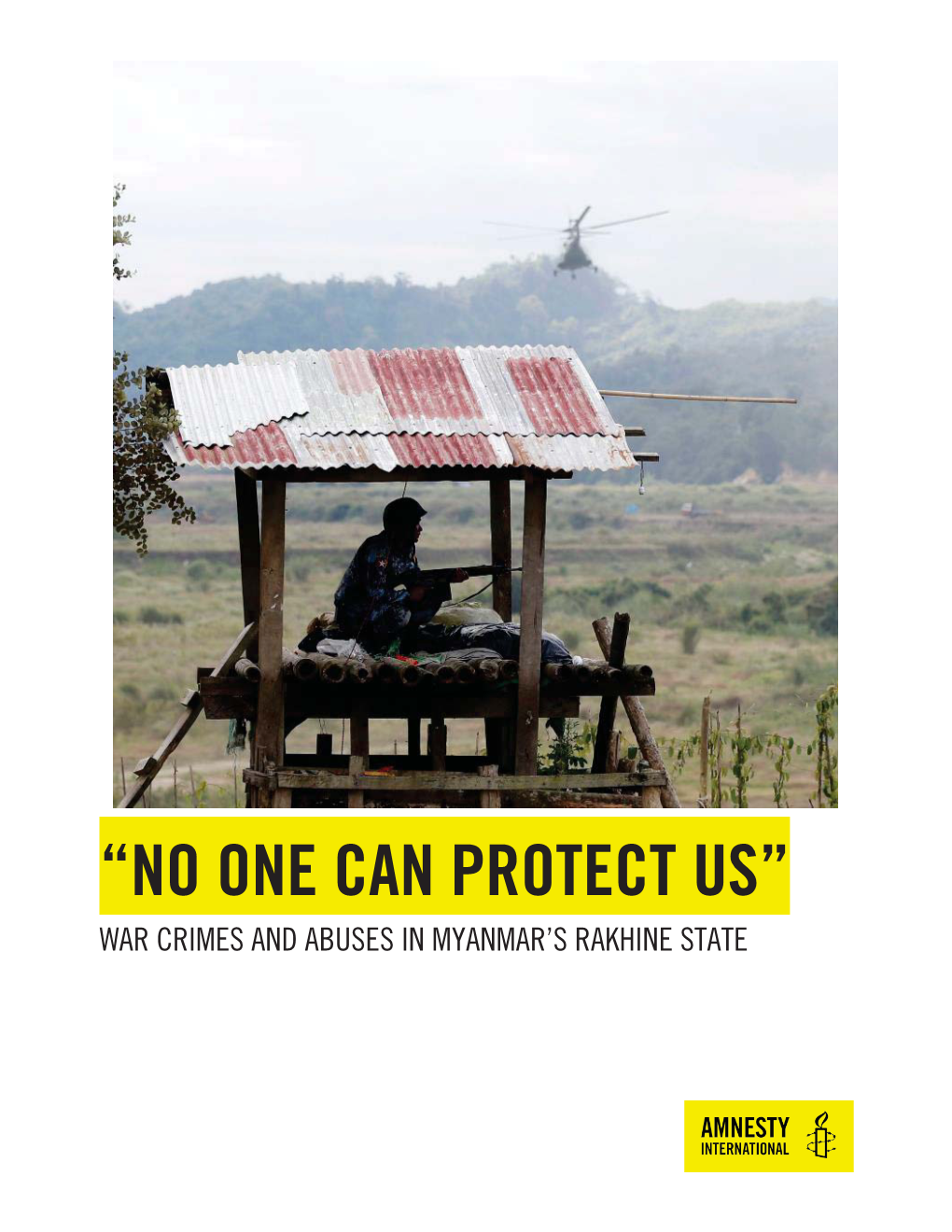

War Crimes and Abuses in Myanmar's Rakhine State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

Report on Tourism in Burma March 2011

Report on Tourism in Burma March 2011 Info Birmanie 74, rue Notre Dame des champs 75006 Paris www.info-birmanie.org e-mail : [email protected] 1. Introduction (p.1) 2 . The History of Tourism in Burma (p.2) 3. The issue of tourism in Burma (p.3 to 9) The Reasons for a Call to Boycott Tourism in Burma : Illusions & Realities 4. An Analysis of the Junta’s Economic Supports (p.10 to 14) Revenues Transport Hotels 5 . Accessible Tourist Zones (p.15 to 22) 6. Travel Agencies Ethics (p.23 to 25) The Absence of Ethics Which Agency to Choose? Which Travel Guide to Use? 7. The Official Statistics of Tourism (p.26 to 27) 8. Conclusion (p.28) 9. Practical Advice (p.29) Chronology (p.30 to 33) 1. Introduction ‘Burma will be here for many years, so tell your friends to visit us later. Visiting now is tantamount to condoning the regime.’ The above statement, which dates from 1999, is a famous quote of Aung San Suu Kyi, Laureate of the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize and leader of the National League for Democracy (NLD), the main Burmese opposition party. It reminds us that since the call to boycott launched in the mid-90s by the Burmese opponents of the military dictatorship, travelling in Burma remains a moral dilemma that is still relevant fifteen years later. However, some plead in favour of Burmese tourism, forgetting both the opposition’s numerous calls to boycott and the terrible situation in which the Burmese people live. In May 2011, the NLD has published a policy paper that put an end to the call for boycott but calls for responsible and independent tourism in Burma. -

Buddhism and State Power in Myanmar

Buddhism and State Power in Myanmar Asia Report N°290 | 5 September 2017 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 149 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Buddhist Nationalism in Myanmar and the Region ........................................................ 3 A. Historical Roots in Myanmar .................................................................................... 3 1. Kingdom and monarchy ....................................................................................... 3 2. British colonial period and independence ........................................................... 4 3. Patriotism and religion ......................................................................................... 5 B. Contemporary Drivers ............................................................................................... 6 1. Emergence of nationalism and violence .............................................................. 6 2. Perceived demographic and religious threats ...................................................... 7 3. Economic and cultural anxieties .......................................................................... 8 4. -

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

Analysis of the Replies to the Questionnaire on "MS Needs and Capacities Regarding Common Pre-Frontier Intelligence Picture (CPIP)" - Compilation of Replies

COUNCIL OF Brussels, 6 July 2011 THE EUROPEAN UNION 12542/11 ADD 1 LIMITE JAI 483 COSI 53 FRONT 87 COMIX 445 NOTE From: Polish delegation To: JHA Counsellors / COSI Support Group No. prev. doc.: CM 6157/10 JAI COSI FRONT COMIX Subject: Implementation of Council Conclusions on 29 Measures for reinforcing the protection of the external borders and combating illegal immigration: analysis of the replies to the questionnaire on "MS needs and capacities regarding Common Pre-Frontier Intelligence Picture (CPIP)" - Compilation of replies Delegations will find attached a compilation of the replies to CM 6157/10 JAI COSI FRONT COMIX. 12542/11 ADD 1 AD/hm 1 DG H 2C LIMITE EN REPLIES OF THE MEMBER STATES / SCHENGEN ASSOCIATED STATES PART I. CURRENT USE OF "CPIP-TYPE" INFORMATION. This part of the questionnaire is intended to establish 1.what information Member States already exchange 2.who is involved in this exchange 3.how can this exchange and already existing mechanisms be most effectively incorporated to EUROSUR. While filling in this part, as the point of departure please refer to the background information on the Technical Study (Annex), however you are invited also to go beyond the scope of the Annex, in your answers. SWEDEN General remark: Please note, that due to an ongoing study in Sweden regarding the requirements of a EUROSUR implementation, we choose not to extensively elaborate with replies to some of the questions in this questionnaire. In Sweden today there is no NCC- function in terms of the Eurosur project. The Swedish Government has assigned the National Police Board to, in cooperation with the Swedish Coast Guard and other relevant authorities, study the requirements for an implementation of the EUROSUR including the NCC- concept. -

That Is Necessary

Belmont University Belmont Digital Repository Honors Theses Belmont Honors Program 4-20-2020 All That Is Necessary Jes Martinez Belmont University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.belmont.edu/honors_theses Part of the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Martinez, Jes, "All That Is Necessary" (2020). Honors Theses. 23. https://repository.belmont.edu/honors_theses/23 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Belmont Honors Program at Belmont Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Belmont Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALL THAT IS NECESSARY written by Jes Martinez Based on Real Events DRAFT B [email protected] (703) 340-5100 TIGHT ON: an ANIMATED MAP of the world. It ZOOMS INTO INDIA and SOUTHEAST ASIA, c. 1050 AD. Then ZOOMS INTO the PAGAN EMPIRE. A WALL OF RED, the MONGOL INVASION, washes over the empire, from the North, c. 1287 AD. The RED DISSOLVES and various CITY-STATES sprout up, rising and falling as they war with each other. EMMA (V.O.) Myanmar’s diverse demographic landscape emerged out of centuries of migration, invasion, and internal turmoil. The city-states DISSOLVE into the rise and fall of dynasties: the PEGU, BAGO, and HANTHARWADDY DYNASTIES (1287-1599), the PINYA DYNASTY (1309-60), the SAGAING DYNASTY (1315-64), the INWA DYNASTY (1365-1555), the TAUNGOO DYNASTY (1486-1752), and the KONBAUNG DYNASTY (1752-1885). EMMA (V.O.) Britain colonized the region-- then called Burma-- and deepened ethno- religious resentments by establishing a system of indirect rule in which they empowered local leaders from the minority groups while suppressing the majority Buddhist Bamar, lighting the flame for the wildfire that Burman religious nationalism was to become. -

Weekly Security Review (27 August – 2 September 2020)

Commercial-In-Confidence Weekly Security Review (27 August – 2 September 2020) Weekly Security Review Safety and Security Highlights for Clients Operating in Myanmar 27 August – 2 September 2020 Page 1 of 27 Commercial-In-Confidence Weekly Security Review (27 August – 2 September 2020) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. 3 Internal Conflict ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Nationwide .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Rakhine State ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Shan State ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Myanmar and the World ......................................................................................................................... 8 Election Watch ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Social and Political Stability ................................................................................................................... 11 Transportation ...................................................................................................................................... -

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020

United Nations A/75/288 General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020 Original: English Seventy-fifth session Item 72 (c) of the provisional agenda* Promotion and protection of human rights: human rights situations and reports of special rapporteurs and representatives Report on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar Note by the Secretary-General The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the General Assembly the report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar and on progress in the situation of human rights in Myanmar, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3. * A/75/150. 20-10469 (E) 240820 *2010469* A/75/288 Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the situation of human rights in Myanmar Summary The independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar issued two reports and four thematic papers. For the present report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights analysed 109 recommendations, grouped thematically on conflict and the protection of civilians; accountability; sexual and gender-based violence; fundamental freedoms; economic, social and cultural rights; institutional and legal reforms; and action by the United Nations system. 2/17 20-10469 A/75/288 I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3, in which the Council requested the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to follow up on the implementation by the Government of Myanmar of the recommendations made by the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar, including those on accountability, and to continue to track progress in relation to human rights, including those of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities, in the country. -

OSCE Border Management Staff College Dushanbe, Tajikistan

Course Catalogue 2017 OSCE Border Management Staff College Dushanbe, Tajikistan BMSC Border Management Staff College COURSE CATALOGUE 2017 Table of Contents About us } 4 CORE ACTIVITIES } 6 RESEARCH CONFERENCES } 10 ROUNDTABLES } 12 THEMATIC COURSES } 16 APPLICATION PROCESS } 30 1 THEMATIC COURSES COURSE CATALOGUE 2017 Director’s Welcome Message Welcome to our Course Catalogue the privilege of working with highly motivated 2017. The OSCE Border professionals from as many as 55 countries, which Management Staff College gave us the opportunity to go through a regular offers multiple learning process of refinement of our curriculum that is opportunities, designed to train constantly responding to current and emerging threats mid- to senior-ranking officials of transnational nature. in the broad range of border security and management domains Quality instruction cannot be limited to the study that make up our field. of well-established theories. It needs to touch the frontiers of different branches of border security and With the on-going support of our donors in 2017 the management in order to provide our participants Border Management Staff College offers a variety of with a clear vision for the future. It is for this purpose programs, including full time and remote education we have a research facilitation pillar that allows courses for the convenience of our participants. We participants of our core courses to work together and make continuous efforts to attract the most prominent provides them with learning through research. practitioners and scholars in the field and provide the fullest overview of border management best practices. The OSCE Border Management Staff College team During our educational activity we not only deliver and I are looking forward to start a new one-year content to our participants, but offer a platform for journey into the field of border management. -

Rakhine State Census Report Volume 3 – K

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Rakhine State Census Report Volume 3 – K Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Rakhine State Report Census Report Volume 3 – K For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014, and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is now my hope that the main results, both Union and each of the State and Region reports, will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national and sub-national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and officers at the State/Region, District and Township Levels, and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. The technical support and our strong desire to follow international standards affirmed our commitment to strict adherence to the guidelines and recommendations, which form part of international best practices for census taking. -

Macadamia Market Systems Analysis Shan State, Myanmar ______March 2020

Macadamia Market Systems Analysis Shan State, Myanmar ___________________________________________________________________________________ March 2020 Commissioned by ILO and authored by Jon Keesecker Acknowledgements The author would like to thank Ko Ko Win and Jonathan Bird for their technical inputs to the research and report writing for this study. This document has been produced for the International Labour Organization (ILO) with funding from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) and the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO). The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the consultants and do not necessarily reflect those of the ILO, NORAD, SECO or any other stakeholder. International Labour Organization (ILO) No.1, Kanbe (Thitsar Street) Yankin Township Yangon, Myanmar. Tel: (95-1) 533538/566539 2 Executive Summary Macadamia is among the rarest tree nuts in the world, but global interest is growing quickly. In 2019, global production of macadamia kernel stood at 59,000 MT, or less than 8% of other individual nuts like almond, walnut, cashew or pistachio. However, macadamia production rose 57% between 2009 and 2019, faster than any other tree nut. Sixty-seven percent of output originates in Australia, South Africa and Kenya, but other sources such as China and Vietnam are also increasing cultivation. Imports have swelled, rising 23% between 2007 and 2017 to reach a total of 32,000 MT. Export markets are fairly consolidated. In 2017, the U.S. accounted for 28% of imports, followed by the EU (20%), China (12%) and Japan (10%). Along with rising prices, global supply value for macadamia rose three-fold from $370 million USD in 2008 to $1.14 trillion in 2019.