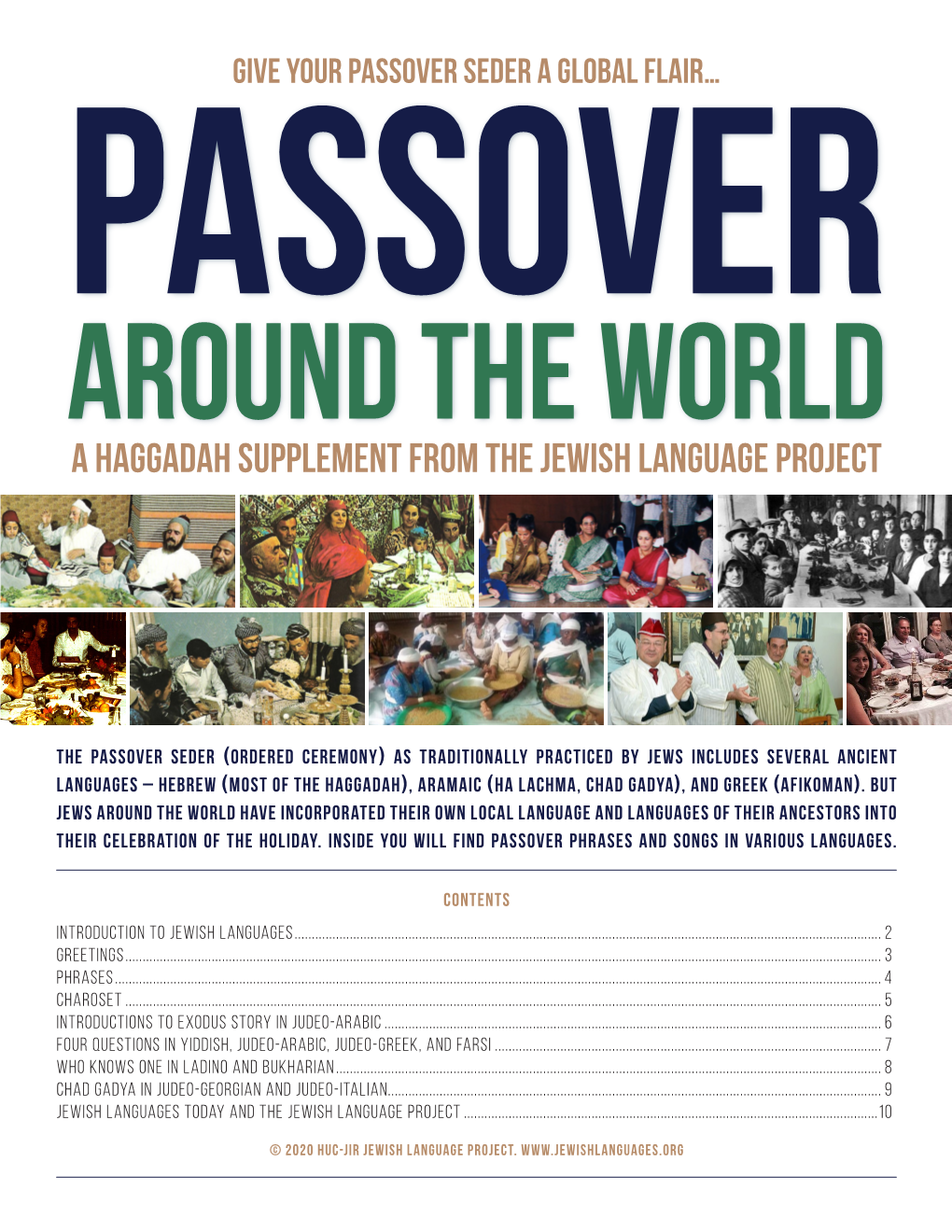

A Haggadah Supplement from the Jewish Language Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

Current Issues in Kurdish Linguistics Current Issues in Kurdish Linguistics 1 Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics

Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics 1 Songül Gündoğdu, Ergin Öpengin, Geofrey Haig, Erik Anonby (eds.) Current issues in Kurdish linguistics Current issues in Kurdish linguistics 1 Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics Series Editor: Geofrey Haig Editorial board: Erik Anonby, Ergin Öpengin, Ludwig Paul Volume 1 2019 Current issues in Kurdish linguistics Songül Gündoğdu, Ergin Öpengin, Geofrey Haig, Erik Anonby (eds.) 2019 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut schen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Informationen sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de/ abrufbar. Diese Veröff entlichung wurde im Rahmen des Elite-Maststudiengangs „Kul- turwissenschaften des Vorderen Orients“ durch das Elitenetzwerk Bayern ge- fördert, einer Initiative des Bayerischen Staatsministeriums für Wissenschaft und Kunst. Die Verantwortung für den Inhalt dieser Veröff entlichung liegt bei den Auto- rinnen und Autoren. Dieses Werk ist als freie Onlineversion über das Forschungsinformations- system (FIS; https://fi s.uni-bamberg.de) der Universität Bamberg erreichbar. Das Werk – ausgenommen Cover, Zitate und Abbildungen – steht unter der CC-Lizenz CC-BY. Lizenzvertrag: Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0. Herstellung und Druck: Digital Print Group, Nürnberg Umschlaggestaltung: University of Bamberg Press © University of Bamberg Press, Bamberg 2019 http://www.uni-bamberg.de/ubp/ ISSN: 2698-6612 ISBN: 978-3-86309-686-1 (Druckausgabe) eISBN: 978-3-86309-687-8 (Online-Ausgabe) URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-opus4-558751 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20378/irbo-55875 Acknowledgements This volume contains a selection of contributions originally presented at the Third International Conference on Kurdish Linguistics (ICKL3), University of Ams- terdam, in August 2016. -

Cultural Orientation | Kurmanji

KURMANJI A Kurdish village, Palangan, Kurdistan Flickr / Ninara DLIFLC DEFENSE LANGUAGE INSTITUTE FOREIGN LANGUAGE CENTER 2018 CULTURAL ORIENTATION | KURMANJI TABLE OF CONTENTS Profile Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 Government .................................................................................................................. 6 Iraqi Kurdistan ......................................................................................................7 Iran .........................................................................................................................8 Syria .......................................................................................................................8 Turkey ....................................................................................................................9 Geography ................................................................................................................... 9 Bodies of Water ...........................................................................................................10 Lake Van .............................................................................................................10 Climate ..........................................................................................................................11 History ...........................................................................................................................11 -

The Hebrew-Jewish Disconnection

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Master’s Theses and Projects College of Graduate Studies 5-2016 The eH brew-Jewish Disconnection Jacey Peers Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses Part of the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Peers, Jacey. (2016). The eH brew-Jewish Disconnection. In BSU Master’s Theses and Projects. Item 32. Available at http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses/32 Copyright © 2016 Jacey Peers This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. THE HEBREW-JEWISH DISCONNECTION Submitted by Jacey Peers Department of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages Bridgewater State University Spring 2016 Content and Style Approved By: ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Joyce Rain Anderson, Chair of Thesis Committee Date ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Anne Doyle, Committee Member Date ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Julia (Yulia) Stakhnevich, Committee Member Date 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my mom for her support throughout all of my academic endeavors; even when she was only half listening, she was always there for me. I truly could not have done any of this without you. To my dad, who converted to Judaism at 56, thank you for showing me that being Jewish is more than having a certain blood that runs through your veins, and that there is hope for me to feel like I belong in the community I was born into, but have always felt next to. -

Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 1

Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 1 Full title: A perceptual dialectological approach to linguistic variation and spatial analysis of Kurdish varieties Main Author: Eva Eppler, PhD, RCSLT, Mag. Phil Reader/Associate Professor in Linguistics Department of Media, Culture and Language University of Roehampton | London | SW15 5SL [email protected] | www.roehampton.ac.uk Tel: +44 (0) 20 8392 3791 Co-author: Josef Benedikt, PhD, Mag.rer.nat. Independent Scholar, Senior GIS Researcher GeoLogic Dr. Benedikt Roegergasse 11/18 1090 Vienna, Austria [email protected] | www.geologic.at Short Title: Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 2 Abstract: This paper presents results of a first investigation into Kurdish linguistic varieties and their spatial distribution. Kurdish dialects are used across five nation states in the Middle East and only one, Sorani, has official status in one of them. The study employs the ‘draw-a-map task’ established in Perceptual Dialectology; the analysis is supported by Geographical Information Systems (GIS). The results show that, despite the geolinguistic and geopolitical situation, Kurdish respondents have good knowledge of the main varieties of their language (Kurmanji, Sorani and the related variety Zazaki) and where to localize them. Awareness of the more diverse Southern Kurdish varieties is less definitive. This indicates that the Kurdish language plays a role in identity formation, but also that smaller isolated varieties are not only endangered in terms of speakers, but also in terms of their representations in Kurds’ mental maps of the linguistic landscape they live in. Acknowledgments: This work was supported by a Santander and by Ede & Ravenscroft Research grant 2016. -

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq

WELCOME TO THE KURDISTAN REGION OF IRAQ Contents President Masoud Barzani 2 Fast facts about the Kurdistan Region of Iraq 3 Overview of the Kurdistan Region 4 Key historical events through the 19th century 9 Modern history 11 The Peshmerga 13 Religious freedom and tolerance 14 The Newroz Festival 15 The Presidency of the Kurdistan Region 16 Structure of the KRG 17 Foreign representation in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq 20 Kurdistan Region - an emerging democracy 21 Focus on improving human rights 23 Developing the Region’s Energy Potential 24 Kurdistan Region Investment Law 25 Tremendous investment opportunities beckon 26 Tourism potential: domestic, cultural, heritage 28 and adventure tourism National holidays observed by 30 KRG Council of Ministers CONTENTS Practical information for visitors to the Kurdistan Region 31 1 WELCOME TO THE KURDISTAN REGION OF IRAQ President Masoud Barzani “The Kurdistan Region of Iraq has made significant progress since the liberation of 2003.Through determination and hard work, our Region has truly become a peaceful and prosperous oasis in an often violent and unstable part of the world. Our future has not always looked so bright. Under the previous regime our people suffered attempted We are committed to being an active member of a federal, genocide. We were militarily attacked, and politically and democratic, pluralistic Iraq, but we prize the high degree of economically sidelined. autonomy we have achieved. In 1991 our Region achieved a measure of autonomy when Our people benefit from a democratically elected Parliament we repelled Saddam Hussein’s ground forces, and the and Ministries that oversee every aspect of the Region’s international community established the no-fly zone to internal activities. -

Where Tulips and Crocuses Are Popular Food Snacks: Kurdish

Pieroni et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2019) 15:59 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-019-0341-0 RESEARCH Open Access Where tulips and crocuses are popular food snacks: Kurdish traditional foraging reveals traces of mobile pastoralism in Southern Iraqi Kurdistan Andrea Pieroni1* , Hawre Zahir2, Hawraz Ibrahim M. Amin3,4 and Renata Sõukand5 Abstract Background: Iraqi Kurdistan is a special hotspot for bio-cultural diversity and for investigating patterns of traditional wild food plant foraging, considering that this area was the home of the first Neolithic communities and has been, over millennia, a crossroad of different civilizations and cultures. The aim of this ethnobotanical field study was to cross-culturally compare the wild food plants traditionally gathered by Kurdish Muslims and those gathered by the ancient Kurdish Kakai (Yarsan) religious group and to possibly better understand the human ecology behind these practices. Methods: Twelve villages were visited and 123 study participants (55 Kakai and 68 Muslim Kurds) were interviewed on the specific topic of the wild food plants they currently gather and consume. Results: The culinary use of 54 folk wild plant taxa (corresponding to 65 botanical taxa) and two folk wild mushroom taxa were documented. While Kakais and Muslims do share a majority of the quoted food plants and also their uses, among the plant ingredients exclusively and commonly quoted by Muslims non-weedy plants are slightly preponderant. Moreover, more than half of the overall recorded wild food plants are used raw as snacks, i.e. plant parts are consumed on the spot after their gathering and only sometimes do they enter into the domestic arena. -

Cuisine of the Islamic World Helena Hallenberg & Irmeli Perho

Cuisine of the Islamic World Helena Hallenberg & Irmeli Perho Original title: Ruokakulttuuri islamin maissa Translation: Owen F. Witesman The translation was kindly subvented by Finnish Literature Exchange FILI. Gaudeamus Helsinki University Press 2010 454 pages, hardbound ISBN 9789524951654 2 Table of Contents Introduction 9 .............................................................................The taste of home 10 ......................................................... Cuisine of the Islamic World 12 .....................................................................Objective of the book 14 .................................................................................... Terms used 15 ...................................................... Quran quotations and Hadiths 16 ................................................. Transliteration and pronunciation 19 ..............................................Cultural selection criterion for foods 27 ............................................................The roots of Islamic cuisine 27 ....................................................................... Arabia before Islam 33 ..................................................................................Bread baking 33 ...........................................................The birth and roots of Islam 35 ..............................Which aroma would the Prophet prefer today? 37 ......................................... Perceptions of impurity and cleanliness 39 ............................................... Islamic -

Discovering the Other Judeo-Spanish Vernacular

ḤAKETÍA: DISCOVERING THE OTHER JUDEO-SPANISH VERNACULAR ALICIA SISSO RAZ VOCES DE ḤAKETÍA “You speak Spanish very well, but why are there so many archaic Cervantes-like words in your vocabulary?” This is a question often heard from native Spanish speakers regarding Ḥaketía, the lesser known of the Judeo-Spanish vernacular dialects (also spelled Ḥakitía, Ḥaquetía, or Jaquetía). Although Judeo-Spanish vernacular is presently associated only with the communities of northern Morocco, in the past it has also been spoken in other Moroccan regions, Algeria, and Gibraltar. Similar to the Djudezmo of the Eastern Mediterranean, Ḥaketía has its roots in Spain, and likewise, it is composed of predominantly medieval Castilian as well as vocabulary adopted from other linguistic sources. The proximity to Spain, coupled with other prominent factors, has contributed to the constant modification and adaptation of Ḥaketía to contemporary Spanish. The impact of this “hispanization” is especially manifested in Haketía’s lexicon while it is less apparent in the expressions and aphorisms with which Ḥaketía is so richly infused.1 Ladino, the Judeo-Spanish calque language of Hebrew, has been common among all Sephardic communities, including the Moroccan one, and differs from the spoken ones.2 The Jews of Spain were in full command of the spoken Iberian dialects throughout their linguistic evolutionary stages; they also became well versed in the official Spanish dialect, Castilian, since its formation. They, however, have continually employed rabbinical Hebrew and Aramaic 1 Isaac B. Benharroch, Diccionario de Haquetía (Caracas: Centro de Estudios Sefardíes de Caracas, 2004), 49. 2 Haїm Vidal Séphiha, “Judeo-Spanish, Birth, Death and Re-birth,” in Yiddish and Judeo-Spanish, A European Heritage, ed. -

Kurdish Spoken Dialect Recogni

Kurdish spoken dialect recognition using x-vector speaker embeddings Arash Amani, Mohammad Mohammadamini, Hadi Veisi To cite this version: Arash Amani, Mohammad Mohammadamini, Hadi Veisi. Kurdish spoken dialect recognition using x-vector speaker embeddings. 2021. hal-03262435 HAL Id: hal-03262435 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03262435 Preprint submitted on 19 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Kurdish spoken dialect recognition using x-vector speaker embeddings Arash Amani1, Mohammad Mohammadamini2, and Hadi Veisi3 1 Asosoft Research group, Iran [email protected] 2 Avignon University LIA (Laboratoire Informatique d'Avignon), Avignon, France [email protected] 3 Faculty of New Sciences and Technologies, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran [email protected] Abstract. This paper presents a dialect recognition system for the Kur- dish language using speaker embeddings. Two main goals are followed in this research: first, we investigate the availability of dialect informa- tion in speaker embeddings, then this information is used for spoken dialect recognition in the Kurdish language. Second, we introduce a pub- lic dataset for Kurdish spoken dialect recognition named Zar. The Zar dataset comprises 16,385 utterances in 49h-36min for five dialects of the Kurdish language (Northern Kurdish, Central Kurdish, Southern Kur- dish, Hawrami, and Zazaki). -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

Traditional Vegetal Food of Yezidis and Kurds in Armenia

JEF42_proof ■ 1 March 2016 ■ 1/10 J Ethn Foods - (2016) 1e10 55 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect 56 57 Journal of Ethnic Foods 58 59 60 journal homepage: http://journalofethnicfoods.net 61 62 63 Original article 64 65 1 Food as a marker for economy and part of identity: traditional vegetal 66 2 67 3 food of Yezidis and Kurds in Armenia 68 4 69 b, * a b 5 Q24 Roman Hovsepyan , Nina Stepanyan-Gandilyan , Hamlet Melkumyan , 70 6 Lili Harutyunyan b 71 7 72 a 8 Q2 Institute of Botany, Yerevan, Armenia 73 b Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Yerevan, Armenia 9 74 10 75 11 article info abstract 76 12 77 13 Article history: 78 14 Q4 The traditional food of the Yezidis and Kurds of Armenia has some particularities and differences Available online xxx compared with the traditional cuisine of Armenians. We correlate these distinctions with the trans- 79 15 humant pastoral lifestyle of the Yezidi and Kurdish people. Traditional dishes of Yezidis and Kurds are 80 16 Keywords: simple. They are mostly made from or contain as a main component lamb and milk products (sometimes 81 17 edible plants beef and chicken, but never pork). The main vegetal components of their traditional food are represented 82 fl 18 avorings by cultivated cereals, grains, and herbs of wild plants. Edible plants gathered from the wild are used 83 gathering 19 primarily for nutritional purposes, for flavoring prepared meals and milk products, and for tea. Kurds 84 20 © traditional food Copyright 2016, Korea Food Research Institute, Published by Elsevier.