W W W. S a F U N D I . C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Colonising Laughter in Mr.Bones and Sweet and Short

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE THE COLONISING LAUGHTER IN MR.BONES AND SWEET AND SHORT TSEPO MAMATU KGAFELA OA MAGOGODI supervisor A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Wits University, Johannesburg, 2006 1 ABSTRACT This research explores the element of the colonial laughter in Leon Schuster’s projects, Mr.Bones and Sweet and Short. I engage with the theories of progressive black scholars in discussing the way Schuster represents black people in these projects. I conclude by probing what the possibilities are in as far as rupturing the paradigms of negative imaging that Schuster, and those that support the idea of white supremacy through their projects, seek/s to normalise. 2 Declaration I declare that this dissertation/thesis is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Masters of the Arts in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination in any other university. TSEPO MAMATU 15 February 2006 3 Dedication We live for those who love us For those who love us true For the heaven that smiles above us and awaits our spirits For the cause that lacks resistance For the future in the distance And the good we must do! Yem-yem, sopitsho zibhentsil’intyatyambo. Mandixhole ngamaxhesha onke, ndizothin otherwise? 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Title page……………………………pg1 -

The Gods Must Be Crazy but the Producers Know Exactly What They Are Doing

_ _ _____ _ _ o _ The Gods Must Be Crazy But the producers know exactly what they are doing BY RICHARD B. LEE The film opens with a highly Both viewers and reviewers are Richard Lee is a Toronto-based anthro romanticized ethnography of the taken in by the charm and inno pologist who has worked with the San primitive Bushmen in their remote cence of the Gods ... especially the for over twenty years. home in "Botswana", (Actually sympathetic portrayal of the non Welcome to Apartheid funland, the film was shot in Namibia). whites. The clever sight gags evoke where white and black mingle eas The voice-over extols the virtues laughter that ignores political ide ily, where the savages are noble of their simple life. Into this ologies. But there is more to this and civilization is in question, and idyllic scene comes a Coke bot film than meets the eye. ... a great where the humour is nonstop. tle thrown from a passing plane. deal more. Discord erupts among the happy First, there is the incredibly These are the images packaged folk as they strive to possess the patronizing attitude towards the in Jamie Uys' hit film, The Gods bottle. Clearly heaven has made Bushmen, or San as I prefer to Must Be Crazy now playing to ca a mistake (hence the film's title) pacity audiences around the world. call them. The Bushman as Noble Savage is a peculiar piece of white South Africa's previous suc South African racial mythology. In cesses in international film distri the popular press the Bushman are bution have served their racism a favorite weekend magazine topic. -

Programming Ideas

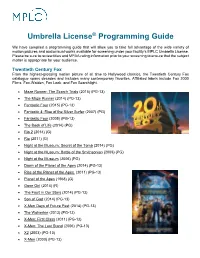

Umbrella License® Programming Guide We have compiled a programming guide that will allow you to take full advantage of the wide variety of motion pictures and audiovisual works available for screening under your facility’s MPLC Umbrella License. Please be sure to review titles and MPAA rating information prior to your screening to ensure that the subject matter is appropriate for your audience. Twentieth Century Fox From the highest-grossing motion picture of all time to Hollywood classics, the Twentieth Century Fox catalogue spans decades and includes many contemporary favorites. Affiliated labels include Fox 2000 Films, Fox-Walden, Fox Look, and Fox Searchlight. • Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials (2015) (PG-13) • The Maze Runner (2014) (PG-13) • Fantastic Four (2015) (PG-13) • Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007) (PG) • Fantastic Four (2005) (PG-13) • The Book of Life (2014) (PG) • Rio 2 (2014) (G) • Rio (2011) (G) • Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014) (PG) • Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009) (PG) • Night at the Museum (2006) (PG) • Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) (PG-13) • Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) (PG-13) • Planet of the Apes (1968) (G) • Gone Girl (2014) (R) • The Fault in Our Stars (2014) (PG-13) • Son of God (2014) (PG-13) • X-Men Days of Future Past (2014) (PG-13) • The Wolverine (2013) (PG-13) • X-Men: First Class (2011) (PG-13) • X-Men: The Last Stand (2006) (PG-13) • X2 (2003) (PG-13) • X-Men (2000) (PG-13) • 12 Years a Slave (2013) (R) • A Good Day to Die Hard (2013) -

In Search of a National Cinema in South Africa

Isabel Balseiro, Ntongela Masilela, eds.. To Change Reels: Film and Film Culture in South Africa. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2003. 272 pp. $39.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-8143-3000-5. Reviewed by Peter Davis Published on H-SAfrica (February, 2004) Against the Odds: In Search of a National Cin‐ imbedded in all areas of flm production and dis‐ ema In South Africa tribution as South Africa. But this statement To Change Reels, edited by Isabel Balseiro and comes with the caveat that what we are talking Ntongela Masilela, looks at South African cinema about is the politics of exclusion. This was the from almost the earliest times up to the present. great paradox: that cinema, the most popular art South Africa early on developed a flm industry, form to evolve during the twentieth century, be‐ but for a number of reasons was limited in its haved in South Africa as if 75 percent of the popu‐ scope by restrictions that were partly self-im‐ lation did not exist. In no other country that as‐ posed. So South African cinema in its entirety is pired to a national cinema did this happen: Amer‐ not a large body of work, but while most of it can‐ ican, British, French, German, Indian, Japanese, not lay claim to the upper reaches of cinematic and Swedish cinemas all built on a solid domestic achievement, almost everything produced re‐ base. Even tiny Denmark did the same, and for wards study, from early epic to flms made for much of the silent period at least, was a world cin‐ miners to the ethnic pulp movies of the 1970s and ema. -

Imaging Africa: Gorillas, Actors and Characters

Imaging Africa: Gorillas, Actors And Characters Africa is defined in the popular imagination by images of wild animals, savage dancing, witchcraft, the Noble Savage, and the Great White Hunter. These images typify the majority of Western and even some South African film fare on Africa. Although there was much negative representation in these films I will discuss how films set in Africa provided opportunities for black American actors to redefine the way that Africans are imaged in international cinema. I conclude this essay with a discussion of the process of revitalisation of South African cinema after apartheid. The study of post-apartheid cinema requires a revisionist history that brings us back to pre-apartheid periods, as argued by Isabel Balseiro and Ntongela Masilela (2003) in their book’s title, To Change Reels. The reel that needs changing is the one that most of us were using until Masilela’s New African Movement interventions (2000a/b;2003). This historical recovery has nothing to do with Afrocentricism, essentialism or African nationalisms. Rather, it involved the identification of neglected areas of analysis of how blacks themselves engaged, used and subverted film culture as South Africa lurched towards modernity at the turn of the century. Names already familiar to scholars in early South African history not surprisingly recur in this recovery, Solomon T. Plaatje being the most notable. It is incorrect that ‘modernity denies history, as the contrast with the past – a constantly changing entity – remains a necessary point of reference’ (Outhwaite 2003: 404). Similarly, Masilela’s (2002b: 232) notion thatconsciousness ‘ of precedent has become very nearly the condition and definition of major artistic works’ calls for a reflection on past intellectual movements in South Africa for a democratic modernity after apartheid. -

Ways of Seeing (In) African Cinema Panel: Selected Filmography 1 The

Ways of Seeing (in) African Cinema panel: Selected Filmography The Higher Learning staff curate the digital resource packages to complement and offer further context to the topics and themes discussed during the various Higher Learning events held at TIFF Bell Lightbox. These filmographies, bibliographies, and additional resources include works directly related to the guests’ career and event’s themes, as well as works that, while seemingly unrelated, were discussed during the event as jumping off points for further research. Please refer to the event video to see how all topics and themes relate to the Higher Learning event. *mentioned or discussed during the panel Sub-Saharan African Feature Films Black Girl. Dir. Ousmane Sembène, 1965, Senegal. 60 mins. Production Co. Les Actualities Françaises / Films Domirev. Mandabi. Dir. Ousmane Sembène, 1968, France and Senegal. 90 mins. Production Co.: Comptoir Français du Film Production (CFFP) / Filmi Domirev. Le Wazzou Polygame. Dir. Oumarou Ganda, 1970, Niger. 50 mins. Production Co.: unknown. Emitaï. Dir. Ousmane Sembène, 1971, Senegal. 101 mins. Production Co.: Metro Pictures. Sambizanga. Dir. Sarah Maldoror, 1972, Angola. 102 mins. Production Co.: unknown. Touki Bouki. Dir. Djibril Diop Mambéty, 1973, Senegal. 85 mins. Production Co.: unknown. Harvest: 3000 Years. Dir. Haile Gerima, 1975, Ethiopia. 150 mins. Production Co.: Mypheduh Films, Inc. Kaddu Beykat. Dir. Safi Faye, 1975, Senegal. 95 mins. Production Co.: Safi Production. Xala. Dir. Ousmane Sembène, 1975, Senegal. 123 mins. Production Co.: Films Domireew / Ste. Me. Production du Senegal. Ceddo. Dir. Ousmane Sembène, 1977, Senegal. 120 mins. Production Co.: unknown. The Gods Must Be Crazy. Dir. Jamie Uys, 1980, Namibia. -

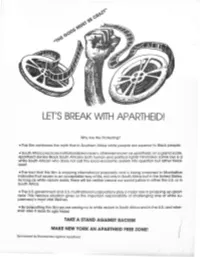

Let's Break with Apartheid!

LET'S BREAK WITH APARTHEID! Why Are We Protesting? • This film reinforces the myth that in Southern Africa white people are superior to Black people. • .South Africa practices institutionalized raCism, otherwise known as apartheid, on a grand scale. Apartheid denies Black South Africans both human and political rights! Filmmaker Jamie Uys is a white South African who does not call this socio-economic system into question but rather trivial izes it. • The fact that this film is enjoying international popularity and is being screened in Manhattan indicates that racism is an acceptable way of life, not only in South Africa but in the United States. As long as white racism exists, there will be neither peace nor social justice in either the U.S. or in South Africa. •The U.S. government and U.S. multinational corporations play a major role in propping up apart heid. This heinous situation gives us the important responsibility of challenging one of white su premacy's most. vital lifelines . • By b6~otting this film we are saying no to white racism in South Africa and in the U.S. and wher ever else it rears its ugly head. TAKE A STAND AGAINST RACISM MAKE NEW YORK AN APARTHEID FREE ZONE! Sponsored by Brooklynites Against Apartheid I MAKING FILMS FOR APARTHEID IS GETTING TO BE A HABIT, LET'S BREAK IT ... "The Gods Must Be Crazy" has receive~d rave reviews as a "comedy". Do you know what you're being csked to laugh at? The San people (a Black nation otherwise known as Bushmen), about whom this film is made, are one .of the oldest civiliz.ations on earth. -

God Must Be Crazy 3 Download

1 / 4 God Must Be Crazy 3 Download QUOTE(amir.asyraf @ Feb 21 2020, 06:24 PM). damn it can't find any torrent for it :( *. If you're looking for Gods must be crazy , i can download .... Find the perfect the gods must be crazy stock photo. Huge collection, amazing choice, 100+ million high quality, affordable RF and RM images. No need to .... The Gods Must Be Crazy Collection chronicles the comic adventures of a Kalahari Bushman named Xixo as his world is invaded by modern civilisation.. Download film god must be crazy 3. The gods must be crazy 3 youtube. The gods must be crazy wikipedia. The gods must be crazy 1980 trailer | n! Xau | marius .... Top 10 Latest English Audio Mp3 Song Free Download : 1 1 Shake It Off ... Bass Meghan Trainor 3 3 Bang Ban Download backing music in midi and CD formats. ... (かくし付き) Download Mp3 Chris Brown Young Thug Go Crazy Instrumental, ... Our goal is to create products that make it easier to perform and mix using all .... the gods must be crazy hindi dubbed, the gods must be crazy hindi dubbed movie download, the gods mu.. I saw The Gods Must Be Crazy back in the 1980s at the Somerville Theatre in Massachussetts, about ... Click here to download the KTabS file. the gods must be crazy 3 tamil dubbed movie download, the gods must be crazy tamil dubbed movie down.. 6 I can't seem to download with mIRC; 7 mIRC XDCC Scripts; 8 XDCC Search ... full moviethe god must be crazy movie free downloadgod must be crazy 3 full ... -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

REPORT REPORT 9 - ** 4 ~7 ,~ 4 9~4~ Vol. 1 No. 1 June 1985 ~©T1i~i~L L3.o. 1o Vo.iNo. 1 REPORT June 1985 Southern Africa REPORT is produced by a volunteer collective of the Toronto Committee for the Liberation of Southern Africa (TCLSAC), 427 Bloor St. W. Toronto, M5S 1X7. Tel. 416- 531-8101. Submissions, suggestions and help with production are welcome and invited. Subscriptions Annual TCLSAC membership and Southern Africa REPORT subscription rates are as follows: Regular (Canada) . $25.00 Unemployed Student ...... Senior . $10.00 Foreign (inc. U.S.A.) . $35.00 Sustainer ........ .$100.00 Contents Editorial .......... ........................ 1 Mozambique 1975-1985 Independence Day ...... .. 2 Dia Da Independencia - a poem ...... ............. 4 Ten Years After ........ ..................... 5 Maxaquene of Mozambique Wins Championship ... ...... 8 South Africa ANC Call to the Nation ............ Namibia Dirty War in Namibia ..... ................... Angola Angola Prepares for 2nd Party Congress ............ Solidarity News Report from N.Y.: Apartheid Issue Heats Up .......... Working Links ........ .................... Reviews The Gods Must Be Crazy ......... 9 . 19 Contributors Jonathan Barker, Nancy Barker, Shirani George, Lee Hemingway, Susan Hurlich, Richard Lee, Lyn Madigan, Judith Marshall, John Saul, Heather Speers, Stephanie Urdang, Joe Vise, Mary Vise I A 2Z 0 To paraphrase Mark Twain, the reports of our death have been greatly exaggerated. TCLSAC lives - and the first issue of Southern Africa Report (formerly TCLSAC Reports) which you now hold in your hand is proof postitve of that fact. True, as some of you will have heard, we've had some trying times during the past year or so: a financial squeeze (which has made it impossible for us to continue with any paid office staff), the impact of a much harsher political climate in the world at large, even some waning of volunteer energies within the Committee itself. -

Beating Around the Bushmen a Controversy Revisited

CCK-9 INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS Beatinq around the Bushmen" a controversy revisited Casey Kelso #2 Wakefield Lodge Wakefield Road, Avondale Harare, Zimbabwe June 30, 1992 Peter Bird Martin Institute of Current World Affairs 4 West Wheelock Street Hanover, New Hampshire 03755 Dear Peter- In a bookshop into which I ventured, there was a line of nervous actors waiting to audition, each hoping for the big break that could launch a movie career. At a glance I could see the South African director's criteria for casting the leading man in a film tentatively titled "A Far Off Place." The young African men had varying degrees of professional polish but all were short and possessed some Bushman characteristics, such as high cheekbones or a rounded face. Each had seen the advertisement in the daily newspaper" ACTOR WANTED OPEN AUDITION Lead role in an international feature film An international company is planning to film a classic African story in Zimbabwe and Namibia. We are looking for a small, coloured actor to play a Bushman the starring role. Do you meet the following requirements? No taller than 5'2" Bushman/San features Speak English 25 35 years old Physically fit "The role of Xhabbo will require considerable research and rehearsal on the part of the actor," said Irmela Erlank, who was assisting the casting director in the search for a new Third World film star. "He must speak English and have discipline, so it has been terribly difficult finding a Bushman like that. They don't want naive actors, since the role is of a mature man who is intelligent and has been around civilization. -

The Varsity Theater: a Case Study of the One-Screen Locally-Owned Movie Theater Business in Iowa

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2012 The aV rsity Theater: A case study of the one-screen locally-owned movie theater business in Iowa Mohammad Sadegh Foghani Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Foghani, Mohammad Sadegh, "The aV rsity Theater: A case study of the one-screen locally-owned movie theater business in Iowa" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12322. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12322 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Varsity Theater: A case study of the one-screen locally-owned movie theater business in Iowa By Mohammad Sadegh Foghani A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Program of Study Committee: Amy Bix, Major Professor Charles M. Dobbs Leland A. Poague Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 Copyright © Mohammad Sadegh Foghani, 2012. All rights reserved. ii Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction .............................................................................................1 1.1. The Nickelodeons and the Prestigious Movie Palaces ..........................................1 1.2. The Art Deco Style, Drive-Ins and First Multiplexes............................................5 1.3. Multiplexes Become Dominant ......................................................................... -

Journal for Academic Excellence

1 June 2016 Volume 4, Issue 5 Journal for Academic Excellence Proceedings Edition of the Seventh Annual Dalton State College Center for Academic Teaching and Learning Conference Excellence Dalton State College A Division of the Office of Dalton State College Faculty Accomplishments Academic Affairs The mission of the CAE is Page 2 to facilitate, support, and enhance the teaching and learning process at Dalton State College. The Center Electronic Rubrics for Evaluating Student Oral Presentations serves to ultimately improve student success Christine Jonick and Jennifer Schneider and achievement of learning outcomes by University of North Georgia promoting the creation of Page 5 effective learning environments through the provision of resources and Engaging Students Through Cinematic Experiences of Diversity and faculty development opportunities. Global Learning Ray-Lynn Snowden University of North Georgia Page 9 Integrating the Capstone Experience: From Negotiations to Grants Bagie M. George Georgia Gwinnett College Page 19 2 Faculty and Staff Accomplishments Ms. Anne Loughren, Ms. Tracey May, Interim Dr. Ronda Ford, adjunct Assistant Director of Campus Coordinator of the Gilmer instructor of flute at Dalton Recreation, Fitness Programs, Campus, graduated from the State College, will be going on a graduated from Georgia Leadership Gilmer class on ten-day tour to Japan with the College and State University May 3. It was a nine-month International Flute Orchestra with a Master of Science in program through the Gilmer during the last two weeks of Health & Human Performance County Chamber of Commerce May. The flute orchestra will with a concentration in Health that involved participants’ perform concerts in Osaka, Promotion.