Chapter IV the Pitcher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Last Week We Read the First Part of Chapter 16 from Luke About the Parable That Jesus Told About the Dishonest Manager

Last week we read the first part of chapter 16 from Luke about the parable that Jesus told about the dishonest manager. That was a very difficult parable to understand because Jesus seems to lift up the dishonest manager as the hero in the story. I shared one possible interpretation that the parable could be about how we are called to be good stewards of the resources that we are given. To not waste our money and resources when they can be used in a way that is pleasing to God. This week we will be reading another parable that Jesus shares. This one is found at the end of the 16th chapter of Luke. I will warn you. It is another parable about money and wealth. And this parable seems to suggest that the way we handle our wealth and money has eternal consequences. We are reminded that parables are stories told by Jesus that used everyday images to convey important messages. Stories which had multiple levels of meaning. The gospel of Luke records lots of parables told by Jesus. In this parable that we are about to read, we will be introduced to a rich man and a poor man named Lazarus. This is the only parable that Jesus tells in which someone is named in the parable. Lazarus here is not to be confused with the Lazarus that was raised from the dead in the gospel according to John. That seems to be a different person. Lazarus is a derivative of the name Eliazar, a name in the Bible which means “God helps.” “God helps.” Some people have given the name Dives to the rich man in this story. -

NCAA Division I Baseball Records

Division I Baseball Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 14 Team Records ........................................................................... 22 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 24 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 All-Time Winningest Teams ................................................ 38 Collegiate Baseball Division I Final Polls ....................... 42 Baseball America Division I Final Polls ........................... 45 USA Today Baseball Weekly/ESPN/ American Baseball Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 46 National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 48 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 49 No-Hitters and Perfect Games by Year .......................... 50 2 NCAA BASEBALL DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Official NCAA Division I baseball records began Season Career with the 1957 season and are based on informa- 39—Jason Krizan, Dallas Baptist, 2011 (62 games) 346—Jeff Ledbetter, Florida St., 1979-82 (262 games) tion submitted to the NCAA statistics service by Career RUNS BATTED IN PER GAME institutions -

Sabermetrics: the Past, the Present, and the Future

Sabermetrics: The Past, the Present, and the Future Jim Albert February 12, 2010 Abstract This article provides an overview of sabermetrics, the science of learn- ing about baseball through objective evidence. Statistics and baseball have always had a strong kinship, as many famous players are known by their famous statistical accomplishments such as Joe Dimaggio’s 56-game hitting streak and Ted Williams’ .406 batting average in the 1941 baseball season. We give an overview of how one measures performance in batting, pitching, and fielding. In baseball, the traditional measures are batting av- erage, slugging percentage, and on-base percentage, but modern measures such as OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage) are better in predicting the number of runs a team will score in a game. Pitching is a harder aspect of performance to measure, since traditional measures such as winning percentage and earned run average are confounded by the abilities of the pitcher teammates. Modern measures of pitching such as DIPS (defense independent pitching statistics) are helpful in isolating the contributions of a pitcher that do not involve his teammates. It is also challenging to measure the quality of a player’s fielding ability, since the standard measure of fielding, the fielding percentage, is not helpful in understanding the range of a player in moving towards a batted ball. New measures of fielding have been developed that are useful in measuring a player’s fielding range. Major League Baseball is measuring the game in new ways, and sabermetrics is using this new data to find better mea- sures of player performance. -

The Rules of Scoring

THE RULES OF SCORING 2011 OFFICIAL BASEBALL RULES WITH CHANGES FROM LITTLE LEAGUE BASEBALL’S “WHAT’S THE SCORE” PUBLICATION INTRODUCTION These “Rules of Scoring” are for the use of those managers and coaches who want to score a Juvenile or Minor League game or wish to know how to correctly score a play or a time at bat during a Juvenile or Minor League game. These “Rules of Scoring” address the recording of individual and team actions, runs batted in, base hits and determining their value, stolen bases and caught stealing, sacrifices, put outs and assists, when to charge or not charge a fielder with an error, wild pitches and passed balls, bases on balls and strikeouts, earned runs, and the winning and losing pitcher. Unlike the Official Baseball Rules used by professional baseball and many amateur leagues, the Little League Playing Rules do not address The Rules of Scoring. However, the Little League Rules of Scoring are similar to the scoring rules used in professional baseball found in Rule 10 of the Official Baseball Rules. Consequently, Rule 10 of the Official Baseball Rules is used as the basis for these Rules of Scoring. However, there are differences (e.g., when to charge or not charge a fielder with an error, runs batted in, winning and losing pitcher). These differences are based on Little League Baseball’s “What’s the Score” booklet. Those additional rules and those modified rules from the “What’s the Score” booklet are in italics. The “What’s the Score” booklet assigns the Official Scorer certain duties under Little League Regulation VI concerning pitching limits which have not implemented by the IAB (see Juvenile League Rule 12.08.08). -

A Statistical Study Nicholas Lambrianou 13' Dr. Nicko

Examining if High-Team Payroll Leads to High-Team Performance in Baseball: A Statistical Study Nicholas Lambrianou 13' B.S. In Mathematics with Minors in English and Economics Dr. Nickolas Kintos Thesis Advisor Thesis submitted to: Honors Program of Saint Peter's University April 2013 Lambrianou 2 Table of Contents Chapter 1: The Study and its Questions 3 An Introduction to the project, its questions, and a breakdown of the chapters that follow Chapter 2: The Baseball Statistics 5 An explanation of the baseball statistics used for the study, including what the statistics measure, how they measure what they do, and their strengths and weaknesses Chapter 3: Statistical Methods and Procedures 16 An introduction to the statistical methods applied to each statistic and an explanation of what the possible results would mean Chapter 4: Results and the Tampa Bay Rays 22 The results of the study, what they mean against the possibilities and other results, and a short analysis of a team that stood out in the study Chapter 5: The Continuing Conclusion 39 A continuation of the results, followed by ideas for future study that continue to project or stem from it for future baseball analysis Appendix 41 References 42 Lambrianou 3 Chapter 1: The Study and its Questions Does high payroll necessarily mean higher performance for all baseball statistics? Major League Baseball (MLB) is a league of different teams in different cities all across the United States, and those locations strongly influence the market of the team and thus the payroll. Year after year, a certain amount of teams, including the usual ones in big markets, choose to spend a great amount on payroll in hopes of improving their team and its player value output, but at times the statistics produced by these teams may not match the difference in payroll with other teams. -

An Offensive Earned-Run Average for Baseball

OPERATIONS RESEARCH, Vol. 25, No. 5, September-October 1077 An Offensive Earned-Run Average for Baseball THOMAS M. COVER Stanfortl University, Stanford, Californiu CARROLL W. KEILERS Probe fiystenzs, Sunnyvale, California (Received October 1976; accepted March 1977) This paper studies a baseball statistic that plays the role of an offen- sive earned-run average (OERA). The OERA of an individual is simply the number of earned runs per game that he would score if he batted in all nine positions in the line-up. Evaluation can be performed by hand by scoring the sequence of times at bat of a given batter. This statistic has the obvious natural interpretation and tends to evaluate strictly personal rather than team achievement. Some theoretical properties of this statistic are developed, and we give our answer to the question, "Who is the greatest hitter in baseball his- tory?" UPPOSE THAT we are following the history of a certain batter and want some index of his offensive effectiveness. We could, for example, keep track of a running average of the proportion of times he hit safely. This, of course, is the batting average. A more refined estimate ~vouldb e a running average of the total number of bases pcr official time at bat (the slugging average). We might then notice that both averages omit mention of ~valks.P erhaps what is needed is a spectrum of the running average of walks, singles, doublcs, triples, and homcruns per official time at bat. But how are we to convert this six-dimensional variable into a direct comparison of batters? Let us consider another statistic. -

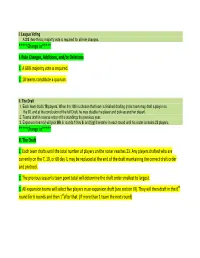

Change To***** I. Rule Changes, Additions, And/Or Deletions 1

I. League Voting A 2/3 (two-thirds) majority vote is required for all rule changes. *****Change to***** I. Rule Changes, Additions, and/or Deletions 1. A 66% majority vote is required. 2. 10 teams constitute a quorum. II. The Draft 1. Each team drafts 18 players. When the 18th is chosen that team is finished drafting (note: team may draft a player on the DL and at the conclusion of the full Draft, he may disable the player and pick-up another player). 2. Teams draft in reverse order of the standings the previous year. 3. Expansion team(s) will pick 6th in rounds 1 thru 6, and first thereafter in each round until his roster contains 23 players. *****Change to***** II. The Draft 1. Each team drafts until the total number of players on the roster reaches 23. Any players drafted who are currently on the 7, 10, or 60 day IL may be replaced at the end of the draft maintaining the correct draft order and protocol. 2. The previous season’s team point total will determine the draft order smallest to largest. 3. All expansion teams will select five players in an expansion draft (see section VI). They will then draft in the 6 th round for 6 rounds and then 1 st after that. (If more than 1 team the next round) III. The Rosters 1. Each team protects 5 players from the previous season roster. 2. Each team may have up to 23 active players. You can have any combination of pitchers and hitters. -

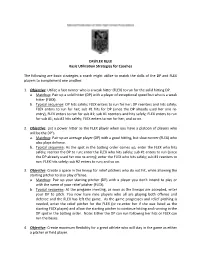

DP/FLEX Strategies for Coaches

DP/FLEX RULE Basic Utilization Strategies for Coaches The following are basic strategies a coach might utilize to match the skills of the DP and FLEX players to complement one another. 1. Objective: Utilize a fast runner who is a weak hitter (FLEX) to run for the solid hitting DP. a. Matchup: Pair up a solid hitter (DP) with a player of exceptional speed but who is a weak hitter (FLEX). b. Typical sequence: DP hits safely; FLEX enters to run for her; DP reenters and hits safely; FLEX enters to run for her; sub #1 hits for DP (since the DP already used her one re- entry), FLEX enters to run for sub #1; sub #1 reenters and hits safely; FLEX enters to run for sub #1; sub #2 hits safely; FLEX enters to run for her; and so on. 2. Objective: List a power hitter as the FLEX player when you have a platoon of players who will be the DP’s. a. Matchup: Pair up an average player (DP) with a good hitting, but slow runner (FLEX) who also plays defense. b. Typical sequence: As the spot in the batting order comes up, enter the FLEX who hits safely; reenter the DP to run; enter the FLEX who hits safely; sub #1 enters to run (since the DP already used her one re-entry); enter the FLEX who hits safely; sub #1 reenters to run; FLEX hits safely; sub #2 enters to run; and so on. 3. Objective: Create a space in the lineup for relief pitchers who do not hit, while allowing the starting pitcher to also play offense. -

2009 Stanford Baseball Baseball Contact: Matt Hodson Email: [email protected] • Office Phone: (650) 725-2959 • Cell Phone: (650) 704-2242

2009 STANFORD BASEBALL Baseball Contact: Matt Hodson Email: [email protected] • Office Phone: (650) 725-2959 • Cell Phone: (650) 704-2242 2009 Stanford Regular Season Schedule STANFORD CARDINAL (13-13) vs. CALIFORNIA GOLDEN BEARS (15-17) Monday, April 13 • 5:00 p.m. • Klein Field at Sunken Diamond (Stanford, CA) Date Opponent Time/Result LHP Scott Snodgress (0-2, 6.60) vs. RHP Kevin Miller (1-2, 4.18) 2/20 Vanderbilt W, 6-5 (10) 2/21 Vanderbilt (Gm. 1) L, 9-12 Vanderbilt (Gm. 2) W, 6-5 2/22 UC Riverside Rained Out 2/25 Saint Mary’s L, 3-5 STANFORD CARDINAL (13-13) at SANTA CLARA BRONCOS (13-17) 2/27 at No. 7 Cal State Fullerton L, 1-8 Wednesday, April 15 • 6:00 p.m. • Schott Stadium (Santa Clara, CA) 2/28 at No. 7 Cal State Fullerton L, 2-3 Both clubs are undecided 3/1 at No. 7 Cal State Fullerton L, 3-9 3/5 Saint Mary’s L, 5-6 All times Pacific; every game is broadcast on KZSU (90.1 FM) and gostanford.com 3/6 No. 2 Texas^ L, 2-6 3/7 No. 2 Texas W, 7-1 Stanford Reaches Halfway Point of Regular Season With Two Midweek Games 3/8 No. 2 Texas L, 1-5 Winners of four of its past five games, seven of its past nine contests and nine of its past 12 out- 3/21 at California* L, 6-7 ings, the Stanford Cardinal (13-13) will reach the halfway point of its 2009 regular season with a pair 3/22 at California* W, 6-5 (12) 3/23 at California* L, 4-11 of midweek games. -

A Sandman Salute As City of New Rochelle Honors Yankees Legend Mariano Rivera with Key to the City & Pinstripe Parade on Sat, July 27

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 19, 2019 Media Contacts For Parade RSVPS: Josh Knoller, Nicholas & Lence Communications, [email protected] Nick Nicholas, Nicholas & Lence Communications, [email protected] PHOTO CREDIT: NEW YORK YANKEES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. A SANDMAN SALUTE AS CITY OF NEW ROCHELLE HONORS YANKEES LEGEND MARIANO RIVERA WITH KEY TO THE CITY & PINSTRIPE PARADE ON SAT, JULY 27 Fans from all over the tri-state invited to celebrate New Ro’s Mo following historic Hall of Fame induction ceremony New Rochelle, NY – It’s one final cheer for the closer of the last century as the City of New Rochelle celeBrates former resident & relief pitcher Mariano Rivera’s unanimous selection into this year’s BaseBall Hall of Fame with `Mariano Rivera Day’ in his adoptive hometown of New Rochelle on Saturday, July 27. With special thanks to the New York Yankees for their sponsorship and support, Mariano Rivera Day will feature a pinstripe parade Beginning at 10 AM that culminates with a celeBration at the Hudson Park Bandshell. Rivera will receive a special proclamation and the Key to the City Before the one and a half mile parade route begins at City Hall on 515 North Avenue (southBound), continuing to Pelham Road and concluding at Hudson Park. Residents, BaseBall fans and the general puBlic are invited to line the streets of New Rochelle to celeBrate the soon-to-Be Hall of Famer. Following the parade, there will Be a celeBration with DJMG- Mike Guiliano, food, and special surprise give-a-ways, courtesy of the New York Yankees, at the Hudson Park Bandshell. -

How to Do Stats

EXPLANATION OF STATS IN SCORE BOOK FIELDING STATISTICS COLUMNS DO - Defensive Outs The number of put outs the team participated in while each player was in the line-up. Defensive outs are used in National Championships as a qualification rule. PO - Put out (10.09) A putout shall be credited to each fielder who (1) Catches a fly ball or a line drive, whether fair or foul. (2) Catches a thrown ball, which puts out a batter or a runner. (3) Tags a runner when the runner is off the base to which he is legally entitled. A – Assist (10.10) Any fielder who throws or deflects a battered or thrown ball in such a way that a putout results or would have except for a subsequent error, will be credited with an Assist. E – Error (10.12) An error is scored against any fielder who by any misplay (fumble, muff or wild throw) prolongs the life of the batter or runner or enables a runner to advance. BATTING STATISTICS COLUMNS PA - Plate Appearance Every time the batter completes his time at bat he is credited with a PA. Note: if the third out is made in the field he does not get a PA but is first to bat in the next innings. AB - At Bat (10.02(a)(1)) When a batter has reached 1st base without the aid of an ‘unofficial time at bat’. i.e. do not include Base on Balls, Hit by a Pitched Ball, Sacrifice flies/Bunts and Catches Interference. R – Runs (2.66) every time the runner crosses home plate scoring a run. -

PITCH COUNT LIMITATION RULES (Effective January, 2018)

PITCH REQUIRED MAXIMUM NUMBER NEXT APPEARANCE CAP COUNT DAYS OF PITCHES ON NEXT Note: Pitch count caps are soft, meaning that the pitcher will PER DAY OF REST APPEARANCE be afforded the opportunity to finish the at‐bat if the maximum for the day is reached in the middle of an at‐bat. 1‐20 0 days 70 pitches A pitcher who throws 1‐20 pitches may pitch on two consecutive days without rest. The maximum number of pitches that can be thrown on the second day is 70. A pitcher who throws on two consecutive days must rest for one day. 21‐35 1 Up to 90 A pitcher who throws 21‐35 pitches must rest for one day. After one day of rest, the pitcher is eligible to pitch to a cap of 90 pitches. 36‐50 2 Up to 90 A pitcher who throws 36‐50 pitches must rest for two days. After two days of rest, the pitcher is eligible to pitch to a cap of 90 pitches. 51‐65 3 Up to 90 A pitcher who throws 51‐65 pitches must rest for three days. After three days of rest, the pitcher is eligible to pitch to a cap of 90 pitches. 66‐90 4 Up to 90 A pitcher who throws 66‐90 pitches must rest for four days. After four days of rest, the pitcher is eligible to pitch to a cap of 90 pitches. PITCH COUNT LIMITATION RULES (Effective January, 2018) The following regulations are to be observed in all IESA interscholastic baseball games.