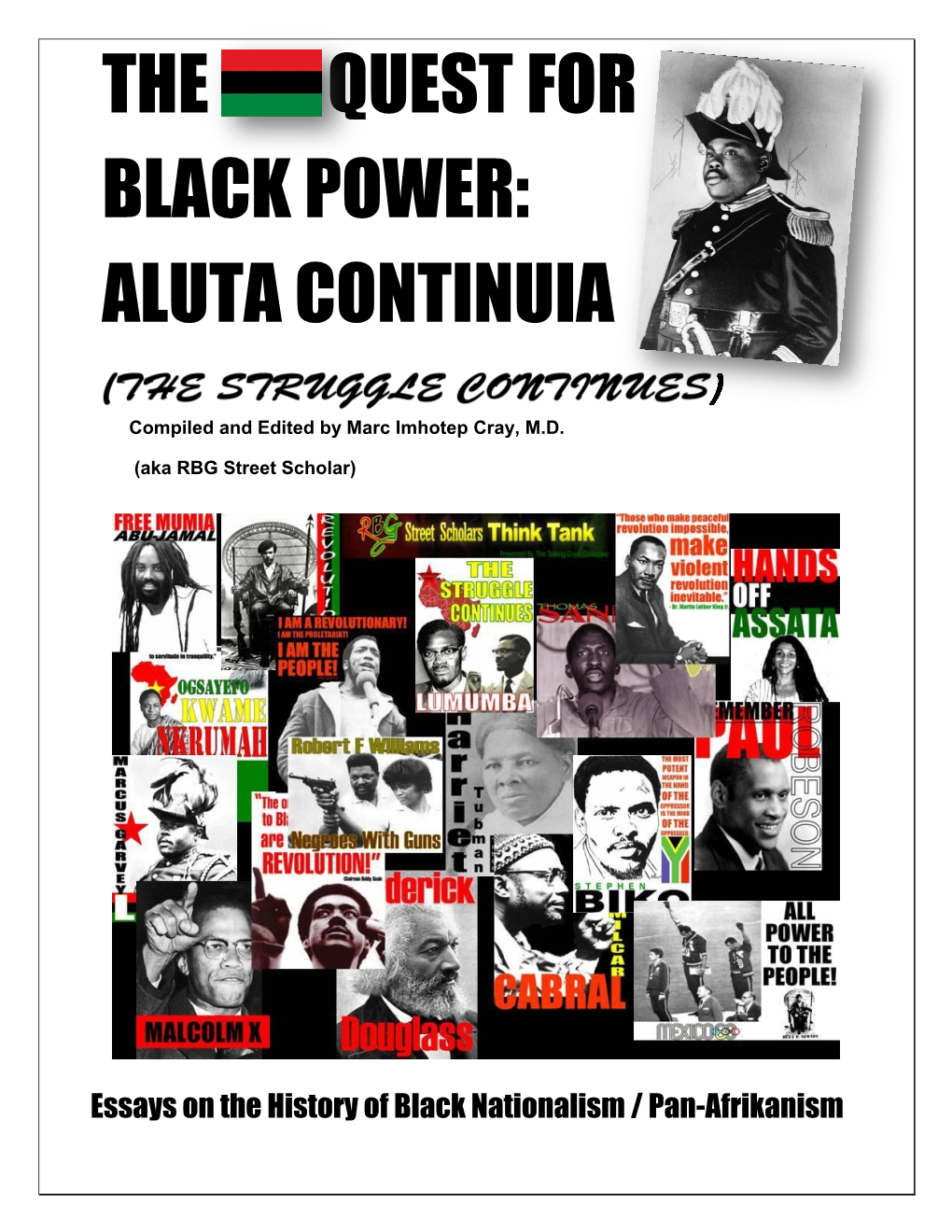

The Quest for Black Power: Aluta Continuia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

Williams, Hipness, Hybridity, and Neo-Bohemian Hip-Hop

HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Maxwell Lewis Williams August 2020 © 2020 Maxwell Lewis Williams HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Maxwell Lewis Williams Cornell University 2020 This dissertation theorizes a contemporary hip-hop genre that I call “neo-bohemian,” typified by rapper Kendrick Lamar and his collective, Black Hippy. I argue that, by reclaiming the origins of hipness as a set of hybridizing Black cultural responses to the experience of modernity, neo- bohemian rappers imagine and live out liberating ways of being beyond the West’s objectification and dehumanization of Blackness. In turn, I situate neo-bohemian hip-hop within a history of Black musical expression in the United States, Senegal, Mali, and South Africa to locate an “aesthetics of existence” in the African diaspora. By centering this aesthetics as a unifying component of these musical practices, I challenge top-down models of essential diasporic interconnection. Instead, I present diaspora as emerging primarily through comparable responses to experiences of paradigmatic racial violence, through which to imagine radical alternatives to our anti-Black global society. Overall, by rethinking the heuristic value of hipness as a musical and lived Black aesthetic, the project develops an innovative method for connecting the aesthetic and the social in music studies and Black studies, while offering original historical and musicological insights into Black metaphysics and studies of the African diaspora. -

“A Tremor in the Middle of the Iceberg”: the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Local Voting Rights Activism in Mccomb, Mississippi, 1928-1964

“A Tremor in the Middle of the Iceberg”: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Local Voting Rights Activism in McComb, Mississippi, 1928-1964 Alec Ramsay-Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 1, 2016 Advised by Professor Howard Brick For Dana Lynn Ramsay, I would not be here without your love and wisdom, And I miss you more every day. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... ii Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: McComb and the Beginnings of Voter Registration .......................... 10 Chapter Two: SNCC and the 1961 McComb Voter Registration Drive .................. 45 Chapter Three: The Aftermath of the McComb Registration Drive ........................ 78 Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 102 Bibliography ................................................................................................................. 119 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could not have done this without my twin sister Hunter Ramsay-Smith, who has been a constant source of support and would listen to me rant for hours about documents I would find or things I would learn in the course of my research for the McComb registration -

100Fires Books PO Box 27 Arcata, CA 95518 180-Movement for Democracy and Education PO Box 251701 Little Rock

100Fires Books PO Box 27 Arcata, CA 95518 www.100fires.com 180Movement for Democracy and Education PO Box 251701 Little Rock, AR 72225 USA Phone: (501) 2442439 Fax: (501) 3743935 [email protected] www.corporations.org/democracy/ 1990 Trust Suite 12 Winchester House 9 Cranmer Road London SW9 6EJ UK Phone: 020 7582 1990 Fax: 0870 127 7657 www.blink.org.uk [email protected] 20/20 Vision Jim Wyerman, Executive Director 1828 Jefferson Place NW Washington, DC 20036 Phone: (202) 8332020 Fax: (202) 8335307 www.2020vision.org [email protected] 2030 Center 1025 Connecticut Avenue NW Suite 205 Washington, DC 20036 Phone: (877) 2030ORG Fax: (202) 9555606 www.2030.org [email protected] 21st Century Democrats 1311 L Street, NW Suite 300 Washington, DC 20005 Phone: (202) 6265620 Fax: (202) 3470956 www.21stDems.org [email protected] 4H 7100 Connecticut Avenue Chevy Chase, MD 20815 Phone: (301) 9612983 Fax: (301) 9612894 www.fourhcouncil.edu 50 Years is Not Enough 3628 12th Street NE Washington, DC 20017 Phone: 202IMFBANK www.50years.org [email protected] 911 Media Arts Center Fidelma McGinn, Executive Director 117 Yale Avenue N. Seattle, WA 98109 Phone: (206) 6826552 Fax: (206) 6827422 www.911media.org [email protected] AInfos Radio Project www.radio4all.net AZone 2129 N. Milwaukee Avenuue Chicago, IL 60647 Phone: (312) 4943455 www.azone.org [email protected] A.J. Muste Memorial Institite 339 Lafayette Street New York, NY 10012 Phone: (212) 5334335 www.ajmuste.org [email protected] ABC No Rio 156 Rivington Street New York, NY 100022411 Phone: -

Race, Governmentality, and the De-Colonial Politics of the Original Rainbow Coalition of Chicago

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2012-01-01 In The pirS it Of Liberation: Race, Governmentality, And The e-CD olonial Politics Of The Original Rainbow Coalition Of Chicago Antonio R. Lopez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Lopez, Antonio R., "In The pS irit Of Liberation: Race, Governmentality, And The e-CD olonial Politics Of The Original Rainbow Coalition Of Chicago" (2012). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2127. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2127 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN THE SPIRIT OF LIBERATION: RACE, GOVERNMENTALITY, AND THE DE-COLONIAL POLITICS OF THE ORIGINAL RAINBOW COALITION OF CHICAGO ANTONIO R. LOPEZ Department of History APPROVED: Yolanda Chávez-Leyva, Ph.D., Chair Ernesto Chávez, Ph.D. Maceo Dailey, Ph.D. John Márquez, Ph.D. Benjamin C. Flores, Ph.D. Interim Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Antonio R. López 2012 IN THE SPIRIT OF LIBERATION: RACE, GOVERMENTALITY, AND THE DE-COLONIAL POLITICS OF THE ORIGINAL RAINBOW COALITION OF CHICAGO by ANTONIO R. LOPEZ, B.A., M.A. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO August 2012 Acknowledgements As with all accomplishments that require great expenditures of time, labor, and resources, the completion of this dissertation was assisted by many individuals and institutions. -

Read the Westchester Guardian

PRESORTED STANDARD PERMIT #3036 WHITE PLAINS NY Vol. VII, No. III Thursday, January 16, 2014 $1.00 Westchester’s Most Influential Weekly SHERIF AWAD Ana Ana Page 5 Political PEGGY GODFREY Resolving to Help New Rochelle Youth Predictions Page 8 ROBERT SCOTT Looking at the Stars in Westchester for New Page 9 LUKE HAMILTON No Justice, Year No Peace Page 11 JOHN F. McMULLEN By Hon. RICHARD BRODSKY, The Odyssey Continues Page 3 (Concludes?) Page 12 JOHN SIMON Back From London COURTS PETITION Page 13 NYS Supreme Court Justice The Super Bowl Smith Favorably Ruled BOB MARRONE Weekend: Making It King Henry II, Jaba the for Yonkers Firefighters Hut, Gov. Chris Christie Local 628 with Respect Even Better Page 16 to General Municipal Law Creating the All-American LEE H. HAMILTON 207-a Procedure Holiday Weekend Trust… But Definitely By HEZI ARIS, Page 3 By GLENN SLABY, Page 4 Verify Page 17 WWW.WESTCHESTERGUARDIAN.COM Page 26 THE WESTCHESTER GUARDIAN THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 2012 CLASSIFIED ADS LEGAL NOTICES Office Space Available- FAMILY COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Prime Location, Yorktown Heights COUNTY OF WESTCHESTER 1,000 Sq. Ft.: $1800. Contact Wilca: 914.632.1230 In the Matter of ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE SUMMONS AND INQUEST NOTICE Prime Retail - Westchester County Chelsea Thomas (d.o.b. 7/14/94), Best Location in Yorktown Heights A Child Under 21 Years of Age Dkt Nos. NN-10514/15/16-10/12C 1100 Sq. Ft. Store $3100; 1266 Sq. Ft. store $2800 and 450 Sq. Ft. Store $1200. Adjudicated to be Neglected by NN-2695/96-10/12B Suitable for any type of business. -

Mississippi Freedom Summer: Compromising Safety in the Midst of Conflict

Mississippi Freedom Summer: Compromising Safety in the Midst of Conflict Chu-Yin Weng and Joanna Chen Junior Division Group Documentary Process Paper Word Count: 494 This year, we started school by learning about the Civil Rights Movement in our social studies class. We were fascinated by the events that happened during this time of discrimination and segregation, and saddened by the violence and intimidation used by many to oppress African Americans and deny them their Constitutional rights. When we learned about the Mississippi Summer Project of 1964, we were inspired and shocked that there were many people who were willing to compromise their personal safety during this conflict in order to achieve political equality for African Americans in Mississippi. To learn more, we read the book, The Freedom Summer Murders, by Don Mitchell. The story of these volunteers remained with us, and when this year’s theme of “Conflict and Compromise” was introduced, we thought that the topic was a perfect match and a great opportunity for us to learn more. This is also a meaningful topic because of the current state of race relations in America. Though much progress has been made, events over the last few years, including a 2013 Supreme Court decision that could impact voting rights, show the nation still has a way to go toward achieving full racial equality. In addition to reading The Freedom Summer Murders, we used many databases and research tools provided by our school to gather more information. We also used various websites and documentaries, such as PBS American Experience, Library Of Congress, and Eyes on the Prize. -

Radio France. France Inter. Archives Papier Des Émissions De Valli « Système Disque » (2003-2008), « POP Etc

Radio France. France Inter. Archives papier des émissions de Valli « Système disque » (2003-2008), « POP etc. » (2008-2013), « I love USA (moi non plus) » (2004), « il était une femme » (2005), le prix Constantin (2004-2011). 2003-2013 Répertoire numérique détaillé du versement n° 20140302 Établi par Anne Briqueler, Service Archives écrites et Musée - Direction générale déléguée - Radio France Première édition électronique Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 2014 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_055871 Cet instrument de recherche a été rédigé avec un logiciel de traitement de texte. Ce document est écrit en français. Conforme à la norme ISAD(G) et aux règles d'application de la DTD EAD (version 2002) aux Archives nationales, il a reçu le visa du Service interministériel des Archives de France le ..... 2 Archives nationales (France) Sommaire Radio France. France Inter. Archives papier des émissions de Valli. « Système 4 disque » (2003-2008), « Pop etc. » (2008-2013), « I love USA (moi non ... Émissions des grilles de rentrée : Système disque (2003-2008), Pop etc. (2008- 7 2013) Émissions de la grille d'été : I love USA (moi non plus) (2004), Il était une femme 28 (2005), Émissions animées par Valli à l'occasion du Prix Constantin 30 Carnets de notes de Valli 30 3 Archives nationales (France) INTRODUCTION Référence 20140302/1-20140302/82 Niveau de description groupe de documents Intitulé Radio France. France Inter. Archives papier des émissions de Valli. « Système disque » (2003-2008), « Pop etc. » (2008-2013), « I love USA (moi non plus) » (2004), « Il était une femme » (2005), « Le Prix Constantin » (2004-2011) Date(s) extrême(s) 2003-2013 Nom du producteur • Valli • Radio France Importance matérielle et support Le versement comporte 22 cartons d'archives de type « Armic » soit 6,82 ml. -

I Am Not Your Negro

Magnolia Pictures and Amazon Studios Velvet Film, Inc., Velvet Film, Artémis Productions, Close Up Films In coproduction with ARTE France, Independent Television Service (ITVS) with funding provided by Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), RTS Radio Télévision Suisse, RTBF (Télévision belge), Shelter Prod With the support of Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, MEDIA Programme of the European Union, Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program, National Black Programming Consortium (NBPC), Cinereach, PROCIREP – Société des Producteurs, ANGOA, Taxshelter.be, ING, Tax Shelter Incentive of the Federal Government of Belgium, Cinéforom, Loterie Romande Presents I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO A film by Raoul Peck From the writings of James Baldwin Cast: Samuel L. Jackson 93 minutes Winner Best Documentary – Los Angeles Film Critics Association Winner Best Writing - IDA Creative Recognition Award Four Festival Audience Awards – Toronto, Hamptons, Philadelphia, Chicago Two IDA Documentary Awards Nominations – Including Best Feature Five Cinema Eye Honors Award Nominations – Including Outstanding Achievement in Nonfiction Feature Filmmaking and Direction Best Documentary Nomination – Film Independent Spirit Awards Best Documentary Nomination – Gotham Awards Distributor Contact: Press Contact NY/Nat’l: Press Contact LA/Nat’l: Arianne Ayers Ryan Werner Rene Ridinger George Nicholis Emilie Spiegel Shelby Kimlick Magnolia Pictures Cinetic Media MPRM Communications (212) 924-6701 phone [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com SYNOPSIS In 1979, James Baldwin wrote a letter to his literary agent describing his next project, Remember This House. -

Still Black Still Strong

STIll BLACK,STIll SfRONG l STILL BLACK, STILL STRONG SURVIVORS Of THE U.S. WAR AGAINST BLACK REVOlUTIONARIES DHORUBA BIN WAHAD MUMIA ABU-JAMAL ASSATA SHAKUR Ediled by lim f1elcher, Tonoquillones, & Sylverelolringer SbIII01EXT(E) Sentiotext(e) Offices: P.O. Box 629, South Pasadena, CA 91031 Copyright ©1993 Semiotext(e) and individual contributors. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 978-0-936756-74-5 1098765 ~_.......-.;,;,,~---------:.;- Contents DHORUDA BIN W"AHAD WARWITIllN 9 TOWARD RE'rHINKING SEIl'-DEFENSE 57 THE CuTnNG EDGE OF PRISONTECHNOLOGY 77 ON RACISM. RAp AND REBElliON 103 MUM<A ABU-JAMAL !NrERVIEW FROM DEATH Row 117 THE PRIsON-HOUSE OF NATIONS 151 COURT TRANSCRIPT 169 THE MAN MALCOLM 187 P ANIllER DAZE REMEMBERED 193 ASSATA SHAKUR PRISONER IN THE UNITED STATES 205 CHRONOLOGY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 221 FROM THE FBI PANTHER FILES 243 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS 272 THE CAMPAIGN TO FREE BLACK POLITICALPRISONERS 272 Contents DHORUBA BIN "W AHAD WAKWITIllN 9 TOWARD REnnNKINO SELF-DEFENSE 57 THE CurnNG EOOE OF PRISON TECHNOLOGY 77 ON RACISM, RAp AND REBEWON 103 MUMIA ABU-JAMAL !NrERVIEW FROM DEATH Row 117 THE PRIsoN-HOUSE OF NATIONS 151 COURT TRANSCRIPT 169 THE MAN MALCOLM 187 PANTHER DAZE REMEMBERED 193 ASSATA SHAKUR PJusONER IN THE UNITED STATES 205 CHRONOLOGY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 221 FROM THE FBI PANTHER FILES 243 NOTES ON CONTRmUTORS 272 THE CAMPAIGN TO FREE BUCK POLITICAL PRISONERS 272 • ... Ahmad Abdur·Rahmon (reIeo,ed) Mumio Abu·lomol (deoth row) lundiolo Acoli Alberlo '/lick" Africa (releosed) Ohoruba Bin Wahad Carlos Perez Africa Chorl.. lim' Africa Can,uella Dotson Africa Debbi lim' Africo Delberl Orr Africa Edward Goodman Africa lonet Halloway Africa lanine Phillip. -

Kendrick Lamar Lyrics

Kendrick Lamar Lyrics 『ケンドリック・ラマー・リリック帳 -合唱編- 』 YAPPARIHIPHOP.COM ! 目次 ! good kid, m.A.A.d city 3 02. “Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe 5 03. “Backseat Freestyle” 7 05. “Money Trees” (featuring Jay Rock) 9 06. “Poetic Justice” (featuring Drake) 10 08. “m.A.A.d city” (featuring MC Eiht 12 09. “Swimming Pools (Drank)” (Extended Version) 14 13. “The Recipe” (featuring Dr. Dre) Section 80 16 01. “Fuck Your Ethnicity” 18 02. “Hol’ Up” 20 03. “A.D.H.D” 23 05. “Tammy's Song (Her Evils)” 24 06. “Chapter Six” 25 14. “Blow My High (Members Only)” 27 16. “HiiiPoWeR” Overly Dedicated 28 04. “P&P 1.5 (feat. Ab-Soul)” 30 05. “Alien Girl (Today With Her)” 31 07. “Michael Jordan (feat. Schoolboy Q)” 33 12. “H.O.C” 34 13. “Cut You Off (To Grow Closer)” 36 15. “She Needs Me (Remix) [feat. Dom Kennedy and Murs]“ Other 37 ASAP Rocky “Fucking Problem” ft. Drake, 2 Chainz & Kendrick Lamar 38 “Look Out For Detox” 40 “Westside, Right On Time” ft. Young Jeezy 41 “Cartoon & Cereal” ft. Gunplay 2 Bitch, Don't Kill My Vibe [Hook] I am a sinner who's probably gonna sin again Lord forgive me, Lord forgive me Things I don't understand Sometimes I need to be alone Bitch don't kill my vibe, bitch don't kill my vibe I can feel your energy from two planets away I got my drink, I got my music I would share it but today I'm yelling Bitch don't kill my vibe, bitch don't kill my vibe Bitch don't kill my vibe, bitch don't kill my vibe [Verse 1] Look inside of my soul and you can find gold and maybe get rich Look inside of your soul and you can find out it never exist I can feel the -

Le Reggae.Qxp

1 - Présentation Dossier d’accompagnement de la conférence / concert du vendredi 10 octobre 2008 proposée dans le cadre du projet d’éducation artistique des Trans et des Champs Libres. “Le reggae” Conférence de Alex Mélis Concert de Keefaz & D-roots Dans la galaxie des musiques actuelles, le reggae occupe une place singulière. Héritier direct du mento, du calypso et du ska, son avènement en Jamaïque à la fin des années soixante doit beaucoup aux musiques africaines et cubaines, mais aussi au jazz et à la soul. Et puis, il est lui-même à la source d'autres esthétiques comme le dub, qui va se développer parallèlement, et le ragga, qui apparaîtra à la fin des années quatre-vingt. Au cours de cette conférence, nous retracerons la naissance du reggae sur fond de "sound systems", de culture rastafari, et des débuts de l'indépendance de la Jamaïque. Nous expliquerons ensuite de quelle façon le reggae des origi- nes - le "roots reggae" - s'est propagé en s'"occidentalisant" et en se scindant en plusieurs genres bien distincts, qui vont du très brut au très sophistiqué. Enfin, nous montrerons tous les liens qui se sont tissés au fil des années entre la famille du reggae et celles du rock, du rap, des musiques électroniques, de la chanson, sans oublier des musiques spécifiques d'autres régions du globe comme par exemple le maloya de La Réunion. Alors, nous comprendrons comment la musique d'une petite île des Caraïbes est devenue une musique du monde au sens le plus vrai du terme, puisqu'il existe aujourd'hui des scènes reggae et dub très vivaces et toujours en évolution sur tous les continents, des Amériques à l'Afrique en passant par l'Asie et l'Europe, notamment en Angleterre, en Allemagne et en France.