“Our Victims Define Our Borders”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Tavole Statistiche Fuori Testo

Tavole statistiche Elenco delle tavole statistiche fuori testo Tirature e vendite complessive dei giornali quotidiani per area di diffusione e per categoria (2003-2004-2005) Provinciali ....................................................................................................................................................... Tavola I Regionali .......................................................................................................................................................... Tavola II Pluriregionali ............................................................................................................................................... Tavola III Nazionali .......................................................................................................................................................... Tavola IV Economici ....................................................................................................................................................... Tavola V Sportivi .............................................................................................................................................................. Tavola VI Politici ................................................................................................................................................................. Tavola VII Altri ...................................................................................................................................................................... -

Aurisina Limestone in the Roman Age: from Karst Quarries to the Cities of the Adriatic Basin

Aurisina Limestone in the Roman Age: from Karst Quarries to the Cities of the Adriatic Basin Previato, Caterina Source / Izvornik: ASMOSIA XI, Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone, Proceedings of the XI International Conference of ASMOSIA, 2018, 933 - 939 Conference paper / Rad u zborniku Publication status / Verzija rada: Published version / Objavljena verzija rada (izdavačev PDF) https://doi.org/10.31534/XI.asmosia.2015/08.12 Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:123:205217 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-11 Repository / Repozitorij: FCEAG Repository - Repository of the Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy, University of Split ASMOSIA PROCEEDINGS: ASMOSIA I, N. HERZ, M. WAELKENS (eds.): Classical Marble: Geochemistry, Technology, Trade, Dordrecht/Boston/London,1988. e n ASMOSIA II, M. WAELKENS, N. HERZ, L. MOENS (eds.): o t Ancient Stones: Quarrying, Trade and Provenance – S Interdisciplinary Studies on Stones and Stone Technology in t Europe and Near East from the Prehistoric to the Early n Christian Period, Leuven 1992. e i ASMOSIA III, Y. MANIATIS, N. HERZ, Y. BASIAKOS (eds.): c The Study of Marble and Other Stones Used in Antiquity, n London 1995. A ASMOSIA IV, M. SCHVOERER (ed.): Archéomatéiaux – n Marbres et Autres Roches. Actes de la IVème Conférence o Internationale de l’Association pour l’Étude des Marbres et s Autres Roches Utilisés dans le Passé, Bordeaux-Talence 1999. e i d ASMOSIA V, J. HERRMANN, N. HERZ, R. NEWMAN (eds.): u ASMOSIA 5, Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone – t Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference of the S Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in y Antiquity, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, June 1998, London r 2002. -

And Bernardo Bertolucci's 1900

The “Betrayed Resistance” in Valentino Orsini’s Corbari (1970) and Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1900 (1976) Dominic Gavin The connections between Italian film and history have been the object of renewed attention in recent years. A number of studies have provided re-readings of Italian cinema, especially from the perspective of public memory. Charting the interrelations of cinema, the public use of history, and historiography, these studies include reevaluations of the cinema of the Resistance, the war film, the Holocaust and the Fascist dictatorship.1 The ongoing debates over Resistance memory in particular—the “never-ending liberation,” in the words of one historian—have provided a motive for reconsidering popular cultural productions as vehicles of collective perceptions of the past.2 If Italian film studies came relatively late to the issues of cinema and public memory, this approach has now become mainstream.3 In this essay, I am concerned with films on the Resistance during the 1970s. These belong to a wider grouping of contemporary cinematic productions that deal with the Fascist dictatorship and antifascism. These films raise a series of critical questions. How did the general film field contribute to the wider processing of historical memory, and how did it relate to political violence in Italy?4 To what extent did the work of Italian filmmakers participate in the “new discourse” of international cinema in the 1970s concerning the treatment of Nazism and the occupation,5 or to what extent were filmmakers engaged in reaffirming populist -

Military Entrepreneurship in the Shadow of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949)

JPR Men of the Gun and Men of the State: Military Entrepreneurship in the Shadow of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949) Spyros Tsoutsoumpis Abstract: The article explores the intersection between paramilitarism, organized crime, and nation-building during the Greek Civil War. Nation-building has been described in terms of a centralized state extending its writ through a process of modernisation of institutions and monopolisation of violence. Accordingly, the presence and contribution of private actors has been a sign of and a contributive factor to state-weakness. This article demonstrates a more nuanced image wherein nation-building was characterised by pervasive accommodations between, and interlacing of, state and non-state violence. This approach problematises divisions between legal (state-sanctioned) and illegal (private) violence in the making of the modern nation state and sheds new light into the complex way in which the ‘men of the gun’ interacted with the ‘men of the state’ in this process, and how these alliances impacted the nation-building process at the local and national levels. Keywords: Greece, Civil War, Paramilitaries, Organized Crime, Nation-Building Introduction n March 1945, Theodoros Sarantis, the head of the army’s intelligence bureau (A2) in north-western Greece had a clandestine meeting with Zois Padazis, a brigand-chief who operated in this area. Sarantis asked Padazis’s help in ‘cleansing’ the border area from I‘unwanted’ elements: leftists, trade-unionists, and local Muslims. In exchange he promised to provide him with political cover for his illegal activities.1 This relationship that extended well into the 1950s was often contentious. -

A Comparative Analysis of Media Freedom and Pluralism in the EU Member States

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT C: CITIZENS' RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS CIVIL LIBERTIES, JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS A comparative analysis of media freedom and pluralism in the EU Member States STUDY Abstract This study was commissioned by the European Parliament's Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the LIBE Committee. The authors argue that democratic processes in several EU countries are suffering from systemic failure, with the result that the basic conditions of media pluralism are not present, and, at the same time, that the distortion in media pluralism is hampering the proper functioning of democracy. The study offers a new approach to strengthening media freedom and pluralism, bearing in mind the different political and social systems of the Member States. The authors propose concrete, enforceable and systematic actions to correct the deficiencies found. PE 571.376 EN ABOUT THE PUBLICATION This research paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) and commissioned, overseen and published by the Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs. Policy Departments provide independent expertise, both in-house and external, to support EP committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic scrutiny over EU external and internal policies. To contact the Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs or to subscribe -

Dangerous Liaisons

University of Huddersfield Repository Davies, Peter J. Dangerous liaisons Original Citation Davies, Peter J. (2004) Dangerous liaisons. Pearson Longman, London, pp. 9-29. ISBN 978- 0582772274 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/5522/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Chapter 1 MEANING AND VARIETIES Give me your watch and I’ll tell you the time. German view of collaboration[1] The Nazis’ newspaper in Jersey, Insel Zeitung, was keen to publicise the fact that the islanders were enthusiastic about the occupation and keen to be Germanised: In the course of a band concert given in the Royal Square and largely attended by children and young people, at a given moment, the bandmaster attracted the attention of his juvenile audience by calling out that he had a question to ask them. -

Rapporto 2019 Sull'industria Dei Quotidiani in Italia

RAPPORTO 2019 RAPPORTO RAPPORTO 2019 sull’industria dei quotidiani in Italia Il 17 dicembre 2012 si è ASSOGRAFICI, costituito tra AIE, ANES, ASSOCARTA, SLC-‐CGIL, FISTEL-‐CISL e UILCOM, UGL sull’industria dei quotidiani in Italia CHIMICI, il FONDO DI ASSISTENZA SANITARIA INTEGRATIVA “Salute Sempre” per il personale dipendente cui si applicano i seguenti : CCNL -‐CCNL GRAFICI-‐EDITORIALI ED AFFINI -‐ CCNL CARTA -‐CARTOTECNICA -‐ CCNL RADIO TELEVISONI PRIVATE -‐ CCNL VIDEOFONOGRAFICI -‐ CCNL AGIS (ESERCENTI CINEMA; TEATRI PROSA) -‐ CCNL ANICA (PRODUZIONI CINEMATOGRAFICHE, AUDIOVISIVI) -‐ CCNL POLIGRAFICI Ad oggi gli iscritti al Fondo sono circa 103 mila. Il Fondo “Salute Sempre” è senza fini di lucro e garantisce agli iscritti ed ai beneficiari trattamenti di assistenza sanitaria integrativa al Servizio Sanitario Nazionale, nei limiti e nelle forme stabiliti dal Regolamento Attuativo e dalle deliberazioni del Consiglio Direttivo, mediante la stipula di apposita convenzione con la compagnia di assicurazione UNISALUTE, autorizzata all’esercizio dell’attività di assicurazione nel ramo malattia. Ogni iscritto potrà usufruire di prestazioni quali visite, accertamenti, ricovero, alta diagnostica, fisioterapia, odontoiatria . e molto altro ancora Per prenotazioni: -‐ www.unisalute.it nell’area riservata ai clienti -‐ telefonando al numero verde di Unisalute -‐ 800 009 605 (lunedi venerdi 8.30-‐19.30) Per info: Tel: 06-‐37350433; www.salutesempre.it Osservatorio Quotidiani “ Carlo Lombardi ” Il Rapporto 2019 sull’industria dei quotidiani è stato realizzato dall’Osservatorio tecnico “Carlo Lombardi” per i quotidiani e le agenzie di informazione. Elga Mauro ha coordinato il progetto ed ha curato la stesura dei testi, delle tabelle e dei grafici di corredo e l’aggiornamento della Banca Dati dell’Industria editoriale italiana La versione integrale del Rapporto 2019 è disponibile sul sito www.ediland.it Osservatorio Tecnico “Carlo Lombardi” per i quotidiani e le agenzie di informazione Via Sardegna 139 - 00187 Roma - tel. -

Il Parlamento E L'evoluzione Degli Strumenti Della Legislazione

Tavola rotonda su IL PARLAMENTO E L’EVOLUZIONE DEGLI STRUMENTI DELLA LEGISLAZIONE promossa dal Comitato per la legislazione in conclusione del secondo ciclo di Presidenza 12 gennaio 2010 Sala della Lupa Camera dei deputati Roma La tavola rotonda, promossa dal Comitato per la legislazione a conclusione del secondo ciclo di presidenza, riunisce personalità politiche che rivestono, o hanno rivestito, diverse posizioni di responsabilità nello svolgimento del processo legislativo. La tavola rotonda pone al centro della riflessione il ruolo fondamentale del Presidente di Assemblea, nell’esperienza dei presidenti della Camera dei deputati che si sono succeduti nelle ultime quattro legislature e che hanno tutti dovuto far fronte a rilevanti difficoltà nel procedimento legislativo. Nelle stesse quattro legislature il Comitato per la legislazione, istituito nel gennaio 1998, ha operato a supporto di tale impegnativa funzione presidenziale, svolgendo i suoi compiti di vigilanza sulla qualità dei testi legislativi, con particolare riferimento alle forme prevalenti di legislazione (deleghe e decreti legge). Presso entrambe le Camere, le Commissioni Affari costituzionali svolgono anch’esse un delicato ruolo di controllo con riferimento agli aspetti di costituzionalità, che investe non solo i contenuti ma anche le procedure e il sistema delle competenze. Inoltre, le due Commissioni sono al centro dei processi di riforma costituzionale. Sul versante governativo, il Ministro per i rapporti con il Parlamento svolge un ruolo altrettanto complesso nel misurarsi con le difficoltà del processo legislativo collegando un doppio fronte: l’insieme dei rapporti interni al Governo e quello con i diversi organi parlamentari in entrambe le Camere. Come base della discussione si offrono le analisi delle tendenze della legislazione elaborate di recente nell’ambito del Comitato: la “nota di sintesi” del Rapporto sulla legislazione 2009, edito dalla Camera dei deputati, e “Tendenze e problemi della decretazione d’urgenza”, presentato al Comitato per la legislazione il 12 novembre 2009. -

Hitler's War Aims

Hitler’s War Aims Gerhard Hirschfeld Between 1939 and 1945, the German Reich dominated large parts of Europe. It has been estimated that by the end of 1941 approximately 180 million non-Germans lived under some form of German occupation. Inevitably, the experience and memory of the war for most Europeans is therefore linked less with military action and events than with Nazi (i.e. National Socialist) rule and the manifold expressions it took: insecurity and unlawfulness, constraints and compulsion, increasing difficult living conditions, coercive measures and arbitrary acts of force, which ultimately could threaten the very existence of peoples. Moreover, for those millions of human beings whose right to existence had been denied for political, social, or for – what the Nazis would term – ‘racial motives’ altogether, the implications and consequences of German conquest and occupation of Europe became even more oppressive and hounding.1 German rule in Europe during the Second World War involved a great variety of policies in all countries under more or less permanent occupation, determined by political, strategically, economical and ideological factors. The apparent ‘lack of administrative unity’ (Hans Umbreit) in German occupied Europe was often lamented but never seriously re-considered.2 The peculiar structure of the German ‘leader-state’ (Fuehrerstaat) and Hitler's obvious indifference in all matters of administration, above, his well known indecisiveness in internal matters of power, made all necessary changes, except those dictated by the war itself, largely obsolete. While in Eastern Europe the central purpose of Germany's conquest was to provide the master race with the required ‘living space’ (Lebensraum) for settlement as well as human and economic resources for total exploitation, the techniques for political rule and economic control appeared less brutal in Western Europe, largely in accordance with Hitler’s racial and ideological views. -

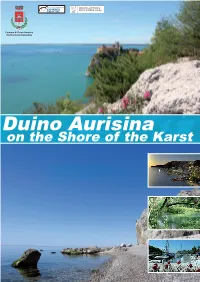

Duino Aurisina on the Shore of the Karst Duino Aurisina, on the Shores of the Karst a Unique Range of Tourism Experiences

Duino Aurisina on the Shore of the Karst duino aurisina, on the shores of the karst A unique range of tourism experiences. From the coast to the Carso plateau, there are many quality attractions: organised beaches with all facilities, historical castels, places of artistic value, agritourism facilities, wineries, hiking trails and paths among the pine woods and oak woods thet from one of the most unique and fascinating landscapes of the Northern Adriatic area. Come and discover it! for information: Comune di Duino Aurisina Ph. +39 040 2017372 [email protected] www.comune.duino-aurisina.ts.it IAT Sistiana (stagionale) Ph. +39 040 299166 [email protected] www.marecarso.it 120 km motorway drive from Venice - 15 km from trieste www.falesiediduino.it a few kilometres from ronchi dei Legionari airport TERRITORy Duino aurisina has always been a bridge between different worlds. Located at the northernmost extreme of the adriatic, it is a gateway between the east and the west as well as between the mediterranean and Central Europe. no wonder the area surrounding the springs of the timavo river, a unique river running for the most part underground, has been a place of worship for the longest time and also the most important local port until the mid-XVi century. in more recent times the worst horrors of the war were witnessed here between 1915 and 1917, when the austro-Hungarian and italian armies faced off on mount Grmada, leaving behind dozens of thousands of victims and a devastated land. now, with geopolitical conditions drastically changed, it has become one of the best locations to live in or just visit. -

Virtual Spring Fayre Red Zone Restrictions Book Club EJSU

Welcome to the April Newsletter! With Minimum Manning and Easter fast approaching this newsletter is coming to you a little bit early! March has been a funny one with zones changing and children returning to Virtual School. Hopefully the warmer weather of April will bring a bit of light relief and the chance to get back out of our homes and into the wider community once again. We have the Virtual Spring Fayre competitions running for the beginning of the month which I hope that the whole con- tingent will get involved in, there’s something there for everyone. Also, with changes to EJSU regulations there is a big push for more volunteers for events and groups. Further details for all of this can be found further down the newsletter. I hope that everyone enjoys their leave over the Easter period and that the Easter Bunny is generous this year Take care and stay safe. Virtual Spring Fayre I have previously sent out details of the Spring Fayre Com- petitions, I will include them again at the bottom of the Post newsletter. This is an opportunity for the whole communi- ty to be involved in some light hearted fun, with the added As with the last newsletter, currently there is still a parcel bonus of some prizes! There are categories that are just ban in place from BFPO Northolt for our location. Letters for the children, but plenty of others for adults as well. The entry deadline is April 8, the panel of EJSU CLO judges will can still be sent back to the UK through the BFPO system announce the winners in the week commencing April 12. -

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: a Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: A Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944 ARGYRIOS MAMARELIS Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy The European Institute London School of Economics and Political Science 2003 i UMI Number: U613346 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U613346 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 9995 / 0/ -hoZ2 d X Abstract This thesis addresses a neglected dimension of Greece under German and Italian occupation and on the eve of civil war. Its contribution to the historiography of the period stems from the fact that it constitutes the first academic study of the third largest resistance organisation in Greece, the 5/42 regiment of evzones. The study of this national resistance organisation can thus extend our knowledge of the Greek resistance effort, the political relations between the main resistance groups, the conditions that led to the civil war and the domestic relevance of British policies.