Computer Support for Collaborative Learning (CSCL)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School of Library and Information Science Central University of Gujarat

School of Library and Information Science Central University of Gujarat Master of Library and Information Science COURSE AND CREDIT STRUCTURE Semester Course Course Title Credits Code 1 LIS-401 Knowledge Society 4 LIS-402 Knowledge Organization I: Classification (Theory & Practice) 3 LIS-403 Knowledge Processing I: Cataloguing (Theory & Practice) 3 LIS-404 Information Sources and Services 4 LIS-405 Information Communication Technology (Theory & Practice) 4 2 LIS-451 Management of Libraries and Information Centres 4 LIS-452 Information Storage and Retrieval 4 LIS-453 Knowledge Organization II: Classification (Theory & Practice) 3 LIS-454 Knowledge Processing II: Cataloguing (Theory & Practice) 3 LIS-455 Library Automation (Theory and Practice) 4 3 LIS-501 Research Methodology 4 LIS-502 Digital Libraries (Theory) 3 LIS-503 Web Technologies and Web-based Information Management 3 (Theory and Practice) LIS-541 Digital Libraries (Practice) 3 LIS-542 Library Internship in a Recognized Library/Information 5 Centre 4 LIS-551 Knowledge Management 4 LIS-552 Informetrics and Scientometrics 3 LIS-571* Social Science Information Systems 3 LIS-572* Community Information Systems LIS-573* Science Information Systems LIS-574* Agricultural Information Systems LIS-575* Health Information Systems LIS-591 Dissertation 8 Total credits 72 *Students are required to select any one course from LIS-571 to LIS-575 1 SEMESTER I Name of the Programme Master of Library and Information Science Course Title Knowledge Society Course Number LIS-401 Semester 1 Credits 4 Objectives of the Course: To introduce the basic concepts of knowledge and its formation To understand the influence of knowledge in the society To understand the process of communication Course Content: Evolution of Knowledge Society, Components, Dimensions, and Indicators of Knowledge Society. -

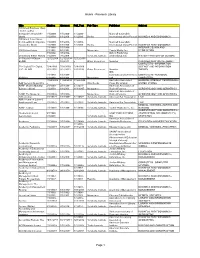

Research Library Page 1

Alumni - Research Library Title Citation Abstract Full_Text Pub Type Publisher Subject 100 Great Business Ideas : from Leading Companies Around the 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 100 Great Sales Ideas : from Leading Companies 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish Around the World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- INTERIOR DESIGN AND 1001 Home Ideas 6/1/1991 6/1/1991 Magazines Family Media, Inc. DECORATION 3/1/2002- 3/1/2002- Oxford Publishing 20 Century British History 7/1/2009 7/1/2009 Scholarly Journals Limited(England) HISTORY--HISTORY OF EUROPE 33 Charts [33 Charts - 12/12/2009 12/12/2009- 12/12/2009 BLOG] + 6/3/2011 + Other Resources Newstex CHILDREN AND YOUTH--ABOUT COMPUTERS--INFORMATION 50+ Digital [50+ Digital, 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- SCIENCE AND INFORMATION LLC - BLOG] 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 Other Resources Newstex THEORY IDG 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- Communications/Peterboro COMPUTERS--PERSONAL 80 Micro 6/1/1988 6/1/1988 Magazines ugh COMPUTERS 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 Australian Associated GENERAL INTEREST PERIODICALS-- AAP General News Wire + + + Wire Feeds Press Pty Limited UNITED STATES AARP Modern Maturity; 2/1/1988- 2/1/1988- 2/1/1991- American Association of [Library edition] 1/1/2003 1/1/2003 11/1/1997 Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS American Association of AARP The Magazine 3/1/2003+ 3/1/2003+ Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS ABA Journal 8/1/1972+ 1/1/1988+ 1/1/1992+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW ABA Journal of Labor & Employment Law 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW MEDICAL SCIENCES--NURSES AND ABNF Journal 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ Scholarly Journals Tucker Publications, Inc. -

Self-Publishing and Collection Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries Robert P

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 9-15-2015 Self-Publishing and Collection Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries Robert P. Holley Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, and the Collection Development and Management Commons Recommended Citation Holley, Robert P., Self-Publishing and Collection Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries. (2015). Purdue University Press. (Knowledge Unlatched Open Access Edition.) This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Self-Publishing and Collection Development Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries Charleston Insights in Library, Archival, and Information Sciences Editorial Board Shin Freedman Tom Gilson Matthew Ismail Jack Montgomery Ann Okerson Joyce M. Ray Katina Strauch Carol Tenopir Anthony Watkinson Self-Publishing and Collection Development Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries Edited by Robert P. Holley Charleston Insights in Library, Archival, and Information Sciences Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright 2015 by Purdue University. All rights reserved. Cataloging-in-Publication data on file at the Library of Congress. Contents Foreword i Mitchell Davis (BiblioLabs) Introduction 1 Robert P. Holley (Wayne State University) 1 E-Book Self-Publishing and the Los Gatos Library: A Case Study 5 Henry Bankhead (Los Gatos Library) 2 Supporting Self-Publishing and Local Authors: From Challenge to Opportunity 21 Melissa DeWild and Morgan Jarema (Kent District Library) 3 Do Large Academic Libraries Purchase Self-Published Books to Add to Their Collections? 27 Kay Ann Cassell (Rutgers University) 4 Why Academic Libraries Should Consider Acquiring Self-Published Books 37 Robert P. -

Participating Publishers

Participating Publishers 1105 Media, Inc. AB Academic Publishers Academy of Financial Services 1454119 Ontario Ltd. DBA Teach Magazine ABC-CLIO Ebook Collection Academy of Legal Studies in Business 24 Images Abel Publication Services, Inc. Academy of Management 360 Youth LLC, DBA Alloy Education Aberdeen Journals Ltd Academy of Marketing Science 3media Group Limited Aberdeen University Research Archive Academy of Marketing Science Review 3rd Wave Communications Pty Ltd Abertay Dundee Academy of Political Science 4Ward Corp. Ability Magazine Academy of Spirituality and Professional Excellence A C P Computer Publications Abingdon Press Access Intelligence, LLC A Capella Press Ablex Publishing Corporation Accessible Archives A J Press Aboriginal Multi-Media Society of Alberta (AMMSA) Accountants Publishing Co., Ltd. A&C Black Aboriginal Nurses Association of Canada Ace Bulletin (UK) A. Kroker About...Time Magazine, Inc. ACE Trust A. Press ACA International ACM-SIGMIS A. Zimmer Ltd. Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Fisicas y Acontecimiento A.A. Balkema Publishers Naturales Acoustic Emission Group A.I. Root Company Academia de Ciencias Luventicus Acoustical Publications, Inc. A.K. Peters Academia de las Artes y las Ciencias Acoustical Society of America A.M. Best Company, Inc. Cinematográficas de España ACTA Press A.P. Publications Ltd. Academia Nacional de la Historia Action Communications, Inc. A.S. Pratt & Sons Academia Press Active Interest Media A.S.C.R. PRESS Academic Development Institute Active Living Magazine A/S Dagbladet Politiken Academic Press Acton Institute AANA Publishing, Inc. Academic Press Ltd. Actusnews AAP Information Services Pty. Ltd. Academica Press Acumen Publishing Aarhus University Press Academy of Accounting Historians AD NieuwsMedia BV AATSEEL of the U.S. -

Metadata in the Context of the European Library Project

DC-2002: METADATA FOR E-COMMUNITIES: SUPPORTING DIVERSITY AND CONVERGENCE 2002 Proceedings of the International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata for e-Communities, 2002 October 13-17, 2002 - Florence, Italy Organized by: Associazione Italiana Biblioteche (AIB) Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze (BNCF) Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI) European University Institute (IUE) Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza (IMSS) Regione Toscana Università degli Studi di Firenze DC-2002 : metadata for e-communities : supporting diversity and con- vergence 2002 : proceedings of the International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata for E-communities, 2002, October 13-17, 2002, Florence, Italy / organized by Associazione italiana biblioteche (AIB) … [at al.]. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2002. http://epress.unifi.it/ ISBN 88-8453-043-1 025.344 (ed. 20) Dublin Core – Congresses Cataloging of computer network resources - Congresses Print on demand is available © 2002 Firenze University Press Firenze University Press Borgo Albizi, 28 50122 Firenze, Italy http://epress.unifi.it/ Printed in Italy Proc. Int. Conf. on Dublin Core and Metadata for e-Communities 2002 © Firenze University Press DC-2002: Metadata for e-Communities: Supporting Diversity and Convergence DC-2002 marks the tenth in the ongoing series of International Dublin Core Workshops, and the second that includes a full program of tutorials and peer-reviewed conference papers. Interest in Dublin Core metadata has grown from a small collection of pioneering projects to adoption by governments and international organ- izations worldwide. The scope of interest and investment in metadata is broader still, however, and finding coherence in this rapidly growing area is challenging. The theme of DC-2002 — supporting diversity and convergence — acknowledges these changes. -

Situating Constructionism1

Centro Latinoamericano para la Competitividad y el Desarrollo Sostenible MIT Media Lab Situating Constructionism1 By Seymour Papert and Idit Harel 1 El objetivo de este documento es fomentar la discusión, más que ilustrar el manejo correcto o incorrecto de una situación administrativa. Fue elaborado para ser utilizado en el marco de las actividades a desarrollar en el programa INCAE Digital Nations. INCAE. Alajuela, mayo del 2002 Distribución restringida Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial. Situating Constructionism By Seymour Papert and Idit Harel The following essay is the first chapter in Seymour Papert and Idit Harel's book Constructionism (Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1991). It is easy enough to formulate simple catchy versions of the idea of constructionism; for example, thinking of it as "learning-by-making." One purpose of this introductory chapter is to orient the reader toward using the diversity in the volume to elaborate--to construct--a sense of constructionism much richer and more multifaceted, and very much deeper in its implications, than could be conveyed by any such formula. My little play on the words construct and constructionism already hints at two of these multiple facets--one seemingly "serious" and one seemingly "playful." The serious facet will be familiar to psychologists as a tenet of the kindred, but less specific, family of psychological theories that call themselves contructivist. Constructionism--the N word as opposed to the V word--shares constructivism's connotation of learning as "building knowledge structures" irrespective of the circumstances of the learning. It then adds the idea that this happens especially felicitously in a context where the learner is consciously engaged in constructing a public entity, whether it's a sand castle on the beach or a theory of the universe. -

References 247

References 247 REFERENCES Abernathy, W. & Clark, K. (1985), ‘Mapping the winds of creative destruction.’ Research Policy,14, 3-22. Abramowitz, M. (1956), “Resource and output trends in the United States since 1870”, American Economic Re view 46, 5-23. Abramovitz, M. & David, P. A. (1996), “Technological change and the rise of intangible investments.The U.S. economy’s growth-path in the twentieth century”, in Employment and Growth in the Knowledge-Based Economy, OECD, Paris, 35-60. Ackoff, R. L. (1989), “From Data to Wisdom”, Journal of Applied Systems Analysis, 16, 3-9. Afgan, N. H. & Carvalho, M. G. (2010),“The Knowledge Society: A Sustainability Paradigm”, Cadmus, 1(1), 28-41. Afanas’yev, M. & Myasnikova, L. (2005), “Mirovaya konkurentsiya i klasterizatsiya”, Voprosy ekonomiki, No 4, 75-87. Adler, P. S. & Kwon, S-W. (2002), “Social Capital: Prospects for a New Concept”,The Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17-40. Aggestam, L. (2006), „Learning Organization or Knowledge Management – Which Came First, The Chicken or the Egg?“, Information Technology and Control, 35(3A), 295-302. AIM (2004), I- works: How high value innovation networks can boost UK productivity, ESRC/EPSRC Advanced Institute of Management Research: London Akerlof, G. (1970), “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488-500. Аlle, М. (1979), „Jedinstvennij kriterij istini – soglasije s dannimi opita“, Мirovaja ekonomika i mezdunarodnie otnosenija, 11, 25-29. American Productivity and Quality Center (2000), “Building and sustaining com-mu- nities of practice: continuing success in knowledge management”, American Productivity and Quality Center, http://www.apqc.org/ proposal/6576km6/ (downloaded 12.01.2011) American Productivity and Quality Center(2000a),Knowledge Management: A Guide for Your Journey to Best-Practice Processes, APQC, Houston, Texas. -

Impact of Reporter Work Role Identity on News Story Source Selection: Implications for Coverage of Agricultural Crises

Journal of Applied Communications Volume 93 Issue 3 Nos. 3 & 4 Article 3 Impact of Reporter Work Role Identity on News Story Source Selection: Implications for Coverage of Agricultural Crises Judith McIntosh White Tracy Rutherford Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/jac This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. Recommended Citation White, Judith McIntosh and Rutherford, Tracy (2009) "Impact of Reporter Work Role Identity on News Story Source Selection: Implications for Coverage of Agricultural Crises," Journal of Applied Communications: Vol. 93: Iss. 3. https://doi.org/10.4148/1051-0834.1197 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Applied Communications by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Impact of Reporter Work Role Identity on News Story Source Selection: Implications for Coverage of Agricultural Crises Abstract This study examined coverage of the December 2003 bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) event to discover impact of reporters’ work role identities on news story source choices and to explore implications of results for agricultural crisis coverage. Content analysis was performed on 62 stories from U.S. newspapers in the Lexis Nexis database, selected through keyword search December 23, 2003 through October 31, 2004. These stories were divided into two equal groups based on reporters’ work-role identity (dichotomized between science-specialty beat reporters and non-specialty reporters) and analyzed by length, number of sources, and source variety. -

Teaching Resources Guide for Public Affairs and Administration

Teaching Resources Guide for Public Affairs and Administration Fourth Edition Marc Holzer, Co-Editor Lois M. Warner, Co-Editor Dan Bee Lee, Associate Editor NASPAA’s Teaching Resources Guide for Public Affairs and Administration, Fourth Edition, developed by the School of Public Affairs and Administration (SPAA) at Rutgers University-Newark, brings together a broad array of teaching and learning resources on public policy, public affairs and administration and makes each available via a web link. The guide comprises web links to over 2500 resources and technologies. These include a recent selection of textbooks, journals, media, curricula, and lesson plans, and cases for the class discussion, from well-known sources, such as the Public Administration Gateway (PA Gateway). The fourth edition has some new sections that cover links to software packages for data analysis, video editing, and creating surveys and diagrams. The sections on teaching research methods, simulations, classroom management, learning outcomes and student evaluation were revised and updated. ii Teaching Resources Guide for Public Affairs and Administration Fourth Edition Co-Editors Marc Holzer, PhD Dean Emeritus and University Professor School of Public Affairs and Administration (SPAA) Rutgers University-Newark Lois M. Warner, PhD Assistant Teaching Professor, Teaching Resources Coordinator School of Public Affairs and Administration (SPAA) Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey-Newark Dan Bee Lee, MPA Doctoral Research Assistant School of Public Affairs and Administration (SPAA) Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey-Newark Contributors We wish to acknowledge the assistance provided for previous editions by faculty, doctoral students, and staff at the School of Public Affairs and Administration (SPAA), Rutgers University-Newark: Tugba Aksoy, Jeffrey Backstrand, Michael Gershowitz, Peter Hoontis, Quintus Jett, Dongyeon Kang, Kelly Robinson, Jongmin Shon, Ginger Swiston, and Roberta Tipton. -

Reference and Domain

EMOTIONAL SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS PARENT-CHILD SYSTEM EDUCATIONAL ASSESSMENT FAMILY INTERVENTIONS PREVENTION / REFERENCE AND DOMAIN Achenbach, T. M. (1997). What is normal? what is abnormal? developmental perspectives on behavioral and emotional prob- lems. In S. S. Luthar, & J. A. Burack (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Perspectives on adjustment, risk, and disorder (pp. 93-114). New York: Cambridge University Press. Anastasiow, N. J. (1990). Implications of the neurobiological model for early intervention. In S. J. Meisels, & J. P. Shonkoff (Eds.), Handbook of early childhood intervention.; handbook of early childhood intervention (pp. 196-216). New York: Cambridge University Press. August, G. J., Lee, S. S., Bloomquist, M. L., Realmuto, G. M., & Hektner, J. M. (2003). Dissemination of an evidence-based preven- tion innovation for aggressive children living in culturally diverse, urban neighborhoods: The early risers effectiveness study. Prevention Science, 4(4), 271-286. Bagnato, S. J., Suen, H. K., Brickley, D., Smith-Jones, J., & Dettore, E. (2002). Child developmental impact of pittsburgh’s early childhood initiative (ECI) in high-risk communities: First-phase authentic evaluation research. Early Childhood Research Quar- terly, 17(4), 559-580. Bailey, D. B. J., Aytch, L. S., Odom, S. L., Symons, F., & Wolery, M. (1999). Early intervention as we know it. Mental Retardation & Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 5(1), 11-20. Bailey, D. B., Burchinal, M. R., & McWilliam, R. A. (1993). Age of peers and early development. Child Development, 64(3), 848- 862 Baker, B.L., Feinfield, K.A., (2003). Early intervention.Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 16(5), 503-509. Barnett, D. W., Bell, S. H., Bauer, A., Lentz, F. -

Clark, H.H. Marshall, C. Definite Reference and Mutual Knowledge

In,A.K. Joshi, B. L. Webber, and I.A. Sag (Eds. ) , Elements of Discourse Understanding. Cambridge: Defii~itereference aid mutud krlowledge 11 Cambridge University Press, 1981. about, it was that noun phrases like ~heseare ordil~arilyselected in ;I fittile amount of titile - in a few seconds or less. We were at an impasse. Tlie argument for an infinite amoutlt of processing time seemed im- Definite reference and mutual peccable, but so did the evidence against it. What we had was a pro- cessing paradox, which for reasons that will become clear later wc knowledge called the i~~ulunlhiwwle(1ge pnmdox. like all paradoxes, of' course, this one rests on several critical as- sumptions, and when these assun~ptionsare weakened in one way or HERBERT .H. CLARK and CATHERINE K. another, the paradox can be resolved in several ways. These differer~t MARSHALL resolutions, however, each have their own consequences, and depend- ing on which one we accept, we are led to rather different models for ~ack'thinks the production and understanding of speech. It is important to de- he does ~iot'know what lie thinks cide, then, which way the mutual knowledge paradox is most plausibly 111 thinks resolvetl. d e does not know But we ;Ire interested in this paradox only as a way of getting at the 13ut Jill tllinks Jack does know it. two cetl~ralquestions of this chapter: (a) What type of shared knowl- So Jill does not know edge is needed for language use? and (b) how is that shared kr~owl- she does not know edge in practice assessed and secured? The area of' language in which we will take up these questions is definite referel~ce,I~ut eve11 our interest in definite reference is secondary to our concern with the two questions of mutual knowledge. -

Access to the Law in Canada in the Digital Age

ACCESS TO LAW-RELATED INFORMATION IN CANADA IN THE DIGITAL AGE by Theodore John Tjaden A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Law Faculty of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by Theodore John Tjaden 2005 Access To Law-Related Information In Canada In The Digital Age LL.M. 2005 Theodore John Tjaden Faculty of Law, University of Toronto Abstract Access to law-related information in Canada is – and should be – a fundamental right. This access is crucial in a democracy such as Canada that follows the rule of law since access to legislation, case law and other government information that is law-related is essential for an informed citizenry. However, a number of factors negatively impact this access, including the complexity of the Canadian legal system, the small size of the Canadian legal publishing industry, Crown copyright, contradictory government information policies, and a shrinking public domain through the digitization of information and other roadblocks on the Internet. The stakeholders involved – the government, private publishers, lawyers, law schools, and other public interest groups – have important roles to play in improving access, particularly through the use of Internet technologies. Recommendations are therefore included regarding specific steps that can be taken to improve access to law-related information in Canada in the digital age. ii Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge the continual support of my wife Reiko and daughter Hannah in their encouragement and support that allowed me to work on my Master’s of Law thesis. I could not have done it without them.