INFORMATION to USERS While the Most Advanced Technology Has

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volunteer Tourism in Napo Province

NATIONAL TOURISM GUIDE TOURISM OF VOLUNTEERISM IN NAPO PROVINCE BY NATALY GABRIELA ALBAN PINO QUITO – ECUADOR NOVEMBER 2014 VOLUNTEER TOURISM IN NAPO PROVINCE BY: NATALY GABRIELA ALBAN PINO CHECKED BY: Firma:____________________ Firma:____________________ Professional Guide Tutor Firma:____________________ Firma:___________________ English Teacher Carrere Coordinator GRATITUDE First of all I would like to thank God for allowing me to overcome my fears to complete this professional achievement, I thank my parents Patricia and Fernando who have been my example and my support in my development as a person, I thank the UCT University and my teachers for all the knowledge imparted. And I thank my boyfriend Cristopher Valencia who motivates me every day to be better and to overcome any obstacles that comes in my life. DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the most important people in my life, my parents, my sisters, my nephew and the loves of my life My son Julian and my boyfriend Cristopher, I share this achievement with them. INDEX i. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 ii. INTRODUCTION 3 iii. TOPIC DEFINITION AND JUSTIFICATION 4 iv. OBJECTIVES 4 v. METHODS 5 vi. ROUTES 6 vii. WEIGHTING ROUTE 7 viii. OPERATING ITINERARY 8 ix. OPERATING ITINERARY BUDGET 10 x. ATTRACTIONSRESEARCH 12 xi. WEIGHTING ATRACTION SAN CARLOS COMMUNITY 16 xii. WEIGHTING ATRACTION OPERATIVE TOUR 17 xiii. BIBLIOGRAPHY 27 TOURISM OF VOLUNTEERISMIN THE NAPO PROVINCE, ECUATORIAN RAIN FOREST xiv. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Nowadays, the tourism of volunteerism is a reality. Many people around the world have changed their opinion about trips. Many years ago, tourists preferred traveling with other purposes but now things are changing. -

Indigenous and Social Movement Political Parties in Ecuador and Bolivia, 1978-2000

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Democratizing Formal Politics: Indigenous and Social Movement Political Parties in Ecuador and Bolivia, 1978-2000 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Jennifer Noelle Collins Committee in charge: Professor Paul Drake, Chair Professor Ann Craig Professor Arend Lijphart Professor Carlos Waisman Professor Leon Zamosc 2006 Copyright Jennifer Noelle Collins, 2006 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Jennifer Noelle Collins is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2006 iii DEDICATION For my parents, John and Sheila Collins, who in innumerable ways made possible this journey. For my husband, Juan Giménez, who met and accompanied me along the way. And for my daughter, Fiona Maité Giménez-Collins, the beautiful gift bequeathed to us by the adventure that has been this dissertation. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS SIGNATURE PAGE.……………………..…………………………………...…...…iii DEDICATION .............................................................................................................iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ..............................................................................................v -

Tungurahua Province

UNIVERSIDAD DE ESPECIALIDADES TURISTICAS THE MOST RELAXATION & HEALTH IN TUNGURAHUA PROVINCE Health Tour 2 day – 1 night 3 Switzerland (60 years) Pichincha – Tungurahua Provinces Written By: Adriana Paredes Teacher: Edison Molina To obtain: Bachelor of National Tour Guide Quito, June, 2013 1 Dedications Firstly, I want to thank God for giving me the strength to finish my career with success. I want to dedicate this work to all my family, especially for my mother who is an important person in my life and always stay with me. My husband who helps and gave me unconditional support and important advantages and I love a lot for all. Finally my dear daughter who suffered sometimes the necessity of her mom because I should go to study but She is my fortress in each one of my decisions. 2 Gratitude When I started this project I didn’t have much knowledge about the Tungurahua Province. But thanks to my teacher who taught me and guided me I was able to do this tour. I also want to thank my husband and my daughter for always being at my side and giving me strength to improve and become a professional. 3 INTRODUCTION My thesis topic was Health Tourist of Tungurahua .I had two months to prepared the tour that lasted two days and one night. My tour started on June first y finished on June second. The tour was prepared with some characteristics for the Switzerland people and based on what they would want to visit. When I knew my topic I started to look at some options and investigated; I was then able to give Edison some tour alternatives. -

ECUADOR EARTHQUAKES I Lq NATURAL DISASTER STUDIES Volume Five

PB93-186419 <> REPRODUCED BY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL TECHNICAL INFORMATION SERVICE SPRINGFIELD, VA. 22161 I, f J, J~ ITI mLt THE MARCH 5, 1987, ECUADOR EARTHQUAKES I lQ NATURAL DISASTER STUDIES Volume Five THE MARCH 5, 1987, ECUADOR EARTHQUAKES MASS WASTING AND SOCIOECONOMIC EFFECTS Study Team: Thomas O'Rourke, School of Civil and Envi ronmental Engineering, Cornell University, Robert L. Schuster (Team Leader and Tech Ithaca, New York nical Editor), Branch of Geologic Risk As sessment, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Contributing Authors: Colorado Jose Egred, Instituto Geoffsico, Escuela Patricia A. Bolton, Battelle Institute, Seattle, Politecnica Nacional, Quito, Ecuador Washington Alvaro F. Espinosa, Branch of Geologic Risk Louise K. Comfort, Graduate School of Pub Assessment, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, lic and International Affairs, University of Pitts Colorado burgh, Pennsylvania Manuel Garda-Lopez, Departamento de Esteban Crespo, School of Civil and Environ Ingenierfa Civil, Universidad Nacional de mental Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, Colombia, Bogota New York Minard L. Hall, Instituto Geofisico, Escuela Alberto Nieto, Department of Geology, Uni Politecnica Nacional, Quito, Ecuador versity of Illinois, Urbana Galo Plaza-Nieto, Departamento de Geotecnica, Kenneth J. Nyman, School of Civil and Envi Escuela Politecnica Nacional, Quito, Ecuador ronmental Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York Hugo Yepes, Instituto Geofisico, Escuela Politecnica Nacional, Quito, Ecuador For: Committee on Natural Disasters Division of Natural Hazard Mitigation Commission on Engineering and Technical Systems National Research Council NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS Washington, D.C. 1991 id NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. -

Counting on Forests and Accounting for Forest Contributions in National

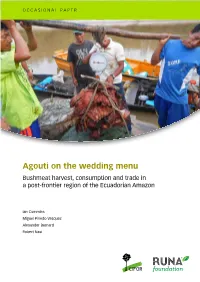

OCCASIONAL PAPER Agouti on the wedding menu Bushmeat harvest, consumption and trade in a post-frontier region of the Ecuadorian Amazon Ian Cummins Miguel Pinedo-Vasquez Alexander Barnard Robert Nasi OCCASIONAL PAPER 138 Agouti on the wedding menu Bushmeat harvest, consumption and trade in a post-frontier region of the Ecuadorian Amazon Ian Cummins Runa Foundation Miguel Pinedo-Vasquez Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) Earth Institute Center for Environmental Sustainability (EICES) Alexander Barnard University of California Robert Nasi Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) Occasional Paper 138 © 2015 Center for International Forestry Research Content in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN 978-602-387-009-7 DOI: 10.17528/cifor/005730 Cummins I, Pinedo-Vasquez M, Barnard A and Nasi R. 2015. Agouti on the wedding menu: Bushmeat harvest, consumption and trade in a post-frontier region of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Occasional Paper 138. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR. Photo by Alonso Pérez Ojeda Del Arco Buying bushmeat for a wedding CIFOR Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede Bogor Barat 16115 Indonesia T +62 (251) 8622-622 F +62 (251) 8622-100 E [email protected] cifor.org We would like to thank all donors who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Fund. For a list of Fund donors please see: https://www.cgiarfund.org/FundDonors Any views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of CIFOR, the editors, the authors’ institutions, the financial sponsors or the reviewers. -

ECUADOR Ecuador Is a Constitutional Republic with a Population Of

ECUADOR Ecuador is a constitutional republic with a population of approximately 14.3 million. In 2008 voters approved a referendum on a new constitution, which became effective in October of that year, although many of its provisions continued to be implemented. In April 2009 voters reelected Rafael Correa for his second presidential term and chose members of the National Assembly in elections that were considered generally free and fair. Security forces reported to civilian authorities. The following human rights problems continued: isolated unlawful killings and use of excessive force by security forces, sometimes with impunity; poor prison conditions; arbitrary arrest and detention; corruption and other abuses by security forces; a high number of pretrial detainees; and corruption and denial of due process within the judicial system. President Correa and his administration continued verbal and legal attacks against the independent media. Societal problems continued, including physical aggression against journalists; violence against women; discrimination against women, indigenous persons, Afro- Ecuadorians, and lesbians and gay men; trafficking in persons and sexual exploitation of minors; and child labor. RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life The government or its agents did not commit any politically motivated killings; however, there continued to be credible reports that security forces used excessive force and committed isolated unlawful killings. On April 23, the government's Unit for the Fight against Organized Crime released a report exposing the existence of a gang of hit men composed of active-duty police. The report stated that police were part of a "social cleansing group" that killed delinquents in Quevedo, Los Rios Province. -

Volcanic Eruption

ECUADOR: Appeal No. MDREC002 30 August 2006 VOLCANIC ERUPTION The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in 185 countries. In Brief Operations Update no. 1; Period covered: 23 August to 29 August, 2006; Appeal target: CHF 632,064 (USD 514,753 OR EUR 400,384); see the operational summary below for a list of current donors to the Appeal. (The Contributions List is currently being compiled and will be available on the website shortly). Appeal history: · Launched on 23 August 2006 for CHF 632,064 (USD 514,753 OR EUR 400,384) for 5 months to assist 5,000 beneficiaries; (1,000 beneficiary families) · Final Report is therefore due on 23 April 2007. · Disaster Relief Emergency Funds (DREF) allocated: CHF 85,000 (USD 68,079 or EUR 54,092). Operational Summary: The Ecuadorian Red Cross (ERC) has carried out surveys and identified 1,000 beneficiary families in the Districts of Patate and Pelileo in the Province of Tungurahua and of Penipe and Guano in the Province of Chimborazo, which it seeks to assist under the Plan of Action. During the reporting period, agreements were signed with partners in order to implement health activities whereby medical care will be provided in the affected communities through a mobile medical team. Water analysis was carried out by the ERC in coordination with partners including OXFAM and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and more detailed results of these assessments are awaited in order to define interventions in the area of water and sanitation. -

Bats of the Tropical Lowlands of Western Ecuador

Special Publications Museum of Texas Tech University Number 57 25 May 2010 Bats of the Tropical Lowlands of Western Ecuador Juan P. Carrera, Sergio Solari, Peter A. Larsen, Diego F. Alvarado, Adam D. Brown, Carlos Carrión B., J. Sebastián Tello, and Robert J. Baker Editorial comment. One extension of this collaborative project included the training of local students who should be able to continue with this collaboration and other projects involving Ecuadorian mammals. Ecuador- ian students who have received or are currently pursuing graduate degrees subsequent to the Sowell Expeditions include: Juan Pablo Carrera (completed M.A. degree in Museum Science at Texas Tech University (TTU) in 2007; currently pursuing a Ph.D. with Jorge Salazar-Bravo at TTU); Tamara Enríquez (completed M.A. degree in Museum Science at TTU in 2007, Robert J. Baker (RJB), major advisor); René M. Fonseca (received a post- humous M.S. degree from TTU in 2004, directed by RJB); Raquel Marchán-Rivandeneira (M.S. degree in 2008 under the supervision of RJB; currently pursuing a Ph.D. at TTU directed by Richard Strauss and RJB); Miguel Pinto (M.S. degree at TTU in 2009; currently pursuing a Ph.D. at the Department of Mammalogy and Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics at the American Museum of Natural History, City University of New York); Juan Sebastián Tello (completed a Licenciatura at Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (PUCE) in 2005 with Santiago Burneo; currently pursuing a Ph.D. at Louisiana State University directed by Richard Stevens); Diego F. Alvarado (pursuing a Ph.D. at University of Michigan with L. -

Antonio Preciado and the Afro Presence in Ecuadorian Literature

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2013 Antonio Preciado and the Afro Presence in Ecuadorian Literature Rebecca Gail Howes [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the African History Commons, Latin American History Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Latin American Literature Commons, Modern Languages Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Howes, Rebecca Gail, "Antonio Preciado and the Afro Presence in Ecuadorian Literature. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1735 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Rebecca Gail Howes entitled "Antonio Preciado and the Afro Presence in Ecuadorian Literature." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. Michael Handelsman, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Óscar Rivera-Rodas, Dawn Duke, Chad Black Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Antonio Preciado and the Afro Presence in Ecuadorian Literature A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Rebecca Gail Howes May 2013 DEDICATION To my parents, William and Gail Howes. -

Sangay Volcano

Forecast based Action by the DREF Forecast based early action triggered in Ecuador: Volcanic Ash Dispersion- Sangay volcano EAP2019EC001 Ash fall dispersion model corresponding to Sangay's current activity The areas with higher probability of ash fall are shown. Source: Geophysical Institute of the National Polytechnic (Instituto Geofísico de la Politécnica Nacional - IGEPN). 1,000 families to be assisted 246,586.27 budget in Swiss francs (200,571.46 Swiss francs available) Locations: Rural communities in the cantons of Alausí, Guamote, Pallatanga and Cumanda. The communities will be defined based on the analysis of information issued in the National Society's situation reports. General overview The Ecuadorian Red Cross (ERC) has activated its Early Action Protocol for Volcanic Ashfall. Since June 2020, the eruptive process of Sangay volcano has registered high to very high levels of activity. According to the report issued by the Geophysical Institute of the National Polytechnic (IGEPN), in the early morning of 20 September 2020, the volcano registered a significant increase in the volcano’s internal and external activity. From 04h20 (GMT-5), the records indicate the occurrence of explosions and ash emissions that are more energetic and 1 | P a g e stronger than those registered in previous months. From 04h00, according to the IGEPN satellite image, a large ash cloud has risen to a height of more than 6 to 10 km above the volcano's crater. The highest part of the cloud is registered to the eastern sector while the lowest part is located west of the volcano. According to tracking and monitoring, ash dispersion models indicate the high probability of ash fall in the provinces of Chimborazo, Bolívar, Guayas, Manabí, Los Ríos and Santa Elena. -

Indigenous Peoples and State Formation in Modern Ecuador

1 Indigenous Peoples and State Formation in Modern Ecuador A. KIM CLARK AND MARC BECKER The formal political system is in crisis in Ecuador: the twentieth century ended with a four-year period that saw six different governments. Indeed, between 1997 and 2005, four of nine presidents in Latin America who were removed through irregular procedures were in Ecuador.1 Sociologist Leon Zamosc calls Ecuador “one of the most, if not the most, unstable country in Latin America.”2 At the same time, the Ecuadorian Indian movement made important gains in the last decade of the twentieth century, and for at least some sectors of society, at the turn of the twenty-first century had more pres- tige than traditional politicians did. The fact that Ecuador has a national-level indigenous organization sets it apart from other Latin American countries. National and international attention was drawn to this movement in June 1990, when an impressive indigenous uprising paralyzed the country for sev- eral weeks. Grassroots members of the Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador (CONAIE, Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador) marched on provincial capitals and on Quito, kept their agricul- tural produce off the market, and blocked the Pan-American Highway, the country’s main north-south artery. The mobilization was organized to draw attention to land disputes in the Ecuadorian Amazon (Oriente) and highlands (Sierra), and ended when the government agreed to negotiate a 16-point agenda presented by CONAIE.3 Since 1990, Ecuadorian Indians have become increasingly involved in national politics, not just through “uprising politics,” but also through 1 © 2007 University of Pittsburgh Press. -

Volcano Preparedness

DREF Final Report Ecuador: Volcano Preparedness DREF operation MDREC010 Date issued: 20 July 2016 Operation manager: Pabel Angeles, Regional Disaster Point of Contact: Paola López - Management Coordinator – South America – International National Technical Response, Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) Ecuadorian Red Cross Operation start date: 7 December 2015 Date of disaster: 19 November 2015 Expected timeframe: 3 months and 3 Overall operation budget: 124,895 Swiss francs (CHF) weeks Number of people to be assisted: Number of people affected: 130,042 people 5,000 people (1,000 families). Host National Society presence (number of volunteers, staff, and branches): Ecuadorian Red Cross (ERC) national headquarters; 24 provincial boards; 110 branches; 8,000 volunteers; and 200 staff members. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Relevant state ministries; Risk Management Secretariat; relevant provincial and municipal governments; the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF); World Food Programme (WFP); and Plan International. <Click here to view the final financial report and here for contact details> A. Situation Analysis A.1 Description of the disaster After the increase in activity of the Tungurahua Volcano in November 2015, another increase in activity was detected in early March 2016; due to the increased activity, the operation was extended for another 3 weeks. The emergency began in mid-November when emissions reached 3,500 metres above the crater level and began drifting northwest. The falling ash affected several villages located on the slopes of the volcano, as well as several cantons in the provinces of Tungurahua and Chimborazo.