Videotape in Civil Cases Guy O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Professio Nal VHS Videotape C I Ea N E R/L N S Pe Cto R/R Ew I N D E R

Professio nal VHS Videotape C I ea n e r/l n s pe cto r/R ew i n d e r Tzpeflle* Makes Them Last Longer... Finds Damage So You Can... Play Better! Fix Them,., Reduces VCR Maintenance! Retire Them.,. or Replace Them! uuww,rtico.GCDm Researctr Technology Products for Videotape Care from l-t-fi Interrrational For All Professional \ftlS \ LIBRARIES. Give your patrons the quality they. EDUCATIONAL MEDIA & TECHNOLOGY CENTERS. PUBLIC Extend the useful life olyour tapes. Add newtitles Ertend the usefullife of your tapes. Provide your students 0"""r". tnrn replacements".Be confident you are circulating and teachers with an exira margin of quality. Circulate c/ean r"tf't"t gooO tapbs. Verify patron complaints imm€diately' tapes. lnspectihe quality ol tapes. Why spend hours onty are damaged and remove them from tebiously viewing tapes io find the damaged ones? kn6vilwnicn'tapes TapeChek models are fasf and simplelo TapeOhbk doeslt for you quickly and automatically! circulation, operate...just insert the tape and press a button! Tapzfhek 400 Series VHS Videotape Cleaner/lnspectors TOP.OF.THE.LINE MODELS 480 AND 490 INCLUDE 3-CHANNEL oEreCrtON SvSTEM, COMPREHENSIVE TAPE INFORMATION DISPLAY AND PRINTER INTERFACE . Tape lnformation Display"'provides . Cleans...specially formulated cleaning tissue gently Comprehensive defect data and tape length, plus diagnostics wioes awav dirt anO other debris from the tape. Eliminates reoorts'of information (Displays 1 through 5). temporary'dropouts and helps to keep VCRs clean' and setup entry of date, tape' . Polishes...sapphire burnisher removes loose oxide, the . Data Entry Keypad...permits number for printed reports. -

Videotape: Hardware, History and Applications

VIDEOTAPE: HARDWARE, HISTORY AND APPLICATIONS Carole 0. Bell and Patricla A. Maetick In recent years, folklorists have begun to raco~nlzeand udllze visu4trCdir ao reeearch and communicative toolr. In 1967, Ralph Rinzler's film work was shown at the Amcrican Folklore Society meetings. Subsequently, films by Bess Lomax Hawes, William Ferris and Carl Fleiechhauer have demonstrated the applicability and importance of visual communication to the study of folklore. In general, however, folklorists have been reluctant to adopt this form of communication. They admire the research footage or fiaished filmic products of their colleagues, but ignore the implications of such work for future remearch into various aspects of traditional humur behavior, Videotape, a relatively new visual medium, ha^ contributed to an increaeine senee of urgency among visually-oriented social scientists. Technical improvements in recent years allow its consideration as an invaluable tool for folklore research. Portable videotape equipment was widely available by 1970, the year when standardization of this hardware became a reality. Greater numbers of people began to handle the equipment and ta rhare with one another the results of their efforts. With the increaoing availability of videotape recording system came the inevitable camparisens with film. Both are multi-media syetew utilizing two channels of trans- mission and reception of information, hopefully in an integrated manner. Yet, they are not the same. The initial distinction is the quality of realneee which video displays. Somehow, it is easier to reopond to the image captured on videotape; the content of the tape meem less removed from the present than that of film. -

Magnetic Tape Storage and Handling a Guide for Libraries and Archives

Magnetic Tape Storage and Handling Guide Magnetic Tape Storage and Handling A Guide for Libraries and Archives June 1995 The Commission on Preservation and Access is a private, nonprofit organization acting on behalf of the nation’s libraries, archives, and universities to develop and encourage collaborative strategies for preserving and providing access to the accumulated human record. Additional copies are available for $10.00 from the Commission on Preservation and Access, 1400 16th St., NW, Ste. 740, Washington, DC 20036-2217. Orders must be prepaid, with checks in U.S. funds made payable to “The Commission on Preservation and Access.” This paper has been submitted to the ERIC Clearinghouse on Information Resources. The paper in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials ANSI Z39.48-1992. ISBN 1-887334-40-8 No part of this publication may be reproduced or transcribed in any form without permission of the publisher. Requests for reproduction for noncommercial purposes, including educational advancement, private study, or research will be granted. Full credit must be given to the author, the Commission on Preservation and Access, and the National Media Laboratory. Sale or use for profit of any part of this document is prohibited by law. Page i Magnetic Tape Storage and Handling Guide Magnetic Tape Storage and Handling A Guide for Libraries and Archives by Dr. John W. C. Van Bogart Principal Investigator, Media Stability Studies National Media Laboratory Published by The Commission on Preservation and Access 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 740 Washington, DC 20036-2217 and National Media Laboratory Building 235-1N-17 St. -

SMPTE Type C Helical-Scan Recording Format by DAVID K

SMPTE Type C Helical-Scan Recording Format By DAVID K. FIBUSH About two years ago there was little prospect that a 1-in helical-scan videotape recorded marily to eliminate the need to review all on one manufacturer’s machine could ever be played back on another manufacturer’s aspects of the format each time a change VTR. In a single year, however, this situation has changed and the S M P T E Standards is made. Typically, the format documents Committee has approved the basic format documents for high-quality I-in helical-scan include a document showing record loca- VTRs capable of interchanging tapes. Topics covered in detail in the paper include: the tions on the tape, a mechanical configura- process of developing a standard, with a list of the relevant ANSI and S M P T E tion document, and a number of electrical documents; helical video format parameters, with definitions and criteria for their parameter documcnts for video, audio, selection; location of tape tracks; video and sync records, with sources and magnitudes control track, ctc. Many pcoplc are famil- of various time-base errors; limitation of vertical-interval dropout; the requirement for iar with the record location drawing as this six heads; the contraints of video track straightness and longitudinal track dimensions; information is widely publicized to show audio and control-track recording; and video signal processing. I t is expected that the the users the available channels and some new SMPTE Type C format will provide a practical solution to the users’ requirements of the features of the VTR. -

TELEVISION and VIDEO PRESERVATION 1997: a Report on the Current State of American Television and Video Preservation Volume 1

ISBN: 0-8444-0946-4 [Note: This is a PDF version of the report, converted from an ASCII text version. It lacks footnote text and some of the tables. For more information, please contact Steve Leggett via email at "[email protected]"] TELEVISION AND VIDEO PRESERVATION 1997 A Report on the Current State of American Television and Video Preservation Volume 1 October 1997 REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS TELEVISION AND VIDEO PRESERVATION 1997 A Report on the Current State of American Television and Video Preservation Volume 1: Report Library of Congress Washington, D.C. October 1997 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Television and video preservation 1997: A report on the current state of American television and video preservation: report of the Librarian of Congress. p. cm. þThis report was written by William T. Murphy, assigned to the Library of Congress under an inter-agency agreement with the National Archives and Records Administration, effective October 1, 1995 to November 15, 1996"--T.p. verso. þSeptember 1997." Contents: v. 1. Report - ISBN 0-8444-0946-4 1. Television film--Preservation--United States. 2. Video tapes--Preservation--United States. I. Murphy, William Thomas II. Library of Congress. TR886.3 .T45 1997 778.59'7'0973--dc 21 97-31530 CIP Table of Contents List of Figures . Acknowledgements. Preface by James H. Billington, The Librarian of Congress . Executive Summary . 1. Introduction A. Origins of Study . B. Scope of Study . C. Fact-finding Process . D. Urgency. E. Earlier Efforts to Preserve Television . F. Major Issues . 2. The Materials and Their Preservation Needs A. -

Media Report – Videotape

Media Report – Videotape Year-month-day Object Identification Component Number Artist Title Date Tape Status Channel Information (If part of a multi-channel work, please state which channel this component relates to) Technical Specifications Duration of total recording on tape (including bars, titles, etc): Duration of artwork: ☐ Not Looped ☐ Looped; total number of cycles on tape: Tape Format: ☐ 1“ videotape ☐ 2“ videotape ☐ ¾“ U-matic ☐ ¾“ U-matic SP ☐ ½“ Open reel ☐ VHS ☐ Super-VHS ☐ VHS-C ☐ D2 ☐ Betamax ☐ Betacam ☐ Betacam SP ☐ Betacam SX ☐ Digital Betacam ☐ 8mm videotape ☐ Hi-8 ☐ Video8 ☐Digtial8 ☐MiniDV ☐ DVCAM ☐ HDCAM ☐HDCAM SR ☐ DVCPRO ☐DVCPRO-50 ☐DVCPRO HD ☐ Other: Tape Brand/Capacity: Recording Speed: SD - TV Standard: Audio (track configuration): ☐ SP (Standard Play) ☐ NTSC ☐ No sound ☐ Channel 1 ☐ LP (Long Play) ☐ PAL ☐ Mono ☐ Channel 2 ☐ SLP (Super Long Play) ☐ SECAM ☐ Stereo ☐ Channel 3 ☐ EP (Extended Play) ☐ Other: ☐ Unspecified ☐ Channel 4 ☐ EX (Extended Mode) Audio (encoding): ☐ Longitudinal ☐ (A)FM ☐ PCM Transfer from film: HD ☐ Noise Reduction: Dolby A / ☐ Copy from mm film Framerate: Dolby B / Dolby C Resolution: Color: Aspect Ratio: Time Code (TC): ☐ Black & White ☐ 4:3 ☐ Unknown ☐ Color ☐ 16:9 ☐ None ☐ Letterbox ☐ Yes, on: ☐ Anamorphic ☐ TC Track (VITC or LTC) ☐ Other: ☐ Audio Channel 1 ☐ Audio Channel 2 Recording Information Source Tape: AV Studio (Address, Contact): ☐ Whitney source; Component No. : ☐ Unknown ☐ Other Date of Recording: Transfer Supervisor: Signal Path: Cassette Label (only use for Artist-provided -

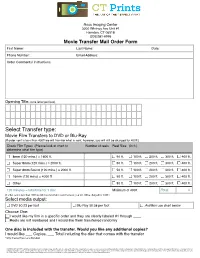

Movie Transfer Mail Order Form First Name: Last Name: Date

Ross Imaging Center 3000 Whitney Ave Unit #1 Hamden, CT 06518 (203)281-6996 Movie Transfer Mail Order Form First Name: Last Name: Date: Phone Number: Email Address: Order Comments/ Instructions: Opening Title: (one letter per box) Select Transfer type: Movie Film Transfers to DVD or Blu-Ray (If order sent is less than 400ft we will transfer what is sent, however, you will still be charged for 400ft.) Check Film Types (Please look at chart to Number of reels Reel Size (in ft.) determine what film type) 8mm (120 mins.) = 1600 ft. 50 ft. 100 ft. 200 ft. 300 ft. 400 ft. Super 8mm (120 mins.) = 2000 ft. 50 ft. 100 ft. 200 ft. 300 ft. 400 ft. Super 8mm Sound (120 mins.) = 2000 ft. 50 ft. 100 ft. 200 ft. 300 ft. 400 ft. 16mm (120 mins) = 4000 ft. 50 ft. 100 ft. 200 ft. 300 ft. 400 ft. Other 50 ft. 100 ft. 200 ft. 300 ft. 400 ft. 120 minutes = total time for 1 disc Minimum of 400ft Total: ft. (If order sent is less than 400ft we will transfer what is sent, however, you will still be charged for 400ft.) Select media output: DVD $0.23 per foot Blu-Ray $0.38 per foot .Avi/Mov use chart below Choose One: I would like my film in a specific order and they are clearly labeled #1 through ____ Reels are not numbered and I would like them transferred randomly One disc is included with the transfer. Would you like any additional copies? I would like ___ Copies, ___ Total including the disc that comes with the transfer *only master has outside label LIMITATION OF LIABILITY: Submitting any tangible or electronic media, image, data, file, card, disc, device, film, print, slide, or negative for any purpose, such as processing, printing, duplication, alteration, enlargement, storage, transmission, or other handling, constitutes an agreement that any loss or damage to it by our company, subsidiary or agents, even though by our negligence or other fault , will only entitle you to replacement with an equivalent quantity/size of unexposed photographic film or electronic media, and processing of the replacement media. -

A UNIVERSAL FORMAT for ARCHIVAL TAPE I, Proposal by Jim Wheeler December 1996

F A UNIVERSAL FORMAT FOR ARCHIVAL TAPE I, Proposal by Jim Wheeler December 1996 This year is the 40th anniversary of the Ampex Quadraples Videotape Recorder introduced in 1956. The quad format dominated for over 20 years, until it was finally replaced by the one inch type C format in 1978. Now, thousands of Quad tapes are sitting on archive shelves and many of them will probably die on the shelves. I. Introduction For most people in the TV Industry, the new videotape formats introduced at the National Association of Broadcasters Symposium in Las Vegas each year are exciting technological advances. But, for a person responsible for preserving the information recorded on videotapes, growth in the number of formats is a constant headache. Archives have collected vast numbers of videotapes in many different formats. While archivists wish to preserve this information, most institutions only have the resources to operate a few pieces of videotape equipment. Commonly, VHS and 314" U-Matic machines are found in smaller institutions, Betacam in a few others. Most do not have access to older broadcast equipment like Quad or I", and almost none have any of the newer digital equipment. The majority of these institutions are forced to reject acquisitions in formats they can not handle. If they do choose to keep these tapes, it is often without any realistic hope they will ever be able to see the images or preserve them. A national awareness of this problem is needed in the video industry. 11. Obsolete formats Figure 1 gives an idea of how many videotape formats exist in archives today. -

35Mm SLIDES, NEGATIVES OR PRINTS to DVD SLIDE SHOW

CAMCORDER HARD DRIVE VIDEO FILES TO DVD (N0 EDITING) 35mm SLIDES, NEGATIVES OR PRINTS MOTION PICTURE FILMS TO DVD AUDIO TAPE TRANSFERS TO CD TO DVD SLIDE SHOW State of the art transfers from movie film directly to DVD. CD transfers are available from audio cassettes, micro- Your originals are scanned, edited, sized and formatted Our ‘cold light’ capture process does not project your cassettes or open reel-to-reel tape. Only non-copyright- specifically for slide show presentation. This is our best film in the conventional sense, and yields superior re- ed, non-commercial audio will be transferred. Each tape quality service from analog source materials. sults. Your movie reels will be transferred in the order side is transferred as a single track on the CD. Audio you present them. All films are cleaned and lubricated, tape can be transferred to .mp3 files instead at the same $2.25 per original plus $60 set-up fee and small reels are spliced onto larger reels. Any notes price. and individual boxes are returned. All transfers are done CAMCORDER SD CARD VIDEO FILES TO DVD Titles $ 5.00 each with the least digital compression (60 minutes per DVD) each tape (up to 60 minutes) $30.00 (NO EDITING) Instrumental Music $15.00 for the best results. tapes longer than 60 minutes (from our music library) require additional CDs @ $30.00 per CD Individual track breaks $ 2.00 each DIGITAL STILL FILES TO DVD SLIDE SHOW Additional copies at time of transfer $ 9.00 each Your digital files from memory card, CD or scan made VIDEO TAPE TO TAPE DUPLICATIONS into a DVD slide show for viewing on TV or computer. -

A Review on the History and Application of Videotape Self- Confrontation in Therapy and Human Relations Training

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-1977 A Review on the History and Application of Videotape Self- Confrontation in Therapy and Human Relations Training Gerald F. Skillings Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy Commons Recommended Citation Skillings, Gerald F., "A Review on the History and Application of Videotape Self-Confrontation in Therapy and Human Relations Training" (1977). Master's Theses. 2198. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/2198 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A REVIEW ON THE HISTORY AND APPLICATION OF VIDEOTAPE SELF-CONFRONTATION IN THERAPY AND HUMAN RELATIONS TRAINING by Gerald F. Skillings A thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 1977 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". -

Ampex Tape-Type List

Ampex Tape-Type List Compiled by Scott Dorsey, NASA Langley Research Center This list started out as a response to the huge number of people asking questions about surplus instrumentation tape, developed into a short description on identifying Ampex tapes, and then developed into an attempt at categorizing all Ampex tapes made. This list is far from complete but is a good beginning: Note: All tapes backcoated unless otherwise indicated NB= Non-Backcoated LNER= Low Noise Extended Range LNHO= Low Noise High Output ----------------------------------------------- 021-- 1 mil rejected NB acetate tape (sold as Shamrock) (early 60s) 031-- 1.5 mil rejected mastering tape (maybe 406, 456, etc. depending on batch) (Was available in 2500' pancakes as well as 7" reels in 1983) 041-- 1 mil version of 031 in 7" only 051-- 0.5 mil rejected NB acetate tape (sold as Shamrock) (early 60s) 101-- Betamax half-inch videocassette (intro before 1978) 102-- VHS videocassette (late seventies) 142-- Helical 2" format video tape for VR-660/1500 (1962-?) 144-- Transverse scan video tape (1964-?) for quad-format machines 145-- Helical 2" formulated for VR-660/1500 video recorders (1966-?) backcoated 147-- A-format tape formulated for VR-7000 video recorders (1965-?) 148-- High Band 2" video tape (B&W) 161-- 1" videotape (1968-?) 163-- 1/2" helical scan industrial videotape (1968-?) 164-- 1/2" helical scan videotape for color use 165-- 1" videotape for IVC 600/800 series recorders 167-- U-Matic videocassette (replaced by 187/197) (late seventies, sold in 83) (Sometimes -

4Th Module Video Recording and Play Back

4th module Video recording and play back Sindhu K S Asst.Professor on Contract, Department of Computer Science L.F College Guruvayoor • Introduction: • Film …….only medium available for recording television pgms • Magnetic tape….used for sound • The greater the quantity of information carried by television signal demanded new studies • 1920 American Engineer ,Philo Taylor Farnsworth devised the television camera , an image dissector ,which converted the image captured in to an electrical signal • The pick-up tube is the main element governing the technical quality of the picture obtained by televisionb camera • The first electronic cameras using iconoscope tubes were characterized by very large lenses ,necessary to ensure enough light reached the pick-up tube • Charles Ginsburg led Ampex research team developing one of the first practical vudeo tape recorder(VTR). • In 1951 the first video tape recorder captured live images from television cameras by converting the camera’s electrical pulses and saving the information on to magnetic video tape • Video technology was first developed for CRT television systems. • VTR is 1st practical video tape recorder • VCR can do same • In 1980 and 1990 VCR removed by DVD players 4.1 basics of analog video tape recording principles • 4.1.1 Relationship of Tape and Bandwidth 4.2 Recording on magnetics tape and Reproduction Several inventions 1) In November 1951: The electronics division of Bing Crosby Enterprises , put on display a videotape recorder which produced black and white images Had 12 fixed recording heads. • In this recorder high speed head switching was employed along with 1”tape and 100 inches per second tape speed.