International Court of Justice 3 0 .I a = Filed in the Registry on : 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Student Officers: President: Mohamed El Habbak Chairs: Adam Beblawy, Ibrahim Shoukry

Forum: Security Council Issue: The Israeli-Palestinian conflict Student Officers: President: Mohamed El Habbak Chairs: Adam Beblawy, Ibrahim Shoukry Introduction: Beginning in the mid-20th century, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is the still continuing dispute between Israel and Palestine and part of the larger Arab-Israeli conflict, and is known as the world’s “most intractable conflict.” Despite efforts to reach long-term peace, both parties have failed to reach a final agreement. The crux of the problem lies in a few major points including security, borders, water rights, control of Jerusalem, Israeli settlements, Palestinian freedom of movement, and Palestinian right of return. Furthermore, a hallmark of the conflict is the level of violence for practically the entirety of the conflict, which hasn’t been confined only to the military, but has been prevalent in civilian populations. The main solution proposed to end the conflict is the two-state solution, which is supported by the majority of Palestinians and Israelis. However, no consensus has been reached and negotiations are still underway to this day. The gravity of this conflict is significant as lives are on the line every day, multiple human rights violations take place frequently, Israel has an alleged nuclear arsenal, and the rise of some terroristic groups and ideologies are directly linked to it. Key Terms: Gaza Strip: Region of Palestine under Egyptian control. Balfour Declaration: British promise to the Jewish people to create a sovereign state for them. Golan Heights: Syrian territory under Israeli control. West Bank: Palestinian sovereign territory under Jordanian protection. Focused Overview: To understand this struggle, one must examine the origins of each group’s claim to the land. -

2018-2019 Model Arab League BACKGROUND GUIDE Council on Palestinian Affairs Ncusar.Org/Modelarableague

2018-2019 Model Arab League BACKGROUND GUIDE Council on Palestinian Affairs ncusar.org/modelarableague Original draft by Jamila Velez Khader, Chair of the Council on Palestinian Affairs at the 2019 National University Model Arab League, with contributions from the dedicated staff and volunteers at the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations Topic I: Devising strategies to plan for potential failure of peace negotiations. I. Introduction to the Topic A. General Background As early as 1947, Palestinian Arabs and Jews have wanted to undertake peace negotiations under the auspice of the United Nations. However, 1991 was the start of the series of peace negotiations between Israel and Palestine.1 The series of peace negotiations have produced a collection of peace plans, international summits, secret negotiations, UN resolutions, think tanks, initiatives, interim truces and state-building programmes, etc that have all failed. The reasons for why each peace negotiation has faltered is because each peace plan has failed to address key issues at a local, regional and global level for all parties involved. The main players in these negotiations include the Palestinian government, political parties of Palestine, the Israeli State, and members of the Arab League and United Nations. The most recent peace plan between one of Palestine’s prominent political parties, Hamas, which governs Gaza, took place with Israel in Cairo, Egypt. Currently, Egypt is finalizing the details of a one year truce that could extend to four years.2 Although this can be considered progress, it is only short term. A truce up to four years is not sustainable and does not resolve the larger issues at hand which include: Palestinian statehood, border placement, rights of Palestinian refugees and diaspora, Israeli settlements and the role of Arab League and United Nations. -

The Humanitarian Monitor CAP Occupied Palestinian Territory Number 17 September 2007

The Humanitarian Monitor CAP occupied Palestinian territory Number 17 September 2007 Overview- Key Issues Table of Contents Update on Continued Closure of Gaza Key Issues 1 - 2 Crossings Regional Focus 3 Access and Crossings Rafah and Karni crossings remain closed after more than threemonths. Protection of Civilians 4 - 5 The movement of goods via Gaza border crossings significantly Child Protection 6-7 declined in September compared to previous months. The average Violence & Private 8-9 of 106 truckloads per day that was recorded between 19 June and Property 13 September has dropped to approximately 50 truckloads per day 10 - 11 since mid-September. Sufa crossing (usually opened 5 days a week) Access was closed for 16 days in September, including 8 days for Israeli Socio-economic 12 - 13 holidays, while Kerem Shalom was open only 14 days throughout Conditions the month. The Israeli Civil Liaison Administration reported that the Health 14 - 15 reduction of working hours was due to the Muslim holy month Food Security & 16 - 18 of Ramadan, Jewish holidays and more importantly attacks on the Agriculture crossings by Palestinian militants from inside Gaza. Water & Sanitation 19 Impact of Closure Education 20 As a result of the increased restrictions on Gaza border crossings, The Response 21 - 22 an increasing number of food items – including fruits, fresh meat and fish, frozen meat, frozen vegetables, chicken, powdered milk, dairy Sources & End Notes 23 - 26 products, beverages and cooking oil – are experiencing shortages on the local market. The World Food Programme (WFP) has also reported significant increases in the costs of these items, due to supply, paid for by deductions from overdue Palestinian tax increases in prices on the global market as well as due to restrictions revenues that Israel withholds. -

The Mossawa Center's Briefing on the 'Deal of the Century' 1. Political

The Mossawa Center’s Briefing on the ‘Deal of the Century’ 1. Political Background Following two inconclusive rounds of elections in April and September 2019, Israel is set to hold an unprecedented third consecutive election in March 2020. With no clear frontrunner between Benny Gantz of Kahol Lavan (Blue and White) and Benjamin Netanyahu of the Likud, the leaders are locked in a frantic and unrestrained race to the bottom. Trump’s announcement that he would launch the political section of his ‘Peace to Prosperity’ document before the Israeli election has fanned the flames of this right-wing one-upmanship. The timing of the announcement was criticized as a political ploy to benefit his close ally Netanyahu which, against the backdrop of his alleged interference in Ukraine at the crux of his impeachment trial, he was eager to avoid. In the end, both Netanyahu and Gantz visited the White House, but there was only one winner: the sitting prime minister – who, on the day of the announcement, was indicted all three counts of bribery, fraud and breach of trust after withdrawing his request for immunity. It was Netanyahu who unveiled the document alongside the President, forcing Gantz’s hand: in his earlier attempts to cannibalize Netanyahu’s voter base in his pledge to annex the Jordan Valley, he had no choice but to endorse the plan, which could come before the Knesset before the March 2020 election. However, Gantz’s rightward shift has dire ramifications for the next election. Between the April and September elections, turnout among the Palestinian Arab community increased by twelve points, and polls are predicting a further increase. -

Israel in 1982: the War in Lebanon

Israel in 1982: The War in Lebanon by RALPH MANDEL LS ISRAEL MOVED INTO its 36th year in 1982—the nation cele- brated 35 years of independence during the brief hiatus between the with- drawal from Sinai and the incursion into Lebanon—the country was deeply divided. Rocked by dissension over issues that in the past were the hallmark of unity, wracked by intensifying ethnic and religious-secular rifts, and through it all bedazzled by a bullish stock market that was at one and the same time fuel for and seeming haven from triple-digit inflation, Israelis found themselves living increasingly in a land of extremes, where the middle ground was often inhospitable when it was not totally inaccessible. Toward the end of the year, Amos Oz, one of Israel's leading novelists, set out on a journey in search of the true Israel and the genuine Israeli point of view. What he heard in his travels, as published in a series of articles in the daily Davar, seemed to confirm what many had sensed: Israel was deeply, perhaps irreconcilably, riven by two political philosophies, two attitudes toward Jewish historical destiny, two visions. "What will become of us all, I do not know," Oz wrote in concluding his article on the develop- ment town of Beit Shemesh in the Judean Hills, where the sons of the "Oriental" immigrants, now grown and prosperous, spewed out their loath- ing for the old Ashkenazi establishment. "If anyone has a solution, let him please step forward and spell it out—and the sooner the better. -

Palestinian Forces

Center for Strategic and International Studies Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy 1800 K Street, N.W. • Suite 400 • Washington, DC 20006 Phone: 1 (202) 775 -3270 • Fax : 1 (202) 457 -8746 Email: [email protected] Palestinian Forces Palestinian Authority and Militant Forces Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies [email protected] Rough Working Draft: Revised February 9, 2006 Copyright, Anthony H. Cordesman, all rights reserved. May not be reproduced, referenced, quote d, or excerpted without the written permission of the author. Cordesman: Palestinian Forces 2/9/06 Page 2 ROUGH WORKING DRAFT: REVISED FEBRUARY 9, 2006 ................................ ................................ ............ 1 THE MILITARY FORCES OF PALESTINE ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 2 THE OSLO ACCORDS AND THE NEW ISRAELI -PALESTINIAN WAR ................................ ................................ .............. 3 THE DEATH OF ARAFAT AND THE VICTORY OF HAMAS : REDEFINING PALESTINIAN POLITICS AND THE ARAB - ISRAELI MILITARY BALANCE ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .... 4 THE CHANGING STRUCTURE OF PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY FORC ES ................................ ................................ .......... 5 Palestinian Authority Forces During the Peace Process ................................ ................................ ..................... 6 The -

Polio October 2014

Europe’s journal on infectious disease epidemiology, prevention and control Special edition: Polio October 2014 Featuring • The polio eradication end game: what it means for Europe • Molecular epidemiology of silent introduction and sustained transmission of wild poliovirus type 1, Israel, 2013 • The 2010 outbreak of poliomyelitis in Tajikistan: epidemiology and lessons learnt www.eurosurveillance.org Editorial team Editorial advisors Based at the European Centre for Albania: Alban Ylli, Tirana Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), Austria: Reinhild Strauss, Vienna 171 83 Stockholm, Sweden Belgium: Koen De Schrijver, Antwerp Telephone number Belgium: Sophie Quoilin, Brussels +46 (0)8 58 60 11 38 Bosnia and Herzogovina: Nina Rodić Vukmir, Banja Luka E-mail Bulgaria: Mira Kojouharova, Sofia [email protected] Croatia: Sanja Musić Milanović, Zagreb Cyprus: to be nominated Editor-in-chief Czech Republic: Bohumir Križ, Prague Ines Steffens Denmark: Peter Henrik Andersen, Copenhagen Senior editor Estonia: Kuulo Kutsar, Tallinn Kathrin Hagmaier Finland: Outi Lyytikäinen, Helsinki France: Judith Benrekassa, Paris Scientific editors Germany: Jamela Seedat, Berlin Karen Wilson Greece: Rengina Vorou, Athens Williamina Wilson Hungary: Ágnes Csohán, Budapest Assistant editors Iceland: Haraldur Briem, Reykjavik Alina Buzdugan Ireland: Lelia Thornton, Dublin Ingela Söderlund Italy: Paola De Castro, Rome Associate editors Kosovo under UN Security Council Resolution 1244: Lul Raka, Pristina Andrea Ammon, Stockholm, Sweden Latvia: Jurijs Perevoščikovs, -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Israel and the Occupied Territories 2014 Human

ISRAEL 2014 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multi-party parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, the parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “State of Emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve the government and mandate elections. The nationwide Knesset elections in January 2013, considered free and fair, resulted in a coalition government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Security forces reported to civilian authorities. (An annex to this report covers human rights in the occupied territories. This report deals with human rights in Israel and the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights.) During the year a number of developments affected both the Israeli and Palestinian populations. From July 8 to August 26, Israel conducted a military operation designated as Operation Protective Edge, which according to Israeli officials responded to increases in the number of rockets deliberately fired from Gaza at Israeli civilian areas beginning in late June, as well as militants’ attempts to infiltrate the country through tunnels from Gaza. According to publicly available data, Hamas and other militant groups fired 4,465 rockets and mortar shells into Israel, while the government conducted 5,242 airstrikes within Gaza and a 20-day military ground operation in Gaza. According to the United Nations, the operation killed 2,205 Palestinians. The Israeli government estimated that half of those killed were civilians and half were combatants, according to an analysis of data, while the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs recorded 1,483 civilian deaths--more than two-thirds of those killed--including 521 children and 283 women; 74 persons in Israel were killed, among them 67 combatants, six Israeli civilians, and one Thai civilian. -

Learning to Extract International Relations from Political Context

Learning to Extract International Relations from Political Context Brendan O’Connor Brandon M. Stewart Noah A. Smith School of Computer Science Department of Government School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University Harvard University Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA Cambridge, MA 02139, USA Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract model of the relationship between a pair of polit- ical actors imposes a prior distribution over types We describe a new probabilistic model of linguistic events. Our probabilistic model in- for extracting events between major polit- fers latent frames, each a distribution over textual ical actors from news corpora. Our un- expressions of a kind of event, as well as a repre- supervised model brings together famil- sentation of the relationship between each political iar components in natural language pro- actor pair at each point in time. We use syntactic cessing (like parsers and topic models) preprocessing and a logistic normal topic model, with contextual political information— including latent temporal smoothing on the politi- temporal and dyad dependence—to in- cal context prior. fer latent event classes. We quantita- tively evaluate the model’s performance We apply the model in a series of compar- on political science benchmarks: recover- isons to benchmark datasets in political science. ing expert-assigned event class valences, First, we compare the automatically learned verb and detecting real-world conflict. We also classes to a pre-existing ontology and hand-crafted 1 conduct a small case study based on our verb patterns from TABARI, an open-source and model’s inferences. -

Shelter 2014 A3 V1 Majed.Pdf (English)

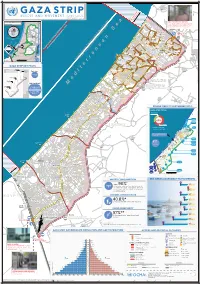

GAZA STRIP: Geographic distribution of shelters 21 July 2014 ¥ 3km buffer Zikim a 162km2 (44% of GaKazrmaiya area) 100,000 poeple internally displaced e Estimated pop. of 300,000 B?4 84,000 taking shelter in UNRWA schools S Yad Mordekhai n F As-Siafa B?4 B?34 Governorate # of IDPs a ID y d e e e h b s a R Netiv ha-Asara Gaza 3 2,401 l- n d A e a c Erez Crossing KhanYunis 9 ,900 r Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) r (Umm An-Naser) fo 4 º» r h ¹ a n 1 al n Middle 7 ,200 S ee 0 l-D e E 2 E t Beit Lahiya 'Izbat Beit Hanoun a t i k k y E a e l- j S North 2 1,986 l B lo l- i a a A m h F a - 34 i u r l B? J A 5! 5! 5! d L t 'Arab Maslakh Madinat al 'Awda i S w Rafah 1 2,717 ta 5! Beit Lahiya r af 5! ! ee g 5! S 5 az Ash Shati' Camp l- 5! W Beit Hanoun e A !5! Al- n 5!5! 5 lil 5!5! Al-q ka ha i uds ek K 5! l-S Grand Total 8 4,204 M h 5!Jabalia A s 5!5! Jabalia Camp i 5!5! D S !x 5!5!5! a a r le a d h Source of data: UNRWA F o m n a 5!5! a r a K J l- a E m l a a l A n b 5! a 5!de Q 5! l l- d N A Gaza e as e e h r s City a R l- A 5!5! 5! 5! s d ! Mefalsim u 5! Q ! 5! l- 5 A 5! A l- M o n a t 232 kk a B? e r l-S A Kfar Aza d a o R l ta s a o C Sa'ad Al Mughraqa arim Nitz ni - (Abu Middein) Kar ka ek n ú S ú 5! e b l- B a A r tt Juhor ad Dik a a m h K O l- ú A ú Alumim An Nuseirat Shuva Camp 5! 5! Zimrat B?25 5! 5! 5! I S R A E L n e e 5! Kfar Maimon D a 5! - k Tushiya l k Al Bureij Camp E e Az Zawayda h S la l- a A S 5! Be'eri !x 5! Deir al Balah Al Maghazi Shokeda Camp 5! 5! Deir al Balah 5!5! Camp Al Musaddar d a o f R la k l a o ta h o 232 -

Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict

Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict September 2000 - September 2007 L_C089061 Table of Contents: Foreword...........................................................................................................................1 Suicide Terrorists - Personal Characteristics................................................................2 Suicide Terrorists Over 7 Years of Conflict - Geographical Data...............................3 Suicide Attacks since the Beginning of the Conflict.....................................................5 L_C089062 Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict Foreword Since September 2000, the State of Israel has been in a violent and ongoing conflict with the Palestinians, in which the Palestinian side, including its various organizations, has carried out attacks against Israeli citizens and residents. During this period, over 27,000 attacks against Israeli citizens and residents have been recorded, and over 1000 Israeli citizens and residents have lost their lives in these attacks. Out of these, 155 (May 2007) attacks were suicide bombings, carried out against Israeli targets by 178 (August 2007) suicide terrorists (male and female). (It should be noted that from 1993 up to the beginning of the conflict in September 2000, 38 suicide bombings were carried out by 43 suicide terrorists). Despite the fact that suicide bombings constitute 0.6% of all attacks carried out against Israel since the beginning of the conflict, the number of fatalities in these attacks is around half of the total number of fatalities, making suicide bombings the most deadly attacks. From the beginning of the conflict up to August 2007, there have been 549 fatalities and 3717 casualties as a result of 155 suicide bombings. Over the years, suicide bombing terrorism has become the Palestinians’ leading weapon, while initially bearing an ideological nature in claiming legitimate opposition to the occupation.