrzej Fonfara POL 9. Robert Helenius FIN 9. Lateef Kayode NIG 9. Cornelius White USA 10. Francesco Pianeta ITA 10. Laudelino Barros (Latino) BRA 10. Karo Murat GER 11. Shane Cameron (Asia-Pac) (Oriental) NZ 11. Krzysztof Glowacki (Int-Cont) POL 11. Denis Simcic SVN 12. Sherman Williams (China)(Asia-Pac Int) BAH 12. Tony Conquest (International) GB 12. Jackson Junior (Latino) BRA 13. Kubrat Pulev BUL 13. Rakhim Chakhkiev RUS 13. Isaac Chilemba MAL 14. Joe Hanks USA 14. Danny Green AUST 14. Tony Bellew GB 15. Mariusz Wach POL 15. Agron Dzila SWI 15. Eleider Alvarez (NABO) COL CHAMPIONS CHAMPIONS CHAMPIONS WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO WBA GUILLERMO JONES WBA BEIBUT SHUMENOV WBA WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO IBF YOAN PABLO HERNANDEZ IBF TAVORIS CLOUD IBF VITALI KLITSCHKO WBC KRZYSZTOF WLODARCZYK WBC CHAD DAWSON WBC SUP. -

Open Call Kolding Den 14

Open Call Kolding den 14. november 2017 Art projects for the Triangle Festival 2019 From 23 august to 1 September 2019 For the last couple of years, art has played a bigger and bigger role in the Triangle Festival. We would like to do even more to visualize the art experiences in our festival and make them more accessible to our audience. Therefore, we have chosen to show art in seven Art Zones. Each Art Zone has its own aesthetics and history - places where people meet, hang out or pass by. The seven art zones have different hosts, and they will each get different expressions that appeal to different people. We are looking for art projects that work site-specific and who will explore the festival theme ’MOVE’. We wish that some of the projects involve the audience, but it is not a requirement for all projects. The Seven Art Zones The Manor House Sønderskov offers a special aesthetic experience with historical depth. The beautiful frames invite art projects that awaken curiosity. The Town Square ’Gravene’ The square is located in the part of Haderslev, which houses the oldest central districts near Haderslev Cathedral. The place is full of history and invites to art projects that experiment with the possibilities of the place. The Library Park The place is a recreational city oasis for the citizens. It has been created each year since 2016 in front of Kolding Library for a few weeks in late summer. Invites projects that surprise and experiment with creating new rooms in the city. The Mental Hospital (Teglgårdsparken) The former mental hospital in the city of Middelfart invites to a cultural day focused on psychiatry in fascinating historical frameworks. -

Coping with the International Financial Crisis at the National Level in a European Context

European Commission Directorate-General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union Coping with the international financial crisis at the national level in a European context Impact and financial sector policy responses in 2008 – 2015 This document has been prepared by the Directorate-General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union (DG FISMA). This document is a European Commission staff working document for information purposes. It does not represent an official position of the Commission on this issue, nor does it anticipate such a position. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained in this publication, or for any errors which, despite careful preparation and checking, may appear. ABBREVIATIONS Countries and regions EU: European Union EA: Euro area CEE: Central and Eastern Europe MS: Member State BE: Belgium BG: Bulgaria CZ: Czech Republic DK: Denmark DE: Germany EE: Estonia IE: Ireland EL: Greece ES: Spain FR: France HR: Croatia IT: Italy CY: Cyprus LV: Latvia LT: Lithuania LU: Luxembourg HU: Hungary MT: Malta NL: The Netherlands AT: Austria PL: Poland PT: Portugal RO: Romania SI: Slovenia SK: Slovakia FI: Finland SE Sweden UK: United Kingdom JP: Japan US: United States of America Institutions EBA: European Banking Authority EBRD: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EC: European Commission ECB: European Central Bank Fed: Federal Reserve, US IMF: International Monetary Fund OECD: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development v Graphs/Tables/Units bn: Billion bp. /bps: Basis point / points lhs: Left hand scale mn: Million pp.