Rebaking the Pie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seinfeld, the Movie an Original Screenplay by Mark Gavagan Contact

Seinfeld, The Movie an original screenplay by Mark Gavagan based on the "Seinfeld" television series by Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld contact: Cole House Productions (201) 320-3208 BLACK SCREEN: TEXT: "One year later ..." TEXT FADES: DEPUTY (O.S.) Well folks. You've paid your debt to society. Good luck and say out of trouble. FADE IN: EXT. LOWELL MASSACHUSETTS JAIL -- MORNING ROLL CREDITS. JERRY, GEORGE and ELAINE look impatient as they stand empty- handed, waiting for something. The DEPUTY walks back towards the jail building behind them. CUT TO: INT. LOWELL MASSACHUSETTS JAIL KRAMER is surrounded by teary-eyed guards and inmates. They love him. He's carrying a metal cafeteria tray covered with signatures, as well as scores of cards, notes and letters. Several in the crowd hug KRAMER. CUT TO: EXT. LOWELL MASSACHUSETTS JAIL KRAMER stumbles as he walks up to GEORGE, ELAINE and JERRY. CUT TO: EXT. SOMEWHERE IN RURAL MASSACHUSETTS -- DAY We see an ugly old school bus at a dead stop with the flashers on. "LARRY'S NYC BUS SERVICE" is painted sloppily on the side. An extremely old man herds dozens of stubborn sheep across the road. He's moving at an impossibly slow pace. CUT TO: INT. OLD SCHOOL BUS JERRY, GEORGE and ELAINE are sitting in bus's original kid- sized bench seats. They look bored and uncomfortable. 2. Cheerful KRAMER is in the front row chatting with the DRIVER and pointing at the animals outside. CUT TO: INT. HALLWAY IN FRONT OF JERRY'S APARTMENT -- LATER KRAMER & JERRY walk wearily towards their doors. -

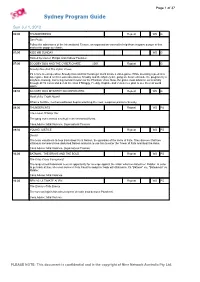

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 37 Sydney Program Guide Sun Jul 1, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Sun Probe Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:00 SCOOBY DOO AND THE CYBER CHASE 2001 Repeat G Scooby Doo And The Cyber Chase It's a race to escape when Scooby-Doo and his friends get stuck inside a video game. While sneaking a peek at a laser game based on their own adventures, Scooby and the Mystery Inc. gang are beamed inside the program by a mayhem-causing, menacing monster known as the Phantom Virus. Now, the game must advance successfully through all 10 levels and defeat the virus if Shaggy, Freddy, Daphne and Velma ever plan to see the real world again. 08:30 SCOOBY DOO MYSTERY INCORPORATED Repeat WS G Howl of the Fright Hound When a horrible, mechanized beast begins attacking the town, suspicion points to Scooby. 09:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG The Forest Of Magi Oar The gang come across a school in an enchanted forest. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes 09:30 YOUNG JUSTICE Repeat WS PG Denial The team volunteers to help track down Kent Nelson, the guardian of the Helm of Fate. They discover that two villainous sorcerers have abducted Nelson and plan to use him to enter the Tower of Fate and steal the Helm. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes 10:00 BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD Repeat WS PG The Criss Cross Conspiracy! The long-retired Batwoman sees an opportunity for revenge against the villain who humiliated her: Riddler. -

8 TV Power Games: Friends and Law & Order

8 TV Power Games: Friends and Law & Order There is no such thing as a one-man show | at least not in television: one feature that all TV shows have in common is the combination of a large number of diverse contributors: producers, scriptwriters, actors, and so on. This is illustrated in Exhibit 8.1, which depicts the links between key contributors to the making and selling of a TV show. Solid lines repre- sent some form of contractual relationship, whereas dashed lines represent non-contractual relationships of relevance for value creation and value distribution. As is the case with movies, pharmaceutical drugs, and other products, the distribution of TV show values is very skewed: many TV shows are worth relatively little, whereas a few shows generate a very high value: For example, at its peak Emmy Award-winning drama ER fetched $13 million per episode.1 How does the value created by successful shows get divided among its various contrib- utors, in particular actors, producers and networks? Who gets the biggest slice of the big pie? In this chapter, I address this question by looking at two opposite extreme cases in terms of relative negotiation power: Law & Order and Friends. Law & Order | and profits The legal drama series Law & Order was first broadcast on NBC on September 13, 1990. (The pilot episode, produced in 1988, was intended for CBS, but the network rejected it, just as Fox did later, in both cases because the show did not feature any \breakout" characters.) By the time the last show aired on May 24, 2010, it was the longest-running crime drama on American prime time TV. -

New York City

New LocalYork Cusine City Use the hashtag #weeklander on Instagram New York Style JOHNS OF BLEEKER STREET (PIZZA) KATZ DELI (DELI) Founded in 1929 it is one of the oldest pizzerias in the Founded in 1888, Katz Deli is known for thier corned city. Brick oven fired pizza sold by the pie. beef and pastrami. Featured in “When Harry Met Sally” www.johnsbrickovenpizza.com www.katzdelicatssen.com JOE’S PIZZA (PIZZA) THE HALAL GUYS (MEDITERRANEAN) Established in 1975, Joe’s Pizza is known for selling Started as a hot dog cart in 1990. #3 more reviewed pizza by the slice. eatery in the U.S. Known for Chicken Gyros. www.joespizzanyc.com www.thehalalguys.com PAPAYA KING (HOT DOGS) BOUCHERIE (FRENCH) Hailed by Julia Childs as the best hot dog in the city. A traditional French brasserie and stakehouse. Great Founded in 1932, Papaya King is known for their hot lunch selection. dogs and tropical drinks. www.boucherie.nyc www.papayaking.com NATHAN’S FAMOUS HOT DOGS (HOT DOGS) Nathan’s started as a humble hot dog cart on Coney Famous Eats Island in 1916. The original Coney Island dog. TOM’S RESTAURANT (SEINFELD) www.nathansfamous.com Classic diner style eatery known for its feature in the ABSOLUTE BAGELS (BAGELS) sitcom “Seinfeld”. Serving brunch 7 days a week. www.tomsrestaurant.net Rated New York’s absolute best bagel. CAFE LALO (YOU’VE GOT MAIL) BEST BAGEL & COFFEE (BAGELS) The most famous cafe in NYC. Featured in “You’ve Got Hand rolled bagels baked daily. Mail”. Popular place to stop for dessert and cappuccino. -

Dealer of the Year

MSADA, One McKinley Square, Sixth Floor, Boston, MA 02109 FIRST CLASS MAIL MASSACHUSETTS US POSTAGE PAID BOSTON, MA PERMIT NO. 216 AUTODEALER March 2010 • Vol. 23, No. 3 The official publication of the Massachusetts State Automobile Dealers Association, Inc DEALER OF THE YEAR Rick INSIDE: •NADA Convention •Toyota Damage Mastria Continues MASSACHUSETTS AUTODEALER The official publication of the Massachusetts State Automobile Dealers Association, Inc STAFF DIRECTOry Robert O’Koniewski, Esq. Executive Vice President [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Irene Varao Director of Administration [email protected] Tricia White 4 FROM THE PRESIDENT: The Damage Continues Accounting and Membership Manager [email protected] 6 POLITICAL ACTION: No Lifeline Yet Sam Poikail Information Technology & 8 COVER STORY: Membership Information Manager [email protected] Rick Mastria – Dealer of the Year Tom Nash Editorial Coordinator 12 ACCOUNTING: Vehicle Service [email protected] Karen Kast-McBride Contracts Administrative Coordinator [email protected] 13 LEGAL: Beware of Manufacturers Nicole Ventosi Bearing Gifts Administrative Assistant [email protected] 14 NADA Convention Report Subscriptions provided annually to Massachusetts dealers. All address changes 19 TRUCK CORNER: Deconstructing the Alphabet Soup should be submitted to: MSADA by e-mail: [email protected] 20 NEWS From Around the Horn Postmaster: Send address change to: 25 NADA UPDATE: Customer Safety Testimony One McKinley Square, Sixth Floor Boston, MA 02109 Auto Dealer is published by the Massachusetts State Automobile Dealers Association, Inc. to provide information about the Bay State auto retail industry and news of MSADA and its membership. www.msada.org Massachusetts Auto Dealer MARCH 2010 4 from the PRESIDENT by James G. -

“Peace of the Pie” Drive-By Stewardship Event

NOVEMBER 2020 “Peace Of The Pie” Drive-by Stewardship Event November 8 at 11:30am in the church parking lot This year's stewardship campaign is headlined "The Great Loves: love of creation, love of neighbor, and love of children.” The biblical inspiration comes from 1 John 4:7, "Beloved, let us love one another because love is from God; everyone who loves is born of God and knows God.” Pledge packets have been mailed out, and we invite you to drive by the church on November 8 to turn in your 2021 pledge cards and receive a free slice of fresh pie! There will be a variety of pies to choose from, generously donated by Betty’s Pies and Rustic Inn. Thanks for all you do to help Peace keep being the church in so many ways during this unprecedented time. We ask for your continued support for our church family and all that it does to advance the gospel message of loving one another. Photos taken from our Fall Festival held on October 11, 2020. This event was in conjunction with our Stewardship Kick-Off where we served a drive-by sandwich lunch. Several outdoor games were offered such as a cake walk and pumpkin toss. Many thanks to our folk music group featuring Terrence Smith, Laura and Jeff Greensmith and friends. Some kids came in costume and many kids were able to see their mural piece in the VBS “Web Of Life” art project. Thanks to Sharon and the Children’s Ministry Team, the Stewardship Committee and others for putting on this fun event. -

The Barber (^Seinfeld) from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

:rhe Barber (Seinfeld) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of2 The Barber (^Seinfeld) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "The Barber" is theT2nd episode of the NBC sitcom Seinfeld.It is the eighth episode of the fifth "The Barber" season, and first aired on November ll,1993. Seínfeld episode Plot Episode no. Season 5 Episode 8 The episode begins with George at ajob Directed by Tom Cherones interview. His future employer, Mr. Tuttle, is cut Written by Andy Robin off mid-sentence by an important telephone call, and sends George away without knowing whether Production code 508 he has been hired or not. Mr. Tuttle told George Original air date November ll,1993 that one of the things that make George such an Guest actors attractive hire is that he can "understand everything immediately", so this leaves apuzzling situation. In Jerry's words: "If you call and ask if Wayne Knight as Newman Antony Ponzini as Enzo you have the job, you might lose the job." But if David Ciminello as Gino George doesn't call, he might have been hired and Michael Fairman as Mr. Penske he never know. George will decides that the best Jack Shearer as Mr. Tuttle course of action is to not call at all and to just "show up", pretending that he has been hired and Season 5 episodes start "work", all while Mr. Tuttle is out of town. The thought behind this was that if George has the September 1993 -May 1994 job, then everything will be fine; and if George uThe was not hired, then by the time Tuttle returns, he 1. -

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Šárka Tripesová The Anatomy of Humour in the Situation Comedy Seinfeld Bachelor‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph.D. 2010 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Šárka Tripesová ii Acknowledgement I would like to thank Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph.D. for the invaluable guidance he provided me as a supervisor. Also, my special thanks go to my boyfriend and friends for their helpful discussions and to my family for their support. iii Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 SEINFELD AS A SITUATION COMEDY 3 2.1 SEINFELD SERIES: THE REALITY AND THE SHOW 3 2.2 SITUATION COMEDY 6 2.3 THE PROCESS OF CREATING A SEINFELD EPISODE 8 2.4 METATHEATRICAL APPROACH 9 2.5 THE DEPICTION OF CHARACTERS 10 3 THE TECHNIQUES OF HUMOUR DELIVERY 12 3.1 VERBAL TECHNIQUES 12 3.1.1 DIALOGUES 12 3.1.2 MONOLOGUES 17 3.2 NON-VERBAL TECHNIQUES 20 3.2.1 PHYSICAL COMEDY AND PANTOMIMIC FEATURES 20 3.2.2 MONTAGE 24 3.3 COMBINED TECHNIQUES 27 3.3.1 GAG 27 4 THE METHODS CAUSING COMICAL EFFECT 30 4.1 SEINFELD LANGUAGE 30 4.2 METAPHORICAL EXPRESSION 32 4.3 THE TWIST OF PERSPECTIVE 35 4.4 CONTRAST 40 iv 4.5 EXAGGERATION AND CARICATURE 43 4.6 STAND-UP 47 4.7 RUNNING GAG 49 4.8 RIDICULE AND SELF-RIDICULE 50 5 CONCLUSION 59 6 SUMMARY 60 7 SHRNUTÍ 61 8 PRIMARY SOURCES 62 9 REFERENCES 70 v 1 Introduction Everyone as a member of society experiences everyday routine and recurring events. -

Articles and Their Chemical Composition Were Performed Rural Site

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 8831–8847, 2016 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/16/8831/2016/ doi:10.5194/acp-16-8831-2016 © Author(s) 2016. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Aerosol source apportionment from 1-year measurements at the CESAR tower in Cabauw, the Netherlands Patrick Schlag1,2, Astrid Kiendler-Scharr2, Marcus Johannes Blom3, Francesco Canonaco4, Jeroen Sebastiaan Henzing5, Marcel Moerman5, André Stephan Henry Prévôt4, and Rupert Holzinger1 1Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research Utrecht (IMAU), Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands 2Institute for Energy and Climate Research (IEK-8): Troposphere, Forschungszentrum Jülich, Jülich, Germany 3Energy Research Centre of the Netherlands (ECN), Petten, the Netherlands 4Laboratory of Atmospheric Chemistry, Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI), Villigen, Switzerland 5Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research (TNO), Utrecht, the Netherlands Correspondence to: Patrick Schlag ([email protected]) Received: 10 November 2015 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 15 December 2015 Revised: 17 June 2016 – Accepted: 28 June 2016 – Published: 19 July 2016 Abstract. Intensive measurements of submicron aerosol mospheric aging processes for aerosol concentration at this particles and their chemical composition were performed rural site. Due to the large secondary fraction, the reduction with an Aerosol Chemical Speciation Monitor (ACSM) at of particulate mass at this rural site is challenging on a local the Cabauw Experimental Site for Atmospheric Research scale. (CESAR) in Cabauw, the Netherlands, sampling at 5 m height above ground. The campaign lasted nearly 1 year from July 2012 to June 2013 as part of the EU-FP7- ACTRIS project (Q-ACSM Network). Including equivalent 1 Introduction black carbon an average particulate mass concentration of 9.50 µg m−3 was obtained during the whole campaign with Atmospheric aerosols have large impacts on the climate di- dominant contributions from ammonium nitrate (45 %), or- rectly by scattering and absorbing shortwave radiation. -

Mcbork Report Q1 2019 February 14, 2019

McBork Report Q1 2019 February 14, 2019 Seinfeld is one of my all-time favorite TV shows. I often find myself recalling some of the episodes during my own life. Recently, I was playing Trivial Pursuit with friends when a “stock market” question came up. The question was “What nation is not amused that its FTSE stock exchange name is pronounced footsie in the US?” I smiled, looked at my friends and said that I had this one. The answer was England. To my chagrin I was told that this was wrong and that the correct answer was Japan. I immediately remembered the Seinfeld episode when George was playing Trivial Pursuit with the “Bubble Boy”. The question on the show was “Who invaded Spain in the 8th century?” The Bubble Boy answered that it was the Moors, which was the correct answer, but the card had a misprint and said “Moops” instead. A fight ensued and the bubble surrounding the boy burst. Unlike George, my friends were a little more understanding and no bubbles were burst. They allowed us to look up the answer and we were awarded the blue piece of the pie. We all understood mistakes are made, even on a Trivia Pursuit game piece. Did the market make a mistake like Trivia Pursuit? News headlines such as “Worst December since the Great Depression” or “Worst Year for Stocks in a Decade” can really scare an investor. Both headlines are true, but we have to put them in perspective. Since the low in the S&P 500 Index a decade ago, it rose 341% to its all-time high in September. -

DOT State of Wisconsin Highway Safety Plan with Appendix 2017

HIGHWAY SAFETY PLAN STATE OF WISCONSIN FFY 2017 Scott Walker GOVERNOR OF WISCONSIN Mark Gottlieb, P.E. GOVERNOR’S REPRESENTATIVE FOR HIGHWAY SAFETY SECRETARY, WISCONSIN DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION David Pabst HIGHWAY SAFETY COORDINATOR STATE OF WISCONSIN FFY 2017 HIGHWAY SAFETY PLAN State of Wisconsin Federal Fiscal Year 2017 Highway Safety Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Highway Safety Plan 1 • Mission Statement • Executive Summary • Highway Safety Planning Process and Timeline • State-level Problem Identification II. Highway Safety Plan by Program Area 9 Planning & Administration 11 Occupant Protection Program 13 Impaired Driving Program 19 Police Traffic Program 27 Traffic Records Improvement Plan 31 EMS Improvement Plan 35 Motorcyclist Safety Program 39 Pedestrian and Bicyclist Safety Program 45 Community Traffic Safety Program 49 Media and Outreach Program 53 III. Appendix 57 Appendix 1: Paid Media Plan 58 Appendix 2: Equipment—Preapproved and Not Allowable 86 Appendix 3: Safety: Partners, Committees, and Organizations 87 Appendix 4: Targeting used for Alcohol, Speed, and Occupant Protection Enforcement Grants 88 Appendix 5: Highway Safety Program Cost Summary (HS217) 91 Appendix 6: Detailed Budget 92 Appendix 7: Bureau of Transportation Safety Organizational Chart 96 Appendix 8 and 9A-G: State Certifications and Assurances 97 See Supplemental Appendix for other Appendices STATE OF WISCONSIN FFY 2017 HIGHWAY SAFETY PLAN FFY 2017 HIGHWAY WISCONSIN OF STATE STATE OF WISCONSIN FFY 2017 HIGHWAY SAFETY PLAN HIGHWAY SAFETY PLAN SECTION I STATE OF WISCONSIN FFY 2017 1 MISSION STATEMENT (NHTSA), state funds, and other resources. Funds are primarily used to change system users' behaviors by Our mission is simple: zero fatalities on Wisconsin’s enforcing traffic laws, increasing drivers' perception of roadways. -

Kindergarten, Here I

Welcome! Reading to your child is one of the most important ways to help your child succeed in school. The Approaches to Learning through Play Kindergarten, Here I Am! Activity Guide introduces you to authors and illustrators who have written many books Creative Thinking and Expression that are fun and interesting for kindergarteners. Each ˜ Health, Wellness and Physical Development month you’ll learn about a children’s author or illustrator; each week you’ll learn about one of that author’s books. Language and Literacy Development: You can find these books in your local library or your Reading, Writing, Speaking and Listening child’s teacher may have them available to borrow. If ▲ Mathematics Thinking and Expression you don’t already have one, you may want to get a free library card for yourself and your child. After you Partnerships for Learning: complete a registration card and show proof of address, Families, Learning Environments and Commuities both of you can get a card that will open the doors to Science Thinking and Technology: new books and opportunities to read together. Exploration, Inquiry and Invention The activities that are described in Kindergarten, Here I Am! are fun to do even if you don’t have the books Social Emotional Development described on each page. Find other stories about the Social Studies Thinking: Connecting topics or just do the activities by themselves. Any way “Me” to My Community and the Larger World you play, they’re sure to help your child develop skills for future learning by sharing time together. The activities are linked to the Pennsylvania Early Learning Standards for Kindergarten.