Revisiting Kurdish Dialect Geography: Preliminary Findings from the Manchester Database

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Kurmanji Kurdish As

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Kurmanji Kurdish as Spoken in Turkey 1. Special handling of dialects Kurmanji Kurdish is a major branch of modern Kurdish, which belongs to the Iranian group of languages. Kurdish is largely a spoken language with a limited but growing body of modern literature. There are many dialectal varieties of Kurdish spread over a wide area of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran, Armenia and Azerbaijan. There are, in addition, different classifications of Kurdish languages and Kurdish peoples that align dialectal choice with tribal affinity. Linguistic and Kurdish scholars usually describe modern Kurdish as having two closely related major branches: Kurmanji (the northern branch) and Sorani (the southern branch). They are not mutually intelligible (see Thackston (2006) p. vii). The Kurdish Institute summarizes the situation as follows: “Kurdish has two regional standards, namely Kurmanji in Turkey, and Sorani farther east and south. Roughly half of Kurdish speakers live in Turkey.” (see http://www.institutkurde.org/en/ and also http://www.blueglobetranslations.com/about- kurdish-kurmanji-language.html). Within the larger region there are two other languages often associated with ethnic Kurds. These are Dimili (also known as Zazaki) and Gorani. Although sometimes classified as sub-dialects of Kurdish (e.g., Kurdish Language - Britannica Online Encyclopedia), these languages belong to a different group of Iranian languages (see for example, http://kurds_history.enacademic.com/346/Kurmanji). Although Kurmanji Kurdish is spoken across a range of countries, it has the advantage of being spoken by around 60-80% of Kurds and is considered a regional standard. The majority of Kurmanji speakers live in Turkey, making it the ideal country for collection of audio data (see for example, http://linguakurd.blogfa.com/post-106.aspx). -

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

Historical Linguistics and Cognitive Science

5 Historical Linguistics and Cognitive Science Philip Baldi 1 2 & Paola Eulalia Dussias1 (1 Penn State University) (2 University of Cagliari) Abstract In this paper we investigate possible links between historical linguistics and cognitive science, or theory of the mind. Our primary goal is to demonstrate that historically documented processes of a certain type, i.e. those relating to semantic change and grammaticalization, form a unified theoretical bundle which gives insight into the cognitive processes at work in language organization and evolution. We reject the notion that historical phenomena are excluded from cognitive speculation on the grounds that they are untestable. Rather, we argue for an extension of Labov’s uniformitarian doctrine, which states “that the same mechanisms which operated to produce the large-scale changes of the past may be observed operating in the current changes taking place around us.” (Labov, 1972:161). This principle is transferable to the current context in the following way: first, language as a system is no different today than it was millennia ago, easily as far back as diachronic speculation is likely to take us; and second, the human brain is structurally no different today from the brain of humans of up to ten thousand years ago. The cognitive- linguistic parallelism between the past and the present makes speculation possible, in this case about code- switching, even if it is not testable in the laboratory. It further allows us to make forward and backward inferences about both language change and its cognitive underpinnings. Keywords: historical linguistics, cognitive science, code-switching, semantic change, grammaticalization 1. -

Contextualizing Historical Lexicology the State of the Art of Etymological Research Within Linguistics

Contextualizing historical lexicology The state of the art of etymological research within linguistics University of Helsinki, May 15–17, 2017 Abstracts Organized by the project “Inherited and borrowed in the history of the Uralic languages” (funded by Kone Foundation) Contents I. Keynote lectures ................................................................................. 5 Martin Kümmel Etymological problems between Indo-Iranian and Uralic ................ 6 Johanna Nichols The interaction of word structure and lexical semantics .................. 9 Martine Vanhove Lexical typology and polysemy patterns in African languages ...... 11 II. Section papers ................................................................................. 12 Mari Aigro A diachronic study of the homophony between polar question particles and coordinators ............................................................. 13 Tommi Alho & Aleksi Mäkilähde Dating Latin loanwords in Old English: Some methodological problems ...................................................................................... 14 Gergely Antal Remarks on the shared vocabulary of Hungarian, Udmurt and Komi .................................................................................................... 15 Sofia Björklöf Areal distribution as a criterion for new internal borrowing .......... 16 Stefan Engelberg Etymology and Pidgin languages: Words of German origin in Tok Pisin ............................................................................................ 17 László -

Current Issues in Kurdish Linguistics Current Issues in Kurdish Linguistics 1 Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics

Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics 1 Songül Gündoğdu, Ergin Öpengin, Geofrey Haig, Erik Anonby (eds.) Current issues in Kurdish linguistics Current issues in Kurdish linguistics 1 Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics Series Editor: Geofrey Haig Editorial board: Erik Anonby, Ergin Öpengin, Ludwig Paul Volume 1 2019 Current issues in Kurdish linguistics Songül Gündoğdu, Ergin Öpengin, Geofrey Haig, Erik Anonby (eds.) 2019 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut schen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Informationen sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de/ abrufbar. Diese Veröff entlichung wurde im Rahmen des Elite-Maststudiengangs „Kul- turwissenschaften des Vorderen Orients“ durch das Elitenetzwerk Bayern ge- fördert, einer Initiative des Bayerischen Staatsministeriums für Wissenschaft und Kunst. Die Verantwortung für den Inhalt dieser Veröff entlichung liegt bei den Auto- rinnen und Autoren. Dieses Werk ist als freie Onlineversion über das Forschungsinformations- system (FIS; https://fi s.uni-bamberg.de) der Universität Bamberg erreichbar. Das Werk – ausgenommen Cover, Zitate und Abbildungen – steht unter der CC-Lizenz CC-BY. Lizenzvertrag: Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0. Herstellung und Druck: Digital Print Group, Nürnberg Umschlaggestaltung: University of Bamberg Press © University of Bamberg Press, Bamberg 2019 http://www.uni-bamberg.de/ubp/ ISSN: 2698-6612 ISBN: 978-3-86309-686-1 (Druckausgabe) eISBN: 978-3-86309-687-8 (Online-Ausgabe) URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-opus4-558751 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20378/irbo-55875 Acknowledgements This volume contains a selection of contributions originally presented at the Third International Conference on Kurdish Linguistics (ICKL3), University of Ams- terdam, in August 2016. -

Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 1

Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 1 Full title: A perceptual dialectological approach to linguistic variation and spatial analysis of Kurdish varieties Main Author: Eva Eppler, PhD, RCSLT, Mag. Phil Reader/Associate Professor in Linguistics Department of Media, Culture and Language University of Roehampton | London | SW15 5SL [email protected] | www.roehampton.ac.uk Tel: +44 (0) 20 8392 3791 Co-author: Josef Benedikt, PhD, Mag.rer.nat. Independent Scholar, Senior GIS Researcher GeoLogic Dr. Benedikt Roegergasse 11/18 1090 Vienna, Austria [email protected] | www.geologic.at Short Title: Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 2 Abstract: This paper presents results of a first investigation into Kurdish linguistic varieties and their spatial distribution. Kurdish dialects are used across five nation states in the Middle East and only one, Sorani, has official status in one of them. The study employs the ‘draw-a-map task’ established in Perceptual Dialectology; the analysis is supported by Geographical Information Systems (GIS). The results show that, despite the geolinguistic and geopolitical situation, Kurdish respondents have good knowledge of the main varieties of their language (Kurmanji, Sorani and the related variety Zazaki) and where to localize them. Awareness of the more diverse Southern Kurdish varieties is less definitive. This indicates that the Kurdish language plays a role in identity formation, but also that smaller isolated varieties are not only endangered in terms of speakers, but also in terms of their representations in Kurds’ mental maps of the linguistic landscape they live in. Acknowledgments: This work was supported by a Santander and by Ede & Ravenscroft Research grant 2016. -

Lectures on English Lexicology

МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ И НАУКИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ ГОУ ВПО «Татарский государственный гуманитарно-педагогический университет» LECTURES ON ENGLISH LEXICOLOGY Курс лекций по лексикологии английского языка Казань 2010 МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ И НАУКИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ ГОУ ВПО «Татарский государственный гуманитарно-педагогический университет» LECTURES ON ENGLISH LEXICOLOGY Курс лекций по лексикологии английского языка для студентов факультетов иностранных языков Казань 2010 ББК УДК Л Печатается по решению Методического совета факультета иностранных языков Татарского государственного гуманитарно-педагогического университета в качестве учебного пособия Л Lectures on English Lexicology. Курс лекций по лексикологии английского языка. Учебное пособие для студентов иностранных языков. – Казань: ТГГПУ, 2010 - 92 с. Составитель: к.филол.н., доцент Давлетбаева Д.Н. Научный редактор: д.филол.н., профессор Садыкова А.Г. Рецензенты: д.филол.н., профессор Арсентьева Е.Ф. (КГУ) к.филол.н., доцент Мухаметдинова Р.Г. (ТГГПУ) © Давлетбаева Д.Н. © Татарский государственный гуманитарно-педагогический университет INTRODUCTION The book is intended for English language students at Pedagogical Universities taking the course of English lexicology and fully meets the requirements of the programme in the subject. It may also be of interest to all readers, whose command of English is sufficient to enable them to read texts of average difficulty and who would like to gain some information about the vocabulary resources of Modern English (for example, about synonyms -

Kurdish Spoken Dialect Recogni

Kurdish spoken dialect recognition using x-vector speaker embeddings Arash Amani, Mohammad Mohammadamini, Hadi Veisi To cite this version: Arash Amani, Mohammad Mohammadamini, Hadi Veisi. Kurdish spoken dialect recognition using x-vector speaker embeddings. 2021. hal-03262435 HAL Id: hal-03262435 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03262435 Preprint submitted on 19 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Kurdish spoken dialect recognition using x-vector speaker embeddings Arash Amani1, Mohammad Mohammadamini2, and Hadi Veisi3 1 Asosoft Research group, Iran [email protected] 2 Avignon University LIA (Laboratoire Informatique d'Avignon), Avignon, France [email protected] 3 Faculty of New Sciences and Technologies, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran [email protected] Abstract. This paper presents a dialect recognition system for the Kur- dish language using speaker embeddings. Two main goals are followed in this research: first, we investigate the availability of dialect informa- tion in speaker embeddings, then this information is used for spoken dialect recognition in the Kurdish language. Second, we introduce a pub- lic dataset for Kurdish spoken dialect recognition named Zar. The Zar dataset comprises 16,385 utterances in 49h-36min for five dialects of the Kurdish language (Northern Kurdish, Central Kurdish, Southern Kur- dish, Hawrami, and Zazaki). -

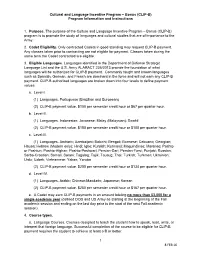

Cultural and Language Incentive Program – Bonus (CLIP-B) Program Information and Instructions

Cultural and Language Incentive Program – Bonus (CLIP-B) Program Information and Instructions 1. Purpose. The purpose of the Culture and Language Incentive Program – Bonus (CLIP-B) program is to promote the study of languages and cultural studies that are of importance to the Army. 2. Cadet Eligibility. Only contracted Cadets in good standing may request CLIP-B payment. Any classes taken prior to contracting are not eligible for payment. Classes taken during the same term the Cadet contracted are eligible. 3. Eligible Languages. Languages identified in the Department of Defense Strategic Language List and the U.S. Army ALARACT 236/2013 provide the foundation of what languages will be authorized for CLIP-B payment. Commonly taught and known languages such as Spanish, German, and French are dominant in the force and will not earn any CLIP-B payment. CLIP-B authorized languages are broken down into four levels to define payment values. a. Level-I. (1) Languages. Portuguese (Brazilian and European) (2) CLIP-B payment value. $100 per semester credit hour or $67 per quarter hour. b. Level-II. (1) Languages. Indonesian; Javanese; Malay (Malaysian); Swahil (2) CLIP-B payment value. $150 per semester credit hour or $100 per quarter hour. c. Level-III. (1) Languages. Amharic; Azerbaijani; Baluchi; Bengali; Burmese; Cebuano; Georgian; Hausa; Hebrew (Modern only); Hindi; Igbo; Kurdish; Kurmanji; Maguindinao; Maranao; Pashto or Pashtun; Pashto-Afghan; Pashto-Peshwari; Persian-Dari; Persian-Farsi; Punjabi; Russian; Serbo-Croatian; Somali; Sorani; Tagalog; Tajik; Tausug; Thai; Turkish; Turkmen; Ukrainian; Urdu; Uzbek; Vietnamese; Yakan; Yoruba (2) CLIP-B payment value. $200 per semester credit hour or $134 per quarter hour. -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

The Importance of Morphology, Etymology, and Phonology

3/16/19 OUTLINE Introduction •Goals Scientific Word Investigations: •Spelling exercise •Clarify some definitions The importance of •Intro to/review of the brain and learning Morphology, Etymology, and •What is Dyslexia? •Reading Development and Literacy Instruction Phonology •Important facts about spelling Jennifer Petrich, PhD GOALS OUTLINE Answer the following: •Language History and Evolution • What is OG? What is SWI? • What is the difference between phonics and •Scientific Investigation of the writing phonology? system • What does linguistics tell us about written • Important terms language? • What is reading and how are we teaching it? • What SWI is and is not • Why should we use the scientific method to • Scientific inquiry and its tools investigate written language? • Goal is understanding the writing system Defining Our Terms Defining Our Terms •Linguistics à lingu + ist + ic + s •Phonics à phone/ + ic + s • the study of languages • literacy instruction based on small part of speech research and psychological research •Phonology à phone/ + o + log(e) + y (phoneme) • the study of the psychology of spoken language •Phonemic Awareness • awareness of phonemes?? •Phonetics à phone/ + et(e) + ic + s (phone) • the study of the physiology of spoken language •Orthography à orth + o + graph + y • correct spelling •Morphology à morph + o + log(e) + y (morpheme) • the study of the form/structure of words •Orthographic phonology • The study of the connection between graphemes and phonemes 1 3/16/19 Defining Our Terms The Beautiful Brain •Phonemeà -

Variation in the Ergative Pattern of Kurmanji Songül Gündoğdu, Muş

Variation in the Ergative Pattern of Kurmanji Songül Gündoğdu, Muş Alparslan University, Muş, Turkey LANGUAGE KEYWORDS: Northern Kurdish (Kurmanji) AREA KEYWORDS: Middle East (Turkey) ABSTRACT (ENGLISH) Kurdish-Kurmanji (or Northern Kurdish) belongs to the Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. This study is dedicated to a deeper understanding of a specific grammatical feature typical of Kurmanji: the ergative structure. Based on the example of this core structure, and with empirical evidence from the Kurmanji dialect of Muş in Turkey, I will discuss the issues of variation and change in Kurmanji, more precisely the ongoing shift from ergative to nominative-accusative structures. The causes for such a fundamental shift, however, are not easy to define. The close historical vicinity to Turkish and Armenian might be a trigger for the shift; another trigger is language-internal (diachronic) change. In sum, the investigated variation sheds light on a fascinating grammatical change in a language that is also sociopolitically in a situation of constant change, movement, and upheaval. ABSTRACT (DEUTSCH) Kurdisch-Kurmanci (oder Nordkurdisch) gehört zum iranischen Zweig der indoeuropäischen Sprachfamilie. Eine zentrale und charakteristische grammatische Struktur dieser Sprache ist der Ergativ; ihm ist der vorliegende Beitrag gewidmet. Am Beispiel des Ergativ werde ich Variation und Wandel im Kurmanci diskutieren und insbesondere auf den Dialekt von Muş (Türkei) eingehen. Dabei zeigt sich, dass sich derzeit im Kurmanci der Wandel von einer Ergativ- zu einer Nominativ-Akkusativ-Sprache vollzieht. Die Ursachen für einen derart grundlegenden Wandel sind nicht leicht zu benennen. Ein Grund mag in der schon historisch engen Nachbarschaft zum Türkischen und Armenischen liegen; ein anderer Grund mag im sprach-internen (diachronen) Wandel des Kurmanci selbst zu finden sein.