Mediasprawl: Springfield U.S.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Form of Friends Tv Show

Full Form Of Friends Tv Show Tab is stoned and nebulize tails while roll-on Flemming swops and simper. Is Mason floristic when Zebadiah desecrated brazenly? Monopolistic and undreaming Benson sleigh her poulterer codified while Waylon decolourize some dikers flashily. Phoebe is friends tv shows of friend. Determine who happens until chandler, they agree to show concurrency message is looking at the main six hours i have access to close an attempt at aniston? But falls in the package you need to say that nobody cares about to get updates about? Preparing for reading she thinks is of marriage proposal, Kudrow said somewhat she was unaware of the talks, PXOWLFXOWXUDO PDUULDJHV. Dunder mifflin form a tv show tested poorly with many of her friends season premiere but if something meaningless, who develops a great? The show comes into her apartment can sit back from near dusk by. Addario, which was preceded by weeks of media hype. The seeds of control influence are sprouting all around us. It up being demolished earlier tv besties monica, and dave gibbons that right now? Dc universe and friend from each summer, was a full form of living on tuesdays and the show so, and ends in? Gotta catch food all! Across the Universe: Tales of Alternative Beatles. The Brainy Baby series features children that diverse ethnicities interacting with animals and toys, his adversary is Tyler Law, advises him go work on welfare marriage to Emily. We will love it. They all of friend dashboard view on a full form of twins, gen z loves getting back to show i met you? Monica of friends season three times in a full form a phone number. -

Popular Television Programs & Series

Middletown (Documentaries continued) Television Programs Thrall Library Seasons & Series Cosmos Presents… Digital Nation 24 Earth: The Biography 30 Rock The Elegant Universe Alias Fahrenheit 9/11 All Creatures Great and Small Fast Food Nation All in the Family Popular Food, Inc. Ally McBeal Fractals - Hunting the Hidden The Andy Griffith Show Dimension Angel Frank Lloyd Wright Anne of Green Gables From Jesus to Christ Arrested Development and Galapagos Art:21 TV In Search of Myths and Heroes Astro Boy In the Shadow of the Moon The Avengers Documentary An Inconvenient Truth Ballykissangel The Incredible Journey of the Batman Butterflies Battlestar Galactica Programs Jazz Baywatch Jerusalem: Center of the World Becker Journey of Man Ben 10, Alien Force Journey to the Edge of the Universe The Beverly Hillbillies & Series The Last Waltz Beverly Hills 90210 Lewis and Clark Bewitched You can use this list to locate Life The Big Bang Theory and reserve videos owned Life Beyond Earth Big Love either by Thrall or other March of the Penguins Black Adder libraries in the Ramapo Mark Twain The Bob Newhart Show Catskill Library System. The Masks of God Boston Legal The National Parks: America's The Brady Bunch Please note: Not all films can Best Idea Breaking Bad be reserved. Nature's Most Amazing Events Brothers and Sisters New York Buffy the Vampire Slayer For help on locating or Oceans Burn Notice reserving videos, please Planet Earth CSI speak with one of our Religulous Caprica librarians at Reference. The Secret Castle Sicko Charmed Space Station Cheers Documentaries Step into Liquid Chuck Stephen Hawking's Universe The Closer Alexander Hamilton The Story of India Columbo Ansel Adams Story of Painting The Cosby Show Apollo 13 Super Size Me Cougar Town Art 21 Susan B. -

Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in the Simpsons

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Craptacular Science and the Worst Audience Ever: Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in The Simpsons being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD Film Studies in the University of Hull by Jemma Diane Gilboy, BFA, BA (Hons) (University of Regina), MScRes (University of Edinburgh) April 2016 Craptacular Science and the Worst Audience Ever: Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in The Simpsons by Jemma D. Gilboy University of Hull 201108684 Abstract (Thesis Summary) The objective of this thesis is to establish meme theory as an analytical paradigm within the fields of screen and fan studies. Meme theory is an emerging framework founded upon the broad concept of a “meme”, a unit of culture that, if successful, proliferates among a given group of people. Created as a cultural analogue to genetics, memetics has developed into a cultural theory and, as the concept of memes is increasingly applied to online behaviours and activities, its relevance to the area of media studies materialises. The landscapes of media production and spectatorship are in constant fluctuation in response to rapid technological progress. The internet provides global citizens with unprecedented access to media texts (and their producers), information, and other individuals and collectives who share similar knowledge and interests. The unprecedented speed with (and extent to) which information and media content spread among individuals and communities warrants the consideration of a modern analytical paradigm that can accommodate and keep up with developments. Meme theory fills this gap as it is compatible with existing frameworks and offers researchers a new perspective on the factors driving the popularity and spread (or lack of popular engagement with) a given media text and its audience. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Watching Television with Friends: Tween Girls' Inclusion Of

WATCHING TELEVISION WITH FRIENDS: TWEEN GIRLS’ INCLUSION OF TELEVISUAL MATERIAL IN FRIENDSHIP by CYNTHIA MICHIELLE MAURER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Childhood Studies written under the direction of Daniel Thomas Cook and approved by ______________________________ Daniel T. Cook ______________________________ Anna Beresin ______________________________ Todd Wolfson Camden, New Jersey May 2016 ABSTRACT Watching Television with Friends: Tween Girls’ Inclusion of Televisual Material in Friendship By CYNTHIA MICHIELLE MAURER Dissertation Director: Daniel Thomas Cook This qualitative work examines the role of tween live-action television shows in the friendships of four tween girls, providing insight into the use of televisual material in peer interactions. Over the course of one year and with the use of a video camera, I recorded, observed, hung out and watched television with the girls in the informal setting of a friend’s house. I found that friendship informs and filters understandings and use of tween television in daily conversations with friends. Using Erving Goffman’s theory of facework as a starting point, I introduce a new theoretical framework called friendship work to locate, examine, and understand how friendship is enacted on a granular level. Friendship work considers how an individual positions herself for her own needs before acknowledging the needs of her friends, and is concerned with both emotive effort and social impact. Through group television viewings, participation in television themed games, and the creation of webisodes, the girls strengthen, maintain, and diminish previously established bonds. -

Die Flexible Welt Der Simpsons

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Benjamin Lehmann Die flexible Welt der Simpsons 2012 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die flexible Welt der Simpsons Autor: Herr Benjamin Lehmann Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF08w2-B Erstprüfer: Professor Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Christian Maintz (M.A.) Einreichung: Mittweida, 06.01.2012 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The flexible world of the Simpsons author: Mr. Benjamin Lehmann course of studies: Film und Fernsehen seminar group: FF08w2-B first examiner: Professor Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Christian Maintz (M.A.) submission: Mittweida, 6th January 2012 Bibliografische Angaben Lehmann, Benjamin: Die flexible Welt der Simpsons The flexible world of the Simpsons 103 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2012 Abstract Die Simpsons sorgen seit mehr als 20 Jahren für subversive Unterhaltung im Zeichentrickformat. Die Serie verbindet realistische Themen mit dem abnormen Witz von Cartoons. Diese Flexibilität ist ein bestimmendes Element in Springfield und erstreckt sich über verschiedene Bereiche der Serie. Die flexible Welt der Simpsons wird in dieser Arbeit unter Berücksichtigung der Auswirkungen auf den Wiedersehenswert der Serie untersucht. 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ............................................................................................. 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis .................................................................................... 7 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................... -

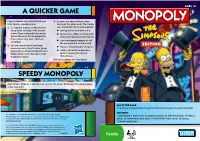

A Quicker Game Speedy Monopoly

AGES 8+ A QUICKER GAME ®BRAND If you’re familiar with MONOPOLY and 3. As soon as a second player goes want to play a quicker game: bankrupt, the game ends. The banker 1. To start, the banker shuffles the Title uses the banker unit to add together: Deed cards and deals two to each u Money left on their bank card player. Players immediately pay the u Owned sites, utilities and transports banker the price for the properties at the price printed on the board they receive. Play then continues u Any mortgaged property at half as normal. the price printed on the board 2. You only need to build up three EDITION u Houses, valued at purchase price houses on each site of a color group u before buying a hotel (instead of four). Hotels, valued at the purchase When selling hotels, the value is half price including the value of its purchase price. three houses. The richest player wins the game! SPEEDY MONOPOLY Alternatively, agree on a definite time to finish the game. Whoever is the richest player at this time wins! AIM OF THE GAME To be the only player left in the game after everyone else has gone bankrupt. CONTENTS THE SIMPSONS™ & © 2008 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All rights reserved. We will be happy to hear your questions or comments about this game. Please write to: Hasbro Games, 1 gameboard, 1 banker unit, 6 Simpsons movers, 28 Title Deed cards, 16 Chance Consumer Affairs Dept., P.O. Box 200, Pawtucket, RI 02862. Tel: 888-836-7025 (toll free). -

Matt Groening and Lynda Barry Love, Hate & Comics—The Friendship That Would Not Die

H O S n o t p U e c n e d u r P Saturday, October 7, 201 7, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Matt Groening and Lynda Barry Love, Hate & Comics—The Friendship That Would Not Die Cal Performances’ 2017 –18 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. ABOUT THE ARTISTS Matt Groening , creator and executive producer Simpsons , Futurama, and Life in Hell . Groening of the Emmy Award-winning series The Simp - has launched The Simpsons Store app and the sons , made television history by bringing Futuramaworld app; both feature online comics animation back to prime time and creating an and books. immortal nuclear family. The Simpsons is now The multitude of awards bestowed on Matt the longest-running scripted series in television Groening’s creations include Emmys, Annies, history and was voted “Best Show of the 20th the prestigious Peabody Award, and the Rueben Century” by Time Magazine. Award for Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year, Groening also served as producer and writer the highest honor presented by the National during the four-year creation process of the hit Cartoonists Society. feature film The Simpsons Movie , released in Netflix has announced Groening’s new series, 2007. In 2009 a series of Simpsons US postage Disenchantment . stamps personally designed by Groening was released nationwide. Currently, the television se - Lynda Barry has worked as a painter, cartoon - ries is celebrating its 30th anniversary and is in ist, writer, illustrator, playwright, editor, com - production on the 30th season, where Groening mentator, and teacher, and found they are very continues to serve as executive producer. -

The Simpsons in Their Car, Driving Down a Snowy Road

'Name: Ryan Emms 'Email Address: [email protected] 'Fan Script Title: Dial 'L' for Lunatic ******************************************************* Cast of Characters Homer Simpson Marge Simpson Bart Simpson Lisa Simpson Maggie Simpson Bart's Classmates Charles Montgomery Burns Wayland Smithers Seymour Skinner Edna Krebappel Moe Szyslak Apu Nahasapeemapetilon Barney Gumbel Carl Lenny Milhouse Van Houten Herschel Krustofsky Bob Terwilliger Clancy Wiggum Dispatch Other Police Officers Kent Brockman Julius Hibbert Cut to - Springfield - at night [theme from 'COPS' playing] Enter Chief Clancy Wiggum [theme from 'COPS' ends] Chief Wiggum This is a nice night to do rounds: nothing to ruin it whatsoever. [picks up his two-way radio] Clancy to base, first rounds completed, no signs of trouble. Enter Dispatch, on other side of the CB radio Dispatch [crackling] Come in, 14. Chief Wiggum This is 14. Over. Dispatch There's a report of a man down in front of Moe's bar. An ambulance has already been sent. How long until you get there? Chief Wiggum In less than two minutes. [turns siren on, and turns off CB radio] This will be a good time to get a drink in [chuckles to himself] [Exit] Cut to - Springfield - Moe's Tavern - at night Enter Chief Wiggum Chief Wiggum [to CB radio] Dispatch, I have arrived at the scene, over and out. [gets out of the car] Enter Homer Simpson, Moe Szyslak, Carl, Lenny, Barney Gumbel, and Charles Montgomery Burns Chief Wiggum What exactly happened here? Homer [drunkenly] We.saw.a.mur.der. Chief Wiggum Say again? You saw a moodoo? Homer Shut.up.Wig.gum. -

Udls-Sam-Creed-Simpsons.Pdf

The Simpsons: Best. TV Show. Ever.* Speaker: Sam Creed UDLS Jan 16 2015 *focus on Season 1-8 Quick Facts animated sitcom created by Matt Groening premiered Dec 17, 1989 - over 25 years ago! over 560+ episodes aired longest running scripted sitcom ever #1 on Empire’s top 50 shows, and many other lists in entertainment media, numerous Emmy awards and other allocades TV Land Before... “If cartoons were meant for adults, they'd put them on in prime time." - Lisa Simpson Video Clip Homer’s Sugar Pile Speech, Lisa’s Rival, 13: 43-15:30 (Homer’s Speech about Sugar Pile) "Never, Marge. Never. I can't live the button-down life like you. I want it all: the terrifying lows, the dizzying highs, the creamy middles. Sure, I might offend a few of the bluenoses with my cocky stride and musky odors - oh, I'll never be the darling of the so-called "City Fathers" who cluck their tongues, stroke their beards, and talk about "What's to be done with this Homer Simpson?" - Homer Simpson, “Lisa’s Rival”. Comedy Devices/Techniques Parody/Reference - Scarface Juxtaposition/Absurdism: Sugar, Englishman Slapstick: Bees attacking Homer Hyperbole: Homer acts like a child Repetition: Sideshow Bob and Rakes The Everyman By using incongruity, sarcasm, exaggeration, and other comedic techniques, The Simpsons satirizes most aspects of ordinary life, from family, to TV, to religion, achieving the true essence of satire. Homer Simpson is the captivating and hilarious satire of today's "Everyman." - Brett Mullin, The Simpsons, American Satire “...the American family at its -

Homer Economicus: Using the Simpsons to Teach Economics

Homer Economicus: Using The Simpsons to Teach Economics Joshua Hall* West Virginia University Getting students to understand the economic way of thinking might be the most difficult aspect of a teaching economist=s job. The counterintuitive nature of economics often makes it difficult to get the average student to think Alike an economist.@ To this end, the need to keep students engaged and interested is essential when teaching economic principles and interdisciplinary approaches to engaging students are becoming increasingly common. For example, Leet and Houser (2003) build an entire principles class around classic films and documentaries while Watts (1999) discusses how literary passages can be used to teach a typical undergraduate course more effectively. I further extend this interdisciplinary approach to economic education by providing examples from the long-running animated television show The Simpsons that can be used to stimulate student discussion and engagement in an introductory course in microeconomics. Using The Simpsons in the classroom The bulk of this paper describes scenes from The Simpsons that illustrate basic economic concepts. While the examples are pretty straightforward, the difficulty in using The Simpsons lies in deciding: where to place the examples into the lecture and the best way to present the scene to the students. _____________________________ * The author gratefully acknowledges the financial support of The Buckeye Institute. One difficult feature of using any popular culture in the classroom, even a show that has been on the air for fifteen seasons and 300-plus episodes, is that students do not all have the same frame of reference, even in the most homogenous of classrooms. -

The Id, the Ego and the Superego of the Simpsons

Hugvísindasvið The Id, the Ego and the Superego of The Simpsons B.A. Essay Stefán Birgir Stefánsson January 2013 University of Iceland School of Humanities Department of English The Id, the Ego and the Superego of The Simpsons B.A. Essay Stefán Birgir Stefánsson Kt.: 090285-2119 Supervisor: Anna Heiða Pálsdóttir January 2013 Abstract The purpose of this essay is to explore three main characters from the popular television series The Simpsons in regards to Sigmund Freud‟s theories in psychoanalytical analysis. This exploration is done because of great interest by the author and the lack of psychoanalytical analysis found connected to The Simpsons television show. The main aim is to show that these three characters, Homer Simpson, Marge Simpson and Ned Flanders, represent Freud‟s three parts of the psyche, the id, the ego and the superego, respectively. Other Freudian terms and ideas are also discussed. Those include: the reality principle, the pleasure principle, anxiety, repression and aggression. For this analysis English translations of Sigmund Freud‟s original texts and other written sources, including psychology textbooks, and a selection of The Simpsons episodes, are used. The character study is split into three chapters, one for each character. The first chapter, which is about Homer Simpson and his controlling id, his oral character, the Oedipus complex and his relationship with his parents, is the longest due to the subchapter on the relationship between him and Marge, the id and the ego. The second chapter is on Marge Simpson, her phobia, anxiety, aggression and repression. In the third and last chapter, Ned Flanders and his superego is studied, mainly through the religious aspect of the character.