The Story of Rose Bower : Exegesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOOKS: the Hand That Feeds You, a Novel (Co-Authored with Amy Hempel)

BOOKS: The Hand That Feeds You, a novel (co-authored with Amy Hempel) Scribner (published in 2015) Act of God± a novel Pantheon (published in 2015) Vintage Contemporary Paperback (published in 2016) Pushkin Press, England (published 2016) 5 Flights Up, an adaptionHeroic of Measures Revelations Entertainment Latitude Productions Directed by Richard Loncraine Starring Morgan Freeman, Diane Keaton, and Cynthia Nixon Scheduled release date: 2015 Heroic Measures, a novel Pantheon (published in 2009) Vintage Contemporary Paperback (published in 2010) Schocken Books, Israel (2010) Prószyński Media, Poland (2014) Newton & Compton Editions, Italy (2015) AST publications, Russia (2015) Pushkin Press, Great Briton (2015) The Tattoo Artist1 a novel Pantheon (published in 2005) Vintage Contemporary Paperback Verso da Kapa, Portugal East View International Culture LTD, Taiwan Teeth of the Dogx a novel Crown/Random House (published in 1999) Bertelsmann, Germany Half a Life, a memoir Crown/Random House (published in 1996) Anchor Books The Law of Falling Bodies± a novel Poseidon Press/Simon & Schuster (published in 1993) Kruger Verlag, Germany Money, a novella Kruger Verlag, Germany (published in 1993) Small Claims± a collection of short stories Weidenfeld & Nicolson, New York (published in 1986) Flammarion Editions, France Bompiani Editions, Italy FELLOWSHIPS / AWARDS: Los Angeles Times Best Fiction Award Finalist(Heroic Measures) 2010 Globe and the Mail Best International Fiction(Heroic Award Measures) 2010 Janet Fleidenger Kafka Prize for best fiction by an American woman ( The Tattoo Artist) 2006 Guggenheim Fellowship 2006 New York State Foundation for the Arts in Creative Writing 2002 National Endowment for the Arts/Japan Fellowship 1999 New York State Foundation for the Arts in Creative Writing 1996 National Endowment for the Arts in Creative Writing 1995. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/97g9d23n Author Mewhinney, Matthew Stanhope Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki By Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Alan Tansman, Chair Professor H. Mack Horton Professor Daniel C. O’Neill Professor Anne-Lise François Summer 2018 © 2018 Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney All Rights Reserved Abstract The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki by Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language University of California, Berkeley Professor Alan Tansman, Chair This dissertation examines the transformation of lyric thinking in Japanese literati (bunjin) culture from the eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. I examine four poet- painters associated with the Japanese literati tradition in the Edo (1603-1867) and Meiji (1867- 1912) periods: Yosa Buson (1716-83), Ema Saikō (1787-1861), Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902) and Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916). Each artist fashions a lyric subjectivity constituted by the kinds of blending found in literati painting and poetry. I argue that each artist’s thoughts and feelings emerge in the tensions generated in the process of blending forms, genres, and the ideas (aesthetic, philosophical, social, cultural, and historical) that they carry with them. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term. -

18416.Brochure Reprint

RANDOMRANDOM HOUSEHOUSE PremiumPremium SalesSales && CustomCustom PublishingPublishing Build Your Next Promotion with THE Powerhouse in Publishing . Random House nside you’ll discover a family of books unlike any other publisher. Of course, it helps to be the largest consumer book publisher in the world, but we wouldn’t be successful in coming up with creative premium book offers if we didn’t have Ipeople who understand what marketers need. Drop in and together we’ll design your blueprint for success. Health & Well-Being You’re in good hands with a medical staff that includes the American Heart Association, American Medical Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Cancer Society, Dr. Andrew Weil and Deepak Chopra. Millions of consumers have received our health books through programs sponsored by pharmaceutical, health insurance and food companies. Travel Targeting the consumer or business traveler in a future promotion? Want the #1 brand name in travel information? Then Fodor’s, with its ever-expanding database to destina- tions worldwide, is the place to be. Talk to us about how to use Fodor’s books for your next convention or meeting and even about cross-marketing opportunities and state-of- the-art custom websites. If you need beauti- fully illustrated travel books, we also publish the Knopf Guides, Photographic Journey and other picture book titles. Call 1.800.800.3246 Visit us on the Web at www.randomhouse.com 2 Cooking & Lifestyle Imagine a party with Julia Child, Martha Stewart, Jean-Georges, and Wolfgang Puck catering the affair. In our house, we have these and many more award winning chefs and designers to handle all the details of good living. -

An Archipelago of Readers: the Beginnings of Archipelago and International Publishing on the World Wide Web

An Archipelago of Readers: The Beginnings of Archipelago and International Publishing on the World Wide Web Katherine McNamara A Talk Given at University of Trier, English and Media Studies Departments May 24, 2005 Precarious In 1989, did we realize that the twentieth century ended? The world had changed; the change began, I would say, on February 14 that year, when the nation of Iran issued a fatwa, a death-sentence, against the novelist Salman Rushdie. He was an Indian citizen with an international reputation living in London, and he was sentenced to death by a foreign government for a work of fiction. That was a terrible shock and sent fear instantly through writers everywhere in the world. I wonder if we recall that fear now. We should recall it. Its memory has affected all of literary life, in that we can no longer believe without question that free speech is indivisible in a civilized, democratic society. In those years I lived in New York and had a book contract with Viking, Rushdie's American publisher. My editor told me that the chief officers of Viking had for a month eaten and slept in different hotels every night for safety, and that the cost of defending the Viking operations was more than a million dollars. (In July 1991, Rushdie's Japanese 1 Katherine McNamara Institutional Memory and the Prospect of Publishing translator would be killed, his Italian translator wounded; in October 1993, his Norwegian publisher would be shot and seriously injured. Rushdie had been put at once into protective custody by the British MI5 and would be guarded for the next ten years, until the fatwa was cancelled, if that is the proper verb.) It was a peculiar moment privately, too, because the book I was writing was about Alaska, and about my work as an itinerant poet among Native people in Alaska. -

American Discourses on Jewishness After the Second World War (1945-49) Samantha M

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2013 "We long for a home": American discourses on Jewishness after the Second World War (1945-49) Samantha M. Bryant James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Samantha M., ""We long for a home": American discourses on Jewishness after the Second World War (1945-49)" (2013). Masters Theses. 162. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/162 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “We Long For a Home”: American Discourses on Jewishness After the Second World War (1945-49) Samantha M. Bryant A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2013 To my late grandfather whose love for history and higher education continues to inspire my work. Despite having never entered a college classroom, he was, and continues to be, the greatest professor I ever had. ii Acknowledgments The seeds of this project were sown in the form of a term paper for an undergraduate course on the history and politics of the Middle East at Lynchburg College with Brian Crim. His never-ending mentorship and friendship have shaped my research interests and helped prepare me for the trials and tribulations of graduate school. -

Books Received

Books Received Jewish Quarterly Review, Volume 99, Number 4, Fall 2009, (Article) Published by University of Pennsylvania Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jqr.0.0070 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/363505 [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] T HE J EWISH Q UARTERLY R EVIEW, Vol. 99, No. 4 (Fall 2009) H AGNON,S.Y.A Book That Was Lost: Thirty-Five Stories. Expanded edi- tion including all stories from Twenty-One Stories. New Milford, Conn.: Toby Press, 2008. A LBERT,ELISA. How This Night Is Different. New York: Free Press, 2008. A LEXANDER,PHILIP S. The Targum of Lamentations. Translated with a critical introduction, apparatus, and notes. The Aramaic Bible 17B. Col- legeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, 2007. A LTSHULER,MORDECHAI. Judaism in the Soviet Vise: Between Religion and Jewish Identity in the Soviet Union, 1941–1964. (Hebrew). Jerusalem: Zalman Shazar Center for Jewish History, 2007. A RANDA,MARIANO G O´ MEZ. Dos Commentarios de Abraham Ibn Ezra al Libro de Ester. Edicio´n crı´tica, traduccio´n y studio introductorio. Serie A: Literatura Hispano-Hebrea 9. Madrid: Consejo superior de Investigaci- ones Cientı´ficas Instituto de Filologı´a, 2007. A SCHER,ABRAHAM. A Community under Siege: The Jews of Breslau under Nazism. Stanford Studies in Jewish History and Culture. Stanford, Calif.: BOOKS RECEIVED 2008 Stanford University Press, 2007. AVINERI,SHLOMO. Herzl. (Hebrew). Jerusalem: Zalman Shazar Cen- ter, 2007. BASKIND,SAMANTHA AND R ANEN O MER-SHERMAN, EDS. The Jew- ish Graphic Novel: Critical Approaches. -

Ekonomska Učinkovitost Globalnih Medijskih Konglomeratov

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Marija Igerc Ekonomska učinkovitost globalnih medijskih konglomeratov Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2015 UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Marija Igerc Mentor: red. prof. dr. Borut Marko Lah Ekonomska učinkovitost globalnih medijskih konglomeratov Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2015 Ekonomska učinkovitost globalnih medijskih konglomeratov V zadnjih tridesetih letih so prevzemi in spojitve postali ena najpogostejših strategij podjetij v medijski industriji. Mnogi avtorji takšno združevanje medijskih podjetij povezujejo z maksimiranjem dobička, saj naj bi se na ta način povečala tako tržna moč kot tudi učinkovitost poslovanja podjetij. V diplomskem delu trdim, da koncentrirano medijsko lastništvo ne povečuje ekonomske učinkovitosti kapitala. Sinergije ne prinašajo pričakovanih izjemnih dobičkov. Doseg diplomskega dela ni tako velik, da bi lahko sama izvedla kvantitativno analizo največjih globalnih medijskih konglomeratov, zato sem ga napisala pretežno teoretično, ob tem pa sem se naslonila na nekaj mednarodno objavljenih študij. Rezultati delno podpirajo mojo prvotno hipotezo, saj so pokazali, da nekateri ekonomski kazalniki ne kažejo boljših rezultatov v tistih medijskih podjetjih, v katerih se je kapital v veliki meri združeval in koncentriral. Zdi se, da so megamedijske združitve za marsikoga razočaranje. Ključne besede: medijska industrija, prevzemi in spojitve, medijski konglomerati, koncentracija lastništva, sinergije. Economic efficiency of global media conglomerates In the past thirty years, acquisitions and mergers have become one of the most common strategies of companies in the media industry. Many authors associate such integration of media companies with profit maximization, since it should increase market power and efficiency of business operations. In the thesis I argue that concentrated media ownership does not increase the economic efficiency of capital. -

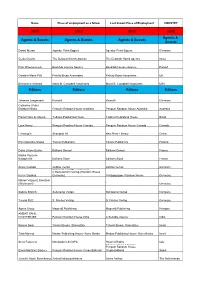

2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents

Name Place of employment as a fellow Last known Place of Employment COUNTRY 2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Scouts Daniel Mursa Agentur Petra Eggers Agentur Petra Eggers Germany Geula Geurts The Deborah Harris Agency The Deborah Harris Agency Israel Piotr Wawrzenczyk Book/lab Literary Agency Book/lab Literary Agency Poland Caroline Mann Plitt Felicity Bryan Associates Felicity Bryan Associates UK Beniamino Ambrosi Maria B. Campbell Associates Maria B. Campbell Associates USA Editors Editors Editors Editors Johanna Langmaack Rowohlt Rowohlt Germany Catherine (Cate) Elizabeth Blake Penguin Random House Australia Penguin Random House Australia Australia Flavio Rosa de Moura Todavia Publishing House Todavia Publishing House Brazil Lynn Henry Penguin Random House Canada Penguin Random House Canada Canada Li Kangqin Shanghai 99 New River Literary China Päivi Koivisto-Alanko Tammi Publishers Tammi Publishers Finland Dana Liliane Burlac Éditions Denoël Éditions Denoël France Maÿlis Vauterin- Bacqueville Editions Stock Editions Stock France Anvar Cukoski Aufbau Verlag Aufbau Verlag Germany Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt and C.Bertelsmann Verlag (Random House Karen Guddas Germany) Verlagsgruppe Random House Germany Marion Vazquez Boerzsei (Wichmann) ` ` Germany Sabine Erbrich Suhrkamp Verlag Suhrkamp Verlag Germany Teresa Pütz S. Fischer Verlag S. Fischer Verlag Germany Ágnes Orzóy Magvető Publishing Magvető Publishing Hungary AMBAR SAHIL CHATTERJEE Penguin Random House India A Suitable Agency India Ronnie -

Rodchenko in Paris

Rodchenko in Paris CHRISTINA KIAER "The light from the East is not only the liberation of workers," the Russian Constructivist Aleksandr Rodchenko wrote in a letter home from Paris in 1925, "the light from the East is in the new relation to the person, to woman, to things. Our things in our hands must be equals, comrades, and not these black and mournful slaves, as they are here."' Rodchenko was in Paris on his first and only trip abroad to arrange the Soviet section of the Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels, for which he built his most famous Constructivist "thing," the Workers' Club interior. His lucidly spare, geometric club embodies the rational- ized utilitarian object of everyday life proposed at this time by Russian Constructivist artists and Lef theorists such as Boris Arvatov. And Rodchenko's invocation of the socialist object from the East as a "comrade" corresponds to Arvatov's theory of the new industrial object as an active "co-worker" in the construction of socialist life, in contrast to the passive capitalist commodity-Rodchenko's "black and mournful slaves"-oriented toward display and exchange.2 Yet there is something uncanny about the stark, constrained order of the Workers' Club that exceeds Arvatov's theory, a visual uncanny that corresponds to the curious intensity and pathos of Rodchenko's verbal plea for "our things in our hands." In this essay I want to propose that the language of Rodchenko's letters and the visual forms of his club elaborate, in a more subjective register, upon the Constructivist theory of the object-an elaboration that endows that object with a body and places it within the field of desire that is organized, under capitalism, by the commodity form. -

Claims Resolution Tribunal

CLAIMS RESOLUTION TRIBUNAL In re Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation Case No. CV96-4849 Certified Award to Claimant [REDACTED 1] also acting on behalf of [REDACTED 2], [REDACTED 3], [REDACTED 4], [REDACTED 5], [REDACTED 6], [REDACTED 7], [REDACTED 8], [REDACTED 9], [REDACTED 10], [REDACTED 11], [REDACTED 12], [REDACTED 13], [REDACTED 14], [REDACTED 15], [REDACTED 16], [REDACTED 17] and [REDACTED 18] in re Accounts of Lilli Schocken and Einkaufszentrale I. Schocken Söhne GmbH Claim Numbers: 005317/RS; 005318/RS Award Amount: 487,500.00 Swiss Francs This Certified Award is based upon the claims of [REDACTED 1], née [REDACTED], (the Claimant ) to the accounts of Salman Schocken and Lilli Schocken.1 This Award is to the published account of Lilli Schocken ( Account Owner Schocken ), over which Salmann Schocken and Einkaufszentrale I. Schocken Söhne GmbH held power of attorney, at the Basel branch of the [REDACTED] (the Bank ); and to the unpublished accounts of Account Owner Schocken and Account Owner Einkaufszentrale I. Schocken Söhne GmbH ( Account Owner Einkaufszentrale ) at the Bank. All awards are published, but where a claimant has requested confidentiality, as in this case, the names of the claimant, any relatives of the claimant other than the account owner, and the bank have been redacted. Information Provided by the Claimant The Claimant submitted a Claim Form identifying Account Owner Schocken as her grandmother, Lilli (Zerline) Schocken, who was born on 30 June 1889 in Frankfurt, Germany, and was married on 5 April 1910 to Salman (Salmann) Schocken, whom she identified as Power of Attorney holder Salman Schocken. The Claimant stated that Lilli Schocken had five children: [REDACTED] (the Claimant s father); [REDACTED]; [REDACTED], née [REDACTED]; [REDACTED]; and [REDACTED], all of whom have passed away.