Ÿþm Icrosoft W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Colonising Laughter in Mr.Bones and Sweet and Short

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE THE COLONISING LAUGHTER IN MR.BONES AND SWEET AND SHORT TSEPO MAMATU KGAFELA OA MAGOGODI supervisor A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Wits University, Johannesburg, 2006 1 ABSTRACT This research explores the element of the colonial laughter in Leon Schuster’s projects, Mr.Bones and Sweet and Short. I engage with the theories of progressive black scholars in discussing the way Schuster represents black people in these projects. I conclude by probing what the possibilities are in as far as rupturing the paradigms of negative imaging that Schuster, and those that support the idea of white supremacy through their projects, seek/s to normalise. 2 Declaration I declare that this dissertation/thesis is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Masters of the Arts in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination in any other university. TSEPO MAMATU 15 February 2006 3 Dedication We live for those who love us For those who love us true For the heaven that smiles above us and awaits our spirits For the cause that lacks resistance For the future in the distance And the good we must do! Yem-yem, sopitsho zibhentsil’intyatyambo. Mandixhole ngamaxhesha onke, ndizothin otherwise? 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Title page……………………………pg1 -

The Gods Must Be Crazy but the Producers Know Exactly What They Are Doing

_ _ _____ _ _ o _ The Gods Must Be Crazy But the producers know exactly what they are doing BY RICHARD B. LEE The film opens with a highly Both viewers and reviewers are Richard Lee is a Toronto-based anthro romanticized ethnography of the taken in by the charm and inno pologist who has worked with the San primitive Bushmen in their remote cence of the Gods ... especially the for over twenty years. home in "Botswana", (Actually sympathetic portrayal of the non Welcome to Apartheid funland, the film was shot in Namibia). whites. The clever sight gags evoke where white and black mingle eas The voice-over extols the virtues laughter that ignores political ide ily, where the savages are noble of their simple life. Into this ologies. But there is more to this and civilization is in question, and idyllic scene comes a Coke bot film than meets the eye. ... a great where the humour is nonstop. tle thrown from a passing plane. deal more. Discord erupts among the happy First, there is the incredibly These are the images packaged folk as they strive to possess the patronizing attitude towards the in Jamie Uys' hit film, The Gods bottle. Clearly heaven has made Bushmen, or San as I prefer to Must Be Crazy now playing to ca a mistake (hence the film's title) pacity audiences around the world. call them. The Bushman as Noble Savage is a peculiar piece of white South Africa's previous suc South African racial mythology. In cesses in international film distri the popular press the Bushman are bution have served their racism a favorite weekend magazine topic. -

In Search of a National Cinema in South Africa

Isabel Balseiro, Ntongela Masilela, eds.. To Change Reels: Film and Film Culture in South Africa. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2003. 272 pp. $39.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-8143-3000-5. Reviewed by Peter Davis Published on H-SAfrica (February, 2004) Against the Odds: In Search of a National Cin‐ imbedded in all areas of flm production and dis‐ ema In South Africa tribution as South Africa. But this statement To Change Reels, edited by Isabel Balseiro and comes with the caveat that what we are talking Ntongela Masilela, looks at South African cinema about is the politics of exclusion. This was the from almost the earliest times up to the present. great paradox: that cinema, the most popular art South Africa early on developed a flm industry, form to evolve during the twentieth century, be‐ but for a number of reasons was limited in its haved in South Africa as if 75 percent of the popu‐ scope by restrictions that were partly self-im‐ lation did not exist. In no other country that as‐ posed. So South African cinema in its entirety is pired to a national cinema did this happen: Amer‐ not a large body of work, but while most of it can‐ ican, British, French, German, Indian, Japanese, not lay claim to the upper reaches of cinematic and Swedish cinemas all built on a solid domestic achievement, almost everything produced re‐ base. Even tiny Denmark did the same, and for wards study, from early epic to flms made for much of the silent period at least, was a world cin‐ miners to the ethnic pulp movies of the 1970s and ema. -

Imaging Africa: Gorillas, Actors and Characters

Imaging Africa: Gorillas, Actors And Characters Africa is defined in the popular imagination by images of wild animals, savage dancing, witchcraft, the Noble Savage, and the Great White Hunter. These images typify the majority of Western and even some South African film fare on Africa. Although there was much negative representation in these films I will discuss how films set in Africa provided opportunities for black American actors to redefine the way that Africans are imaged in international cinema. I conclude this essay with a discussion of the process of revitalisation of South African cinema after apartheid. The study of post-apartheid cinema requires a revisionist history that brings us back to pre-apartheid periods, as argued by Isabel Balseiro and Ntongela Masilela (2003) in their book’s title, To Change Reels. The reel that needs changing is the one that most of us were using until Masilela’s New African Movement interventions (2000a/b;2003). This historical recovery has nothing to do with Afrocentricism, essentialism or African nationalisms. Rather, it involved the identification of neglected areas of analysis of how blacks themselves engaged, used and subverted film culture as South Africa lurched towards modernity at the turn of the century. Names already familiar to scholars in early South African history not surprisingly recur in this recovery, Solomon T. Plaatje being the most notable. It is incorrect that ‘modernity denies history, as the contrast with the past – a constantly changing entity – remains a necessary point of reference’ (Outhwaite 2003: 404). Similarly, Masilela’s (2002b: 232) notion thatconsciousness ‘ of precedent has become very nearly the condition and definition of major artistic works’ calls for a reflection on past intellectual movements in South Africa for a democratic modernity after apartheid. -

Ways of Seeing (In) African Cinema Panel: Selected Filmography 1 The

Ways of Seeing (in) African Cinema panel: Selected Filmography The Higher Learning staff curate the digital resource packages to complement and offer further context to the topics and themes discussed during the various Higher Learning events held at TIFF Bell Lightbox. These filmographies, bibliographies, and additional resources include works directly related to the guests’ career and event’s themes, as well as works that, while seemingly unrelated, were discussed during the event as jumping off points for further research. Please refer to the event video to see how all topics and themes relate to the Higher Learning event. *mentioned or discussed during the panel Sub-Saharan African Feature Films Black Girl. Dir. Ousmane Sembène, 1965, Senegal. 60 mins. Production Co. Les Actualities Françaises / Films Domirev. Mandabi. Dir. Ousmane Sembène, 1968, France and Senegal. 90 mins. Production Co.: Comptoir Français du Film Production (CFFP) / Filmi Domirev. Le Wazzou Polygame. Dir. Oumarou Ganda, 1970, Niger. 50 mins. Production Co.: unknown. Emitaï. Dir. Ousmane Sembène, 1971, Senegal. 101 mins. Production Co.: Metro Pictures. Sambizanga. Dir. Sarah Maldoror, 1972, Angola. 102 mins. Production Co.: unknown. Touki Bouki. Dir. Djibril Diop Mambéty, 1973, Senegal. 85 mins. Production Co.: unknown. Harvest: 3000 Years. Dir. Haile Gerima, 1975, Ethiopia. 150 mins. Production Co.: Mypheduh Films, Inc. Kaddu Beykat. Dir. Safi Faye, 1975, Senegal. 95 mins. Production Co.: Safi Production. Xala. Dir. Ousmane Sembène, 1975, Senegal. 123 mins. Production Co.: Films Domireew / Ste. Me. Production du Senegal. Ceddo. Dir. Ousmane Sembène, 1977, Senegal. 120 mins. Production Co.: unknown. The Gods Must Be Crazy. Dir. Jamie Uys, 1980, Namibia. -

Let's Break with Apartheid!

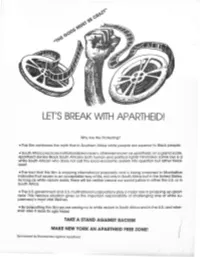

LET'S BREAK WITH APARTHEID! Why Are We Protesting? • This film reinforces the myth that in Southern Africa white people are superior to Black people. • .South Africa practices institutionalized raCism, otherwise known as apartheid, on a grand scale. Apartheid denies Black South Africans both human and political rights! Filmmaker Jamie Uys is a white South African who does not call this socio-economic system into question but rather trivial izes it. • The fact that this film is enjoying international popularity and is being screened in Manhattan indicates that racism is an acceptable way of life, not only in South Africa but in the United States. As long as white racism exists, there will be neither peace nor social justice in either the U.S. or in South Africa. •The U.S. government and U.S. multinational corporations play a major role in propping up apart heid. This heinous situation gives us the important responsibility of challenging one of white su premacy's most. vital lifelines . • By b6~otting this film we are saying no to white racism in South Africa and in the U.S. and wher ever else it rears its ugly head. TAKE A STAND AGAINST RACISM MAKE NEW YORK AN APARTHEID FREE ZONE! Sponsored by Brooklynites Against Apartheid I MAKING FILMS FOR APARTHEID IS GETTING TO BE A HABIT, LET'S BREAK IT ... "The Gods Must Be Crazy" has receive~d rave reviews as a "comedy". Do you know what you're being csked to laugh at? The San people (a Black nation otherwise known as Bushmen), about whom this film is made, are one .of the oldest civiliz.ations on earth. -

Botswana Cinema Studies View Metadata, Citation and Similar Papers at Core.Ac.Uk Brought to You by CORE

Botswana Cinema Studies http://www.thuto.org/ubh/cinema/bots-cinema-studies.htm View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt am Main BOTSWANA CINEMA & FILM STUDIES 1st Edition by Neil Parsons © March 2004 Note to BMS 103 & GEC 362 students: You are welcome to download and photocopy parts of this file for private study purposes, on condition you do not sell BOTSWANA CINEMA & FILM STUDIES 1st Edition or any part of it to any individual or company. A hardcopy will be found in the Reserve section of the University of Botswana Library. Copyright enquiries should be sent to <nparsons> at the address <@mopipi.ub.bw>. Contents 1: Introduction 2: The First Fifty Years 1896-1947 3: The Locust Years 1948-1965 4: Botswana Independence 1966-1980 5: Under Attack 1981-1993 6: The Last Ten Years 1994-2004 Appendix: ‘The Kanye Cinema Experiment of 1944-1946’ (separate web page) [Back to contents] 1. Introduction Cinema studies are a new but not infertile field for Botswana. A major work on African cinema, Africa on Film: Beyond Black and White by Kenneth M. Cameron (New York: Continuum Publishing, 1994), was actually written in Gaborone while the author’s wife was on a one-year attachment with the University of Botswana English Department. A recent and certainly incomplete film and videography of Botswana and the Kalahari lists almost five hundred titles of feature films and documentaries (relatively few), ethnographic and wildlife films (many), and newsreel clips (numerous) since 1906-07. -

Inventory of the Private Collection of M Viljoen PV14

Inventory of the private collection of M Viljoen PV14 Contact us Write to: Visit us: Archive for Contemporary Affairs Archive for Contemporary Affairs University of the Free State Stef Coetzee Building P.O. Box 2320 Room 109 Bloemfontein 9300 Academic Avenue South South Africa University of the Free State 205 Nelson Mandela Drive Park West Bloemfontein Telephone: Email: +27(0)51 401 2418/2646/2225 [email protected] PV14 M Viljoen, M (Marais) FILE NO SERIES SUB-SERIES DESCRIPTION DATES 1/1/1/ 1. AGENDAS, 1/1 General No File; This series also consist of MINUTES AND correspondence, reports etc. DECISIONS 1/2/1/ 1. AGENDAS, 1/2 National Party: Minutes and reports: Minutes of meeting of the 1968 - 1972* MINUTES AND Federal Council Federal Council of the National Party Cape DECISIONS Town 17 May 1968; Minutes meeting of the Federal Council of the National Party Cape Town 29 May 1969; Minutes meeting of the Federal Council of the National Party Cape Town 27 May 1971; Minutes meeting of the Federal Council of the National Party Cape Town 20 August 1971; Minutes meeting of the Federal Council of the National Party Cape Town 2 June 1972. 1/3/1/ 1. AGENDAS, 1/3 National Party: Agendas and Minutes: Minutes Special 1967 - 1973* MINUTES AND Information Service meeting Information Committee of the National DECISIONS Party Pretoria 25 September 1967; Minutes Special meeting Information Committee of the National Party Cape Town 5 February 1968; Agenda Federal Information Service 16 July 1973. 1/4/1/ 1. AGENDAS, 1/4 National Party of Agendas, Minutes, etc.: Agenda National Party 1957 - 1962* MINUTES AND Transvaal of Transvaal annual congress 17 -19 DECISIONS September 1957; Agenda Meeting management of the National Party of Transvaal Pretoria 12 November 1958; Agenda meeting of the National Party of Transvaal Pretoria 12 November 1958; Minutes meeting National Party of Transvaal Pretoria 14 November 1960; Minutes meeting of the National Party of Transvaal Cape Town 10 June 1961. -

W W W. S a F U N D I . C

The Journal of South African and American Comparative Studies ISSUE 3 OCTOBER 2000 A CONFUSION OF CINEMATIC CONSCIOUSNESS SOUTHERN AFRICA ON FILM IN THE UNITED STATES Keyan Tomaselli University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban Arnold Shepperson University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban www.safundi.com A Confusion of Cinematic Consciousness SOUTHERN AFRICA ON FILM IN THE UNITED STATES Keyan Tomaselli University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban Arnold Shepperson University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban any documentary films available for teaching purposes in the United States were made prior to President F. W. de Klerk’s dramatic political reforms begun in MFebruary 1990. This month marked the unbanning of all liberation movements, both internal and exiled, including the Communist Party. The films made prior to 1990, then, refer to apartheid in the present tense, and often encode the despair of ever being able to defeat this iniquitous system. However, films made after 1990 begin to reveal the difficulties, but also the possibilities that emerged as South Africans of all constituencies negotiated their way towards a democratic future. In this study I review films made up to 1990, largely evaluated by a team consisting of African (especially southern African) specialists with expertise in a variety of disciplines: media, film, television, cultural studies, politics, language studies, speech, anthropology, history, education, literature, sociology, development, health, and agriculture. The team included a number of Africans, southern Africans, and Americans.1 1. The project in 1990/1991 was coordinated by Keyan G. Tomaselli, Visiting Research Scholar, and Maureen Eke (Nigeria), Coordinator, African Outreach Center, under the auspices of the African Media Center, a division of the African Studies Center (ASC), Michigan State University (MSU), East Lansing between August 1990 and January 1992. -

Anthropology and the Bushman Anthro & Bushman 4/3/07 9:18 Am Page Ii Anthro & Bushman 4/3/07 9:18 Am Page Iii

Anthro & Bushman 4/3/07 9:18 am Page i Anthropology and the Bushman Anthro & Bushman 4/3/07 9:18 am Page ii Anthro & Bushman 4/3/07 9:18 am Page iii Anthropology and the Bushman Alan Barnard Oxford • New York Anthro & Bushman 4/3/07 9:18 am Page iv First published in 2007 by Berg Editorial offices: 1st Floor, Angel Court, 81 St Clements Street, Oxford, OX4 1AW, UK 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA © Alan Barnard 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of Berg. Berg is the imprint of Oxford International Publishers Ltd. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Barnard, Alan (Alan J.) Anthropology and the bushman / Alan Barnard. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-84520-428-0 (cloth) ISBN-10: 1-84520-428-X (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-1-84520-429-7 (pbk.) ISBN-10: 1-84520-429-8 (pbk.) 1. San (African people)—Kalahari Desert—Social life and customs. 2. Ethnology—Kalahari Desert—Field work. 3. Anthropology in popular culture—Kalahari Desert. 4. Kalahari Desert—Social life and customs. I. Title. DT1058.S36B35 2007 305.896’1—dc22 2006101698 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 1 84520 428 0 (Cloth) ISBN 978 1 84520 429 7 (Paper) Typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed in the United Kingdom by Biddles Ltd, King’s Lynn www.bergpublishers.com Anthro & Bushman -

![Onderwerp: [SA-Gen] Bundel Nommer 1470](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4352/onderwerp-sa-gen-bundel-nommer-1470-8474352.webp)

Onderwerp: [SA-Gen] Bundel Nommer 1470

Augustus 2007 Bundels Onderwerp: [SA-Gen] Bundel Nommer 2845 Datum: Wed Aug 1, 2007 Daar is 9 boodskappe in hierdie uitgawe Onderwerpe in hierdie bundel: 1. Rebellie 1914 en SWA From: Hetta Scholtz 2a. Pretoria Argiewe From: Annelie Els 3a. Janse van Rensburg navorsing From: Annelie Els 4a. Re: plaasgeskiedenisse / aktes From: Ursulah 4b. Re: plaasgeskiedenisse / aktes From: Charl van Tonder 5. (Koerant) Beeld 01 Aug. 2007 From: Fanie Blignaut 6a. Re: Jamie Uys From: Willeen Olivier 6b. Re: Jamie Uys From: Annemarie van den Doel 7. RE [SA-Gen] Jamie Uys en sy gesin From: Johann De Bruin Boodskap 1. Rebellie 1914 en SWA Posted by: "Hetta Scholtz" [email protected] hester_scholtz Tue Jul 31, 2007 6:12 pm (PST) Lyslede, Hier is 'n webwerfmet name van al die ongevalle tydens die Rebellie 1914 en die oorlog met Duitsland in SWA(Namibië) http://www.geocities.com/Heartland/Ridge/2216/text/SA1914.TXT Groete Hetta Scholtz, Rooihuiskraal Boodskap 2a. Pretoria Argiewe Posted by: "Annelie Els" [email protected] engelkind2000 Tue Jul 31, 2007 8:38 pm (PST) Hallo Jacques, Die Argief is glad nie meer op `n Saterdag oop nie. Groetnis Annelie Valhalla Boodskap 3a. Janse van Rensburg navorsing Posted by: "Annelie Els" [email protected] engelkind2000 Tue Jul 31, 2007 9:13 pm (PST) More Medegeners veral die RENSBURG mense, Skies dat ek nou eers antwoord, was van Donderdag laas week tot en met gisteraand laat in Durban gewees. Ek was laas Maandag by Emmerentia aan huis gewees. Sy vertrek, of het reeds, vir 3 maande na haar dogter oorsee. -

DOCUMENT RESUME AUTHOR Quest of Visual Literacy: Deconstructing Visual Images of 10P.; In: Visionquest: Journeys Toward Visual L

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 408 975 IR 018 388 AUTHOR Semali, Ladislaus TITLE Quest of Visual Literacy: Deconstructing Visual Images of Indigenous People. PUB DATE Jan 97 NOTE 10p.; In: VisionQuest: Journeys toward Visual Literacy. Selected Readings from the Annual Conference of the International Visual Literacy Association (28th, Cheyenne, Wyoming, October, 1996); see IR 018 353. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative (142) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Critical Thinking; *Critical Viewing; *Cultural Images; Ethnic Groups; Film Criticism; *Films; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Indigenous Populations; Inquiry; Misconceptions; *Visual Literacy; Visual Stimuli IDENTIFIERS *Africa (Sub Sahara); *Gods Must Be Crazy (The); Visual Representation ABSTRACT This paper introduces five concepts that guide teachers' and students' critical inquiry in the understanding of media and visual representation. In a step-by-step process, the paper illustrates how these five concepts can become a tool with which to critique and examine film images of indigenous people. The Sani are indigenous people of the Kalahari Desert in Southern Africa. The culture, language and social life of the Sani has been represented in the film, "The Gods Must Be Crazy" (1984). Through the humorous images in the film, the writer-director makes jokes about the absurdities and discontinuities of African life. In films, through the manipulation of camera angles and other techniques, the viewer is given a sense of realism. Such ploys of visual representations of people demand a careful analysis to discover:(1) what is at issue;(2) how the issue/event is defined;(3) who is involved;(4) what the arguments are; and (5) what is taken for granted, including cultural assumptions.