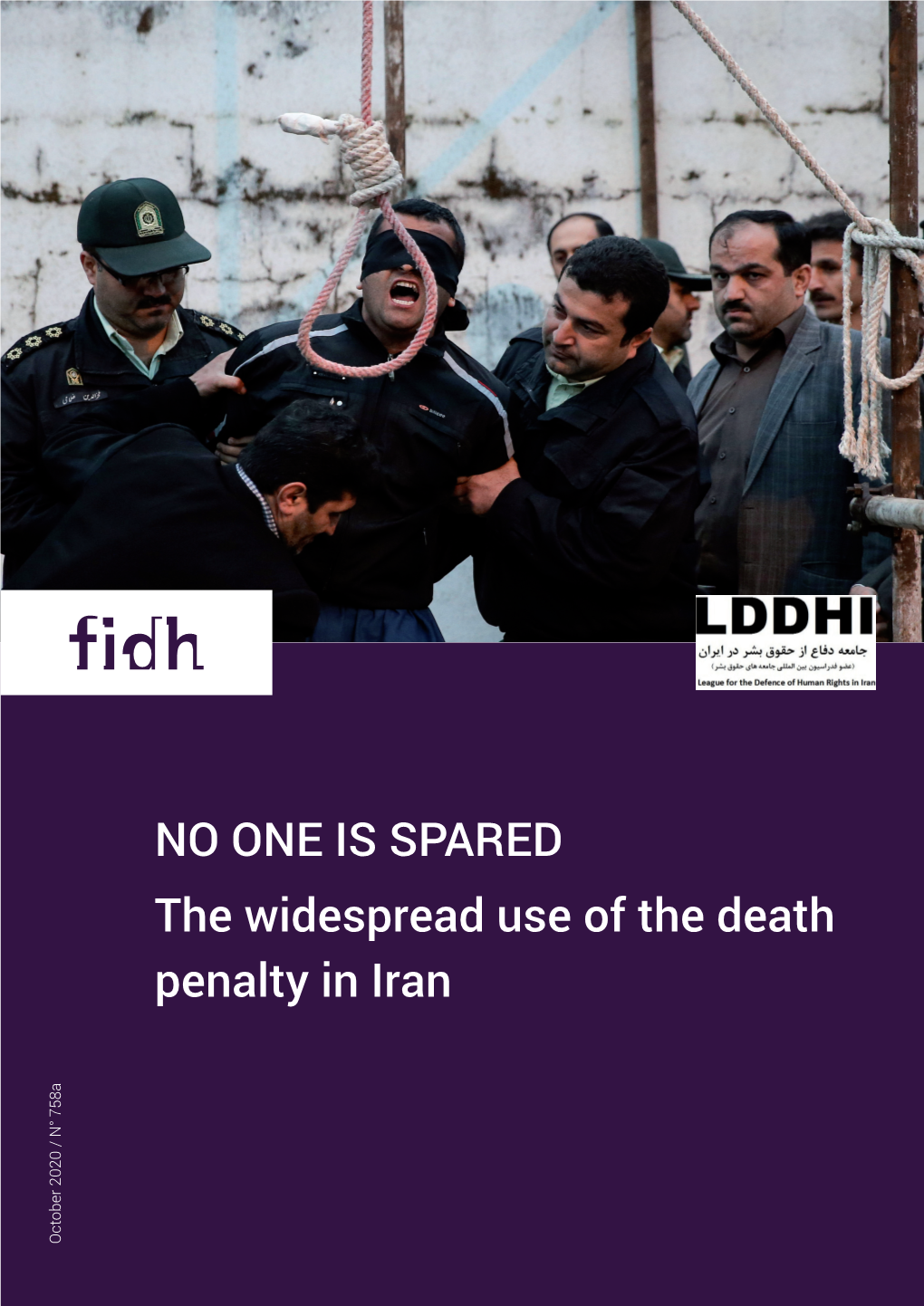

NO ONE IS SPARED the Widespread Use of the Death Penalty in Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iran Human Rights Defenders Report 2019/20

IRAN HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS REPORT 2019/20 Table of Contents Definition of terms and concepts 4 Introduction 7 LAWYERS Amirsalar Davoudi 9 Payam Derafshan 10 Mohammad Najafi 11 Nasrin Sotoudeh 12 CIVIL ACTIVISTS Zartosht Ahmadi-Ragheb 13 Rezvaneh Ahmad-Khanbeigi 14 Shahnaz Akmali 15 Atena Daemi 16 Golrokh Ebrahimi-Irayi 17 Farhad Meysami 18 Narges Mohammadi 19 Mohammad Nourizad 20 Arsham Rezaii 21 Arash Sadeghi 22 Saeed Shirzad 23 Imam Ali Popular Student Relief Society 24 TEACHERS Esmaeil Abdi 26 Mahmoud Beheshti-Langroudi 27 Mohammad Habibi 28 MINORITY RIGHTS ACTIVISTS Mary Mohammadi 29 Zara Mohammadi 30 ENVIRONMENTAL ACTIVISTS Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation 31 Workers rights ACTIVISTS Marzieh Amiri 32 This report has been prepared by Iran Human Rights (IHR) Esmaeil Bakhshi 33 Sepideh Gholiyan 34 Leila Hosseinzadeh 35 IHR is an independent non-partisan NGO based in Norway. Abolition of the Nasrin Javadi 36 death penalty, supporting human rights defenders and promoting the rule of law Asal Mohammadi 37 constitute the core of IHR’s activities. Neda Naji 38 Atefeh Rangriz 39 Design and layout: L Tarighi Hassan Saeedi 40 © Iran Human Rights, 2020 Rasoul Taleb-Moghaddam 41 WOMEN’S RIGHTS ACTIVISTS Raha Ahmadi 42 Raheleh Ahmadi 43 Monireh Arabshahi 44 Yasaman Aryani 45 Mojgan Keshavarz 46 Saba Kordafshari 47 Nedaye Zanan Iran 48 www.iranhr.net Recommendations 49 Endnotes 50 : @IHRights | : @iranhumanrights | : @humanrightsiran Definition of Terms & Concepts PRISONS Evin Prison: Iran’s most notorious prison where Wards 209, 240 and 241, which have solitary cells called security“suites” and are controlled by the Ministry of Intelligence (MOIS): Ward 209 Evin: dedicated to security prisoners under the jurisdiction of the MOIS. -

The Combined Use of Long-Term Multi-Sensor Insar Analysis and Finite Element Simulation to Predict Land Subsidence

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-4/W18, 2019 GeoSpatial Conference 2019 – Joint Conferences of SMPR and GI Research, 12–14 October 2019, Karaj, Iran THE COMBINED USE OF LONG-TERM MULTI-SENSOR INSAR ANALYSIS AND FINITE ELEMENT SIMULATION TO PREDICT LAND SUBSIDENCE M. Gharehdaghi 1,*, A. Fakher 2, A. Cheshomi 3 1 MSc. Student, School of Civil Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran – [email protected] 2 Civil Engineering Department, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran – [email protected] 3 Department of Engineering Geology, School of Geology, College of Science, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran - [email protected] KEY WORDS: Land Subsidence, Ground water depletion, InSAR data, Numerical Simulation, Finite Element Method, Plaxis 2D, Tehran ABSTRACT: Land subsidence in Tehran Plain, Iran, for the period of 2003-2017 was measured using an InSAR time series investigation of surface displacements. In the presented study, land subsidence in the southwest of Tehran is characterized using InSAR data and numerical modelling, and the trend is predicted through future years. Over extraction of groundwater is the most common reason for the land subsidence which may cause devastating consequences for structures and infrastructures such as demolition of agricultural lands, damage from a differential settlement, flooding, or ground fractures. The environmental and economic impacts of land subsidence emphasize the importance of modelling and prediction of the trend of it in order to conduct crisis management plans to prevent its deleterious effects. In this study, land subsidence caused by the withdrawal of groundwater is modelled using finite element method software Plaxis 2D. -

Civil Courage Newsletter

Civil Courag e News Journal of the Civil Courage Prize Vol. 11, No. 2 • September 2015 For Steadfast Resistance to Evil at Great Personal Risk Bloomberg Editor-in-Chief John Guatemalans Claudia Paz y Paz and Yassmin Micklethwait to Deliver Keynote Barrios Win 2015 Civil Courage Prize Speech at the Ceremony for Their Pursuit of Justice and Human Rights ohn Micklethwait, Bloomberg’s his year’s recipients of the JEditor-in-Chief, oversees editorial TCivil Courage Prize, Dr. content across all platforms, including Claudia Paz y Paz and Judge Yassmin news, newsletters, Barrios, are extraordinary women magazines, opinion, who have taken great risks to stand television, radio and up to corruption and injustice in digital properties, as their native Guatemala. well as research ser- For over 18 years, Dr. Paz y Paz vices such as has been dedicated to improving her Claudia Paz y Paz Bloomberg Intelli - country’s human rights policies. She testing, wiretaps and other technol - gence. was the national consultant to the ogy, she achieved unprecedented re - Prior to joining UN mission in Guatemala and sults in sentences for homicide, rape, Bloomberg in February 2015, Mickle- served as a legal advisor to the violence against women, extortion thwait was Editor-in-Chief of The Econo - Human Rights Office of the Arch - and kidnapping. mist, where he led the publication into the bishop. In 1994, she founded the In - In a country where witnesses, digital age, while expanding readership stitute for Com- prosecutors, and and enhancing its reputation. parative Criminal judges were threat - He joined The Economist in 1987, as Studies of Guate- ened and killed, she a finance correspondent and served as mala, a human courageously Business Editor and United States Editor rights organization sought justice for before being named Editor-in-Chief in that promotes the victims of the 2006. -

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY the Islamic Republic of Iran

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is a constitutional, theocratic republic in which Shia Muslim clergy and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate the key power structures. Government legitimacy is based on the twin pillars of popular sovereignty--albeit restricted--and the rule of the supreme leader of the Islamic Revolution. The current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was chosen by a directly elected body of religious leaders, the Assembly of Experts, in 1989. Khamenei’s writ dominates the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government. He directly controls the armed forces and indirectly controls internal security forces, the judiciary, and other key institutions. The legislative branch is the popularly elected 290-seat Islamic Consultative Assembly, or Majlis. The unelected 12-member Guardian Council reviews all legislation the Majlis passes to ensure adherence to Islamic and constitutional principles; it also screens presidential and Majlis candidates for eligibility. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was reelected president in June 2009 in a multiparty election that was generally considered neither free nor fair. There were numerous instances in which elements of the security forces acted independently of civilian control. Demonstrations by opposition groups, university students, and others increased during the first few months of the year, inspired in part by events of the Arab Spring. In February hundreds of protesters throughout the country staged rallies to show solidarity with protesters in Tunisia and Egypt. The government responded harshly to protesters and critics, arresting, torturing, and prosecuting them for their dissent. As part of its crackdown, the government increased its oppression of media and the arts, arresting and imprisoning dozens of journalists, bloggers, poets, actors, filmmakers, and artists throughout the year. -

Prepared Testimony to the United States Senate Foreign Relations

Prepared Testimony to the United States Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Near Eastern and South and Central Asian Affairs May 11, 2011 HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATIC REFORM IN IRAN Andrew Apostolou, Freedom House Chairman Casey, Ranking member Risch, Members of the Subcommittee, it is an honour to be invited to address you and to represent Freedom House. Please allow me to thank you and your staff for all your efforts to advance the cause of human rights and democracy in Iran. It is also a great pleasure to be here with Rudi Bakhtiar and Kambiz Hosseini. They are leaders in how we communicate the human rights issue, both to Iran and to the rest of the world. Freedom House is celebrating its 70th anniversary. We were founded on the eve of the United States‟ entry into World War II by Eleanor Roosevelt and Wendell Wilkie to act as an ideological counterweight to the Nazi‟s anti-democratic ideology. The Nazi headquarters in Munich was known as the Braunes Haus, so Roosevelt and Wilkie founded Freedom House in response. The ruins of the Braunes Haus are now a memorial. Freedom House is actively promoting democracy and freedom around the world. The Second World War context of our foundation is relevant to our Iran work. The Iranian state despises liberal democracy, routinely violates human rights norms through its domestic repression, mocks and denies the Holocaust. Given the threat that the Iranian state poses to its own population and to the Middle East, we regard Iran as an institutional priority. In addition to Freedom House‟s well-known analyses on the state of freedom in the world and our advocacy for democracy, we support democratic activists in some of the world‟s most repressive societies, including Iran. -

IRAN COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

IRAN COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 28 June 2011 IRAN JUNE 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN IRAN FROM 14 MAY TO 21 JUNE Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON IRAN PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 14 MAY AND 21 JUNE Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Maps ...................................................................................................................... 1.04 Iran ..................................................................................................................... 1.04 Tehran ................................................................................................................ 1.05 Calendar ................................................................................................................ 1.06 Public holidays ................................................................................................... 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Pre 1979: Rule of the Shah .................................................................................. 3.01 From 1979 to 1999: Islamic Revolution to first local government elections ... 3.04 From 2000 to 2008: Parliamentary elections -

Blood-Soaked Secrets Why Iran’S 1988 Prison Massacres Are Ongoing Crimes Against Humanity

BLOOD-SOAKED SECRETS WHY IRAN’S 1988 PRISON MASSACRES ARE ONGOING CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Cover photo: Collage of some of the victims of the mass prisoner killings of 1988 in Iran. Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons © Amnesty International (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 13/9421/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS GLOSSARY 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 METHODOLOGY 18 2.1 FRAMEWORK AND SCOPE 18 2.2 RESEARCH METHODS 18 2.2.1 TESTIMONIES 20 2.2.2 DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE 22 2.2.3 AUDIOVISUAL EVIDENCE 23 2.2.4 COMMUNICATION WITH IRANIAN AUTHORITIES 24 2.3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 25 BACKGROUND 26 3.1 PRE-REVOLUTION REPRESSION 26 3.2 POST-REVOLUTION REPRESSION 27 3.3 IRAN-IRAQ WAR 33 3.4 POLITICAL OPPOSITION GROUPS 33 3.4.1 PEOPLE’S MOJAHEDIN ORGANIZATION OF IRAN 33 3.4.2 FADAIYAN 34 3.4.3 TUDEH PARTY 35 3.4.4 KURDISH DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF IRAN 35 3.4.5 KOMALA 35 3.4.6 OTHER GROUPS 36 4. -

PROTESTS and REGIME SUPPRESSION in POST-REVOLUTIONARY IRAN Saeid Golkar

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY n OCTOBER 2020 n PN85 PROTESTS AND REGIME SUPPRESSION IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY IRAN Saeid Golkar Green Movement members tangle with Basij and police forces, 2009. he nationwide protests that engulfed Iran in late 2019 were ostensibly a response to a 50 percent gasoline price hike enacted by the administration of President Hassan Rouhani.1 But in little time, complaints Textended to a broader critique of the leadership. Moreover, beyond the specific reasons for the protests, they appeared to reveal a deeper reality about Iran, both before and since the 1979 emergence of the Islamic Republic: its character as an inherently “revolutionary country” and a “movement society.”2 Since its formation, the Islamic Republic has seen multiple cycles of protest and revolt, ranging from ethnic movements in the early 1980s to urban riots in the early 1990s, student unrest spanning 1999–2003, the Green Movement response to the 2009 election, and upheaval in December 2017–January 2018. The last of these instances, like the current round, began with a focus on economic dissatisfaction and then spread to broader issues. All these movements were put down by the regime with characteristic brutality. © 2020 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. SAEID GOLKAR In tracking and comparing protest dynamics and market deregulation, currency devaluation, and the regime responses since 1979, this study reveals that cutting of subsidies. These policies, however, spurred unrest has become more significant in scale, as well massive inflation, greater inequality, and a spate of as more secularized and violent. -

Search Results

Showing results for I.N. BUDIARTA RM, Risks management on building projects in Bali Search instead for I.N. BUDIARTHA RM, Risks management on building projects in Bali Search Results Volume 7, Number 2, March - acoreanajr.com www.acoreanajr.com/index.php/archive?layout=edit&id=98 Municipal waste cycle management a case study: Robat Karim County .... I.N. Budiartha R.M. Risks management on building projects in Bali Items where Author is "Dr. Ir. Nyoman Budiartha RM., MSc, I NYOMAN ... erepo.unud.ac.id/.../Dr=2E_Ir=2E__Nyoman_Budiart... Translate this page Jul 19, 2016 - Dr. Ir. Nyoman Budiartha RM., MSc, I NYOMAN BUDIARTHA RM. (2015) Risks Management on Building Projects in Bali. International Journal ... Risks Management on Building Projects in Bali - UNUD | Universitas ... https://www.unud.ac.id/.../jurnal201605290022382.ht... Translate this page May 29, 2016 - Risks Management on Building Projects in Bali. Abstrak. Oleh : Dr. Ir. Nyoman Budiartha RM., MSc. Email : [email protected]. Kata kunci ... [PDF]Risk Management Practices in a Construction Project - ResearchGate https://www.researchgate.net/file.PostFileLoader.html?id... ResearchGate 5.1 How are risks and risk management perceived in a construction project? 50 ... Risk management (RM) is a concept which is used in all industries, from IT ..... structure is easy to build and what effect will it have on schedule, budget or safety. Missing: budiarta bali [PDF]Risk management in small construction projects - Pure https://pure.ltu.se/.../LTU_LIC_0657_SE... Luleå University of Technology by K Simu - Cited by 24 - Related articles The research school Competitive Building has also been invaluable for my work .... and obstacles for risk management in small projects are also focused upon. -

Iran 2019 Human Rights Report

IRAN 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is an authoritarian theocratic republic with a Shia Islamic political system based on velayat-e faqih (guardianship of the jurist). Shia clergy, most notably the rahbar (supreme leader), and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate key power structures. The supreme leader is the head of state. The members of the Assembly of Experts are nominally directly elected in popular elections. The assembly selects and may dismiss the supreme leader. The candidates for the Assembly of Experts, however, are vetted by the Guardian Council (see below) and are therefore selected indirectly by the supreme leader himself. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has held the position since 1989. He has direct or indirect control over the legislative and executive branches of government through unelected councils under his authority. The supreme leader holds constitutional authority over the judiciary, government-run media, and other key institutions. While mechanisms for popular election exist for the president, who is head of government, and for the Islamic Consultative Assembly (parliament or majles), the unelected Guardian Council vets candidates, routinely disqualifying them based on political or other considerations, and controls the election process. The supreme leader appoints half of the 12-member Guardian Council, while the head of the judiciary (who is appointed by the supreme leader) appoints the other half. Parliamentary elections held in 2016 and presidential elections held in 2017 were not considered free and fair. The supreme leader holds ultimate authority over all security agencies. Several agencies share responsibility for law enforcement and maintaining order, including the Ministry of Intelligence and Security and law enforcement forces under the Interior Ministry, which report to the president, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which reports directly to the supreme leader. -

Opinions Adopted by the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention at Its Eighty-Fifth Session, 12–16 August 2019

A/HRC/WGAD/2019/33 Advance Edited Version Distr.: General 9 September 2019 Original: English Human Rights Council Working Group on Arbitrary Detention Opinions adopted by the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention at its eighty-fifth session, 12–16 August 2019 Opinion No. 33/2019 concerning Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee (Islamic Republic of Iran) 1. The Working Group on Arbitrary Detention was established in resolution 1991/42 of the Commission on Human Rights. In its resolution 1997/50, the Commission extended and clarified the mandate of the Working Group. Pursuant to General Assembly resolution 60/251 and Human Rights Council decision 1/102, the Council assumed the mandate of the Commission. The Council most recently extended the mandate of the Working Group for a three-year period in its resolution 33/30. 2. In accordance with its methods of work (A/HRC/36/38), on 29 March 2019, the Working Group transmitted to the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran a communication concerning Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee. The Government replied to the communication on 24 June 2019. The Islamic Republic of Iran is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. 3. The Working Group regards deprivation of liberty as arbitrary in the following cases: (a) When it is clearly impossible to invoke any legal basis justifying the deprivation of liberty (as when a person is kept in detention after the completion of his or her sentence or despite an amnesty law applicable to him or her) (category I); (b) When the deprivation of liberty results -

Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ahmed Shaheed*,**

A/HRC/28/70 Advance Unedited Version Distr.: General 12 March 2015 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-eighth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ahmed Shaheed*,** Summary In the present report, the fourth to be submitted to the Human Rights Council pursuant to Council resolution 25/24, the Special Rapporteur highlights developments in the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran since his fourth interim report submitted to the General Assembly (A/68/503) in October 2013. The report examines ongoing concerns and emerging developments in the State’s human rights situation. Although the report is not exhaustive, it provides a picture of the prevailing situation as observed in the reports submitted to and examined by the Special Rapporteur. In particular, and in view of the forthcoming adoption of the second Universal Periodic Review of the Islamic Republic of Iran, it analysis these in light of the recommendations made during the UPR process. * Late submission. ** The annexes to the present report are circulated as received, in the language of submission only. GE.15- A/HRC/28/70 Contents Paragraphs Page I. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1-5 3 II. Methodology ........................................................................................................... 6-7 4 III. Cooperation