Athletics in Ancient Macedonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lara O'sullivan, Fighting with the Gods

The Ancient History Bulletin VOLUME TWENTY-EIGHT: 2014 NUMBERS 3-4 Edited by: Edward Anson ò David Hollander ò Timothy Howe Joseph Roisman ò John Vanderspoel ò Pat Wheatley ò Sabine Müller ISSN 0835-3638 ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Volume 28 (2014) Numbers 3-4 Edited by: Edward Anson, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Editorial correspondents Elizabeth Baynham, Hugh Bowden, Franca Landucci Gattinoni, Alexander Meeus, Kurt Raaflaub, P.J. Rhodes, Robert Rollinger, Victor Alonso Troncoso Contents of volume twenty-eight Numbers 3-4 82 Lara O’Sullivan, Fighting with the Gods: Divine Narratives and the Siege of Rhodes 99 Michael Champion, The Siege of Rhodes and the Ethics of War 112 Alexander K. Nefedkin, Once More on the Origin of Scythed Chariot 119 David Lunt, The Thrill of Victory and the Avoidance of Defeat: Alexander as a Sponsor of Athletic Contests NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS AND SUBSCRIBERS The Ancient History Bulletin was founded in 1987 by Waldemar Heckel, Brian Lavelle, and John Vanderspoel. The board of editorial correspondents consists of Elizabeth Baynham (University of Newcastle), Hugh Bowden (Kings College, London), Franca Landucci Gattinoni (Università Cattolica, Milan), Alexander Meeus (University of Leuven), Kurt Raaflaub (Brown University), P.J. Rhodes (Durham University), Robert Rollinger (Universität Innsbruck), Victor Alonso Troncoso (Universidade da Coruña) AHB is currently edited by: Timothy Howe (Senior Editor: [email protected]), Edward Anson, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel and Pat Wheatley. AHB promotes scholarly discussion in Ancient History and ancillary fields (such as epigraphy, papyrology, and numismatics) by publishing articles and notes on any aspect of the ancient world from the Near East to Late Antiquity. -

The Rise of the Games the Olympic Games Originated Long Ago In

The Rise of the Games The Olympic Games originated long ago in ancient Greece. Exactly when the Games were first held and what circumstances led to their creation is uncertain. We do know, however, that the Games were a direct outgrowth of the values and beliefs of Greek society. The Greeks idealized physical fitness and mental discipline, and they believed that excellence in those areas honored Zeus, the greatest of all their gods. One legend about the origin of the Olympic Games revolves around Zeus. It was said Zeus once fought his father, Kronos, for control of the world. Although we do not know just when the Games were first played, the earliest recorded Olympic competition occurred in 776 B.C. It had only one event, the one-stade (approximately 630-foot or 192-meter) race, which was won by a cook named Coroebus. This was the start of the first Olympiad, the four-year period by which the Greeks recorded their history. Generally, only freeborn men and boys could take part in the Olympic Games (servants and slaves were allowed to participate only in the horse races). Women were forbidden, on penalty of death, even to see the Games. In 396 B.C. , however, a woman from Rhodes successfully defied the death penalty. When her husband died, she continued the training of their son, a boxer. She attended the Games disguised as a man and was not recognized until she shouted with joy over her son's victory. Her life was spared because of the special circumstances and the fact that her father and brothers had been Olympians. -

Section Two ATHENS 2004 MISSION

2 IN the true spirit of the Games section two ATHENS 2004 MISSION he mission of Athens 2004 was broad in scope and precise in purpose. Combining ambition with clarity, the mission provided the Athens Organising Committee with succinct statements on an expansive foundation of goals. As a major theme of the 2004 Olympic Games had emphasised, all efforts of the Athens Organising Committee were made In the True Spirit of the Games. The Athens 2004 mission guided the management and execution of the 2004 Olympic Games. It gave purpose to the first global Olympic torch relay in history. It fostered a keen awareness of the impact of the 2004 Olympic Games on the athletes, the spectators, and the people around the world who would experience the return of the Games to the place of their ancient birth. The mission promised to uphold the Olympic ideals, to respect the culture and natural environment of Greece, and to showcase the nation’s past, present and future. It directed the Athens 2004 Olympic marketing agenda. And, finally, the mission encouraged an Olympic legacy that would benefit the Olympic Movement, the host country, and the world. 9 The Athens 2004 mission promised overall that the people of Greece would host unique Olympic Games on a human scale and inspire the world to celebrate the Olympic values. With breadth and focus, it promised to fulfill these nine goals: To organise technically excellent Olympic Games. To provide to the athletes, spectators, viewers and volunteers a unique Olympic experience, thus leaving behind a legacy for the Olympic Movement. -

Eustathius of Antioch in Modern Research

VOX PATRUM 33 (2013) t. 59 Sophie CARTWRIGHT* EUSTATHIUS OF ANTIOCH IN MODERN RESEARCH Eustathius of Beroea/Antioch remains an elusive figure, though there is a growing recognition of his importance to the history of Christian theology, and particularly the early part of the so-called ‘Arian’ controversies. The re- cent publication of a fresh edition of his writings, including a newly-attributed epitome entitled Contra Ariomanitas et de anima, demands fresh considera- tion of Eustathius1. However, the previous scholarship on Eustathius is too little known for such an enterprise to take place. This article has two related tasks: firstly, to provide a comprehensive survey of the treatment of Eustathius in modern scholarship2; secondly, to assess the current state of research on Eustathius. With the exception of Eustathian exegesis, the work on Eustathi- us’s theology between the early twentieth century and the publication of the new epitome has been extremely limited. The scholarship that has followed this publication has yet to situate its observations within more recent histo- riographical developments in patristic theology and philosophy, but points to- wards several contours that must be fundamental to this endeavour. Firstly, Eustathius’s relationship to Origen must be closely considered in connection with his long-noted dependence on Irenaeus and other theologians from Asia Minor. Secondly, Aristotle, or ‘Aristotelianism’, suggests itself as an impor- tant resource for Eustathius – this resource must now be understood in light of recent discussions on the role of Aristotle’s thought, and its relation to Plato- nism, in antiquity. This can, in turn, help to elucidate the history of Irenaeus’s legacy, Origenism, and readings of Aristotle in the fourth century. -

Roman Woman, Culture, and Law by Heather Faith Wright Senior Seminar

Roman Woman, Culture, and Law By Heather Faith Wright Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor John L. Rector Western Oregon University June 5, 2010 Readers Professor Benedict Lowe Professor Laurie Carlson Copyright @ Heather Wright, 2010 2 The topic of my senior thesis is Women of the Baths. Women were an important part of the activities and culture that took place within the baths. Throughout Roman history bathing was important to the Romans. By the age of Augustus visiting the baths had become one of the three main activities in a Roman citizen’s daily life. The baths were built following the current trends in architecture and were very much a part of the culture of their day. The architecture, patrons, and prostitutes of the Roman baths greatly influenced the culture of this institution. The public baths of both the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire were important social environment to hear or read poetry and meet lovers. Patrons were expected to wear special bathing costumes, because under various emperors it was illegal to bathe nude. It was also very important to maintain the baths; they were, at the top of the Roman government's list of social responsibilities. The baths used the current trends in architecture, and were very much a part of the culture of the day. Culture within the Roman baths, mainly the Imperial and Republican baths was essential to Roman society. The baths were complex arenas to discuss politics, have rendezvous with prostitutes and socialize with friends. Aqueducts are an example of the level of specialization which the Romans had reached in the glory days of the Republic. -

Greetings and Thanksgiving the Salutation

Thessalonians 1 & 2 1 Thessalonian 1: Greetings and Thanksgiving The Salutation The salutation names three authors of the letter, Paul, Silvanus, also known by his nickname Silas, and Timothy. Both of Paul’s fellow workers played important roles in the development of his missionary activity. According to Acts 15:22, Silas was part of the delegation sent to Antioch to announce the results of the “apostolic council” in Jerusalem. Paul chose him as a companion in his missionary activity in Syria and Cilicia, his “first missionary journey” (Acts 15:40). It was during that journey, in Derbe and Lystra, where Paul encountered Timothy, son of a Jewish mother and Greek father (Acts 16:1), whom he recruited to his missionary team. Silas continued with Paul and was with him in prison in Philippi (Acts 16:19–40), and he was with Paul when the apostle initially worked in Thessalonica (Acts 17:4-9) and Beroea (Acts 17:10). Timothy apparently was part of the team as well, since he remained with Silas in Beroea when Paul was sent off (Acts 17:14). Silas and Timothy reunited with Paul in Athens (Acts 18:5), which was probably the location from which Paul sent Timothy on the mission to Thessalonica, a mission to which he refers later in 1 Thess 3:2. If the account in Acts is correct, Silas accompanied Timothy on the trip; and the two rejoined Paul in Corinth (Acts 18:5), providing the occasion for writing the letter. The presence of Silas and Timothy with Paul in Corinth when he first preached there is confirmed by Paul’s reminiscence of the start of his mission there in 2 Corinthians 1:19. -

Background for the Bible Passage Session !: God in Culture

BACKGROUND FOR THE BIBLE PASSAGE SESSION !: GOD IN CULTURE Life Question: How can I use culture to express my who, no doubt, lifted him up mightily in prayer would be an faith? encouragement to him as he faced an entirely new experience Biblical Truth: We can start where people are in their in Athens. cultures to explain to them the message Certainly Paul had heard much about Athens previously, but of Christ. we can only imagine that he was ill-prepared for what he found Focal Passage: Acts 17:16-34 as he entered the city through one of its massive gates. The wall surrounding Athens had a circumference of 5 to 6 miles. Most likely Paul was awed by architecture that greeted him, with the Ben Feldman moved to Central City High School when he was grandeur of this center of Greek culture. If Paul had entered the a junior. His father, a prominent neurosurgeon, had joined the city through one of the northeast gates, he probably saw first medical faculty at Central City’s large teaching hospital. The the Hephaesteum, a beautiful Doric temple built between 449- family had moved from upstate New York to the deep South, 444 B.C. and dedicated to the god Hephaestus and the goddess and more specifically to the Bible Belt. Ben’s family came from Athena. Across from the Hephaesteum was the Stoa of Attalus, an entirely different culture in which “religion” was little more a two-storied, colonnaded building which was given to Athens than a traditional heritage. Ben was a brilliant student who around A.D. -

Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian

Epidamnus S tr Byzantium ym THRACE on R Amphipolis A . NI PROPONTIS O Eion ED Thasos Cyzicus C Stagira Aegospotami A Acanthus CHALCIDICE M Lampsacus Dascylium Potidaea Cynossema Scione Troy AEOLIS LY Corcyra SA ES Ambracia H Lesbos T AEGEAN MYSIA AE SEA Anactorium TO Mytilene Sollium L Euboea Arginusae Islands L ACAR- IA YD Delphi IA NANIA Delium Sardes PHOCISThebes Chios Naupactus Gulf Oropus Erythrae of Corinth IONIA Plataea Decelea Chios Notium E ACHAEA Megara L A Athens I R Samos Ephesus Zacynthus S C Corinth Piraeus ATTICA A Argos Icaria Olympia D Laureum I Epidaurus Miletus A Aegina Messene Delos MESSENIA LACONIA Halicarnassus Pylos Sparta Melos Cythera Rhodes 100 miles 160 km Crete Map 1 Greece. xvii W h i t 50 km e D r i n I R. D rin L P A E O L N IA Y Bylazora R . B S la t R r c R y k A . m D I A ) o r x i N a ius n I n n ( Epidamnus O r V e ar G C d ( a A r A n ) L o ig Lychnidus E r E P .E . R o (Ochrid) R rd a ic s u Heraclea u s r ) ( S o s D Lyncestis d u U e c ev i oll) Pella h l Antipatria C c l Edessa a Amphipolis S YN E TI L . G (Berat) E ( AR R DASS Celetrum Mieza Koritsa E O O R Beroea R.Ao R D Aegae (Vergina) us E A S E on Methone T m I A c Olynthus S lia Pydna a A Thermaic . -

14 Days at Your Local Passport Office

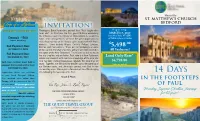

Hosted By: JOIN US YOUR ST. MATTHEW’S CHURCH for a BEDFORD Trip of a Lifetime INVITATION! Departing: IMPORTANT INFORMATION Theologian, Ernst Kasemann, posited that: “Paul taught what Jesus did.” St. Paul was the first great Christian missionary. MARCH 15, 2020 from New York, NY (JFK) $ His influence upon the history of Christendom is second to Deposit - 500 none. This coming March, we have the great opportunity to on Turkish Airlines or similar (upon booking) visit a large number of the historic sights associated with Paul’s ministry. Stops include Athens, Corinth, Philippi, Ephesus, $ .00 2nd Payment Due: Patmos, and many others. These are the birthplaces of some 5,498 OCTOBER 17, 2019 of the earliest Christian churches, and are well documented in All Inclusive! the pages of the New Testament. The trip will be led by me, as Full Payment Due: the trip chaplain, and my father, Paul, who is a New Testament Land Only Rate* DECEMBER 31, 2019 scholar and classicist with extensive knowledge of the area, and who has been visiting these places regularly for more than 40 $4,798.00 Each tour member must hold a years. Together, we will certainly deepen our understanding of passport that is valid until at least *Airfare not included our Christian roots, and, ultimately, connect with God in new OCTOBER 15, 2020. and exciting ways. Please join us for what will be a life-changing Application forms are available trip, following the footsteps of St. Paul. 14 Days at your local Passport Office. Grace & Peace, Any required visas other than IN THE FOOTSTEPS Turkey, will be processed for US citizens only. -

Vocabulary Worksheets Understanding and Using English Grammar, 4Th Edition Chapter 11: the Passive

Vocabulary Worksheets Understanding and Using English Grammar, 4th Edition Chapter 11: The Passive Worksheet 1. Reading: The Ancient Olympic Games Read the article about the ancient Olympic Games. Then review the glossary and complete the exercises that follow it. 1 According to legend, the ancient Olympic Games were founded by Heracles, a son of Zeus 2 (a Greek god). The first real Olympic Games for which we have written records were held in 3 776 BCE. These original Olympic Games were held on the plains of Olympia in Greece. 4 At the first Olympic Games, there was only one event: a sprint race, called the stadion race. 5 The word stadium is derived from this foot race. The race was 192 meters (210 yards) in 6 length and was won by a baker from a neighboring area. This first Olympic champion was 7 awarded the equivalent of today’s gold medal: a wreath of olive branches, which was placed 8 on his head. The olive tree of ancient Greece was not an ordinary tree; it was considered 9 sacred, so to be for an athlete to be crowned with an olive wreath was a holy honor. 10 Over the years, more races and more events were added, including wrestling, boxing, and 11 equestrian events (events with horses and people, such as chariot races and horse races). 12 In addition to the olive wreaths, winners received palm branches and woolen ribbons as 13 prizes. Winners of the Games were honored throughout Greece and were hailed as heroes in 14 their hometowns. -

From Symbol of Idealism to Money-Spinner

From Symbol of Idealism to Money-Spinner By Karl Lennartz 1 The traditional flag ceremonial at the Opening of the XXII Olympic Winter Games. The banner was carried among others by the ice hockey legend Vyacheslav Fetisov (far left), the six times Olympic speed skating champion Lidiya Skoblikova and by the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova. Photo: picture-alliance It was one of the most significant articles Coubertin To back up his theory, he looked at the list of countries ever wrote. It appeared in the August 1913 volume of the in Coubertin’s article: Sweden (for 1912), Greece (1896), Revue Olympique, a publication he had edited since France (1900), Great Britain (1908) and America (1904). 1901 and introduced his great symbol for the Olympic There followed Germany (1916), Belgium (1920), and Movement. “L’emblème et le drapeau de 1914”2 un- finally Italy, Hungary, Spain, Brazil, Australia, Japan and veiled the five coloured rings as the Olympic emblem China. 4 and flag. He had designed them for the 20th anniversary Young’s hypothesis provokes questions, in particular of the Olympic Movement, which was to be solemnly why Coubertin did not use the correct chronological celebrated in Paris in 1914 order, i.e. Athens, Paris, St. Louis, London and Stock- Coubertin interpreted the five rings as the five parts holm? How did Coubertin know, at the time of the of the world: “les cinq parties du monde“.3 By this he publication of his article, where the 1920 Games would could only have meant the continents of Africa, America, take place, for after all at the time of the Olympic Congress Asia, Australia and Europe, for in 1912 in Stockholm, the of 1914 there were still two applicants, Budapest and participation of two Japanese competitors meant that Antwerp, and the Hungarian capital was considered to all five were represented for the first time. -

Archaeology and the Book of Acts

Criswell Theological Review 5.1 (1990) 69-82. Copyright © 1990 by The Criswell College. Cited with permission. ARCHAEOLOGY AND THE BOOK OF ACTS JOHN MCRAY Wheaton College Graduate School, Wheaton, IL 60187 The winds of biblical scholarship have blown toward the Book of Acts from a largely theological direction for the past quarter of a century,1 providing a corrective to the pervasive concern with ques- tions of historicity fostered by the work of W. Ramsay almost a century ago.2 However, the winds are changing again, and interest is once more being kindled in questions relating to the trustworthiness of Acts. These changing winds are blowing from such unlikely places as the University of Tubingen itself, whose extremely critical views were held by Ram- say prior to his sojourn in Asia Minor. For example, M. Hengel, a NT scholar at Tubingen, "makes a bold departure from radical NT scholar- ship in supporting the historical integrity of the Acts of the Apostles. and demonstrates that Luke's account is historically reliable. ."3 Miti- gating cases against the hyperskepticism of scholars like J. Knox,4 and G. Leudemann,5 are now being made in various quarters bolstered by new discoveries in archaeological and inscriptional material.6 1 C. Talbert, ed., Perspectives on Luke-Acts (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1978); I. H. Marshall, Luke: Historian and Theologian (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1970); L. E. Keckand J. L. Martyn, Studies in Luke-Acts (Nashville: Abingdon, 1966). 2 W. Ramsay, St. Paul the Traveller and Roman Citizen (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1908); idem, The Cities of St.