One-Inch Type C Video: the Broadcast Standard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sony Recorder

Sony Recorder www.ctlny.com 24 All prices subject to change DVCAM, J-Series, Portable & Betacam Recorders DVCAM Recorders J-Series Betacam Recorders SP Betacam Recorders Sony Model# DSR1500A Sony Model# J1/901 Sony Model# PVW2600 Sales price $5,680.08 Sales price $5,735.80 Sales price $12,183.36 Editing recorder also play Beta/SP/SX Player w/ Betacam SP Video Editing DVCPRO,SDI-YUV Component Output Player with TBC & TC optional 8-3/8 x 5-1/8 x 16-5/8 16-7/8 x 7-5/8 x 19-3/8 Model # List Sales price Model # List Sales price Model # List Sales price DSR1500A $7,245.00 $5,680.08 J1/901 $6,025.00 $5,735.80 PVW2600 $15,540.00 $12,183.3 Editing recorder also play DVCPRO,SDI-YUV optional Beta/SP/SX Player w/ Component Output Betacam SP Video Editing Player with TBC & TC 6 DSR1600 $6,975.00 $5,468.40 J1/902 $7,050.00 $6,711.60 PVW2650 $22,089.00 $17,317.7 Edit Player w/ DVCPRO playback, RS-422 & DV Output Beta/SP/SX Editing Player w/ SDI Output Betacam SP Editing Player w. Dynamic Tracking, TBC & TC8 DSR1800 $9,970.00 $7,816.48 J2/901 $10,175.00 $9,686.60 PVW2800 $23,199.00 $18,188.0 Edit Recorder w/DVCPRO playback,RS422 & DV Output IMX/SP/SX Editing Player w/ Component Output Betacam SP Video Editing Recorder with TBC & TC 2 DSR2000 $15,750.00 $13,229.4 J2/902 $11,400.00 $10,852.8 UVW1200 $6,634.00 $5,572.56 DVCAM/DVCPRO Recorder w/Motion Control,SDI/RS422 4 IMX/SP/SX Editing Player w/ SDI Output 0 Betacam Player w/ RGB & Auto Repeat Function DSR2000P $1,770.00 $14,868.0 J3/901 $12,400.00 $11,804.8 UVW1400A $8,988.00 $7,549.92 PAL DVCAM/DVCPRO -

Minimum Charqe F25.00 Minimum Charqe €20.00

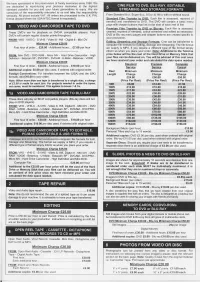

We have specialisedin the preservationof familymemories since 1988.We are dedicated to reproducing your precious memories to the highest standard possiblefor you and your future generationsto enjoy. We are consciousof the responsibilityentrusted to us and take this responsibility seriously.All prices includeVAT. All ordersare processedto the U.K. PAL FromStandard Bmm, Super Bmm, 9.5mm & 16mmwith or withoutsound. format(except where the USA NTSCformat is requested). Standard Film Transfer to DVD: Each film is assessed, repaired(if needed) and transferredto DVD. The DVD will contain a basic menu pagewith chaplerbuttons that link to the startof each reel of film. Premium Film Transfer to DVD or Blu-rav: Each film is assessed, These DVD's are for playback on DVD-R compatible players. Your cleaned,repaired (if needed),colour corrected and edited as necessary. DVD'swill containregular chapter points throughout. DVD or Blu-raymenu pages and chapterbuttons are createdspecific to your production. FROM:VHS -VHS-C - S-VHS-VideoB - HiB- DigitalB- MiniDV Editinq. Streaminq and Storaqe Formats: Cine can be transferredto MinimumCharqe €20.00 computerfile formatsfor Editing,Storage and Streaming.The file format Firsthour of order....€20.00 - Additionalhours.... €7.00 per hour we supply is MP4, if you require a differenttype of file format simply informus when you place your order. Note: Additional to the Telecine price below will be the the Hard Drive Memory FROM:Mini DVD - DVD RAM - MicroMV - Hard DriveCamcorder - High cost of or Stick that your Definition- BelacamSP - DVCPRO- DVCAM- U-Matic- Betamax- V2000. files can be delivered on. You will be advised of this cost once we have received your order and calculated the data space needed. -

Professio Nal VHS Videotape C I Ea N E R/L N S Pe Cto R/R Ew I N D E R

Professio nal VHS Videotape C I ea n e r/l n s pe cto r/R ew i n d e r Tzpeflle* Makes Them Last Longer... Finds Damage So You Can... Play Better! Fix Them,., Reduces VCR Maintenance! Retire Them.,. or Replace Them! uuww,rtico.GCDm Researctr Technology Products for Videotape Care from l-t-fi Interrrational For All Professional \ftlS \ LIBRARIES. Give your patrons the quality they. EDUCATIONAL MEDIA & TECHNOLOGY CENTERS. PUBLIC Extend the useful life olyour tapes. Add newtitles Ertend the usefullife of your tapes. Provide your students 0"""r". tnrn replacements".Be confident you are circulating and teachers with an exira margin of quality. Circulate c/ean r"tf't"t gooO tapbs. Verify patron complaints imm€diately' tapes. lnspectihe quality ol tapes. Why spend hours onty are damaged and remove them from tebiously viewing tapes io find the damaged ones? kn6vilwnicn'tapes TapeChek models are fasf and simplelo TapeOhbk doeslt for you quickly and automatically! circulation, operate...just insert the tape and press a button! Tapzfhek 400 Series VHS Videotape Cleaner/lnspectors TOP.OF.THE.LINE MODELS 480 AND 490 INCLUDE 3-CHANNEL oEreCrtON SvSTEM, COMPREHENSIVE TAPE INFORMATION DISPLAY AND PRINTER INTERFACE . Tape lnformation Display"'provides . Cleans...specially formulated cleaning tissue gently Comprehensive defect data and tape length, plus diagnostics wioes awav dirt anO other debris from the tape. Eliminates reoorts'of information (Displays 1 through 5). temporary'dropouts and helps to keep VCRs clean' and setup entry of date, tape' . Polishes...sapphire burnisher removes loose oxide, the . Data Entry Keypad...permits number for printed reports. -

Ampex GS-OOS-22639 Magnetic Tape Recorders

. ~ . / , . '. i I. Authorized Federal Supply Schedule Price List FSC Group 74 Pam III and II Contractor Ampex Audio, Inc. Contract No. GS-OOS·22639 Period July 23, 1959 through 'June 30, 1960 General Services Administration Federal Supply Service GSA Distribution Code 87 GS-OO -22&39 • AUTHORIZED FEDERAL SUPPLY SCHEDULE AMPEX AUDIO, INC . 1020 KIFER ROAD SUNNYVALE, CALIFORNIA 7 If the Ampex Audio Deale r has delivered the equipment from his stock the serial numbers HAl of units delivered and a receipt for delivery REC will accompany the original Government UNf Purchase Order sent to Ampex Audi o, Inc. PLA 8 m pe x Audio, Inc. will invoice to Government Ag nc y on all purchases under this contract. Determine item desired from ihis catalog. Dea l r s lis ted here in a r e not authorized to mod Lfy any portion of this contract. 2 The Government Agency may place an order STE with the nearest Ampex Audio Franchised 9 If a ny eq uipment is r eceived in damaged condi REe Dealer, and address the order as follows : ti on , the Government Agency will immediately UNf advise Ampex Audio, Inc., Sunnyvale, Calif. PLA AMPEX AUDIO, INC. by collec t wi re, indicating Purchase Order John Doe, Dealor numbe r, s erIal number of item (if any). extent Street Add ,ou of damage and when items may be inspected. City, Stale Note: For names of Deale rs in your area, write to Government Sales Department, 10 UNIT PRICE - - Eacb f. o. b. destination Con Ampex Audio, Inc., Sunnyvale, Cal if. -

Betacam Sp One-Piece Camcorder (Ntsc)

BETACAM SP ONE-PIECE CAMCORDER (NTSC) . Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 2. HISTORY OF FIELD SHOOTING 2-1. Early Days of ENG 2-2. The Introduction of BetacamTM System 2-3. The Introduction of Betacam SP System 2-4. The Introduction of BVW-200 One-piece Camcorder 3. INNOVATION IN THE BVW-200/300/400 3-1. One-piece Camcorder Internal Layout 3-2. VTR Mechanical Features 3-2-1. Small drum design 3-2-2. Miniaturized tape transport mechanism 3-3. VTR Electronic Features 3-3-1. Plug-in PC board construction 3-3-2. Software servo control IC 3-3-3. Serial interface among CPU's 3-3-4. High density circuit board 3-3-5. LCD multiple displays 3.4. Camera Technical Features 3-4-1. Camera head construction 3-4-2. Advanced Sony's CCD technology 4. EASY OPERATION 4-1. Refined Ergonomics 4-2. Rain and Dust-proof Structure 4-3. Quick Start Viewfinder 4-3-1. Optical/CRT 4-3-2. Viewfinder mechanism 4-3-3. Operational facilities 4-4. Detachable Microphone 4-5. Tally Lamp 4-6. Battery for Time Code Back-up 4-7. Other Operational Facilities 4-7-1. VTR section 4-7-2. Camera section 4-7-3. Exclusive features for BVW-400 5. EASY MAINTENANCE AND ADVANCED SERVICEABILITY 6. EXCELLENT EXPANDABILITY 7. EXPLANATION OF BVW-200/300/400 FUNCTION KEYS AND BUTTONS 8. SPECIFICATIONS Before delving into the technical and operational issues, let us briefly review the history of news coverage and Single Camera Production in the television industry. 2.1. -

Videotape: Hardware, History and Applications

VIDEOTAPE: HARDWARE, HISTORY AND APPLICATIONS Carole 0. Bell and Patricla A. Maetick In recent years, folklorists have begun to raco~nlzeand udllze visu4trCdir ao reeearch and communicative toolr. In 1967, Ralph Rinzler's film work was shown at the Amcrican Folklore Society meetings. Subsequently, films by Bess Lomax Hawes, William Ferris and Carl Fleiechhauer have demonstrated the applicability and importance of visual communication to the study of folklore. In general, however, folklorists have been reluctant to adopt this form of communication. They admire the research footage or fiaished filmic products of their colleagues, but ignore the implications of such work for future remearch into various aspects of traditional humur behavior, Videotape, a relatively new visual medium, ha^ contributed to an increaeine senee of urgency among visually-oriented social scientists. Technical improvements in recent years allow its consideration as an invaluable tool for folklore research. Portable videotape equipment was widely available by 1970, the year when standardization of this hardware became a reality. Greater numbers of people began to handle the equipment and ta rhare with one another the results of their efforts. With the increaoing availability of videotape recording system came the inevitable camparisens with film. Both are multi-media syetew utilizing two channels of trans- mission and reception of information, hopefully in an integrated manner. Yet, they are not the same. The initial distinction is the quality of realneee which video displays. Somehow, it is easier to reopond to the image captured on videotape; the content of the tape meem less removed from the present than that of film. -

EMERGENCY REGULATION TEXT Patient Electronic Property

DEPARTMENT OF STATE HOSPITALS EMERGENCY REGULATION TEXT Patient Electronic Property California Code of Regulations Title 9. Rehabilitative and Developmental Services Division 1. Department of Mental Health Chapter 16. State Hospital Operations Article 3. Safety and Security Amend section 4350, title 9, California Code of Regulations to read as follows: [Note: Set forth is the amendments to the proposed emergency regulatory language. The amendments are shown in underline to indicate additions and strikeout to indicate deletions from the existing regulatory text.] § 4350. Contraband Electronic Devices with Communication and Internet Capabilities. (a) Except as provided in subsection (d), patients are prohibited from having personal access to, possession, or on-site storage of the following items: (1) Electronic devices with the capability to connect to a wired (for example, Ethernet, Plain Old Telephone Service (POTS), Fiber Optic) and/or a wireless (for example, Bluetooth, Cellular, Wi-Fi [802.11a/b/g/n], WiMAX) communications network to send and/or receive information including, but not limited to, the following: (A) Desktop computers; laptop computers; tablets; single-board computers or motherboards such as “Raspberry Pi;” cellular or satellite phones; personal digital assistant (PDA); graphing calculators; and satellite, shortwave, CB and GPS radios. (B) Devices without native capabilities that can be modified for network communication. The modification may or may not be supported by the product vendor and may be a hardware and/or software configuration change. (2) Digital media recording devices, including but not limited to CD, DVD, Blu-Ray burners. Page 2 (3) Voice or visual recording devices in any format. (4) Items capable of patient-accessible memory storage, including but not limited to: (A) Any device capable of accessible digital memory or remote memory access. -

Videotape in Civil Cases Guy O

Hastings Law Journal Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 2 1-1972 Videotape in Civil Cases Guy O. Kornblum Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Guy O. Kornblum, Videotape in Civil Cases, 24 Hastings L.J. 9 (1972). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol24/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. Videotape in Civil Cases By GuY 0. KORNBLUM* OUR judicial system is accused of yielding under the strain of its own inefficiency. There are charges that our litigation machinery is ineffective in processing lawsuits and is irreparably broken down. Proposals for reform are never-ending. For the most part, these pro- posals are directed towards making our courts modem and efficient, thereby reducing the backlog of cases.' Certain of these proposals have raised far-reaching constitutional issues: for example, whether there should be no right to a jury in a civil trial2 and whether a con- viction based on a non-unanimous verdict' of a less than twelve-person * A.B., 1961, Indiana University; J.D., 1966, University of California, Hastings College of the Law; Associate Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law; Co-Director of National College of Advocacy, 1970-72; Member, California and Indiana Bars. The author is grateful to Christine Helwick, Member, Third Year Class, Hastings College of the Law, for her research assistance and to Paul Rush, Producer/Director, University of California Television Office, Berkeley, for his assistance in gathering technical information. -

Magnetic Tape Storage and Handling a Guide for Libraries and Archives

Magnetic Tape Storage and Handling Guide Magnetic Tape Storage and Handling A Guide for Libraries and Archives June 1995 The Commission on Preservation and Access is a private, nonprofit organization acting on behalf of the nation’s libraries, archives, and universities to develop and encourage collaborative strategies for preserving and providing access to the accumulated human record. Additional copies are available for $10.00 from the Commission on Preservation and Access, 1400 16th St., NW, Ste. 740, Washington, DC 20036-2217. Orders must be prepaid, with checks in U.S. funds made payable to “The Commission on Preservation and Access.” This paper has been submitted to the ERIC Clearinghouse on Information Resources. The paper in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials ANSI Z39.48-1992. ISBN 1-887334-40-8 No part of this publication may be reproduced or transcribed in any form without permission of the publisher. Requests for reproduction for noncommercial purposes, including educational advancement, private study, or research will be granted. Full credit must be given to the author, the Commission on Preservation and Access, and the National Media Laboratory. Sale or use for profit of any part of this document is prohibited by law. Page i Magnetic Tape Storage and Handling Guide Magnetic Tape Storage and Handling A Guide for Libraries and Archives by Dr. John W. C. Van Bogart Principal Investigator, Media Stability Studies National Media Laboratory Published by The Commission on Preservation and Access 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 740 Washington, DC 20036-2217 and National Media Laboratory Building 235-1N-17 St. -

Glossary of Digital Video Terms

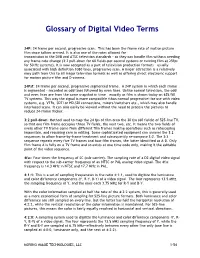

Glossary of Digital Video Terms 24P: 24 frame per second, progressive scan. This has been the frame rate of motion picture film since talkies arrived. It is also one of the rates allowed for transmission in the DVB and ATSC television standards – so they can handle film without needing any frame-rate change (3:2 pull-down for 60 fields-per-second systems or running film at 25fps for 50 Hz systems). It is now accepted as a part of television production formats – usually associated with high definition 1080 lines, progressive scan. A major attraction is a relatively easy path from this to all major television formats as well as offering direct electronic support for motion picture film and D-cinema. 24Psf: 24 frame per second, progressive segmented frame. A 24P system in which each frame is segmented – recorded as odd lines followed by even lines. Unlike normal television, the odd and even lines are from the same snapshot in time – exactly as film is shown today on 625/50 TV systems. This way the signal is more compatible (than normal progressive) for use with video systems, e.g. VTRs, SDTI or HD-SDI connections, mixers/switchers etc., which may also handle interlaced scans. It can also easily be viewed without the need to process the pictures to reduce 24-frame flicker. 3:2 pull-down: Method used to map the 24 fps of film onto the 30 fps (60 fields) of 525-line TV, so that one film frame occupies three TV fields, the next two, etc. It means the two fields of every other TV frame come from different film frames making operations such as rotoscoping impossible, and requiring care in editing. -

SMPTE Type C Helical-Scan Recording Format by DAVID K

SMPTE Type C Helical-Scan Recording Format By DAVID K. FIBUSH About two years ago there was little prospect that a 1-in helical-scan videotape recorded marily to eliminate the need to review all on one manufacturer’s machine could ever be played back on another manufacturer’s aspects of the format each time a change VTR. In a single year, however, this situation has changed and the S M P T E Standards is made. Typically, the format documents Committee has approved the basic format documents for high-quality I-in helical-scan include a document showing record loca- VTRs capable of interchanging tapes. Topics covered in detail in the paper include: the tions on the tape, a mechanical configura- process of developing a standard, with a list of the relevant ANSI and S M P T E tion document, and a number of electrical documents; helical video format parameters, with definitions and criteria for their parameter documcnts for video, audio, selection; location of tape tracks; video and sync records, with sources and magnitudes control track, ctc. Many pcoplc are famil- of various time-base errors; limitation of vertical-interval dropout; the requirement for iar with the record location drawing as this six heads; the contraints of video track straightness and longitudinal track dimensions; information is widely publicized to show audio and control-track recording; and video signal processing. I t is expected that the the users the available channels and some new SMPTE Type C format will provide a practical solution to the users’ requirements of the features of the VTR. -

Capturing Video from U-Matic, Betacam SP, Digibeta and Dvcpro

Capturing Video from U-matic, Betacam SP, Digibeta and DVCPro Station Setup (When switching formats) 1. Power Up All Equipment a. Restart computer b. Check vRecord settings (“vrecord -e”), then open vRecord (“vrecord -p”) c. Check Blackmagic Desktop Video settings, then open Blackmagic Media Express d. Clean the deck e. Play a test tape until signal chain and sync are complete 2. Connect the Signal Chain a. Deck → Monitor b. Deck → TBC → Capture Card* → Monitor c. TBC → Video Scope d. Deck → Audio Mixer** → Capture Card → Audio Scope e. Deck (Remote) → Capture Card (Remote) 3. Synchronize the Signals a. Sync/Blackburst Generator → All equipment via Ext Sync/Ref/Gen Lock b. Rewind test tape c. Clean the deck Video Capture (Daily Workflow) 1. Power Up All Equipment a. Restart computer (daily) b. Open vRecord (“vrecord -p”) and Blackmagic Media Express c. Clean the deck 2. Set Levels (for analog tapes only) a. Play Bars and Tone tape b. Bring bars within broadcast range (Black, Luma, Chroma, Hue) c. Use audio mixer to set audio level (approximately -18 in Blackmagic) d. Clean the deck e. Play tape to be captured f. Adjust levels to content of tape g. Pack tape (fast forward to the tail, then back to the head of the tape) 3. Capture the File a. Clean the deck b. Insert tape to be captured c. Switch on deck’s remote (if connected to the capture card remote) d. Fill in the fields in Blackmagic for your file (“YourFileName_Try1”) e. Hit “Capture” in Blackmagic to start, then spacebar to activate remote on deck f.