Writ of Summons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

NIGERIA COMPUTER SOCIETY Run Date: July 12, 2016 MEMBER's CURRENT STATUS - FINANCIALLY Run Time: 3:31:42PM

Page 1 of 489 NIGERIA COMPUTER SOCIETY Run Date: July 12, 2016 MEMBER'S CURRENT STATUS - FINANCIALLY Run Time: 3:31:42PM GRADE LEVEL FELLOW S/N REG-NO SURNAME OTHER-NAMES CURRENT STATUS 1 00019 Abass Olaide SPECIAL-WAIVER 2 00302 Abodunde T T DORMANT 3 01000 Abubakar Iya DORMANT 4 00164 ABUGO ADEFEMI ADETUTU INACTIVE 5 00426 Achumba Allwell DE-LISTABLE 6 00834 Adagunodo Rotimi E ACTIVE 7 03946 Adedowole Mike INACTIVE 8 01582 Adegoke Rasheed Aderemi LIFE-MEMBER 9 00085 Adeniran Raheem DORMANT 10 00758 Adeoye Elijah Aderogba ACTIVE 11 01187 Aderounmu Adesola Ganiyu ACTIVE 12 01822 Adetonwa Adisa Dauda INACTIVE 13 00213 Adewumi David Olambo ACTIVE 14 00284 Adewumi Sunday Eric LIFE-MEMBER 15 00036 Afolabi Monisoye Olorunnisola LIFE-MEMBER 16 02366 Aghanenu Ernest Odiche LIFE-MEMBER 17 00197 Agogbuo Chinedu Christopher LIFE-MEMBER 18 00021 Agu Simeon DE-LISTABLE 19 00067 Aiyerin Charles Olusegun DORMANT Page 2 of 489 NIGERIA COMPUTER SOCIETY Run Date: July 12, 2016 MEMBER'S CURRENT STATUS - FINANCIALLY Run Time: 3:31:47PM GRADE LEVEL FELLOW S/N REG-NO SURNAME OTHER-NAMES CURRENT STATUS 20 04434 Ajayi Lanre LIFE-MEMBER 21 01605 Ajisomo Oyedele ACTIVE 22 00298 Akanbi Timothy DE-LISTABLE 23 00040 Akinde Adebayo Dada INACTIVE 24 00072 AKINLADE TITILOLA OLUSOLA LIFE-MEMBER 25 00236 Akinniyi Funso DORMANT 26 03358 Akinnusi Sehinde Lawrence ACTIVE 27 00096 Akinsanya Adebola Olatunji LIFE-MEMBER 28 02308 Akinyokun Oluwole Charles LIFE-MEMBER 29 00254 Akuwudike George DE-LISTABLE 30 00571 Aladekomo Ben Ademola. LIFE-MEMBER 31 01006 Aladesulu Stephen -

Pattern and Determinants of Nutritional Status Among Children Attending Primary Schools in a Rural and an Urban Community in Osun State; a Comparative Study

Pattern and Determinants of Nutritional Status among Children attending Primary Schools in a Rural and an Urban Community in Osun State; a Comparative study BY ADEOMI, Adeleye Abiodun DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY MEDICINE, LAUTECH TEACHING HOSPITAL, OSOGBO To The National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria Faculty of Public Health In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the Fellowship of the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria (Public Health) November, 2013 DECLARATION I, ADEOMI Adeleye Abiodun, hereby declare that this work was carried out by me under the supervision of Dr. J. O. Bamidele. This work has not been submitted for any other examination or publication. _______________________________ Dr. ADEOMI Adeleye Abiodun Candidate ii CERTIFICATION We hereby certify that this research titled “Pattern and Determinants of Nutritional Status among School-Age Children in a Rural and an Urban Community in Osun State; a Comparative study” was carried out and completed by ADEOMI Adeleye Abiodun in the Department of Community Medicine, LAUTECH, Osogbo and under the supervision of Dr. J. O. Bamidele. ___________________________________ Dr. Bamidele J. O. Supervisor Consultant and Reader, Community Medicine Department, LAUTECH Teaching Hospital. ___________________________________ Dr. Olugbenga-Bello A.I. Head of Department Community Medicine Department, LAUTECH Teaching Hospital. Ogbomoso. iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to God Almighty, who alone is worthy of all the praise and glory. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to heartily acknowledge the understanding, support, encouragement and assistance of my supervisor Dr J.O. Bamidele during the course of carrying out this research. Thank you for always believing in me, and accepting to guide me through this work. -

Public Disclosure Authorized

INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION THE INSPECTION PANEL 1818 H Street, N.W. Telephone: (202) 458-5200 Washington, D.C. 20433 Fax: (202) 522-0916 Email: [email protected] Eimi Watanabe Chairperson Public Disclosure Authorized JPN REQUEST RQ13/09 July 16, 2014 MEMORANDUM TO THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS OF THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Request for Inspection Public Disclosure Authorized NIGERIA: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P071340) Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions Please find attached a copy of the Memorandum from the Chairperson of the Inspection Panel entitled "Request for Inspection - Nigeria: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P071340) - Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions", dated July 16, 2014 and its attachments. This Memorandum was also distributed to the President of the International Development Association. Public Disclosure Authorized Attachment cc.: The President Public Disclosure Authorized International Development Association INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION THE INSPECTION PANEL 1818 H Street, N.W. Telephone: (202) 458-5200 Washington, D.C. 20433 Fax : (202) 522-0916 Email: [email protected] Eimi Watanabe Chairperson IPN REQUEST RQ13/09 July 16, 2014 MEMORANDUM TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Request for Inspection NIGERIA: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P071340) Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions Please find attached a copy of the Memorandum from the Chairperson of the Inspection Panel entitled "Request for Inspection - Nigeria: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P07 J340) - Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions" dated July 16, 2014 and its attachments. -

Finance-And-Revenue-Mobilization

FINANCE & REVENUE MOBILIZATION SECTOR 2020 – 2022 MEDIUM-TERM SECTOR STRATEGY (MTSS) JULY, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENT Pages Foreword ii-iii Acknowledgements iv List of Tables v Executive Summary 1-2 1 CHAPTER ONE – OBJECTIVES OF THE DOCUMENT 1.1 Objectives of the MTSS Document 3 1.2 Outline of the Structure of the Document 3-4 1.3 Process used for the MTSS Development 4 1.4 Summary of the sector’s Programmes, Outcomes and Related Expenditures 5 2 CHAPTER TWO – THE SECTOR AND POLICY IN THE STATE 2.1 A Brief Introduction to the State 6-8 2.2 Overview of the Finance and Revenue Mobilization Sector 8 2.3 The Current Situation in the Sector 9 2.4 Sector Policy 10 2.5 The Sector’s, Mission, Vision and Core Values 10-11 2.6 The Sector’s Objectives and Programmes for the MTSS Period 11-14 3 CHAPTER THREE – THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECTOR STRATEGY 3.1 Major Strategic Challenges 15 3.2 Resource Constraints 16 3.3 Projects Prioritization 17-18 3.4 Personnel and Overhead Costs: Existing and Projections 19 3.5 Contributions from our Partners 19 3.6 Cross-Cutting Issues 19 3.7 Outline of Key Strategies 20-21 3.8 Justification 22 3.9 Responsibilities and Operational Plan 22-23 4 CHAPTER FOUR – THREE-YEAR EXPENDITURE PROJECTIONS 4.1 The process used to make Expenditure Projections 24 4.2 Outline Expenditure Projections 24 5 CHAPTER FIVE – MONITORING AND EVALUATION 5.1 Conducting Annual Sector Review 25 5.2 Organizational Arrangements 25-26 i FOREWORD The imperative of effective revenue mobilisation, generation and allocation cannot be over-emphasised. -

Sovereign-Trust-Insurance-2011-Annual-Report.Pdf

1 A N N U A L R E P O R T & A C C O U N T S 2 0 1 1 V I S I O N To be a leading brand providing insurance and financial services of global standards. M I S S I O N To enhance the every day life of our customers t h ro u g h i n n o v a t i v e insurance and financial services while creating exceptional value for our shareholders. CORE VALUES Superior Customer Service Innovation Professionalism Integrity Empathy Team Spirit. A N N U A L R E A C C O P O R T U N T S & 2 2 0 1 1 Notice of AGM 03 Corporate Information 05 Management Team 07 Financial Highlights 08 Chairman’s Statement 09 Board of Directors 14 Management Team 18 Directors’ Report 24 Statement of Directors' Responsibilities 31 Independent Auditor’s Report 32 C O N T E N T S Report of the Audit Committee 33 Statement of Significant Accounting Policies 34 Balance Sheet 40 Profit and Loss Account 41 Revenue Account 42 Statement of Cash Flow 43 Notes to the Financial Statements 45 Statement of Value Added 63 Five-Year Financial Summary 64 Share Capital History 65 Mandate Form 66 Proxy Form 67 Admission Form 68 Unclaimed Dividend Warrant List 69 3 A N N U A L R E P O R T & A C C O U N T S 2 0 1 1 1 7 T H A G M N O T I C E 4 A N N U A L R E P O R T & A C C O U N T S 2 0 1 1 N O T I C E O F T H E 1 7 T H A N N U A L G E N E R A L M E E T I N G TO ALL THE SHAREHOLDERS NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL NOTES CLOSURE OF REGISTER MEETING PROXIES The Register of members and Only a member of the Company Transfer Books of the Company shall NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN to you entitled to attend and vote at the be closed from 24th day of May that the 17th Annual General General Meeting is entitled to 2012 to 31st day of May 2012 (both Meeting of Sovereign Trust appoint a proxy in his/her stead. -

Final List of Delegations

Supplément au Compte rendu provisoire (21 juin 2019) LISTE FINALE DES DÉLÉGATIONS Conférence internationale du Travail 108e session, Genève Supplement to the Provisional Record (21 June 2019) FINAL LIST OF DELEGATIONS International Labour Conference 108th Session, Geneva Suplemento de Actas Provisionales (21 de junio de 2019) LISTA FINAL DE DELEGACIONES Conferencia Internacional del Trabajo 108.ª reunión, Ginebra 2019 La liste des délégations est présentée sous une forme trilingue. Elle contient d’abord les délégations des Etats membres de l’Organisation représentées à la Conférence dans l’ordre alphabétique selon le nom en français des Etats. Figurent ensuite les représentants des observateurs, des organisations intergouvernementales et des organisations internationales non gouvernementales invitées à la Conférence. Les noms des pays ou des organisations sont donnés en français, en anglais et en espagnol. Toute autre information (titres et fonctions des participants) est indiquée dans une seule de ces langues: celle choisie par le pays ou l’organisation pour ses communications officielles avec l’OIT. Les noms, titres et qualités figurant dans la liste finale des délégations correspondent aux indications fournies dans les pouvoirs officiels reçus au jeudi 20 juin 2019 à 17H00. The list of delegations is presented in trilingual form. It contains the delegations of ILO member States represented at the Conference in the French alphabetical order, followed by the representatives of the observers, intergovernmental organizations and international non- governmental organizations invited to the Conference. The names of the countries and organizations are given in French, English and Spanish. Any other information (titles and functions of participants) is given in only one of these languages: the one chosen by the country or organization for their official communications with the ILO. -

Lt. Col. Dauda Musa Komo

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 21, Number 32, August 12, 1994 Interview: Lt. Col. Dauda Musa Komo There is a real potential for development in Nigeria Colonel Komo is the administrator/governor of Rivers State, conflicts. The Oganis some time ago attacked an Andoki Nigeria's largest oil-producing state. Lawrence Freeman village. The Andokis are in the lbo-speaking part of the state; and Uwe Friesecke interviewed him on July 4. the lbo-speaking people are generally Christians, and they were in church services last Easter Sunday, when the Ogani EIR: What percentage of oil produced in Nigeria comes people attacked them. from your region? Second, you have Oganis versus the petrol companies in Komo: There are about eight states that constitute the major the state. Shell had virtually closed all its operations on the petroleum-producing states in Nigeria. Of the eight, Rivers internal Ogani land. Right now, there isn't any oil explora State is the largest producer of oil. Its contribution ranges tion or activity taking place on Ogani land. from 30 to 45% of total oil produced in Nigeria, which is The biggest conflict with respect to the Oganis, however, quite substantial. is conflict within this ethnic group. This was most clearly seen in what happened this spring I when Ken Saro-Wiwa's EIR: Have you seen, over the past several months, an im NYCOP [National Youth Council �f Ogani People] attacked provement in the development, exploration, and export of four prominent Ogani sons and killed them, put the bodies in oil, since you have reformed some of the structural adjust a car, pushed it off into the bush, and set it afire. -

MAY 3, 2021 Convert.Cdr

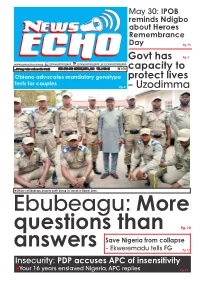

May 30: IPOB reminds Ndigbo about Heroes Remembrance Day Pg. 13 Govt has Pg. 3 @newsechonigeria @newsechonigeria @newsechonigeria ...Strong voice echoes the truth ISSN: 2736-0512 MONDAY, MAY 3 , 2021 VOL. 2 NO. 52 N150 capacity to Obiano advocates mandatory genotype protect lives tests for couples Pg. 2 – Uzodimma Officers of Ebubeagu Security outfit during its launch in Ebonyi State. Ebubeagu: More questions than Pg. 10 answers Save Nigeria from collapse – Ekweremadu tells FG Pg. 12 Insecurity: PDP accuses APC of insensitivity Your 16 years enslaved Nigeria, APC replies Pg.Pg. 18 17 News Echo Monday, May 3, 2021 Page 2 NEWS Obiano advocates mandatory genotype test for couples From Karen James, and support for people of the Borough for part- urging other men to sup- tion to Mrs. Obiano said He thanked her for be- Nnewi living with sickle cell dis- nering the NGO since port their wives to ful- her excellent work and ing steadfast in her cause orders and other disabili- 2019, stressing that the fill their dreams as such contributions in creating of charity by using her he Founder of ties. relationship had achieved encouragement could awareness and support for NGO to bring medical Caring Family En- In her remarks, Mrs. huge results. propel them to greater people living with sick- and emotional solace to Thancement Initia- Obiano who recalled the She noted that her hus- heights. le cell anemia and other those living with the sick- tive (CAFE), Mrs. Ebe- pain of losing one of her band, Gov. Willie Obiano Earlier, the Mayor, His disabilities, through her le cell as well as children lechukwu Obiano has daughters to sickle cell deserved praise for sup- Worship, Ernest Ezea- charity organisation, the suffering from congenital appealed that mandatory disease years ago, main- porting her dedication to jughi who, presented CAFE was commenda- mouth disorders (cleft lip genotype tests for all cou- tained that the experience the humanitarian drive, the award of recogni- ble. -

Voting Behaviour in Osun 2014 Governorship Election in Nigeria

Public Policy and Administration Research www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-5731(Paper) ISSN 2225-0972(Online) Vol.4, No.8, 2014 Voting Behaviour in Osun 2014 Governorship Election in Nigeria Adeolu Durotoye, PhD Department of Political Science and International Studies, College of Social and Management Sciences Afe Babalola University, Ado Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria Email: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract The August 9, 2014 governorship election in Osun state, South West Nigeria was another test run for the Independent Electoral Commission (INEC) towards the 2015 General election. The election was important because it occurred not long after the Ekiti state governorship election of June 21, 2014 which was largely adjudged to be free and fair. Besides, the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) candidate won the Ekiti election by defeating the All Progressive Congress (APC) candidate who was the incumbent. The Ekiti election increased the momentum in Osun as the PDP was emboldened that it could pull the same feat in Osun, while the APC was hell bent on avoiding another slip.At the end of the day, the APC won in Osun and the PDP lost. What was responsible for this outcome? Why was the PDP not able to repeat the feat it achieved in Ekiti? These are the questions facing this paper. This paper will blend the unique aspects of the Osun election with a more general understanding of electoral behaviour to create a full explanation. Keywords : Voting behaviour, Election, Nigeria, Osun state, INEC, PDP, APC, Aregbesola, Omisore 1. Introduction The August 9, 2014 governorship election in Osun state, South West Nigeria was another test run for the Independent Electoral Commission (INEC) towards the 2015 General election. -

Annex I Request for Inspection

ANNEX I REQUEST FOR INSPECTION In the Matter of the Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (Project ID: P071340) TO: Executive Secretary By email: [email protected] The Inspection Panel [email protected] 1818 H Street NW, Mail Stop: MC10-1007 Washington, D.C. 20433 U.S.A. FILED BY: Social and Economic Rights Action Center (SERAC) Counsel of record for members of the Badia community, Lagos Plot 758 Chief Thomas Adeboye Road Isheri, Lagos NIGERIA We, the Social and Economic Right Action Center (SERAC), a Lagos-based non- governmental, nonpartisan and voluntary initiative concerned with the promotion and protection of social and economic rights in Nigeria, have been mandated by individuals, families and groups living in the Badia area of Lagos State to file the present Request for Inspection (Exhibit A – letter of consent from project-affected persons from Badia East). In support of this Request, we state the following: 1. The World Bank has financed the implementation of the Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (hereinafter referred to as LMDGP) with Project ID: P071340 in Lagos State, Nigeria. The LMDGP aims to increase sustainable access to basic urban services through investments in critical infrastructure. Amongst other objectives, through “urban upgrading” activities worth US$ 39.77 million, the LMDGP seeks to build the capacity of the Lagos State Urban Renewal Authority (LASURA) to assess, develop, plan and coordinate the execution of a city-wide upgrading program, through the execution of upgrading subprojects in nine of the city’s largest slums (as identified in 1995: Agege, Ajegunle, Amukoko, Badia, Iwaya, Makoko, Ilaje, Bariga, Ijeshatedo/Itire. -

Mise En Page 1

The Africa Experts Ecobank Nigeria Plc Annual Report RC No: 89773 2010 15:27 The Ecobank Network 2 Ecobank Nigeria Annual Report 2010 Ecobank Nigeria branches Head Office Branch Plot 21, Ahmadu Bello Way - P.O. Box 72688, Victoria Island - Lagos - NIGERIA Tel: (234) 1 2710391/5 - Fax: (228) 221 51 19 CROSS RIVER / AKWA IBOM Abak Netpost Ogboefere Market NO 1 Ikot Ekpene Road Abak Tel.: (234) 806 099 7484/704 145 0365; CROSS RIVER STATE Tel.: (234) 07041450461 (234) 803 387 1772/704 145 0254 Old Market Road Calabar II EAST 24 Old Market Road, Onitsha 15, Murtala Mohammed Highway, Tel.: (234) 704 145 0386/704 145 0171 Calabar ABIA STATE Williams Tel.: (234) 803 720 4656/805 839 9981 7 William Street, Onitsha Mary Slessor Factory Road, Aba. Tel.: (234) 704 145 0366/803 335 7444; 12 Mary Slessor Avenue, Calabar No. 1, Factory Road, Aba. (234) 704 145 0907 Tel.: (234) 87 290 474/704 145 0474 Tel.: (234) 07041450398/07041450400 Obudu Ekeoha ENUGU STATE No. 2 Government Station Ranch Road, Ekeoha Shopping Complex, Obudu Ehi/Asa Road, Aba Okpara Avenue I Tel.: (234) 708 987 7826/803 418 6012 Tel.: (234) 704 145 0389; 704 145 0415 31A Okpara Avenue, Enugu Ogoja Govt. Station Layout, Umuahia Tel.: 234) 704 145 0381/704 145 0170; 19 MLA Hospital Road Igoli Ogoja Plot 110 Govt. Station Layout, Umuahia (234) 42 290 578/704 145 0380 Tel.: (234) 08037134913/08028363500 Tel.: (234) 704 145 0411/704 145 0225 Okpara Avenue II Ikom Faulks Road Aba 20B Okpara Avenue, Enugu 72 Calabar Road, Four Corner, Ikom 187 FAULKS ROAD,ABA ABIA-STATE Tel.: (234) 704 145