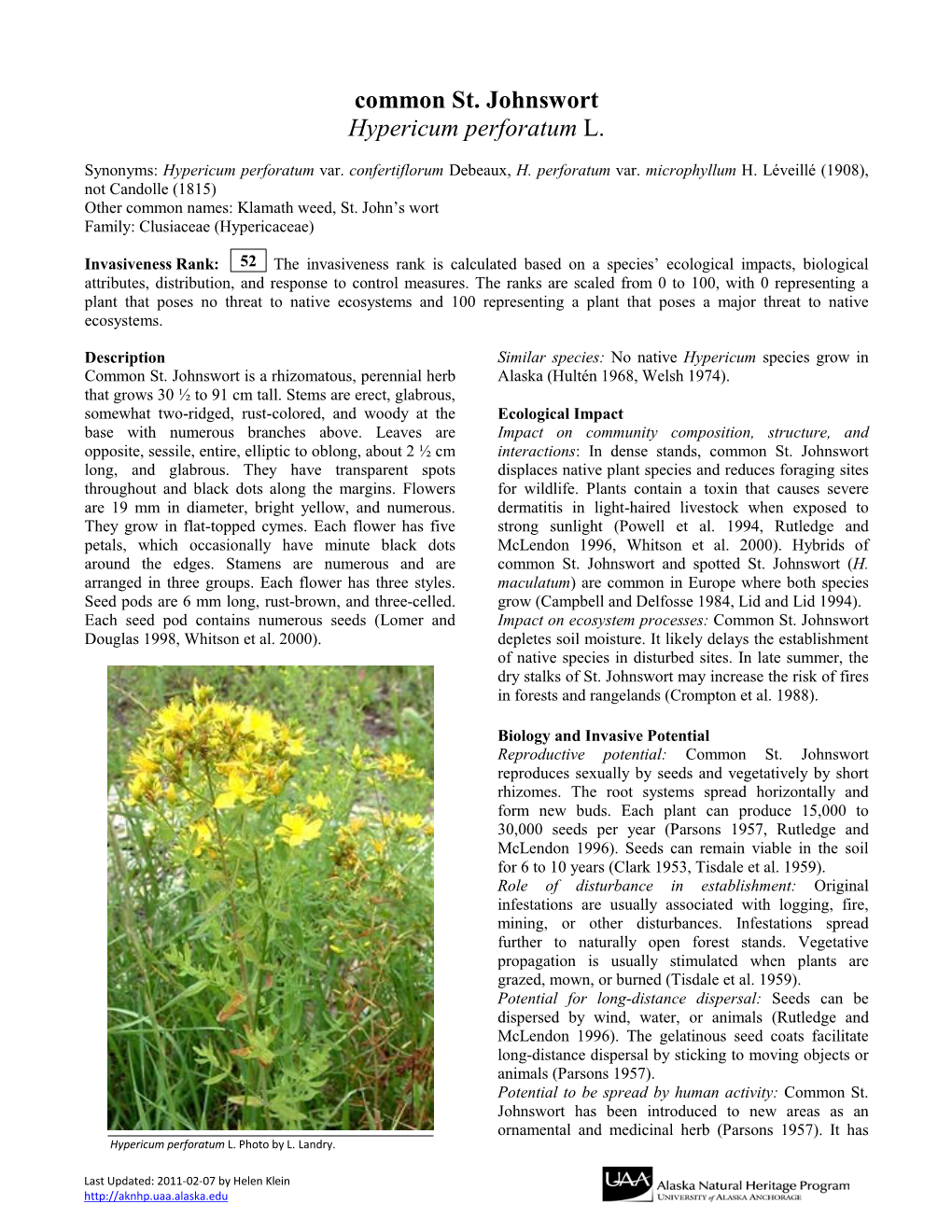

Common St. Johnswort Hypericum Perforatum L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypericaceae Key, Charts & Traits

Hypericaceae (St. Johnswort Family) Traits, Keys, & Comparison Charts © Susan J. Meades, Flora of Newfoundland and Labrador (Aug. 8, 2020) Hypericaceae Traits ........................................................................................................................ 1 Hypericaceae Key ........................................................................................................................... 2 Comparison Charts (3) ................................................................................................................... 4 References ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Hypericaceae Traits • Perennial herbs (in our area). • Stems are erect (lax in plants growing in flooded habitats) and glabrous; terete (round), or square in cross-section; internodes of terete stems with or without 2 low, vertical ridges along their length. • Leaves are cauline, opposite, and usually sessile; blades are simple, linear to ovate, with mostly entire margins; apices are obtuse to rounded; stipules are absent. • Pellucid glands with essential oils appear as translucent dots on the leaves (visible when leaves are held up to the light). • Dark red to blackish glands (with essential oils like hypericin) appear as slender streaks or tiny dots along the leaf, sepal, or petal margins of some species. • Flowers are solitary or 2–40 in terminal and often axillary simple to compound cymes, rarely in panicles. • Flowers are bisexual -

Explosive Radiation in High Andean Hypericum—Rates of Diversification

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 11 September 2013 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00175 Explosive radiation in high Andean Hypericum—rates of diversification among New World lineages Nicolai M. Nürk 1*, Charlotte Scheriau 1 and Santiago Madriñán 2 1 Department of Biodiversity and Plant Systematics, Centre for Organismal Studies Heidelberg, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany 2 Laboratorio de Botánica y Sistemática, Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá DC, Colombia Edited by: The páramos, high-elevation Andean grasslands ranging from ca. 2800 m to the snow Federico Luebert, Freie Universität line, harbor one of the fastest evolving biomes worldwide since their appearance in the Berlin, Germany northern Andes 3–5 million years (Ma) ago. Hypericum (St. John’s wort), with over 65% Reviewed by: of its Neotropical species, has a center of diversity in these high Mountain ecosystems. Andrea S. Meseguer, Institute National de la research agricultural, Using nuclear rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences of a broad sample of France New World Hypericum species we investigate phylogenetic patterns, estimate divergence Colin Hughes, University of Zurich, times, and provide the first insights into diversification rates within the genus in the Switzerland Neotropics. Two lineages appear to have independently dispersed into South America *Correspondence: around 3.5 Ma ago, one of which has radiated in the páramos (Brathys). We find strong Nicolai M. Nürk, Department of Biodiversity and Plant Systematics, support for the polyphyly of section Trigynobrathys, several species of which group within Centre for Organismal Studies Brathys, while others are found in temperate lowland South America (Trigynobrathys Heidelberg, Heidelberg University, s.str.). -

St. John's Wort 2018

ONLINE SERIES MONOGRAPHS The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products Hyperici herba St. John's Wort 2018 www.escop.com The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products HYPERICI HERBA St. John's Wort 2018 ESCOP Monographs were first published in loose-leaf form progressively from 1996 to 1999 as Fascicules 1-6, each of 10 monographs © ESCOP 1996, 1997, 1999 Second Edition, completely revised and expanded © ESCOP 2003 Second Edition, Supplement 2009 © ESCOP 2009 ONLINE SERIES ISBN 978-1-901964-61-5 Hyperici herba - St. John's Wort © ESCOP 2018 Published by the European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP) Notaries House, Chapel Street, Exeter EX1 1EZ, United Kingdom www.escop.com All rights reserved Except for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review no part of this text may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the written permission of the publisher. Important Note: Medical knowledge is ever-changing. As new research and clinical experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment may be required. In their efforts to provide information on the efficacy and safety of herbal drugs and herbal preparations, presented as a substantial overview together with summaries of relevant data, the authors of the material herein have consulted comprehensive sources believed to be reliable. However, in view of the possibility of human error by the authors or publisher of the work herein, or changes in medical knowledge, neither the authors nor the publisher, nor any other party involved in the preparation of this work, warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they are not responsible for any errors or omissions or for results obtained by the use of such information. -

Mindy Goldman, MD Clinical Professor Dept

Managing Menopause Medically and Naturally Mindy Goldman, MD Clinical Professor Dept. of Ob/Gyn and Reproductive Sciences Director, Women’s Cancer Care Program, UCSF Breast Care Center and Women’s Health University of California, San Francisco I have nothing to disclose –Mindy Goldman, MD CASE STUDY 50 yr. old G2P2 peri-menopausal woman presents with complaints of significant night sweats interfering with her ability to sleep. She has mild hot flashes during the day. She has never had a bone mineral density test but her mother had a hip fracture at age 62 due to osteoporosis. Her 46 yr. old sister was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 43, treated with lumpectomy and radiation and currently is doing well. There is no other family history of cancer. Questions 1. Would you offer her MHT? 2. If yes, how long would you continue it? 3. If no, what would you offer for alternative treatments? 4. Would your treatment differ if you knew she had underlying heart disease? Is it safe? How long can I take it? What about Mymy Bones?bones? Will it protect my heart? MHT - 2015 What about my brain? Will I get breast cancer? What about my hot flashes? Menopausal Symptoms Hot flashes Night sweats Sleep disturbances Vaginal dryness/Sexual dysfunction Mood disturbances How to Treat Menopausal Symptoms Hormone therapy Alternatives to hormones Complementary and Integrative Techniques Prior to Women’s Health Initiative Hormone therapy primary treatment of menopausal hot flashes Few women would continue hormones past one year By 1990’s well known -

Hypericaceae) Heritiana S

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 5-19-2017 Systematics, Biogeography, and Species Delimitation of the Malagasy Psorospermum (Hypericaceae) Heritiana S. Ranarivelo University of Missouri-St.Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Ranarivelo, Heritiana S., "Systematics, Biogeography, and Species Delimitation of the Malagasy Psorospermum (Hypericaceae)" (2017). Dissertations. 690. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/690 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Systematics, Biogeography, and Species Delimitation of the Malagasy Psorospermum (Hypericaceae) Heritiana S. Ranarivelo MS, Biology, San Francisco State University, 2010 A Dissertation Submitted to The Graduate School at the University of Missouri-St. Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Biology with an emphasis in Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics August 2017 Advisory Committee Peter F. Stevens, Ph.D. Chairperson Peter C. Hoch, Ph.D. Elizabeth A. Kellogg, PhD Brad R. Ruhfel, PhD Copyright, Heritiana S. Ranarivelo, 2017 1 ABSTRACT Psorospermum belongs to the tribe Vismieae (Hypericaceae). Morphologically, Psorospermum is very similar to Harungana, which also belongs to Vismieae along with another genus, Vismia. Interestingly, Harungana occurs in both Madagascar and mainland Africa, as does Psorospermum; Vismia occurs in both Africa and the New World. However, the phylogeny of the tribe and the relationship between the three genera are uncertain. -

Assessment Report on Hypericum Perforatum L., Herba

European Medicines Agency Evaluation of Medicines for Human Use London, 12 November 2009 Doc. Ref.: EMA/HMPC/101303/2008 COMMITTEE ON HERBAL MEDICINAL PRODUCTS (HMPC) ASSESSMENT REPORT ON HYPERICUM PERFORATUM L., HERBA 7 Westferry Circus, Canary Wharf, London, E14 4HB, UK Tel. (44-20) 74 18 84 00 Fax (44-20) 75 23 70 51 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.emea.europa.eu © European Medicines Agency, 2009. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged TABLE OF CONTENTS I. REGULATORY STATUS OVERVIEW...................................................................................4 II. ASSESSMENT REPORT............................................................................................................5 II.1 INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................6 II.1.1 Description of the herbal substance(s), herbal preparation(s) or combinations thereof 6 II.1.1.1 Herbal substance:........................................................................................................ 6 II.1.1.2 Herbal preparation(s): ................................................................................................ 7 II.1.1.3 Combinations of herbal substance(s) and/or herbal preparation(s)........................... 9 Not applicable. ................................................................................................................................9 II.1.1.4 Vitamin(s) ................................................................................................................... -

Hypericum Gentianoides (L.) BSP Gentian-Leaved St. John's-Wort

Hypericum gentianoides (L.) B.S.P. gentian-leavedgentian-leaved St. John’s-wortSt. John’s-wort, Page 1 State Distribution Photo by Susan R. Crispin Best Survey Period Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Status: State special concern of the occurrences distributed in Wayne, Monroe, Van Buren, and St. Clair counties. Global and state rank: G5/S3 Recognition: H. gentianoides is an annual species Other common names: orange-grass, orange-grass St. ranging from 1-2 dm in height or more, with an erect, John’s-wort central stem that terminates in a number of slender, strongly ascending branches. When crushed, the plant Family: Clusiaceae (St. John’s-wort family); also produces a faint, citrus-like fragrance (which has known as the Guttiferae, and sometimes placed in the also been described as a peach-like odor), as indicated separate family Hypericaceae, similarly long known as by some of the common names for this species. The the St. John’s-wort family. tiny, linear leaves, which are opposite and appressed (oriented to be parallel with the stem), are highly Synonym: Sarothra gentianoides L. reduced, scale-like, and less than 3 mm long. The yellow, five-parted flowers, which areusually solitary Taxonomy: Long treated as a separate family, the in the upper leaf axils, are less than 3 mm broad, Hypericaceae is now combined with the Clusiaceae have 3 styles, and bear fewer than 100 stamens. The (Guttiferae) by most recent treatments “stick-like” appearance of this St. John’s-wort, including the minute, linear leaves, makes it unlikely that this Range: Primarily occurring in eastern North America, will be confused with another species. -

Dietary Supplements Compendium Volume 1

2015 Dietary Supplements Compendium DSC Volume 1 General Notices and Requirements USP–NF General Chapters USP–NF Dietary Supplement Monographs USP–NF Excipient Monographs FCC General Provisions FCC Monographs FCC Identity Standards FCC Appendices Reagents, Indicators, and Solutions Reference Tables DSC217M_DSCVol1_Title_2015-01_V3.indd 1 2/2/15 12:18 PM 2 Notice and Warning Concerning U.S. Patent or Trademark Rights The inclusion in the USP Dietary Supplements Compendium of a monograph on any dietary supplement in respect to which patent or trademark rights may exist shall not be deemed, and is not intended as, a grant of, or authority to exercise, any right or privilege protected by such patent or trademark. All such rights and privileges are vested in the patent or trademark owner, and no other person may exercise the same without express permission, authority, or license secured from such patent or trademark owner. Concerning Use of the USP Dietary Supplements Compendium Attention is called to the fact that USP Dietary Supplements Compendium text is fully copyrighted. Authors and others wishing to use portions of the text should request permission to do so from the Legal Department of the United States Pharmacopeial Convention. Copyright © 2015 The United States Pharmacopeial Convention ISBN: 978-1-936424-41-2 12601 Twinbrook Parkway, Rockville, MD 20852 All rights reserved. DSC Contents iii Contents USP Dietary Supplements Compendium Volume 1 Volume 2 Members . v. Preface . v Mission and Preface . 1 Dietary Supplements Admission Evaluations . 1. General Notices and Requirements . 9 USP Dietary Supplement Verification Program . .205 USP–NF General Chapters . 25 Dietary Supplements Regulatory USP–NF Dietary Supplement Monographs . -

Toxicity Assessment of Hypericum Olympicum Subsp. Olympicum L. On

J Appl Biomed journal homepage: http://jab.zsf.jcu.cz DOI: 10.32725/jab.2020.002 Journal of Applied Biomedicine Original research article Toxicity assessment of Hypericum olympicum subsp. olympicum L. on human lymphocytes and breast cancer cell lines Necmiye Balikci 1, Mehmet Sarimahmut 1, Ferda Ari 1, Nazlihan Aztopal 1, 2, Mustafa Zafer Özel 3, Engin Ulukaya 1, 4, Serap Celikler 1 * 1 Uludag University, Faculty of Science and Arts, Department of Biology, Bursa, Turkey 2 Istinye University, Faculty of Science and Literature, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Istanbul, Turkey 3 University of York, Department of Chemistry, Heslington, York, United Kingdom 4 Istinye University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medical Biochemistry, Istanbul, Turkey Abstract There is a limited number of studies about the constituents ofHypericum olympicum subsp. olympicum and its genotoxic and cytotoxic potency. We examined the possible antigenotoxic/genotoxic properties of methanolic extract of H. olympicum subsp. olympicum (HOE) on human lymphocytes by employing sister chromatid exchange, micronucleus and comet assay and analyzed its chemical composition by GCxGC-TOF/MS. The anti-growth activity against MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines was assessed by using the ATP viability assay. Cell death mode was investigated with fluorescence staining and ELISA assays. The major components of the flower and trunk were determined as eicosane, heptacosane, 2-propen-1-ol, hexahydrofarnesyl acetone and α-muurolene. HOE caused significant DNA damage at selected doses (250–750 µg/ml) while chromosomal damage was observed at higher concentrations (500 and 750 µg/ml). HOE demonstrated anti-growth activity in a dose-dependent manner between 3.13–100 µg/ml. -

Response of Two Chrysolina Species to Different Hypericum Hosts

Seventeenth Australasian Weeds Conference Response of two Chrysolina species to different Hypericum hosts Ronny Groenteman', Simon V. Fowler' and Jon J. Sullivan2 ' Landcare Research, Gerald Street, PO Box 40, Lincoln, New Zealand 2Bio-Protection Research Centre, PO Box 84, Lincoln University, Lincoln, New Zealand Corresponding author: [email protected] SummaryChrysolina hyperici and C. quadrigemina introduced in 1963 but, for many years was thought (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) were introduced to to have failed to establish (reviewed by Hancox et al. New Zealand for biological control of St John's wort 1986). Chrysolina quadrigemina was rediscovered in (SJW), Hypericum perforatum, following successful the late 1980s (Fraser and Emberson 1987). It is now biological control in Australia. In other parts of the abundant in mixed populations with C. hyperici (R. invaded range of SJW worldwide C. quadrigemina is Groenteman personal observations). generally accepted as the more significant contributor St John's wort beetles are not strictly restricted to to SJW successful biocontrol. Their ability to feed and H. perforatum, and are known to be able to develop on develop on indigenous Hypericum species was not other Hypericum species (some examples are reviewed tested. Chrysolina hyperici established well while C. by Harris 1988). New Zealand hosts 10 naturalised quadrigemina was initially thought to have failed to es- (Healy 1972) and four indigenous (Heenan 2008) tablish in New Zealand, although it is now widespread. Hypericum species. Little is known about the suit- Thus, identifying differences between Chrysolina spe- ability and impacts of either Chrysolina species on cies in host preference and performance would have these Hypericum species. -

Attachment A

PLANT EXPLORATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF GEORGIA TO COLLECT GERMPLASM FOR CROP IMPROVEMENT August 26- September 14, 2007 Participants: Joe-Ann H. McCoy, USDA/ ARS/ NPGS, Medicinal Plant Curator North Central Regional Plant Introduction Station G212 Agronomy Hall, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011-1170 Phone: 515-294-2297 Fax: 515-294-1903 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Barbara Hellier, USDA/ ARS/ NPGS, Horticulture Crops Curator Western Regional Plant Introduction Station 59 Johnson Hall, WSU, PO Box 646402, Pullman, WA 99164-6402 Phone: 509-335-3763 Fax: 509-335-6654 Email: [email protected] Georgian Participants: Ana Gulbani Georgian Plant Genetic Resource Centre, Research Institute of Farming Tserovani, Mtskheta, 3300 Georgia. www.cac-biodiversity.org Phone: 995 99 96 7071 Fax: 995 32 26 5256 Email: [email protected] Marina Mosulishvili, Senior Scientist, Institute of Botany Georgian National Museum 3, Rustaveli Ave., Tbilisi 0105 GEORGIA Phone: 995 32 29 4492 / 995 99 55 5089 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Sandro Okropiridze Mosulishvili, Driver Sandro [email protected] (From Left – Marina Mosulishvili, Sandro Okropiridze, Joe-Ann McCoy, Barbara Hellier, Ana Gulbani below Mt. Kazbegi) 2 Acknowledgements: ¾ The expedition was funded by the USDA/ARS Plant Exchange Office, Beltsville, Maryland ¾ Representatives from the Georgia National Museum and the Georgian Plant Genetic Resources Center planned the itinerary and made all transportation, lodging and guide arrangements ¾ Special thanks -

Also in This Issue Web Homepage (

CalEPPC A quarterly publication of the California News Exotic Pest Plant Council Volume 9 • Number 3/4 • 2001 Giant salvinia (Salvinia molesta) Closeup picture from The Nature Conservancy’s Weeds-on-the- Also In This Issue Web Homepage (http://tncweeds.ucdavis.edu). Symposiums & Transitions 3 See 2001 Red Alerts this issue. 2001 Red Alerts 4 Hypericum Alert 6 Keep It in the Garden 7 Cape Ivy Germinating in California & Oregon 8 CalEPPC Seeks Executive Director 10 Membership form 12 CalEPPC News Page 2 Spring 2001 Who We Are 2002 CalEPPC Officers & Board Members CalEPPC NEWS is published quarterly Officers by the California Exotic Pest Plant President Joe DiTomaso [email protected] Council, a non-profit organization. The Vice-president Steve Schoenig [email protected] objects of the organization are to: Secretary Mona Robison [email protected] • provide a focus for issues and Treasurer Becky Waegel [email protected] concerns regarding exotic pest plants Past-president Mike Kelly [email protected] in California; At-large Board Members • facilitate communication and the Carl Bell* [email protected] exchange of information regarding all Matt Brooks** [email protected] aspects of exotic pest plant control Carla Bossard** [email protected] and management; Paul Caron* [email protected] • provide a forum where all interested Tom Dudley** [email protected] parties may participate in meetings Dawn Lawson** [email protected] and share in the benefits from the Alison Stanton** [email protected] information generated by this Scott Steinmaus* [email protected] council; Peter Warner* [email protected] (wk) [email protected] (hm) • promote public understanding Bill Winans* [email protected] regarding exotic pest plants and their control; * Term expires Dec.