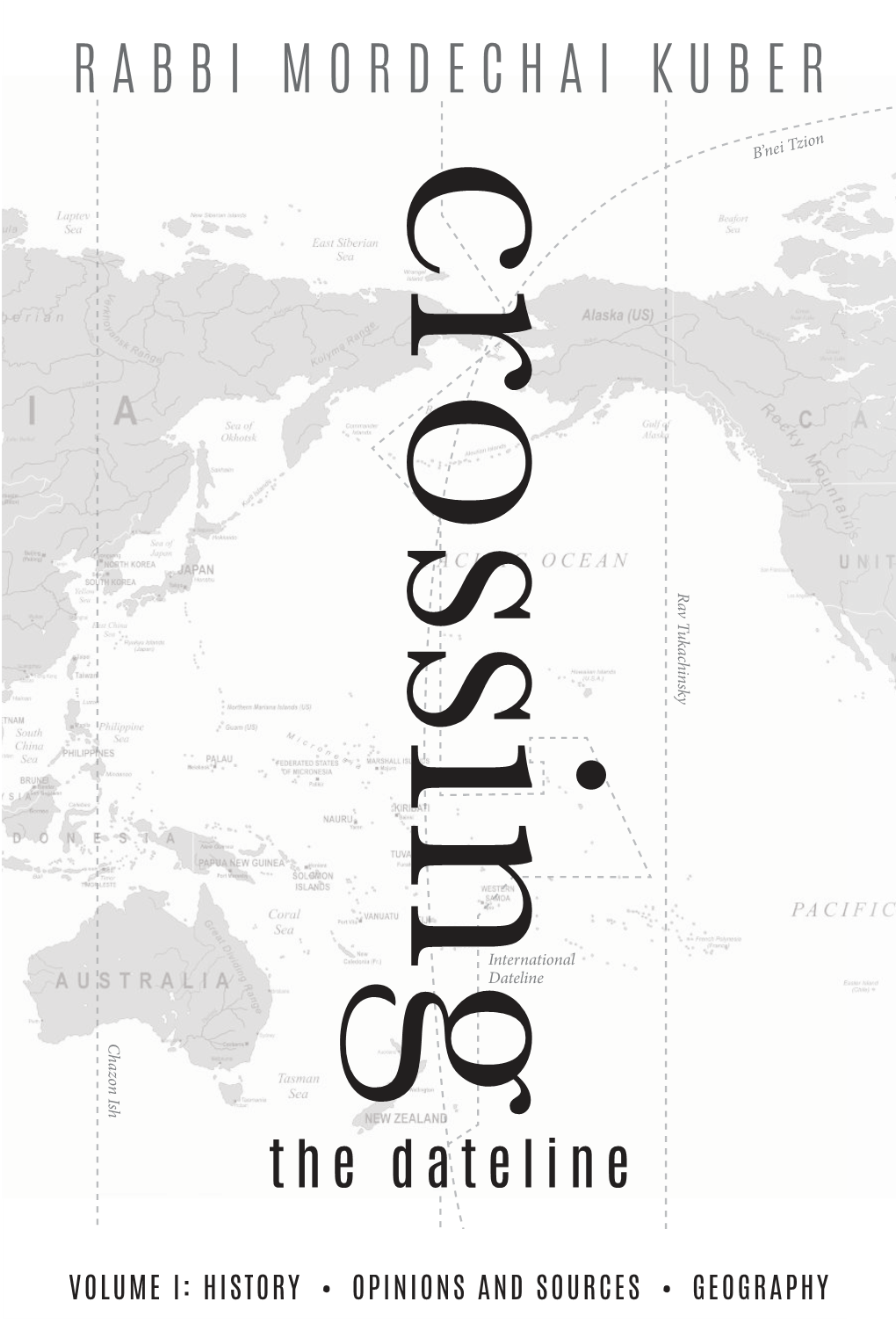

Rabbi Mordechai Kuber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Knessia Gedolah Diary

THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN 0021-6615) is published monthly, in this issue ... except July and August, by the Agudath lsrael of Ameri.ca, 5 Beekman Street, New York, N.Y. The Sixth Knessia Gedolah of Agudath Israel . 3 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N.Y. Subscription Knessia Gedolah Diary . 5 $9.00 per year; two years, $17.50, Rabbi Elazar Shach K"ti•?111: The Essence of Kial Yisroel 13 three years, $25.00; outside of the United States, $10.00 per year Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetzky K"ti•?111: Blessings of "Shalom" 16 Single copy, $1.25 Printed in the U.S.A. What is an Agudist . 17 Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman K"ti•?111: RABBI NISSON WotP!N Editor An Agenda of Restraint and Vigilance . 18 The Vizhnitzer Rebbe K"ti•'i111: Saving Our Children .19 Editorial Board Rabbi Shneur Kotler K"ti•'i111: DR. ERNST BODENHEIMER Chairman The Ability and the Imperative . 21 RABBI NATHAN BULMAN RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS Helping Others Make it, Mordechai Arnon . 27 JOSEPH FRJEDENSON "Hereby Resolved .. Report and Evaluation . 31 RABBI MOSHE SHERER :'-a The Crooked Mirror, Menachem Lubinsky .39 THE JEWISH OBSERVER does not Discovering Eretz Yisroel, Nissan Wolpin .46 assume responsibility for the Kae;hrus of any product or ser Second Looks at the Jewish Scene vice advertised in its pages. Murder in Hebron, Violation in Jerusalem ..... 57 On Singing a Different Tune, Bernard Fryshman .ss FEB., 1980 VOL. XIV, NOS. 6-7 Letters to the Editor . • . 6 7 ___.., _____ -- -· - - The Jewish Observer I February, 1980 3 Expectations ran high, and rightfully so. -

THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN 0021-6615) Is Published Monthly, Except July and August, by the Agudath Israel of America, S Beekman Street, New York, N.Y

Being a ]eve is ~~~;!~ply a '";<"l' of a way of thinkin ,;!its weH!: Ever nccepr thirte~!l,. s. Thhe piled by ~1\q~i: oshe ben make hiI11,a.J!'~'i · . The~Be belief so .. co··. <Jr doubt: Basffolll.< At Rockefeller Center or The Empire State Building UMB Means Business. Commercial banking is easier now that New Yorkers have a choice. They can bank uptown or downtown at UMB Bank & Trust Company. Whether your commercial interests stretch across town or across oceans, UMB crafts its multitude of services to meet your special needs. And, there are so many services-commercial loans, domestic and international money market operations, import· export arrangements, letters of credit and many more. As we are increasing our branches, we are increasing the scope and flexibility of UMB. So, besides adding a new location, we're adding more of the finest commercial and international banking professionals to tailor our services to your business needs. Service and knowledge-it's our special combination that has made us a top choice here in New York and worldwide. Remember, banking with UMB means business. Closed on all Jewish Holidays. /ih'\ UMB BANK ~:I AND TRUST COMPANY Head Office Rockefeller Center Empire State Branch 630 Fifth Avenue 350 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10111 New York, NY 10118 212-541-8070 212·947 ·3611 A subsidiary of Established in 1923 Depositors Now Insured United Mizrahi Bank l TD., Worldw:de Assets Up To $100,000 Israel Exceed $3 Billion Member FDIC THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN 0021-6615) is published monthly, except July and August, by the Agudath Israel of America, S Beekman Street, New York, N.Y. -

This Is the Bais Medrash at Empire Kosher Poultry, Intown, PA@

At this Bais Medrash, not only will you find minyanim for :J"1J1m ,;-rmr.i ,n,1nru, but also shiurim, learning b' chavrusa throughout the day, and a mikvah on premises. This isn't a Bais Medrash in Boro Park, Lakewood or Monsey~ This is the Bais Medrash at Empire Kosher Poultry, intown, PA@ At Empire, this is an essential part of the daily routine. Our Bais Medrash resounds with a ;nm 71p nearly around the clock, whether it's review in Hilchos Shechita, a shiur in Daf Yomi, a masechta h'iyun or in Shmiras Haloshon. What does all of this have to do with kosher chicken? Everything. 10UGH KASHRUS, 1ENDER P0Ul1RY TOLL-FREE CONSUMER HOTLINE: (800) EMPIRE-4 o are observing tz Yisroel this year. be able to sell his lemons this year. He ha§ .. (aith an age. of rapidly e that, like 7 years ago, he ~e •.... <.:r ''i't>i~arket opp~1~~~!~es, the . ~gain. be able tC\ ..%~µ · '· ~~ ~t;aJrigh~rt~ ~te ma~!~P,~C?:n1pes;~trifice to ob~~~ < price next year. But ow doeshelivethis Shmitah:cc~~~f ne,~~ your support,;;• .year? Thanks to the worldwid~. ~upporters encci.)!rrgementand hel~.. :.o make it through · · ofKeren Hashviis, the Centetfor Shmitah the Yt,~t.~ecome~partllet·~: nritzvah which Obs;~~~ Farmers, Ovadi' '' still have a com~~,~~H~.d ?~Y once'lW ~~rs: Answer goo · . · his year. He a~ ~anrily will the~{~f~.. l~~~~~~,e!.:f~ < Torah. ew hardships are as tough to handle as a breadwinner's unemployment. But few hardships are as quickly resolved. FAll it takes is one job to turn a family's worry and strain into peace and security. -

Fashion&Beauty

cx”s Flatbush Jewish Journal The voice of The flaTbush Jewish communiTy | disTribuTed To over 100,000 people in 18,000 homes, shuls & sTores Vol. 1 N0. 26 November 4, 2010 | ,ag”t jaui fwwz A Citicom! Publication INSIDE FJJ FJJ CoMMuNITY BuLLETIN An observant Eye 60 Flatbush Political Landscape Business Directory 61 Unchanged By Election Children's Page 64 Dov Hikind prevailed while in nered just under 8 percent of the Flatbush Focus 50 the state Senate Kevin Parker and vote. Flatbush Freilich 50 Carl Kruger secured new two- Mr. Weiner won by a com- Flatbush Shomrim year terms. U.S. Representatives fortable margin, but the tight- Flatbush Weather 4 Anthony Weiner, Yvette Clarke est of any New York member of Warns Community and Ed Towns, all of whom have the House, 58-41 percent against Flatbush Zmanim 3 THIS SUNDAY Gambling Parlors Avi Hartstein a slice of Flatbush in their dis- well-funded challenger Bob gemach Directory 43 Th e momentous election that tricts, will return to Capitol Hill Turner, a former broadcasting Even before the sinking in the next Congress. executive. Towns won 90 percent Halachically Speaking 29 swept change across the country, economy and high unemploy- shift ing the House of Represen-See our ad onMr. page Hikind won 68 percent of of the vote against Diana Mu- ment rate, there were those Health & Fitness 54 tatives from Democrat to Repub- the vote, warding off his fi rst ma- niz and Clarke won 90 percent who took on gambling as their jor challenge in years from Brian against Hugh Carr. -

Spotlight Issue in Order to Avoid a GADOL in the Grammar Mistakes

ש ב ת פ ר ש ת א מ ו ר M A Y 1 , 2 0 2 1 י ט ׳ א י י ר ת ש פ ״ א A DACHS STUDENT WEEKLY NEWSLETTER What's Inside D'VAR TORAH By Rabbi Yitzchok Schlissel - 11th Grade Rebbi; S'gan D'VAR T ORAH Menahel, Honors Track Each week, we try to look over the Spotlight issue in order to avoid A GADOL IN THE grammar mistakes. This is because we understand the importance of using proper grammar and speaking correctly. Yet there is SPOTLIGHT seemingly a blatant grammar mistake in this week's Parshah. שור או כשב" ,When describing the young animals brought as korbanos, the Torah says is an adult animal. The correct word for a baby שור The problem is that a ."או עז כי יוולד D'VAR HALACHA כלל addresses this issue in an incredible way. Because מדרש The !"עגל" cow would be Hashem did not want to mention that word, which ,עגל had sinned with the ישראל of their sin, so He used a different word כלל ישראל PARSHA TEASER would highlight and perhaps remind instead. THIS WEEK IN .point out what a lesson Hashem is teaching us. Yes, the people sinned בעלי מוסר The PICTURES Yes, they deserved to be punished. Yet, nevertheless, they are people and need to be NEW NIGHT treated with respect, in a manner that preserves their self-respect and that does not SEDER PROGRAM shame them. And it is even worthwhile for Hashem to "go out of His way" to write an In fact, it .צלם אלקים imprecise" word in the Torah in order to preserve the dignity of a" WEEKLY is not an imprecise word, but is rather perfectly precise - a precise grammar mistake to PUZZLER teach a fundamental lesson in how to treat others, even if they may have done wrong. -

LEGACY JUDAICA May 30Th 2021

LEGACY JUDAICA May 30th 2021 AUCTION OF FINE ANTIQUE JUDAICA Sunday May 30th 2021 1:00 pm Estreia 978 River Ave, Lakewood, N.J. 08701 PRE AUCTION VIEWING: Tuesday May 25th in Lakewood NJ by appointment Wednesday May 26th in Lakewood NJ by appointment Thursday May 27th in Lakewood NJ by appointment ONLINE BIDDING AT: http://legacyjudaica.bidspirit.com LEGACY JUDAICA Tel: 732.523.2262 Fax: 732.523.2191 Email: [email protected] legacyjudaica.net נבלי וכנורי בפי עטי גני ופרדסי ספריה ר׳ יהודה הלוי “My lyre and my harp are the u t t e r a n c e s o f m y q u i l l , M y g a r d e n and my orchard are it’s literature” R. Yehuda Halevi LEGACY JUDAICA LEGACY JUDAICA Yehuda A. Schwarz SEFORIM AND MANUSCRIPTS Feivel Schneider EDITOR IN CHIEF N. Ben-Moshe RABBINIC RESEARCH Rabbi Moshe Maimon HEBREW TRANSCRIPTS Rabbi Shlome Meir Pashkus HEBREW TEXT Shoshana Visky GRAPHICS AND DESIGN Sara Hager WEBSITE ADMINISTRATOR Shloime Breuer - Tech Design Shoshana Meyer mbtechdesign.com IMAGING AND PHOTOGRAPHY Moshe Cweiber CONTENTS EARLY PRINTED SEFORIM ספרים מודפסים קדומים 6 PRINTED SEFORIM ספרים מודפסים 30 MANUSCRIPTS OF SEFORIM כתבי יד של ספרים 54 POLEMICS פולמוסים 57 SIFREI CHASSIDUS AND KABBALAH ספרי קבלה/חסידות 65 SIFREI SLAVITTA AND ZHITOMIR ספרי סלאוויטא/ז׳יטומיר 73 SIFREI HA'GRA ספרי הגר׳׳א 78 HOLOCAUST שואה 85 SEFORIM WITH SIGNATURES/GLOSSES ספרים עם חתימות/ הערות 86 RABBINICAL LETTERS/MANUSCRIPTS מכתבים מרבנים וכתבי יד 100 Early Printed Seforim ספרים מודפסים קדומים ספרי יסוד. עמודי גולה סמ׳׳ק. -

Download (PDF, 4.67MB)

T 1--1 E J E W I S 1-1 OBSERVER ······ 1 ' ' ' THE I , ,- ,, ' / .' It' i 'I ewts.···, IN THIS ISSUE 1 :BSEltvE.R SHARING THE BURDENS OF OUR FELLOWS THE JEWISH OBSERVER 7 SAVING KLAL YrsROEL W1TH CHESSED, {ISSN) 002.1-6615 IS Pl!llUSBt:O MONl'Hl.Y, EXCEPT JlJl.Y & AUGUSl Rabbi Aryeh Zev Ginzberg AND A COMBINED JSSUI' FOR JANUA£1YiFEJHHJARY. BY HIE 10 THE AWESOME POWER OF HAMISPAl.E!L AGUDATH !SRAEL or AMHUCA. 42 BHOADWAY. NEW YOllK, NY 10004. BEfAD CHAVEIRO, l'ERIODICAl.S POSTA{;E PAID IN NEW Rabbi /-leshy K/einrnan YOllK, NY. SUBSCRIPTION S25.oo/ Yl-:AR; 2 Y!'.ARS. $48.00; 3 YEAllS. S69.00. Ou-rs1or-: Of THE UNITED 16 DIMENSIONS OF AN AMEil BATORAH: STATES (l'S HINDS DRAWN ON A \JS RABBI SHMUEL BERENBAUM,?'·::-Ir, BANK ONLY) S15.oo SllRCMAHt;E !'ER YEAR. SINGLE COPY $3.50; OursJDE Rabbi Shirnon Finkelman N)' AREA S:;.95; FOIH:H;N $4.50. 42 THE CLUTTERED NEST POSTMASTER: tvlarsha on1acw•1 SF:ND ADURf.SS CH,\NGES TO; TEL 212-797-9000, FAX 646-254• 1600 PIUNTED IN THE USA LETTER FROM JERUSALEM RAUH! NtSSON WO!.PJN, Fditor 19 SOME LESS OBVIOUS LESSONS Fd1toriol Jiourd fRQf\/I THE MAYORAL ELECTION, RABBI AOBA 8RUDNY RAllBI JOSE!'!! EU.AS Yonoson Rosenb!urn JOSEPH fRIEl)ENSON RABBI YISROEL MElll KllO".NEH R·\Hf:ll NosSON SCIH·:RMAN PROF. /\1\RON TWERSKI HIGHER LIGHTS OF CHANUKAH /"i)(fndcrs DR. ERNST I.. BODENHEIMER Z"L 23 THE CANDLES AND THE STARS, RA!lBI MOSHE SHJCRER Z"J. -

E 6Rowing Jewish Community

It costs nothing to ensure your child has the best of everything. ALL PROGRAMS ARE PERFORMED AT CLIENT'S At Amerlklds, our early intervention programs are more than HOME, FREE OF CHARGE AND INCLUDE: just among the best available in the state, they're also free. Im CORE & SUPPLEMENTAL EVALUATIONS That means you get the level of professionalism - and performance that only one of the state's top healthcare l!l!l SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY providers can deliver, and you get it with no out of pocket costtoyou. Iii! PHYSICAL & OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY Think about it, a program custom tailored to the unique Im FAMILY ANO/OR NUTRITIONAL TRAINING & COUNSEUNG needs of your child and implemented with an eye towards your child's future - all delivered in the comfort of your own !Ml SOCIAL WORK home ... and all for free. And because we're part of the Americare Family of Companies - a company with over two R SPECIAL INSTRUCTION decades of experience as a leader in healthcare services, you Iii NURSING know your child is getting the absolute best care possible. If your child is between newborn and age three, and llli Bl~LJNGUAL THERAPISTS (YIDDISH, needs help with talking, walking, feeding, paying attention RUSSIAN, HEBREW AND OTHER LANGUAGES} or getting along with others, you may be eligible for our free Early Intervention Program. Ii THE PEACE OF MIND THAT COMES FROM WORKING WITH SHOMER SHABBOS, WARM AND CARING THERAPISTS Call us today to give your child the best of everything ... AND PROFESSIONALS today and tomorrow. EARLY INTERVENTION PROGRAM 718·434-3600 ext. -

Reading Medieval Religious Disputation: the 1240 “Debate” Between Rabbi Yeḥiel of Paris and Friar Nicholas Donin

Reading Medieval Religious Disputation: The 1240 “Debate” Between Rabbi Yeḥiel of Paris and Friar Nicholas Donin by Saadia R. Eisenberg A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes, Co-Chair Associate Professor Stefanie B. Siegmund, Co-Chair Associate Professor Yaron Z. Eliav Associate Professor Helmet Puff “The normal historical approach is to compare differing versions of the same set of events in order to elicit a core of irrefutable fact. The text is thereby regarded as a source of information. However, the accounts are also works of narrative art. In this capacity they operate on two levels: they tell us about the narrator’s point of view, and, if a movement is recorded in more than one place, they paint different pictures of how the individuals activating it looked upon each other...” (89) Brian Stock, The Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretations in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Princeton: University Press, 1982) 89. © Saadia R. Eisenberg 2008 For my parents ii Acknowledgements One of the most gratifying aspects of completing my dissertation is the ability to thank and recognize those who have helped me along the way. I could not have completed the research or the writing for this project without the strong foundation of support provided by the collective commitments of great research institutions, funding, mentors, scholars, and family. This dissertation studies the religious and intellectual history of medieval Latin Christendom and of the medieval Jewish experience, and because of this I have benefited from the assistance of numerous scholars across a variety of disciplines. -

PIRCHEI Agudas Yisroel of America Vol: 3 Issue: 11 - כ"ח טבת, תשע"ו - January 9, 2016 פרשה: וארא - הפטרה: הפטרה: ...בקבצי את בית ישראל

בס״ד PIRCHEI Agudas Yisroel of America Vol: 3 Issue: 11 - כ"ח טבת, תשע"ו - January 9, 2016 פרשה: וארא - הפטרה: הפטרה: ...בקבצי את בית ישראל... )יחזקאל כח:כה-כט:כא( דף יומי: גיטין כ״ז מברכים ר״ח שבט ]יום שני[ )מולד מוצאי שבת קודש בשעה: חלקים 13 + 20:03( TorahThoughts .s glory to the world’ד׳ reveal רְ ע שָ ִּ י ם and the צַּ דִּ י קִּ י ם Both the … בַּעֲבוּרזֺאת הֶ עֱמַּדְתִּ יָך בַּעֲבוּר הַּרְ אֺתְ ָך אֶ ת־כֺחִּ י וּלְמַּ עַּןסַּ פֵּר שְמִּ י בְ כָל־הָ אָרֶ ץ which מַּ עֲשִּ ים טוֹבִּ ים and מִּ צְ וֹ ת accomplish this through their צַּ דִּ י קִּ י ם The )שְ מוֹת ט:טז(. accomplish it in a רְ ע שָ ִּ י ם in the world, while the כְב דוֹ שָ מַּ יִּ ם for this I have let you survive, so that you may behold My increase … strength and declare [the greatness of] My Name throughout the land. different way. They are similar to the “wood for building and heat.” ֺ to include Their destruction also glorifies His Name. Throughout history theמ שֶ ה commanded ד׳ , ָ ב רָ ד Before the plague of adding seemingly invincible wicked empires have perished, in fulfillment of ד׳ What was . פַּ רְ ֺע ה these few additional words in his warning to when , בִּפְ ר ֺ חַּ רְ שָ עִּ י ם … עֵּשֶב, וַּיָצִּיצוּכָל פֺעֲלֵּי אָוֶן, לְהִּשָמְדָםעֲדֵּי עַּד to remain the verse פַּ רְ ֺע ה wanted ד׳ with these words? Does this really mean that alive just so he should declare His Glory? It is possible that this was for the wicked bloom like grass and all the doers of iniquity blossom — it is צַּדִּיק כַּתָמָר ,In contrast .( תְ ל הִּ ִּ י ם צ ב : ח) being forced for the -

Sephardic News in Dedication to a Heritage Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Sephardic Council of Overseers

YESHIVA UNIVERSITY SEPHARDIC NEWS IN DEDICATION TO A HERITAGE RABBI ISAAC ELCHANAN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY SEPHARDIC COUNCIL OF OVERSEERS VOLUME XXXVIII I NO. 1 I FALL 2018 – SPRING 2019 / 5778 – 5779 New YU President Rabbi Ari Berman Meets Sephardic Leaders The SCO is a lay leadership council under the aegis of YU’s Sephardic Community Programs and includes representatives from the Syrian, Persian, Iraqi, Moroccan, Judeo-Spanish, Spanish-Portuguese, Bukharain, Yemenite, and other Middle Eastern communities who 5 are active in their respective com- munities in leadership roles in the gathered group of leaders. Rabbi Yeshiva to serving the Sephardic various synagogues and Jewish day Berman talked warmly and world at large, and the Sephardic 1 schools throughout the Sephardic engagingly about the Sephardic campus community, which is enclaves of NY and NJ. students on campus. He also fielded literally a parallel microcosm of the Rabbi Dr. Herbert C. Dobrinsky, During the spring 2018 semester, questions and comments from the Sephardic population throughout Vice President for University YU President Rabbi Dr. Ari Berman group regarding his vision for YU the world. Affairs and co-founder of Yeshiva’s met Sephardic lay leaders at an as he takes the helm of Yeshiva’s Dr. Dobrinsky as well as Rabbi ,ucuyu ,unhgb ,ucr ohbak ufz, Sephardic Programs in 1964, evening event hosted by the leadership into the next exciting Berman and Rabbi Tessone all May you merit many years in good health and happiness. introduced Rabbi Berman before Sephardic Council of Overseers era in YU’s growth. expressed their excitement at the his keynote presentation to the (SCO) at YU’s Beren Campus. -

Entire Issue to One Subject

i"O:J. COMPREHENSIVE OUTREACH,. ® Kindergarten - 12th Grade Parenting Workshops Counseling to Yeshiva and Day School Students Identified as At-Risk On Site Consultation & Staff Development for Yeshivas Available at No Charge to Yeshivas and Families in New York City For more information, call 718-339-3379 ext 210 1960 SCHENECTADY AVENUE TEL. 718-252-0801 BROOKLYN, NY 11234 FAX. 718-252-6787 TIFERES ACADE Y BOYS YESHIVA HIGH SCHOOL IT IS OUR MISSION TO DEDICATE OURSELVES TO ANY i1n:J WHO IS WILLING TO CONFORM TO THE TIFERES OPPORTUNITY. Tiferes Academy has an unparalleled staff that brings out the po,tefh: ··· +f<;:- 'Sl1J&' \~?, - every iin:i. Our innovative and creative program provides t~.@1•:·fle~l6lllty and individuality for those bochurim who need a second '"cfi~~~Ji• Y~ur call to Tiferes Academy might be your best call yet. ··;~,''•'"' FEATURING: • One-on-One Kolle! Cllavrusah Progr Academic Regents Diploma • Mishmor Prr;ac>i11 • Daily Supervised Gym & Swim • Shabbatonim • Full Computer activities • Professional Writing Clinic • Professional • Master Dedicated Rabbei111 • Hatzalah, Aid, courses We also offer high school & bais midrash placement services! DYNAMIC FACULTY: Rabbi Moshe Aronov Rabbi Chaim Pechter Rabbi I Dr. Avrohom Pinter Principal, #;g~ew Studies Menahef Ruchni Principal, General Studies We are privileged to have Rabbi Chaim Pechter, shlita, a renowned maggid shiur at Yeshiva Tiferes Torah, who in addition to those duties, will act as menahel ruchni at our high school. His many years of experience in chinuch excellence are sure to add much to our Institution. Vaad Hachlnuch: Harav Shmuel Berenbaum, Harav Yitzchok Feigelstock, Harav Mordechai Gifter, Harav Shmuel Kamenetzky, Harav Avrohom Pam, Harav Aharon Moshe Schechter, Harav Yaakov Schneidman Horav Elya Svei, Yoshev Rosh Become a member of the Chofetz Chaim Heritage Foundation and help eradicate the primary causes of the destruction of the Bais Hamikdash - loshon hora and sinas chinom.