South African Cinema (1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissertation Terre Blanche Hj.Pdf

IDEOLOGIES AFFECTING UPPER AND MIDDLE CLASS AFRIKANER WOMEN IN JOHANNESBURG, 1948, 1949 AND 1958 by HELEN JENNIFER TERRE BLANCHE submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF A M GRUNDLINGH JOINT SUPERVISOR: DR D PRINSLOO NOVEMBER 1997 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to record my thanks to my supervisor and joint supervisor who generously gave of their time and knowledge. Prof Albert Grundlingh was unfailingly helpful and patient, and Dr Dione Prinsloo kindly allowed me to make use of interviews she had conducted. Her knowledge of the Afrikaner community in Johannesburg was also invaluable. I would also like to thank my family, my husband, for his comments and proofreading, my mother for the proofreading of the final manuscript, and my children, Sara and Ruth, for their patience and tolerance. I would also like to thank my father for encouraging my interest in history from an early age. Thanks are also due to Mrs Renee d'Oiiveira, headmistress of Loreto Convent, Skinner street, for her interest in my studies and her support. 305.483936068221 TERR UNISA BI8Lf0Tt:;~:: / LIBRARY Class Klas ... Access Aanwin ... 111111111111111 0001705414 Student number: 460-005-3 I declare that "Ideologies affecting upper and middle class Afrikaner women in Johannesburg, 1948, 1949 a.nd 1958" is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references . .. ;//.-.! ~~~a.~q~~ ......... SIGNATURE DATE (H J TERRE BLANCHE) SUMMARY This thesis investigates discourses surrounding upper and middle class Afrikaner women living in Johannesburg during the years 1948, 1949 and 1958. -

The Colonising Laughter in Mr.Bones and Sweet and Short

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE THE COLONISING LAUGHTER IN MR.BONES AND SWEET AND SHORT TSEPO MAMATU KGAFELA OA MAGOGODI supervisor A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Wits University, Johannesburg, 2006 1 ABSTRACT This research explores the element of the colonial laughter in Leon Schuster’s projects, Mr.Bones and Sweet and Short. I engage with the theories of progressive black scholars in discussing the way Schuster represents black people in these projects. I conclude by probing what the possibilities are in as far as rupturing the paradigms of negative imaging that Schuster, and those that support the idea of white supremacy through their projects, seek/s to normalise. 2 Declaration I declare that this dissertation/thesis is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Masters of the Arts in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination in any other university. TSEPO MAMATU 15 February 2006 3 Dedication We live for those who love us For those who love us true For the heaven that smiles above us and awaits our spirits For the cause that lacks resistance For the future in the distance And the good we must do! Yem-yem, sopitsho zibhentsil’intyatyambo. Mandixhole ngamaxhesha onke, ndizothin otherwise? 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Title page……………………………pg1 -

Crime, Violence and Apartheid in Selected Works of Richard Wright and Athol

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) Crime, violence and apartheid in selected works of Richard Wright and Athol Fugard: a study. Name: RODWELL MAKOMBE A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Literature and Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Studies at the University of Fort Hare Student Number: 200904755 Name of Institution: UNIVERSITY OF FORT HARE Supervisor: DR. M. BLATCHFORD Year: 2011 Contents DECLARATION .............................................................................................................. iii DEDICATION ..................................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... v ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................vi CHAPTER ONE .............................................................................................................. 1 Crime, violence and apartheid: the postcolonial/criminological approach .................... 1 Statement of the Problem ......................................................................................... 1 Background .............................................................................................................. 2 Aims of the research ................................................................................................ -

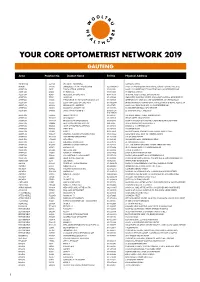

Your Core Optometrist Network 2019 Gauteng

YOUR CORE OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2019 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 9071046 SHOPS -

Memories of Johannesburg, City of Gold © Anne Lapedus

NB This is a WORD document, you are more than Welcome to forward it to anyone you wish, but please could you forward it by merely “attaching” it as a WORD document. Contact details For Anne Lapedus Brest [email protected] [email protected]. 011 783.2237 082 452 7166 cell DISCLAIMER. This article has been written from my memories of S.Africa from 48 years ago, and if A Shul, or Hotel, or a Club is not mentioned, it doesn’t mean that they didn’t exist, it means, simply, that I don’t remember them. I can’t add them in, either, because then the article would not be “My Memories” any more. MEMORIES OF JOHANNESBURG, CITY OF GOLD Written and Compiled By © ANNE LAPEDUS BREST 4th February 2009, Morningside, Sandton, S.Africa On the 4th February 1961, when I was 14 years old, and my brother Robert was 11, our family came to live in Jhb. We had left Ireland, land of our birth, leaving behind our beloved Grandparents, family, friends, and a very special and never-to-be-forgotten little furry friend, to start a new life in South Africa, land of Sunshine and Golden opportunity…………… The Goldeneh Medina…... We came out on the “Edinburgh Castle”, arriving Cape Town 2nd Feb 1961. We did a day tour of Chapmans Peak Drive, Muizenberg, went to somewhere called the “Red Sails” and visited our Sakinofsky/Yodaiken family in Tamboerskloof. We arrived at Park Station (4th Feb 1961), Jhb, hot and dishevelled after a nightmarish train ride, breaking down in De Aar and dying of heat. -

Umass Fine Arts Center Concert Hall

umassumass finefine artsarts center center CENTERCENTER SERIESSERIES 2008–20092008–2009 1 1 2 3 2 3 playbill playbill 1 Paul Taylor Dance Company 11/13/08 2 Avery Sharpe Trio 11/21/08 3 Soweto Gospel Choir 12/03/08 1 Paul Taylor Dance Company 11/13/08 2 Avery Sharpe Trio 11/21/08 3 Soweto Gospel Choir 12/03/08 UMA021-PlaybillCover.indd 3 8/6/08 11:03:54 PM UMA021-PlaybillCover.indd 3 8/6/08 11:03:54 PM DtCokeYoga8.5x11.qxp 5/17/07 11:30 AM Page 1 DC-07-M-3214 Yoga Class 8.5” x 11” YOGA CLASS ©2007The Coca-Cola Company. Diet Coke and the Dynamic Ribbon are registered trademarks The of Coca-Cola Company. 2 We’ve mastered the fine art of health care. Whether you need a family doctor or a physician specialist, in our region it’s Baystate Medical Practices that takes center stage in providing quality and excellence. From Greenfield to East Longmeadow, from young children to seniors, from coughs and colds to highly sophisticated surgery — we’ve got the talent and experience it takes to be the best. Visit us at www.baystatehealth.com/bmp 3 &ALLON¬#OMMUNITY¬(EALTH¬0LAN IS¬PROUD¬TO¬SPONSOR¬THE 5-ASS¬&RIENDS¬OF¬THE¬&INE¬!RTS¬#ENTER 4 5 Supporting The Community We Live In Helps Create a Better World For All Of Us Allen Davis, CFP® and The Davis Group Are Proud Supporters of the Fine Arts Center! The work we do with our clients enables them to share their assets with their families, loved ones, and the causes they support. -

ARCHIV-VERSION Dokserver Des Zentrums Für Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam E.V

ARCHIV-VERSION Dokserver des Zentrums für Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam e.V. http://zeitgeschichte-digital.de/Doks Katharina Fink Jürgen Schadeberg: Something you don’t see https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok.5.1212 Archiv-Version des ursprünglich auf dem Portal Visual-History am 03.07.2016 mit der URL: https://www.visual-history.de/2016/07/03/juergen-schadeberg-something-you-dont-see/ erschienenen Textes Copyright © 2018 Clio-online – Historisches Fachinformationssystem e.V. und Autor/in, alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist zum Download und zur Vervielfältigung für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke freigegeben. Es darf jedoch nur erneut veröffentlicht werden, sofern die Einwilligung der o.g. Rechteinhaber vorliegt. Dies betrifft auch die Übersetzungsrechte. Bitte kontaktieren Sie: <[email protected]> Für die Neuveröffentlichung von Bild-, Ton- und Filmmaterial, das in den Beiträgen enthalten ist, sind die dort jeweils genannten Lizenzbedingungen bzw. Rechteinhaber zu beachten. 1 von 6 Online-Nachschlagewerk für VISUALHISTORY die historische Bildforschung 3. Juli 2016 Katharina Fink Thema: Fotografen Rubrik: Akteure JÜRGEN SCHADEBERG: SOMETHING YOU DON’T SEE Jürgen Schadeberg: Nelson Mandela’s return to his cell on Robben Island IV, 1994 © Jürgen Schadeberg mit freundlicher Genehmigung Eines seiner wohl berühmtesten Bilder ist zur Ikone geworden – zu einem jener Bilder, in denen Vergangenheit und Zukunft ineinander fallen: der gealterte Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, der mit tiefen Falten und ergrautem Haar aus dem mit massiven Gitterstäben versehenen Fenster schaut. Den rechten Ellenbogen hat Mandela auf die Fensterbank gelegt, auf seiner linken Brusttasche fällt ein Emblem ins Auge. Das Bild ist 1994 entstanden. Offiziell ist Südafrika ein freies Land, und Mandela ist für das Foto in die Zelle auf Robben Island zurückgekehrt, in der er 18 seiner insgesamt 27 Jahre in Haft verbrachte. -

The Gods Must Be Crazy but the Producers Know Exactly What They Are Doing

_ _ _____ _ _ o _ The Gods Must Be Crazy But the producers know exactly what they are doing BY RICHARD B. LEE The film opens with a highly Both viewers and reviewers are Richard Lee is a Toronto-based anthro romanticized ethnography of the taken in by the charm and inno pologist who has worked with the San primitive Bushmen in their remote cence of the Gods ... especially the for over twenty years. home in "Botswana", (Actually sympathetic portrayal of the non Welcome to Apartheid funland, the film was shot in Namibia). whites. The clever sight gags evoke where white and black mingle eas The voice-over extols the virtues laughter that ignores political ide ily, where the savages are noble of their simple life. Into this ologies. But there is more to this and civilization is in question, and idyllic scene comes a Coke bot film than meets the eye. ... a great where the humour is nonstop. tle thrown from a passing plane. deal more. Discord erupts among the happy First, there is the incredibly These are the images packaged folk as they strive to possess the patronizing attitude towards the in Jamie Uys' hit film, The Gods bottle. Clearly heaven has made Bushmen, or San as I prefer to Must Be Crazy now playing to ca a mistake (hence the film's title) pacity audiences around the world. call them. The Bushman as Noble Savage is a peculiar piece of white South Africa's previous suc South African racial mythology. In cesses in international film distri the popular press the Bushman are bution have served their racism a favorite weekend magazine topic. -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

334 Chapter 10 Natal Afrikaner Women and The

University of Pretoria etd – Wassermann, J M (2005) 334 CHAPTER 10 NATAL AFRIKANER WOMEN AND THE ANGLO-BOER WAR The role and plight of the Republican Afrikaner women have always formed an integral, and sometimes even central part of the historiography of the Anglo-Boer War. The emphasis in the large number of academic and popular works and published memoirs invariably falls on the suffering of Afrikaner women and children in the concentration camps. Despite this volume of work, Helen Bradford1 maintains that one of the seminal questions faced by the historiography of the Anglo-Boer War is the neglect of the unique war experiences of women. One group previously neglected was Natal Afrikaner women who formed a stratified and diverse group. Some, like MJ Zietsman of Snelster near Estcourt, whose daughter, the widow Wallace had been to England and who kept thoroughbred Pointers, were wealthy and sophisticated.2 Another, like ME Kock, read Tennyson and Shakespeare,3 while Emily Pieters owned 20 bound music books for playing the piano and harmonium.4 On the other end of the social scale were women like Annie Katrina Slabbert of Dundee who sewed and took in laundry to survive.5 These class differences were underpinned by the patriarchal system in which the women functioned. Married women had the least power and received little support or recognition from the authorities. In contrast widows wielded much more economic and political power and were also able to generate letters and other documents.6 However, regardless of their educational, social, economic or marital status, most Natal Afrikaner women suffered, in one way or another, during the war. -

South Africa and Russia (1890–2010)

Viewing ‘the other’ over a hundred and a score more years: South Africa and Russia (1890–2010) I LIEBENBERG* Abstract Whether novel is history or history is novel, is a tantalising point. “The novel is no longer a work, a thing to make last, to connect the past with the future but (only) one current event among many, a gesture with no tomorrow” Kundera (1988:19). One does not have to agree with Kundera to find that social sciences, as historiography holds a story, a human narrative to be shared when focused on a case or cases. In this case, relations between peoples over more than a century are discussed. At the same time, what is known as broader casing in qualitative studies enters the picture. The relations between the governments and the peoples of South Africa and Russia (including the Soviet Union), sometimes in conflict or peace and sometimes at variance are discussed. Past and present communalities and differences between two national entities within a changing international or global context deserve attention while moments of auto-ethnography compliment the study. References are made to the international political economy in the context of the relations between these countries. Keywords: Soviet Union, South Africa, Total Onslaught, United Party, Friends of the Soviet Union, ideological conflict (South Africa), Russians (and the Anglo-Boer War), racial capitalism, apartheid, communism/Trotskyism (in South Africa), broader casing (qualitative research) Subject fields: political science, sociology, (military) history, international political economy, social anthropology, international relations, conflict studies Introduction The abstract above calls up the importance of “‘transnational’ and ‘transboundary’ theories and perspectives” and the relevance of the statement that, Worldwide, the rigid boundaries that once separated disciplines have become less circumscribed; they are no longer judged by the static conventions of yesteryear (Editorial, Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 2009: iii-iv). -

"Master Harold"

Hally, we’re bumping into each other all the time. Look at the three of us this afternoon: I’ve bumped into you, you’ve bumped into your mother, she bumping into your Dad... None of us knows the steps and there’s no music playing. And it doesn’t stop with us. The whole world is doing it all the time. -Sam, “MASTER HAROLD”...and the boys 1 STUDY GUIDE CONTRIBUTERS Elizabeth Dudgeon Libby Ford Hallie Gordon Elizabeth Levy Teachers and students can download additional copies of this study guide for free at www.steppenwolf.org. 2 Table of Contents The World of "MASTER HAROLD" …and the boys Plot Summary Character Analysis Themes of the Play Apartheid Laws Enacted in the Time of the Play Hally's Hometown: Port Elizabeth, South Africa Education in South Africa in the 1950's Vocabulary Playwright Athol Fugard Biography of Athol Fugard Fugard Responds to Apartheid South African Responses to Apartheid Activism and The Artist: Using Art to Speak Out against Apartheid TIMELINE: The World of South Africa after MASTER HAROLD 1960-1991 Nelson Mandela: His Activism and Leadership A Global Response to Apartheid Connections: The Civil Rights Movement in the United States The End of Apartheid The World's Cultural and Political Boycott of South Africa The Rise of AIDS Truth and Reconciliation Commission Today in Chicago The Steppenwolf Production An Interview with the Director, K.Todd Freeman Design Elements 3 Apartheid was a system of laws put in place by the white-minority government in South Africa. It enforced discrimination and segregation of the black and “Coloured” (mixed race) majority, denying them their basic civil and legal rights.