Silent Magic: Trick Films and Special Effects, 1895-1912

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Study Notes

Hugo Directed by: Martin Scorsese Certificate: U Country: USA Running time: 126 mins Year: 2011 Suitable for: primary literacy; history (of cinema); art and design; modern foreign languages (French) www.filmeducation.org 1 ©Film Education 2012. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external sites SYNOPSIS Based on a graphic novel by Brian Selznick, Hugo tells the story of a wily and resourceful orphan boy who lives with his drunken uncle in a 1930s Paris train station. When his uncle goes missing one day, he learns how to wind the huge station clocks in his place and carries on living secretly in the station’s walls. He steals small mechanical parts from a shop owner in the station in his quest to unlock an automaton (a mechanical man) left to him by his father. When the shop owner, George Méliès, catches him stealing, their lives become intertwined in a way that will transform them and all those around them. www.hugomovie.com www.theinventionofhugocabret.com TeacHerS’ NOTeS These study notes provide teachers with ideas and activity sheets for use prior to and after seeing the film Hugo. They include: ■ background information about the film ■ a cross-curricular mind-map ■ classroom activity ideas – before and after seeing the film ■ image-analysis worksheets (for use to develop literacy skills) These activity ideas can be adapted to suit the timescale available – teachers could use aspects for a day’s focus on the film, or they could extend the focus and deliver the activities over one or two weeks. www.filmeducation.org 2 ©Film Education 2012. -

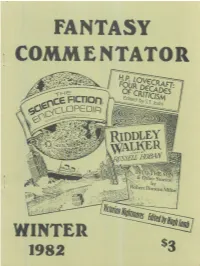

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A. Langley Searles Lee Becker, T. G. Cockcroft, 7 East 235th St. Sam Moskowitz, Lincoln Bronx, N. Y. 10470 Van Rose, George T. Wetzel Vol. IV, No. 4 -- oOo--- Winter 1982 Articles Needle in a Haystack Joseph Wrzos 195 Voyagers Through Infinity - II Sam Moskowitz 207 Lucky Me Stephen Fabian 218 Edward Lucas White - III George T. Wetzel 229 'Plus Ultra' - III A. Langley Searles 240 Nicholls: Comments and Errata T. G. Cockcroft and 246 Graham Stone Verse It's the Same Everywhere! Lee Becker 205 (illustrated by Melissa Snowind) Ten Sonnets Stanton A. Coblentz 214 Standing in the Shadows B. Leilah Wendell 228 Alien Lee Becker 239 Driftwood B. Leilah Wendell 252 Regular Features Book Reviews: Dahl's "My Uncle Oswald” Joseph Wrzos 221 Joshi's "H. P. L. : 4 Decades of Criticism" Lincoln Van Rose 223 Wetzel's "Lovecraft Collectors Library" A. Langley Searles 227 Moskowitz's "S F in Old San Francisco" A. Langley Searles 242 Nicholls' "Science Fiction Encyclopedia" Edward Wood 245 Hoban's "Riddley Walker" A. Langley Searles 250 A Few Thorns Lincoln Van Rose 200 Tips on Tales staff 253 Open House Our Readers 255 Indexes to volume IV 266 This is the thirty-second number of Fantasy Commentator^ a non-profit periodical of limited circulation devoted to articles, book reviews and verse in the area of sci ence - fiction and fantasy, published annually. Subscription rate: $3 a copy, three issues for $8. All opinions expressed herein are the contributors' own, and do not necessarily reflect those of the editor or the staff. -

The Cameraman's Revenge

Klassiki Cinema on the Hop Tuesday 14 April 2020 The Cameraman’s Revenge (1912) #Klassiki2 by Ladislas Starevich Ladislas Starevich is, to be frank, a name that everybody wonder whether this great heritage was fostered somewhat should know. A true pioneer, he is an early Russian stop by Starevich’s position as originator and homegrown genius. motion animator and his contributions to cinema still resonate today. The list of filmmakers he has influenced Animation lends itself to anthropomorphising animals, but includes luminaries such as Wes Anderson, the Brothers Quay Starevich was one of the first to tap into this power. He and Tim Burton. Charles Henri Ford, the American poet and stumbled accidentally on animation. As the Director of the filmmaker, stated that, “Starevich is one of those cinemagicians Natural History Museum in Kaunas, Lithuania, he wanted to whose name deserves to stand in film history alongside those of document the rituals of stag beetles. Upon finding that the Méliès, Emil Cohl and Disney.’” Not only was he technically nocturnal creatures went to sleep almost as soon as light innovative, Starevich had an artistic vision and keen turned on them, he decided to use the carcasses of dead emotional sensibility that makes his films utterly compelling. insects to produce educational films. However, he soon His stylistic imprint can be seen on many modern day plumbed the potential of this medium. The Cameraman’s classics. Recent contemporary animated films with entire Revenge is one of Starevich’s earliest films, and the direct sequences that reference his films include Wes Anderson’s result of this revelation. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

The Old and the New Magic

E^2 CORNELL UNIVERSITY gilBRARY . GIFT OF THE AUTHOR Digitized by Microsoft® T^^irt m4:£±z^ mM^^ 315J2A. j^^/; ii'./jvf:( -UPHF ^§?i=£=^ PB1NTEDINU.S.A. Library Cornell University GV1547 .E92 Old and the new maj 743 3 1924 029 935 olin Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® ROBERT-KCUIUT Digitized by Microsoft® THE OLDUI^DIMEJ^ MAGIC BY HENRY RIDGELY EVANS INTRODUCTION E1^ k -io^s-ji, Copyright 1906 BY The Open Court Publishing Co. Chicago -J' Digitized by Microsoft® \\\ ' SKETCH OF HENRY RIDGELY EVAXS. "Elenry Ridgely Evans, journalist, author and librarian, was born in Baltimore, ^Md., Xovember 7, 1861. He is the son 01 Henry Cotheal and Alary (Garrettson) Evans. Through his mother he is descended from the old colonial families of Ridgely, Dorsey, AA'orthington and Greenberry, which played such a prominent part in the annals of early Maryland. \h. Evans was educated at the preparatory department of Georgetown ( D. C.) College and at Columbian College, Washington, D. C He studied law at the University of Maryland, and began its practice in Baltimore City ; but abandoned the legal profession for the more congenial a\'ocation <jf journalism. He served for a number of }ears as special reporter and dramatic critic on the 'Baltimore N'ews,' and subsequently became connected with the U. -

Ladislaw Starewicz: Ein filmo-Bibliographisches Verzeichnis 2012

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Katja Bruns Ladislaw Starewicz: Ein filmo-bibliographisches Verzeichnis 2012 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12767 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Bruns, Katja: Ladislaw Starewicz: Ein filmo-bibliographisches Verzeichnis. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, Institut für Germanistik 2012 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 135). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12767. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0135_12.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft / Hamburg: Berichte und Papiere 135, 2012: Ladislaw Starewicz. Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Katja Bruns. ISSN 1613-7477. URL: http://www.rrz.uni-hamburg.de/Medien/berichte/arbeiten/0135_12.pdf Letzte redaktionelle Änderung: 9.3.2012. Ladislaw Starewicz: Ein filmo-bibliographisches Verzeichnis Zusammengestellt von Katja Bruns Inhalt: Starewicz war Kind polnischer Eltern, die aus Litau- 1. Biographie en stammten. Seine Mutter starb 1886. Er wuchs bei 2. Filmographie seinen Großeltern -

Proquest Dissertations

Early Cinema and the Supernatural by Murray Leeder B.A. (Honours) English, University of Calgary, M.A. Film Studies, Carleton University A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations © Murray Leeder September 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-83208-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-83208-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Georges Méliès: Impossible Voyager

Georges Méliès: Impossible Voyager Special Effects Epics, 1902 – 1912 Thursday, May 15, 2008 Northwest Film Forum, Seattle, WA Co-presented by The Sprocket Society and the Northwest Film Forum Curated and program notes prepared by Spencer Sundell. Special music presentations by Climax Golden Twins and Scott Colburn. Poster design by Brian Alter. Projection: Matthew Cunningham. Mr. Sundell’s valet: Mike Whybark. Narration for The Impossible Voyage translated by David Shepard. Used with permission. (Minor edits were made for this performance.) It can be heard with a fully restored version of the film on the Georges Méliès: First Wizard of Cinema (1896-1913) DVD box set (Flicker Alley, 2008). This evening’s program is dedicated to John and Carolyn Rader. The Sprocket Society …seeks to cultivate the love of the mechanical cinema, its arts and sciences, and to encourage film preservation by bringing film and its history to the public through screenings, educational activities, and our own archival efforts. www.sprocketsociety.org [email protected] The Northwest Film Forum Executive Director: Michael Seirwrath Managing Director: Susie Purves Programming Director: Adam Sekuler Associate Program Director: Peter Lucas Technical Director: Nora Weideman Assistant Technical Director: Matthew Cunningham Communications Director: Ryan Davis www.nwfilmforum.org nwfilmforum.wordpress.com THE STAR FILMS STUDIO, MONTREUIL, FRANCE The exterior of the glass-house studio Méliès built in his garden at Montreuil, France — the first movie The interior of the same studio. Méliès can be seen studio of its kind in the world. The short extension working at left (with the long stick). As you can with the sloping roof visible at far right is where the see, the studio was actually quite small. -

A Trip to the Moon As Féerie

7 FRANK KESSLER A Trip to the Moon as Féerie SHORT STORY BY JULES VERNE, first published in 1889 and describ- ing a day in the life of an American journalist in the year 2889, Aopens with the intriguing remark that “in this twenty-ninth cen- tury people live right in the middle of a continuous féerie without even noticing it.”1 This observation linking technological and scientific prog- ress to the magical world of fairy tales quite probably did not surprise Verne’s French readers at the end of the nineteenth century when widely used expressions such as “la fée électricité” emphatically conjured up the image of wondrous magic to celebrate the marvels of the modern age. However, the choice of the term “féerie,” opens up yet another dimen- sion of Verne’s metaphor, namely the realm of the spectacular. A popu- lar stage genre throughout the nineteenth century, the féerie stood for a form of theatrical entertainment combining visual splendor, fantastic plots, amazing tricks, colorful ballets, and captivating music. All these wonders, on the other hand, were not the result of any kind of magic, but of stagecraft, set design, trick techniques, and a meticulously organized mise-en-scène. Verne’s metaphor, thus, complexly intertwines magic and technology, fairy tales and progress, fantasy and science. This, precisely, is the context within which I propose to look at Méliès’s 1902 film A Trip to the Moon2—as a féerie; that is, as a film drawing from a long-standing stage tradition that had also found its way into animated pictures where Copyright © 2011. -

Syllabus Is to Be Used As a Guideline Only

**Disclaimer** This syllabus is to be used as a guideline only. The information provided is a summary of topics to be covered in the class. Information contained in this document such as assignments, grading scales, due dates, office hours, required books and materials may be from a previous semester and are subject to change. Please refer to your instructor for the most recent version of the syllabus. Fall 2018 Instructor: Dr. Ana Hedberg Olenina E-Mail: [email protected] SLC 340 Office: LL 414-D Office Hrs.: Mon. 2:30-3:30 pm & by Approaches to International Cinema appointment Overview Materials This course offers a historical survey of major film movements around the TWO BOOKS to be purchased: world, from the silent era to this day. We will explore key cinematic works, situating them in their aesthetic, cultural, and political contexts, and tracing their -- Bordwell, David and Kristin impact on the global cinematic culture. The course is organized around weekly Thompson, Film History: An Introduction. case studies of pivotal moments in national film histories – French, German, THIRD EDITION (New York: McGraw Italian, Russian, American, Japanese, Indian, Chinese, Korean, Brazilian, Hill, 2009). ISBN: 9780073386133 Senegalese, and others. We will aim to understand how and why cinematic expression around the world developed the way it did. What practices informed the emergence of stylistic innovations? What factors shaped their distribution -- Greiger, Jeffrey and R. L. Rutsky, Film and reception in the global market over time? Finally, we will critically examine Analysis: A Norton Reader. SECOND the very notion of “national” cinema – a concept that often disguises the EDITION. -

Brief History of Special/Visual Effects in Film

Brief History of Special/Visual Effects in Film Early years, 1890s. • Birth of cinema -- 1895, Paris, Lumiere brothers. Cinematographe. • Earlier, 1890, W.K.L .Dickson, assistant to Edison, developed Kinetograph. • One of these films included the world’s first known special effect shot, The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, by Alfred Clarke, 1895. Georges Melies • Father of Special Effects • Son of boot-maker, purchased Theatre Robert-Houdin in Paris, produced stage illusions and such as Magic Lantern shows. • Witnessed one of first Lumiere shows, and within three months purchased a device for use with Edison’s Kinetoscope, and developed his own prototype camera. • Produced one-shot films, moving versions of earlier shows, accidentally discovering “stop-action” for himself. • Soon using stop-action, double exposure, fast and slow motion, dissolves, and perspective tricks. Georges Melies • Cinderella, 1899, stop-action turns pumpkin into stage coach and rags into a gown. • Indian Rubber Head, 1902, uses split- screen by masking areas of film and exposing again, “exploding” his own head. • A Trip to the Moon, 1902, based on Verne and Wells -- 21 minute epic, trompe l’oeil, perspective shifts, and other tricks to tell story of Victorian explorers visiting the moon. • Ten-year run as best-known filmmaker, but surpassed by others such as D.W. Griffith and bankrupted by WW I. Other Effects Pioneers, early 1900s. • Robert W. Paul -- copied Edison’s projector and built his own camera and projection system to sell in England. Produced films to sell systems, such as The Haunted Curiosity Shop (1901) and The ? Motorist (1906).