2018 Hawaii CHNA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May Special District Election Voters' Pamphlet May 16, 2017

Dear Multnomah County Voter: This Voters’ Pamphlet is for the May 2017 Special Election and is being mailed to all residential households in Multnomah County. Here are a few things you should know: • You can view your registration status at www.oregonvotes.gov/myvote. There you can check or update your voter registration or track your ballot. • Ballots will be mailed beginning on Wednesday, April 26, 2017. If you don’t receive your ballot by May 4, 2017, please call 503-988-3720 to request a replacement ballot Multnomah County • Not all the candidates or measures in this Voters’ Pamphlet will be on your ballot. Your residence address May Special determines those districts for which you may vote. Your official ballot will contain the candidates and issues which apply to your residence. District Election Voters’ Pamphlet • Not all candidates submitted information for the Voters’ Pamphlet so you may have candidates on your ballot that are not in the Voters’ Pamphlet. May 16, 2017 • Voted ballots MUST be received at any County _________________ elections office in Oregon or official drop site location by 8:00 PM, Tuesday, May 16, 2017 to be counted. Multilingual Voting • Information Inside This Voters’ Pamphlet is on our website: www.mcelections.org. Starting at 8:00 PM on election Información de votación en el night, preliminary election results will be posted on our interior del panfleto website and updated throughout the evening. Информация о процессе If you have any questions you can contact our office at: голосовании приведена внутри 503-988-3720. Bên Trong Có Các Thông Tin Về Sincerely, Việc Bỏ Phiếu 投票信息请见正文。 Tim Scott Multnomah County Director of Elections Macluumaadka Codeynta Gudaha PLEASE NOTE: Multnomah County Elections prints information as submitted. -

A Complete Etymology-Based Hundred Wordlist of Semitic Updated: Items 35–54

Alexander Militarev Russian State University for the Humanities / Santa Fe Institute A complete etymology-based hundred wordlist of Semitic updated: Items 35–54 The paper represents the second part of the author's etymological analysis of the Swadesh wordlist for Semitic languages (the first part having already appeared in Vol. 3 of the same Journal). Twenty more items are discussed and assigned Proto-Semitic reconstructions, with strong additional emphasis on suggested Afrasian cognates. Keywords: Semitic, Afrasian (Afro-Asiatic), etymology glottochronology, lexicostatistics. The object of the present study is analysis of the second portion1 of Swadesh’s 100wordlist for Semitic. It is a follow-up to the author’s second attempt at compiling a complete Swadesh wordlist for most Semitic languages that would fully represent all the branches, groups and subgroups of this linguistic family and provide etymological background for every possible item. It is another step towards figuring out the taxonomy and building a detailed and com- prehensive genetic tree of said family, and, eventually, of the Afrasian (Afro-Asiatic) macro- family with all its branches on a lexicostatistical/glottochronological basis. Several similar attempts, including those by the author (Mil. 2000, Mil. 2004, Mil. 2007, Mil. 2008, Mil. 2010), have been undertaken since M. Swadesh introduced his method of glot- tochronology (Sw. 1952 and Sw. 1955). In this paper, as well as in my previous studies in ge- netic classification, I have relied on Sergei Starostin’s glottochronological method (v. Star.) which is a radically improved and further elaborated version of Swadesh’s method. That the present portion includes only twenty items out of the 100wordlist, instead of a second third (33 items), as I had previously planned, is justified by my efforts to adduce as many Afrasian parallels to Semitic words as possible — more than I did within the first por- tion. -

Fantastic Four Compendium

MA4 6889 Advanced Game Official Accessory The FANTASTIC FOUR™ Compendium by David E. Martin All Marvel characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof The names of characters used herein are fictitious and do are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. not refer to any person living or dead. Any descriptions MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS including similarities to persons living or dead are merely co- are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. incidental. PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the ©Copyright 1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Game Design Rights Reserved. Printed in USA. PDF version 1.0, 2000. ©1987 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 A Brief History of the FANTASTIC FOUR . 2 The Fantastic Four . 3 Friends of the FF. 11 Races and Organizations . 25 Fiends and Foes . 38 Travel Guide . 76 Vehicles . 93 “From The Beginning Comes the End!” — A Fantastic Four Adventure . 96 Index. 102 This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc., and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. All characters appearing in this gamebook and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. -

Thorragnarok59d97e5bd2b22.Pdf

©2017 Marvel. All Rights Reserved. CAST Thor . .CHRIS HEMSWORTH Loki . TOM HIDDLESTON Hela . CATE BLANCHETT Heimdall . .IDRIS ELBA Grandmaster . JEFF GOLDBLUM MARVEL STUDIOS Valkyrie . TESSA THOMPSON presents Skurge . .KARL URBAN Bruce Banner/Hulk . MARK RUFFALO Odin . .ANTHONY HOPKINS Doctor Strange . BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH Korg . TAIKA WAITITI Topaz . RACHEL HOUSE Surtur . CLANCY BROWN Hogun . TADANOBU ASANO Volstagg . RAY STEVENSON Fandral . ZACHARY LEVI Asgardian Date #1 . GEORGIA BLIZZARD Asgardian Date #2 . AMALI GOLDEN Actor Sif . CHARLOTTE NICDAO Odin’s Assistant . ASHLEY RICARDO College Girl #1 . .SHALOM BRUNE-FRANKLIN Directed by . TAIKA WAITITI College Girl #2 . TAYLOR HEMSWORTH Written by . ERIC PEARSON Lead Scrapper . COHEN HOLLOWAY and CRAIG KYLE Golden Lady #1 . ALIA SEROR O’NEIL & CHRISTOPHER L. YOST Golden Lady #2 . .SOPHIA LARYEA Produced by . KEVIN FEIGE, p.g.a. Cousin Carlo . STEVEN OLIVER Executive Producer . LOUIS D’ESPOSITO Beerbot 5000 . HAMISH PARKINSON Executive Producer . VICTORIA ALONSO Warden . JASPER BAGG Executive Producer . BRAD WINDERBAUM Asgardian Daughter . SKY CASTANHO Executive Producers . THOMAS M. HAMMEL Asgardian Mother . SHARI SEBBENS STAN LEE Asgardian Uncle . RICHARD GREEN Co-Producer . DAVID J. GRANT Asgardian Son . SOL CASTANHO Director of Photography . .JAVIER AGUIRRESAROBE, ASC Valkyrie Sister #1 . JET TRANTER Production Designers . .DAN HENNAH Valkyrie Sister #2 . SAMANTHA HOPPER RA VINCENT Asgardian Woman . .ELOISE WINESTOCK Edited by . .JOEL NEGRON, ACE Asgardian Man . ROB MAYES ZENE BAKER, ACE Costume Designer . MAYES C. RUBEO Second Unit Director & Stunt Coordinator . BEN COOKE Visual Eff ects Supervisor . JAKE MORRISON Stunt Coordinator . .KYLE GARDINER Music by . MARK MOTHERSBAUGH Fight Coordinator . JON VALERA Music Supervisor . DAVE JORDAN Head Stunt Rigger . ANDY OWEN Casting by . SARAH HALLEY FINN, CSA Stunt Department Manager . -

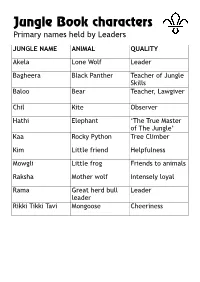

Jungle Book Characters Primary Names Held by Leaders

Jungle Book characters Primary names held by Leaders JUNGLE NAME ANIMAL QUALITY Akela Lone Wolf Leader Bagheera Black Panther Teacher of Jungle Skills Baloo Bear Teacher, Lawgiver Chil Kite Observer Hathi Elephant ‘The True Master of The Jungle’ Kaa Rocky Python Tree Climber Kim Little friend Helpfulness Mowgli Little frog Friends to animals Raksha Mother wolf Intensely loyal Rama Great herd bull Leader leader Rikki Tikki Tavi Mongoose Cheeriness Jungle Book characters Secondary names held by Leaders JUNGLE NAME ANIMAL QUALITY Grey Brother Brother Wolf Loyal friend Ikki Porcupine Truthful Jacala Crocodile Acting Mang Bat Obedience Mao / Mor Peacock Smart appearance Mysa Wild Buffalo Good hearing Phao Wolf Leader (to be) Wontolla Solitary Wolf Lies out from any Pack / hopping Other names held by Leaders JUNGLE NAME ANIMAL QUALITY Father Wolf Wolf Father Kala Nag The Wise Old (Name meaning: Elephant Black Snake) Tha First of Elephants Creator & Judge Jungle Book characters Jungle villains JUNGLE NAME ANIMAL QUALITY Bander-log Monkey People People without a Law Buldeo Village Hunter Hunter & teller of stories (about himself) Dewanee Water Madness Feared by all Jungle Creatures Dholes Red Dogs Killers Gidur-log Jackel People - Gonds Hunters Little wild people of the jungle Grampus Killerwhale Killer Karait Dusty Brown Death Snakeling Ko Crow Chatter Mugger Ghaut Large Crocodile - Nag Cobra Kills for pleasure Nagaina Nag’s Wicked Wife Kills for pleasure Sea Vitch Walrus No manners Samthur Cattle - Shere Khan Tiger Bullying & Killer Tabaqui -

Winter 2008 10Th International Conference on OI Held in Belgium

133920_OIF_Winter:Layout 1 12/4/2008 12:46 PM Page 1 BreakthroughTHE NEWSLETTER OF THE OSTEOGENESIS IMPERFECTA FOUNDATION Vol. 33 No. 4 Winter 2008 10th International Conference on OI Held in Belgium OI Foundation CEO, Tracy Hart, attended and represented included OI Foundation medical advisors Dr. Peter Byers, the OI Foundation at the 10th International Conference on Dr. Francis Glorieux, Dr. Brendan Lee, Dr. Joan Marini, Dr. Osteogenesis Imperfecta in Ghent, Belgium in October. Jay Shapiro, Dr. Reid Sutton and Dr. Matthew Warman. The meeting brought together scientists, researchers and Also in attendance was parent and neonatologist Dr. Bonnie physicians from all over the world to discuss the current Landrum. progress in diagnosis and treatment of OI. Besides reviewing important clinical and radiographic aspects of OI, The meeting clearly showed how important communication an update on the genetic and molecular aspects of OI was is across the globe in finding new treatments for OI and presented and current view points on management and how important it will be in the future to continue to bring the treatment of OI were discussed. experts from around the world together to report on their valuable and cutting edge research. Every 3 years, physicians and scientists from all over the world who are leaders in clinical care, genetics and bone In addition to the scientific portion of the meeting, the OIFE biology related to OI gather to share their latest findings. (Osteogenesis Imperfecta Foundation Europe) held their This year’s meeting, attended by 150 people including 20 family meeting in a town close to Ghent enabling those American physicians and scientists, created a forum where attending the scientific meeting to attend portions of the a wide range of medical specialties including orthopedics, family meeting and the welcome reception. -

Statira “Star” Simmons Wall ’08 a Laker for Life

The Laker FALL 2020 Statira “Star” Simmons Wall ’08 A Laker for Life 1 | LAKER Table of Contents EDITORS Shellie Javier Kala Montoya 3 16 FROM THE TOP 3: THINGS I LEARNED GRAPHIC DESIGNER HEAD OF SCHOOL DURING “SAFER AT HOME” John Ritter PHOTOGRAPHY Shellie Javier Kala Montoya Ross Monagle 4 17 PRINTER HAWK HILL GRADUATION Thomas Press (Waukesha, Wis.) HAPPENINGS RECAP BOARD OF TRUSTEES Adam Rix, President John Griner, Vice President Martin Ditkof, Secretary Greg Ploch ’80, Treasurer 6 18 McKenna Bryant ’95 Scott Gass FACULTY FEATURE: SENIOR Alex Inman REBECCA TIFFANY SPOTLIGHT Amy LaMacchia Holly Myhre ’95 John O’Horo Joan Shafer Margaret Tackes Paul Verdu 9 20 HAWK HILL ALUMNI The Laker is published by University Lake HISTORY NEWS School. It is mailed free of charge, twice a year, to alumni and friends of the school. To update your address or share comments and ideas: Email: [email protected] Call: 262-367-6011 12 22 FEATURE: STAR SIMMONS WALL ’08 LAKERS Write: Advancement Office, A LAKER FOR LIFE WE’VE LOST University Lake School, P.O. Box 290, Hartland, WI 53029 2 | LAKER Photo by Ross Monagle I hope this edition of The FromLaker finds you and theyours safe Headand healthy during thisof pandemic. School We have faced so many challenges this year, but we will not be deterred from moving forward. As a school, we continue to look ahead through the lens of our strategic planning so that our best days are ahead of us. With winter coming soon, I am reminded of a beautiful Wisconsin winter day in January of 2020. -

Men's Soccer Recruits Hope to Make the 'Cut'

CollegianThe September 09, 2011 The Grove City College Student Newspaper Summer classes have College observes 10th anniversary of 9/11 beginnings in 1800s The Grove City College Republicans will host the fifth annual 9/11 Flag Me- morial to commemorate the lives that Kristie Eshelman week long Bible school. were lost during the terrorist attacks Collegian Writer The College issued Bulletins of September 11. Along with a brief to describe the classes, housing memorial service for students at Vespers This summer, Grove City and registration procedures for on Sunday night, 2,997 flags will be College students had the the summer term and the Bible erected on the College’s Lower Quad. opportunity to take online school. The 1939 Bulletin de- “This is a memorial service to re- classes such as Creative Writ- scribed a thriving summer term, member the price of freedom paid not ing, Business Statistics, Cultur- though the Bible school had only by the victims of 9-11, but also ally Relevant Pedagogy and by that time decreased to one their families and the soldiers who have several other courses. Unlike week. The College’s tuition for subsequently given their lives to bring intersession course, the online the 1939 summer term was at the perpetrators to justice,” said senior classes allowed students to an all-time low: $35 for tuition Andrew Patterson, chairman of the meet course requirements at and $51 for housing. Grove City College Republicans. home in a more relaxed pe- Women stayed in Colonial At 7:20 p.m., students will gather riod of six weeks. -

Good Grief: an Analysis of the Character Development of Tonya in August Wilson’S King Hedley II Through the Lens of “The Five Stages of Grief”

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2020 Good grief: an analysis of the character development of Tonya in August Wilson’s King Hedley II through the lens of “the five stages of grief”. Kala Ross University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Acting Commons Recommended Citation Ross, Kala, "Good grief: an analysis of the character development of Tonya in August Wilson’s King Hedley II through the lens of “the five stages of grief”." (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3371. Retrieved from https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd/3371 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOOD GRIEF: AN ANALYSIS OF THE CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT OF TONYA IN AUGUST WILSON’S KING HEDLEY II THROUGH THE LENS OF “THE FIVE STAGES OF GRIEF” By Kala Ross B.S., Tennessee State University, 2017 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Theatre Arts Department of Theatre University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2020 Copyright 2020 by Kala Ross All rights reserved GOOD GRIEF: AN ANALYSIS OF THE CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT OF TONYA IN AUGUST WILSON’S KING HEDLEY II THROUGH THE LENS OF “THE FIVE STAGES OF GRIEF” By Kala Ross B.S., Tennessee State University, 2017 A Thesis Approved on April 3, 2020 by the following Thesis Committee __________________________________ Johnny Jones __________________________________ Dr. -

Follow Us on Facebook and Twitter @Back2past for Updates

6/26 Silver Age Extravaganza: Marvel, DC, Dell, & More! 6/26/2021 This session will broadcast LIVE via ProxiBid.com at 6 PM on 6/26/21! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast! See site for full terms. LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 1 Auction Policies 1 16 Dennis The Menace Silver Age Comic Lot 1 Lot of (4) Hallden/Fawcett comics. #43, 47, 74, and 87. VG-/VG 2 Amazing Spider-Man #3/1st Dr. Octopus! 1 First appearance and origin of Dr. Octopus. VG- condition. condition. 3 Tales to Astonish #100 1 17 Challengers of the Unknown #13/22/27 1 Classic battle the Hulk vs the Sub-Mariner. VF/VF+ with offset DC Silver Age. VG to FN- range. binding and bad staple placement. 18 Challengers of the Unknown #34/35/48 1 DC Silver Age. VG-/VG condition. 4 Tales to Astonish #98 1 Incredible Adkins and Rosen undersea cover. VF- condition. 19 Challengers of the Unknown #49/50/53/61 1 DC Silver Age. VG+/FN condition. 5 Tales to Astonish #97 1 Hulk smash collaborative cover by Marie Severin, Dan Adkins, and 20 Flash Gordon King/Charlton Comics Lot 1 Artie Simek. FN+/ VF- with bad staple placement. 6 comics. #3-5, and #8 from King Comics and #12 and 13 from Charlton. VG+ to FN+ range. 6 Tales to Astonish #95/Semi-Key 1 First appearance of Walter Newell (becomes Stingray). -

Fantastic Four Compendium

MA4 6889 Advanced Game Official Accessory The FANTASTIC FOUR™ Compendium by David E. Martin All Marvel characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof The names of characters used herein are fictitious and do are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. not refer to any person living or dead. Any descriptions MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS including similarities to persons living or dead are merely co- are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. incidental. PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the ©Copyright 1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Game Design Rights Reserved. Printed in USA. PDF version 1.0, 2000. ©1987 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 A Brief History of the FANTASTIC FOUR . 2 The Fantastic Four . 3 Friends of the FF. 11 Races and Organizations . 25 Fiends and Foes . 38 Travel Guide . 76 Vehicles . 93 “From The Beginning Comes the End!” — A Fantastic Four Adventure . 96 Index. 102 This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc., and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. All characters appearing in this gamebook and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. -

EL UNIVERSO CROMÁTICO DE Mccoy, Medusa Melter Mentallo Mephisto Merlin Norton

El color de su creatividad Colores predominantes Stan Lee presentó al mundo personajes notables por su complejidad y realismo. Creó íconos del cómic como: Spider-Man, X-Men, Iron Man, Thor o Avengers, casi siempre acompañado de los dibujantes Steve Ditko y Jack Kirby. En el siguiente desglose te presentamos los dos colores Desgl se Nombre del predonimantes en el diseño de cada una de sus creaciones. personaje Abomination Absorbing Aged Agent X Aggamon Agon Aireo Allan, Liz Alpha Amphibion Ancient One Anelle Ant-Man Ares Avengers* Awesome Man Genghis Primitive Android Balder Batroc the Beast Beetle Behemoth Black Bolt Black Knight Black Black Widow Blacklash Blastaar Blizzard Blob Bluebird Boomerang Bor Leaper Panther Betty Brant Brother Blockbuster Blonde Brotherhood Burglar Captain Captain Carter, Chameleon Circus Clea Clown Cobra Cohen, Izzy Collector Voodoo Phantom of Mutants** Barracuda Marvel Sharon of Crime** Crime Crimson Crystal Cyclops Daredevil Death- Dernier, Destroyer Diablo Dionysus Doctor Doctor Dormammu Dragon Man Dredmund Dum Dum Master Dynamo Stalker Jacques Doom Faustus the Druid Dugan Eel Egghead Ego the Electro Elektro Enchantress Enclave** Enforcers** Eternity Executioner Fafnir Falcon Fancy Dan Fandral Fantastic Farley Living Planet Four** Stillwell Fenris Wolf Fin Fang Fisk, Richard Fisk, Fixer Foster, Bill Frederick Freak Frigga Frightful Fury, Nick Galactus Galaxy Gargan, Mac Gargoyle Gibbon Foom Vanessa Foswell Four** Master Gladiator Googam Goom Gorgilla Gorgon Governator Great Green Goblin Gregory Grey Grey, Elaine Grey, Dr. Grey, Jean Grizzly Groot Growing Gambonnos** Gideon Gargoyle John Man The Guardian H.E.R.B.I.E. Harkness, Hate Monger Hawkeye Heimdall Hela Hera Herald of Hercules High Happy Hogun Hulk Human Human Project** Agatha Galactus Evolutionary Hogan Cannonball Torch Iceman Idunn Immortus Imperial Impossible Inhumans** Invisible Iron Man Jackal John J.