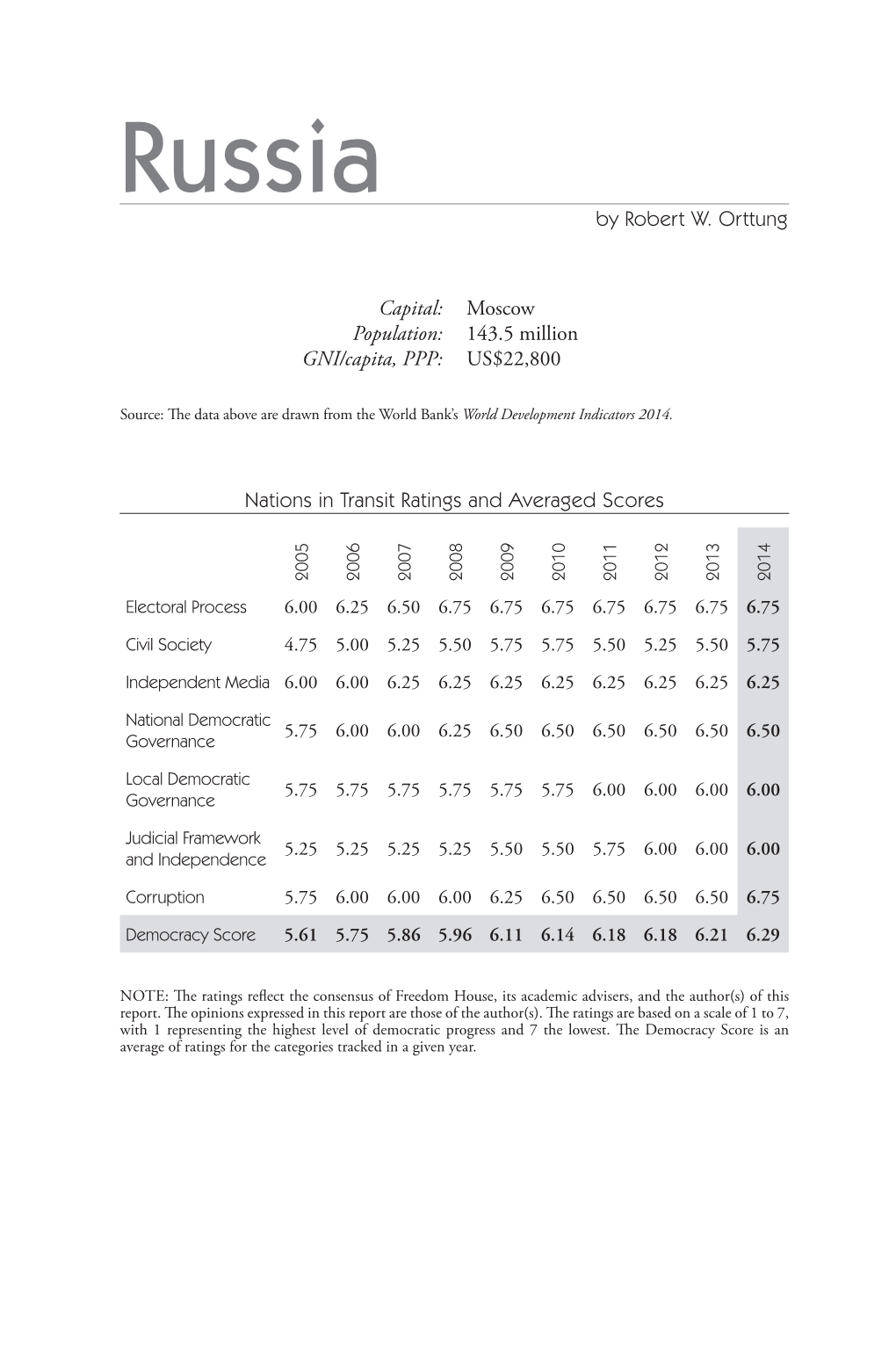

Russia by Robert W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Department of Justice FARA

:U.S. Department of Justice National Securify Division Coun1,rinl1lligt"" om E.xpQrt Control & cliO/'I WasM~on, DC 2QSJO August 17, 2017 BY FEDEX Mikhail Solodovnikov General Manager T &R Productions 1325 G Stre~t, NW, Suite 250 Washington, DC. 20005 Re: Obligation ofT&R Productions, LLC, lo Register Under the Foreign Agents Registration Act Dear Mr. Solodovnikov: Based upon infonnation known to this Qffice, we have determined that T &R Productions, LLC ("T&R"), has an obligation to register pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended, 22 ·u.s.C. §§ 611-621 (1995) ("FARA" or the "Act''). T&R' s obligalion to register arises from its political activities in the United States on behalf of RT and TV-Novosti, both foreign principals under the Act and proxies o f the Russian Government, and its related work within the United States as a publicity agent and infonnation-service employee of TV Novosti. FARA The purpose of FARA is to inform the American public of the activities of agents working for foreign principals to influence U.S. Government officials and/or the American public with reference to the domestic or foreign policies of the United States, or with reference to the political or public interests, policies, or relations of a foreign country or foreign political party. The term "foreign principal" includes "a government of a foreign country" and "a partnership, association, corporation, organization, or other comhination of persons organized under the Jaws of or having its principal place of business in a foreign country." 22 U.S.C. -

Pussy Riot: Art Or Hooliganism? Changing Society Through Means of Participation

Pussy Riot: Art or Hooliganism? Changing Society through Means of Participation Camilla Patricia Reuter Ritgerð til BA-prófs í listfræði Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Pussy Riot: Art or Hooliganism? Changing Society through Means of Participation Camilla Patricia Reuter Lokaverkefni til BA-gráðu í listfræði Leiðsögukennari: Hlynur Helgason Íslensku- og menningadeild Menntavísindasvið Háskóla Íslands Maí 2015 Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til BA- gráðu í listfræði og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Camilla Patricia Reuter 2015 Prentun: Bóksala Menntavísindasviðs Reykjavík, Ísland 2015 Preface In my studies of art history the connection between the past and present has always intrigued me. As a former history major, the interest in historical developments comes hardly as a surprise. This is why I felt that the subject of my essay should concentrate on a recent phenomenon in art with a rich history supporting it. My personal interest in Russian art history eventually narrowed my topics down to Pussy Riot and Voina, which both provide a provocative subject matter. Having spent a semester in St. Petersburg studying the nation’s art history one discovers a palpable connection between politics and art. From Ilya Repin’s masterpieces to the Russian avant-garde and the Moscow Conceptualists, Russian art history is provided with a multitude of oppositional art. The artistic desire to rebel lies in the heart of creativity and antagonism is necessary for the process of development. I wish to thank you my advisor and professor Hlynur Helgason for accepting to guide me in my writing process. Without the theoretical input from my advisor this bachelor’s thesis could not have been written. -

Russian Federation State Actors of Protection

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Russian Federation State Actors of Protection March 2017 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Russian Federation State Actors of Protection March 2017 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Free phone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00800 numbers or these calls may be billed. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Print ISBN 978-92-9494-372-9 doi: 10.2847/502403 BZ-04-17-273-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9494-373-6 doi: 10.2847/265043 BZ-04-17-273-EN-C © European Asylum Support Office 2017 Cover photo credit: JessAerons – Istockphoto.com Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO Country of Origin Report: Russian Federation – State Actors of Protection — 3 Acknowledgments EASO would like to acknowledge the following national COI units and asylum and migration departments as the co-authors of this report: Belgium, Cedoca (Center for Documentation and Research), Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons Poland, Country of Origin Information Unit, Department for Refugee Procedures, Office for Foreigners Sweden, Lifos, Centre for Country of Origin Information and Analysis, Swedish Migration Agency Norway, Landinfo, Country of -

Mr. Vladimir Putin President of Russia Presidential Executive Office 23

ITUC INTERNATIONAL TRADE UNION CONFEDERATION CSI CONFÉDÉRATION SYNDICALE INTERNATIONALE CSI CONFEDERACIÓN SINDICAL INTERNACIONAL IGB INTERNATIONALER GEWERKSCHAFTSBUND MICHAEL SOMMER Mr. Vladimir Putin PRESIDENT PRÉSIDENT President of Russia PRÄSIDENT PRESIDENTE Presidential Executive Office SHARAN BURROW 23, Ilyinka Street, GENERAL SECRETARY Moscow SECRÉTAIRE GÉNÉRALE GENERALSEKRETÄRIN 103132 SECRETARIA GENERAL Russia HTUR/NT Brussels, 22 November 2013 Aeroflot pressures on Sheremetevo Trade Union of Airline Pilots (ShPLS) President Putin, I am writing on behalf of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), which represents 175 million workers in 156 countries and territories - including Russia - to express my serious concerns regarding the arrest, detention and prosecution of several trade union leaders, members of the Sheremetevo Trade Union of Airline Pilots (ShPLS). I have been informed by the ITUC affiliate, the Russian Confederation of Labor (KTR), that on October 18th and 20th, Alexei Shliapnikov, Valery Pimoshenko, and Sergei Knyshov, leaders and activists of the Sheremetevo Trade Union of Airline Pilots (ShPLS), were arrested by the police. They are currently under criminal investigation for an alleged attempt to extort a large sum of money from JSC Aeroflot. They are kept in police custody at least till December 19th and face charges that carry prison terms of up to ten years. According to KTR, those events seem to be part of an on-going Aeroflot campaign against the airline pilots’ union. It is worth noting that shortly before these events took place, the union won a major court victory against the Aeroflot Company. The court ruled that Aeroflot must pay its pilots over Rub 1 billion in unpaid wages for night work and hazardous work in 2011/2012. -

Russia 2012-2013: Attack on Freedom / 3 Introduction

RUSSIA 2012-2013 : Attack on Freedom Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, February 2014 / N°625a Cover photo: Demonstration in front of the State Duma (Russian Parliament) in Moscow on 18 July 2013, after the conviction of Alexei Navalny. © AFP PHOTO / Ivan Novikov 2 / Titre du rapport – FIDH Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 1. Authoritarian Methods to Suppress Rights and Freedoms -------------------------------- 6 2. Repressive Laws ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 8 2.1. Restrictions on Freedom -

Internet Freedom in Vladimir Putin's Russia: the Noose Tightens

Internet freedom in Vladimir Putin’s Russia: The noose tightens By Natalie Duffy January 2015 Key Points The Russian government is currently waging a campaign to gain complete control over the country’s access to, and activity on, the Internet. Putin’s measures particularly threaten grassroots antigovernment efforts and even propose a “kill switch” that would allow the government to shut down the Internet in Russia during government-defined disasters, including large-scale civil protests. Putin’s campaign of oppression, censorship, regulation, and intimidation over online speech threatens the freedom of the Internet around the world. Despite a long history of censoring traditional media, the Russian government under President Vladimir Putin for many years adopted a relatively liberal, hands-off approach to online speech and the Russian Internet. That began to change in early 2012, after online news sources and social media played a central role in efforts to organize protests following the parliamentary elections in December 2011. In this paper, I will detail the steps taken by the Russian government over the past three years to limit free speech online, prohibit the free flow of data, and undermine freedom of expression and information—the foundational values of the Internet. The legislation discussed in this paper allows the government to place offending websites on a blacklist, shut down major anti-Kremlin news sites for erroneous violations, require the storage of user data and the monitoring of anonymous online money transfers, place limitations on 1 bloggers and scan the network for sites containing specific keywords, prohibit the dissemination of material deemed “extremist,” require all user information be stored on data servers within Russian borders, restrict the use of public Wi-Fi, and explore the possibility of a kill-switch mechanism that would allow the Russian government to temporarily shut off the Internet. -

Human Rights Impact Assessment of the Covid-19 Response in Russia

HUMAN RIGHTS IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE COVID-19 RESPONSE IN RUSSIA August 2020 Cover photo: © Анна Иларионова/Pixabay IPHR - International Partnership for Human Rights (Belgium) W IPHRonline.org @IPHR E [email protected] @IPHRonline Public Verdict Foundation W http://en.publicverdict.org/ @fondov Table of Contents I. Executive summary 4 II. Methodology 5 III. Brief country information 6 IV. Incidence of COVID-19 in Russia 7 V. The Russian Authorities’ Response to Covid-19 and its Impact on Human Rights 8 VI. Summary of Key Findings 42 VII. Recommendations 45 I. Executive summary What are the impacts on human rights of the restrictive measures imposed by the Government of Russia in response to the COVID-19 pandemic? How have the Russian authorities complied with international human rights standards while implementing measures to combat the spread of Covid-19? These questions lie at the heart of this study by International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) and Public Verdict Foundation. This study examines these measures through a human rights lens of international, regional human rights treaties of core and soft law (non-binding) standards. Through our monitoring, we have identified the following key points on how the COVID-19 pandemic was handled in Russia from mid-March until mid-July 2020: In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian authorities implemented strict quarantine measures at an early stage, restricting the movements and freedoms of the citizens of the country. The first case of COVID-19 in Russia was officially registered on 2 March 2020, in the vicinity of Moscow.1 The virus began spreading across the country a few weeks later but Moscow has remained the epicentre of the outbreak in Russia. -

Understanding the Financial Times Executive Education Rankings: a 360‐Degree Review

Understanding the Financial Times Executive Education Rankings: A 360‐Degree Review Original Research Sponsored by September 12, 2015 Tom Cavers, James Pulcrano, Jenny Stine Preface: UNICON statement accompanying the research report Understanding the Financial Times Executive Education Rankings: A 360-Degree Review UNICON – The International University Consortium for Executive Education UNICON is a global consortium of business-school-based executive education organizations. Its primary activities include conferences, research, benchmarking, sharing of best practices, staff development, recruitment/job postings, information-sharing, and extensive networking among members, all centered on the business and practice of business-school-based executive education. The UNICON Research Committee The UNICON Research Committee advises the UNICON Board of Directors on research priorities, cultivates a network of research resources and manages the overall research pipeline and projects. The Research Committee is made up of volunteers from UNICON’s member organizations. UNICON Research Report: Understanding the Financial Times Executive Education Rankings: A 360- Degree Review The Financial Times (FT) annual rankings of non-degree Executive Education providers are the best known and most discussed in the industry. In late 2014, the UNICON Research Committee commissioned and the UNICON Board approved the UNICON research project “Understanding the Financial Times Executive Education Rankings: A 360-Degree Review” in large measure to better understand and address many recurring questions about the FT’s ranking system. UNICON is a diverse organization, with representation from over 100 schools. In addition to size and geography, schools are diversified by the expertise, reputation and strength of their faculty, the types and sizes of their customers, and increasingly the breadth and depth of their executive education portfolios. -

Russia's Economic Prospects in the Asia Pacific Region

Journal of Eurasian Studies 7 (2016) 49–59 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Eurasian Studies journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/euras Russia’s economic prospects in the Asia Pacific Region Stephen Fortescue University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Russia has declared a priority interest in developing a strong economic relationship with Received 25 November 2014 the Asia Pacific Region. There has been considerable internal debate over the best strate- Accepted 15 May 2015 gic approach to such a relationship. While a policy victory has been won by a strategy focusing Available online 29 October 2015 on the export into the region of manufactured goods and services, a resource-export strat- egy is still dominant in practice and funding. Here the prospects of each strategy are assessed. Keywords: Regarding resource exports, hydrocarbons, copper and iron ore prospects are reviewed, but Russian Far East most detail is provided on the coal sector. That involves an account of infrastructure issues, Asia Pacific Region Coal exports including a major debate over the expansion of the BAM and TransSiberian railways. The BAM analysis suggests that Russia will struggle both to revitalise the Russian Far East through TransSiberian railway manufacturing exports to the APR and to replace revenues earned through resource exports to the West through an economic ‘turn to the East’. Copyright © 2015 Production and hosting by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of Asia-Pacific Research Center, Hanyang University. 1. Introduction The new priority has produced a fierce policy debate (Fortescue, 2015), behind which is a tension between two In recent years Russia has – not for the first time – de- reasons for economic engagement with the APR. -

Regional Elections and Political Stability in Russia : E Pluribus Unum

TITLE : REGIONAL ELECTIONS AND POLITICAL STABILITY IN RUSSIA : E PLURIBUS UNUM AUTHOR : JEFFREY W . HAHN, Villanova University THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FO R EURASIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE VIII PROGRA M 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D .C . 20036 LEGAL NOTICE The Government of the District of Columbia has certified an amendment of th e Articles of Incorporation of the National Council for Soviet and East Europea n Research changing the name of the Corporation to THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FO R EURASIANANDEAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH, effective on June 9, 1997. Grants , contracts and all other legal engagements of and with the Corporation made unde r its former name are unaffected and remain in force unless/until modified in writin g by the parties thereto . PROJECT INFORMATION : ' CONTRACTOR : Villanova Universit y PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Jeffrey W. Hah n COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 812-06 g DATE : September 25, 1997 COPYRIGHT INFORMATION Individual researchers retain the copyright on their work products derived from researc h funded by contract or grant from the National Council for Eurasian and East Europea n Research. However, the Council and the United States Government have the right t o duplicate and disseminate, in written and electronic form, this Report submitted to th e Council under this Contract or Grant, as follows : Such dissemination may be made by th e Council solely (a) for its own internal use, and (b) to the United States Government (1) fo r its own internal use ; (2) for further dissemination to domestic, international and foreign governments, entities and individuals to serve official United States Government purposes ; and (3) for dissemination in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of the United States Government granting the public rights of access to document s held by the United States Government . -

A Region with Special Needs the Russian Far East in Moscow’S Policy

65 A REGION WITH SPECIAL NEEDS THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST IN MOSCOW’s pOLICY Szymon Kardaś, additional research by: Ewa Fischer NUMBER 65 WARSAW JUNE 2017 A REGION WITH SPECIAL NEEDS THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST IN MOSCOW’S POLICY Szymon Kardaś, additional research by: Ewa Fischer © Copyright by Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia / Centre for Eastern Studies CONTENT EDITOR Adam Eberhardt, Marek Menkiszak EDITOR Katarzyna Kazimierska CO-OPERATION Halina Kowalczyk, Anna Łabuszewska TRANSLATION Ilona Duchnowicz CO-OPERATION Timothy Harrell GRAPHIC DESIGN PARA-BUCH PHOTOgrAPH ON COVER Mikhail Varentsov, Shutterstock.com DTP GroupMedia MAPS Wojciech Mańkowski PUBLISHER Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia Centre for Eastern Studies ul. Koszykowa 6a, Warsaw, Poland Phone + 48 /22/ 525 80 00 Fax: + 48 /22/ 525 80 40 osw.waw.pl ISBN 978-83-65827-06-7 Contents THESES /5 INTRODUctiON /7 I. THE SPEciAL CHARActERISticS OF THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST AND THE EVOLUtiON OF THE CONCEPT FOR itS DEVELOPMENT /8 1. General characteristics of the Russian Far East /8 2. The Russian Far East: foreign trade /12 3. The evolution of the Russian Far East development concept /15 3.1. The Soviet period /15 3.2. The 1990s /16 3.3. The rule of Vladimir Putin /16 3.4. The Territories of Advanced Development /20 II. ENERGY AND TRANSPORT: ‘THE FLYWHEELS’ OF THE FAR EAST’S DEVELOPMENT /26 1. The energy sector /26 1.1. The resource potential /26 1.2. The infrastructure /30 2. Transport /33 2.1. Railroad transport /33 2.2. Maritime transport /34 2.3. Road transport /35 2.4. -

The Long Arm of Vladimir Putin: How the Kremlin Uses Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties to Target Its Opposition Abroad

The Long Arm of Vladimir Putin: How the Kremlin Uses Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties to Target its Opposition Abroad Russia Studies Centre Policy Paper No. 5 (2015) Dr Andrew Foxall The Henry Jackson Society June 2015 THE LONG ARM OF VLADIMIR PUTIN Summary Over the past 15 years, there has been – and continues to be – significant interchange between Western and Russian law-enforcement agencies, even in cases where Russia’s requests for legal assistance have been politicaLLy motivated. Though it is the Kremlin’s warfare that garners the West’s attention, its ‘lawfare’ poses just as significant a threat because it undermines the rule of law. One of the chief weapons in Russia’s ‘lawfare’ is the so-called ‘Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty’ (MLAT), a bilateral agreement that defines how countries co-operate on legal matters. TypicaLLy, the Kremlin will fabricate a criminaL case against an individual, and then request, through the MLAT system, the co-operation of Western countries in its attempts to persecute said person. Though Putin’s regime has been mounting, since 2012, an escalating campaign against opposition figures, the Kremlin’s use of ‘lawfare’ is nothing new. Long before then, Russia requested – and received – legal assistance from Western countries on a number of occasions, in its efforts to extradite opposition figures back to Russia. Western countries have complied with Russia’s requests for legal assistance in some of the most brazen and high-profile politicaLLy motivated cases in recent history, incLuding: individuals linked with Mikhail Khodorkovsky and the Yukos affair; Bill Browder and others connecteD to Hermitage Capital Management; and AnDrey Borodin and Bank of Moscow.