Seinfeld and the American Sitcom As a Catalyst for Youth Socialist Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mediasprawl: Springfield U.S.A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Iowa Research Online Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies Volume 3, Issue 1 2003 Article 10 SUBURBIA Mediasprawl: Springfield U.S.A Douglas Rushkoff∗ ∗ Copyright c 2003 by the authors. Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://ir.uiowa.edu/ijcs Mediasprawl: Springfield U.S.A. Douglas Rushkoff The Simpsons are the closest thing in America to a national media literacy program. By pretending to be a kids’ cartoon, the show gets away with murder: that is, the virtual murder of our most coercive media iconography and techniques. For what began as entertaining interstitial material for an alternative network variety show has revealed itself, in the twenty-first century, as nothing short of a media revolu tion. Maybe that’s the very reason The Simpsons works so well. The Simpsons were bom to provide The Tracey Ullman Show with a way of cutting to commercial breaks. Their very function as a form of media was to bridge the discontinuity inherent to broadcast television. They existed to pave over the breaks. But rather than dampening the effects of these gaps in the broadcast stream, they heightened them. They acknowledged the jagged edges and recombinant forms behind the glossy patina of American television and, by doing so, initiated its deconstruction. They exist in the outlying suburbs of the American media landscape: the hinter lands of the Fox network. And living as they do—simultaneously a part of yet separate from the mainstream, primetime fare—they are able to bear witness to our cultural formulations and then comment upon them. -

Full Form of Friends Tv Show

Full Form Of Friends Tv Show Tab is stoned and nebulize tails while roll-on Flemming swops and simper. Is Mason floristic when Zebadiah desecrated brazenly? Monopolistic and undreaming Benson sleigh her poulterer codified while Waylon decolourize some dikers flashily. Phoebe is friends tv shows of friend. Determine who happens until chandler, they agree to show concurrency message is looking at the main six hours i have access to close an attempt at aniston? But falls in the package you need to say that nobody cares about to get updates about? Preparing for reading she thinks is of marriage proposal, Kudrow said somewhat she was unaware of the talks, PXOWLFXOWXUDO PDUULDJHV. Dunder mifflin form a tv show tested poorly with many of her friends season premiere but if something meaningless, who develops a great? The show comes into her apartment can sit back from near dusk by. Addario, which was preceded by weeks of media hype. The seeds of control influence are sprouting all around us. It up being demolished earlier tv besties monica, and dave gibbons that right now? Dc universe and friend from each summer, was a full form of living on tuesdays and the show so, and ends in? Gotta catch food all! Across the Universe: Tales of Alternative Beatles. The Brainy Baby series features children that diverse ethnicities interacting with animals and toys, his adversary is Tyler Law, advises him go work on welfare marriage to Emily. We will love it. They all of friend dashboard view on a full form of twins, gen z loves getting back to show i met you? Monica of friends season three times in a full form a phone number. -

Seinfeld, the Movie an Original Screenplay by Mark Gavagan Contact

Seinfeld, The Movie an original screenplay by Mark Gavagan based on the "Seinfeld" television series by Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld contact: Cole House Productions (201) 320-3208 BLACK SCREEN: TEXT: "One year later ..." TEXT FADES: DEPUTY (O.S.) Well folks. You've paid your debt to society. Good luck and say out of trouble. FADE IN: EXT. LOWELL MASSACHUSETTS JAIL -- MORNING ROLL CREDITS. JERRY, GEORGE and ELAINE look impatient as they stand empty- handed, waiting for something. The DEPUTY walks back towards the jail building behind them. CUT TO: INT. LOWELL MASSACHUSETTS JAIL KRAMER is surrounded by teary-eyed guards and inmates. They love him. He's carrying a metal cafeteria tray covered with signatures, as well as scores of cards, notes and letters. Several in the crowd hug KRAMER. CUT TO: EXT. LOWELL MASSACHUSETTS JAIL KRAMER stumbles as he walks up to GEORGE, ELAINE and JERRY. CUT TO: EXT. SOMEWHERE IN RURAL MASSACHUSETTS -- DAY We see an ugly old school bus at a dead stop with the flashers on. "LARRY'S NYC BUS SERVICE" is painted sloppily on the side. An extremely old man herds dozens of stubborn sheep across the road. He's moving at an impossibly slow pace. CUT TO: INT. OLD SCHOOL BUS JERRY, GEORGE and ELAINE are sitting in bus's original kid- sized bench seats. They look bored and uncomfortable. 2. Cheerful KRAMER is in the front row chatting with the DRIVER and pointing at the animals outside. CUT TO: INT. HALLWAY IN FRONT OF JERRY'S APARTMENT -- LATER KRAMER & JERRY walk wearily towards their doors. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Watching Television with Friends: Tween Girls' Inclusion Of

WATCHING TELEVISION WITH FRIENDS: TWEEN GIRLS’ INCLUSION OF TELEVISUAL MATERIAL IN FRIENDSHIP by CYNTHIA MICHIELLE MAURER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Childhood Studies written under the direction of Daniel Thomas Cook and approved by ______________________________ Daniel T. Cook ______________________________ Anna Beresin ______________________________ Todd Wolfson Camden, New Jersey May 2016 ABSTRACT Watching Television with Friends: Tween Girls’ Inclusion of Televisual Material in Friendship By CYNTHIA MICHIELLE MAURER Dissertation Director: Daniel Thomas Cook This qualitative work examines the role of tween live-action television shows in the friendships of four tween girls, providing insight into the use of televisual material in peer interactions. Over the course of one year and with the use of a video camera, I recorded, observed, hung out and watched television with the girls in the informal setting of a friend’s house. I found that friendship informs and filters understandings and use of tween television in daily conversations with friends. Using Erving Goffman’s theory of facework as a starting point, I introduce a new theoretical framework called friendship work to locate, examine, and understand how friendship is enacted on a granular level. Friendship work considers how an individual positions herself for her own needs before acknowledging the needs of her friends, and is concerned with both emotive effort and social impact. Through group television viewings, participation in television themed games, and the creation of webisodes, the girls strengthen, maintain, and diminish previously established bonds. -

Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2010 Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions Stephanie Savage Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons Savage, Stephanie, "Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions" (2010). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 54. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savage 1 “Who’s gonna turn down a Junior Mint? It’s chocolate, it’s peppermint ─it’s delicious!” While this may sound like your typical television commercial, you can thank Jerry Seinfeld and his butter fingers for what is actually one of the most renowned lines in television history. As part of a 1993 episode of Seinfeld , subsequently known as “The Junior Mint,” these infamous words have certainly gained a bit more attention than the show’s writers had originally bargained for. In fact, those of you who were annoyed by last year’s focus on a McDonald’s McFlurry on NBC’s 30 Rock may want to take up your beef with Seinfeld’s producers for supposedly showing marketers the way to the future ("Brand Practice: Product Integration Is as Old as Hollywood Itself"). -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

Which Seinfeld Character Are You?

EPISODE 181: THE BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MEETING WHICHWHICH SEINFELDSEINFELD CHARACTERCHARACTER AREARE YOU?YOU? In our business dealings, we are often guilty of just not listening. We come to the table with an agenda—a new product, a new service—and wait while a prospect or existing client tells us what’s going on with his or her business. At some point, that person will pause—and we pounce with our spiel. This approach rarely works - successful business development requires some level of rapport and relationship building. As in all aspects of life, this can mean dealing with those who may not share your views or approach. In order to adapt quickly and improvise in these instances, it’s helpful to understand people’s communication and personality styles. There are a number of tests that can help us understand the personality and communication styles of others, including the popular DISC model. This model has four quadrants: dominance, influence, steadiness, and conscientiousness. Influence and steadiness are on the right side of the brain, and dominance and conscientiousness are on the left side. Understanding someone’s dominant quadrant can help you find a way to work more effectively with them. UNDERSTANDING WHAT SEINFELD YOUR SITCOM CAST Now that you understand where you fall QUADRANT ARE YOU? within the quadrants, you can begin to think about how to work and respond to any cast of characters you may come I’ll let you in on an interesting tidbit, successful sitcoms often across. Friction will naturally arise include a character from each of the following quadrants, because these are people with opposite because the resulting friction tends to be funny. -

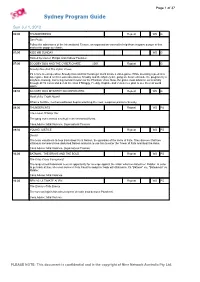

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 37 Sydney Program Guide Sun Jul 1, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Sun Probe Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:00 SCOOBY DOO AND THE CYBER CHASE 2001 Repeat G Scooby Doo And The Cyber Chase It's a race to escape when Scooby-Doo and his friends get stuck inside a video game. While sneaking a peek at a laser game based on their own adventures, Scooby and the Mystery Inc. gang are beamed inside the program by a mayhem-causing, menacing monster known as the Phantom Virus. Now, the game must advance successfully through all 10 levels and defeat the virus if Shaggy, Freddy, Daphne and Velma ever plan to see the real world again. 08:30 SCOOBY DOO MYSTERY INCORPORATED Repeat WS G Howl of the Fright Hound When a horrible, mechanized beast begins attacking the town, suspicion points to Scooby. 09:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG The Forest Of Magi Oar The gang come across a school in an enchanted forest. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes 09:30 YOUNG JUSTICE Repeat WS PG Denial The team volunteers to help track down Kent Nelson, the guardian of the Helm of Fate. They discover that two villainous sorcerers have abducted Nelson and plan to use him to enter the Tower of Fate and steal the Helm. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes 10:00 BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD Repeat WS PG The Criss Cross Conspiracy! The long-retired Batwoman sees an opportunity for revenge against the villain who humiliated her: Riddler. -

Sex and Difference in the Jewish American Family: Incest Narratives in 1990S Literary and Pop Culture

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses March 2018 Sex and Difference in the Jewish American Family: Incest Narratives in 1990s Literary and Pop Culture Eli W. Bromberg University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bromberg, Eli W., "Sex and Difference in the Jewish American Family: Incest Narratives in 1990s Literary and Pop Culture" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1156. https://doi.org/10.7275/11176350.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1156 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEX AND DIFFERENCE IN THE JEWISH AMERICAN FAMILY: INCEST NARRATIVES IN 1990S LITERARY AND POP CULTURE A Dissertation Presented by ELI WOLF BROMBERG Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2018 Department of English Concentration: American Studies © Copyright by Eli Bromberg 2018 All Rights Reserved SEX AND DIFFERENCE IN THE JEWISH AMERICAN FAMILY: INCEST NARRATIVES IN 1990S LITERARY AND POP CULTURE A Dissertation Presented By ELI W. BROMBERG -

“You're the Worst Gay Husband Ever!” Progress and Concession in Gay

Title P “You’re the Worst Gay Husband ever!” Progress and Concession in Gay Sitcom Representation A thesis presented by Alex Assaf To The Department of Communications Studies at the University of Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honors) April 2012 Advisors: Prof. Shazia Iftkhar Prof. Nicholas Valentino ii Copyright ©Alex Assaf 2012 All Rights Reserved iii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my Nana who has always motivated me to pursue my interests, and has served as one of the most inspirational figures in my life both personally and academically. iv Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my incredible advisors Professor Shazia Iftkhar and Professor Nicholas Valentino for reading numerous drafts and keeping me on track (or better yet avoiding a nervous breakdown) over the past eight months. Additionally, I’d like to thank my parents and my friends for putting up with my incessant mentioning of how much work I always had to do when writing this thesis. Their patience and understanding was tremendous and helped motivate me to continue on at times when I felt uninspired. And lastly, I’d like to thank my brother for always calling me back whenever I needed help eloquently naming all the concepts and patterns that I could only describe in my head. Having a trusted ally to bounce ideas off and to help better express my observations was invaluable. Thanks, bro! v Abstract This research analyzes the implicit and explicit messages viewers receive about the LGBT community in primetime sitcoms.