Kent Gij Dat Volk: the Anglo-Boer War and Afrikaner Identity in Postmodern Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of the Witwatersrand

UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND AFRICAN STUDIES INSTITUTE African Studies Seminar Paper to be presented in RW 4.00pm MARCH 1984 Title: The Case Against the Mfecane. by: Julian Cobbing No. 144 UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND AFRICAN STUDIES INSTITUTE African studies Seminar Paper to be presented at Seminar in RW 319 at 4,00 pm on Monday, 5 March 1984 THE CASE AGAINST THE MFECANE by. QuJJjun Cobbing. By the 1970s the mfecane had become one of the most widely abused terms in southern African historical literature. Let the reader attempt a simple definition of the mfecane, for instance. This is not such an easy task. From one angle the mfecane was the Nguni diaspora which from the early 1820s took Nguni raiding communities such as the Ndebele, the Ngoni and the Gaza over a huge region of south-central Africa reaching as far north as Lake Tanzania. Africanists stress the positive features of the movement. As Ajayi observed in 1968: 'When we consider all the implications of the expansions of Bantu-speaking peoples there can he no doubt that the theory of stagnation has no basis whatsoever.' A closely related, though different, mfecane centres on Zululand and the figure of Shaka. It has become a revolutionary process internal to Nguni society which leads to the development of the ibutho and the tributary mode of production. Shaka is a heroic figure providing a positive historical example and some self-respect for black South Africans today. But inside these wider definitions another mfecane more specific- ally referring to the impact of Nguni raiders (the Nedbele, Hlubi and Ngwane) on the Sotho west of the Drakensberg. -

Dissertation Terre Blanche Hj.Pdf

IDEOLOGIES AFFECTING UPPER AND MIDDLE CLASS AFRIKANER WOMEN IN JOHANNESBURG, 1948, 1949 AND 1958 by HELEN JENNIFER TERRE BLANCHE submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF A M GRUNDLINGH JOINT SUPERVISOR: DR D PRINSLOO NOVEMBER 1997 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to record my thanks to my supervisor and joint supervisor who generously gave of their time and knowledge. Prof Albert Grundlingh was unfailingly helpful and patient, and Dr Dione Prinsloo kindly allowed me to make use of interviews she had conducted. Her knowledge of the Afrikaner community in Johannesburg was also invaluable. I would also like to thank my family, my husband, for his comments and proofreading, my mother for the proofreading of the final manuscript, and my children, Sara and Ruth, for their patience and tolerance. I would also like to thank my father for encouraging my interest in history from an early age. Thanks are also due to Mrs Renee d'Oiiveira, headmistress of Loreto Convent, Skinner street, for her interest in my studies and her support. 305.483936068221 TERR UNISA BI8Lf0Tt:;~:: / LIBRARY Class Klas ... Access Aanwin ... 111111111111111 0001705414 Student number: 460-005-3 I declare that "Ideologies affecting upper and middle class Afrikaner women in Johannesburg, 1948, 1949 a.nd 1958" is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references . .. ;//.-.! ~~~a.~q~~ ......... SIGNATURE DATE (H J TERRE BLANCHE) SUMMARY This thesis investigates discourses surrounding upper and middle class Afrikaner women living in Johannesburg during the years 1948, 1949 and 1958. -

Journal of Southern African Studies 'A Boer and His Gun and His Wife

This article was downloaded by: [University of Stellenbosch] On: 7 March 2011 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 921023904] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Southern African Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713436095 'A boer and his gun and his wife are three things always together': republican masculinity and the 1914 rebellion Sandra Swarta a Magdalen College, University of Oxford, To cite this Article Swart, Sandra(1998) ''A boer and his gun and his wife are three things always together': republican masculinity and the 1914 rebellion', Journal of Southern African Studies, 24: 4, 737 — 751 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/03057079808708599 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03057079808708599 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

The Debate on the Mfecane That Erupted Following the Publication In

A TEMPEST IN A TEAPOT? NINETEENTH-CENTURY CONTESTS FOR LAND IN SOUTH AFRICA‘S CALEDON VALLEY AND THE INVENTION OF THE MFECANE ABSTRACT: The unresolved debate on the mfecane in Southern African history has been marked by general acceptance of the proposition that large scale loss of life and disruption of settled society was experienced across the whole region. Attempts to quantify either the violence or mortality have been stymied by a lack of evidence. What apparently reliable evidence does exist describes small districts, most notably the Caledon Valley. In contrast to Julian Cobbing, who called the mfecane an alibi for colonial-sponsored violence, this article argues that much documentation of conflict in the Caledon region consisted of various ‗alibis‘ for African land seizures and claims in the 1840s and ‗50s. KEY WORDS: pre-colonial, mfecane, Lesotho, South Africa, nineteenth- century, warfare, land A hotly contested issue in the debate on South Africa‘s mfecane which enlivened the pages of this journal a decade ago was the charge that colonial historians invented the concept as part of a continuing campaign to absolve settler capitalism from responsibility for violent convulsions in South- 1 Eastern Africa in the first half of the nineteenth century.i This article takes a different tack by arguing that African struggles for land and power in the period 1833-54 played a decisive role in developing the mfecane concept. The self-serving narratives devised by African rivals and their missionary clients in and around the emerging kingdom of Lesotho set the pattern for future accounts and were responsible for introducing the word lifaqane into historical discourse long before the word mfecane first appeared in print. -

Early History of South Africa

THE EARLY HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES . .3 SOUTH AFRICA: THE EARLY INHABITANTS . .5 THE KHOISAN . .6 The San (Bushmen) . .6 The Khoikhoi (Hottentots) . .8 BLACK SETTLEMENT . .9 THE NGUNI . .9 The Xhosa . .10 The Zulu . .11 The Ndebele . .12 The Swazi . .13 THE SOTHO . .13 The Western Sotho . .14 The Southern Sotho . .14 The Northern Sotho (Bapedi) . .14 THE VENDA . .15 THE MASHANGANA-TSONGA . .15 THE MFECANE/DIFAQANE (Total war) Dingiswayo . .16 Shaka . .16 Dingane . .18 Mzilikazi . .19 Soshangane . .20 Mmantatise . .21 Sikonyela . .21 Moshweshwe . .22 Consequences of the Mfecane/Difaqane . .23 Page 1 EUROPEAN INTERESTS The Portuguese . .24 The British . .24 The Dutch . .25 The French . .25 THE SLAVES . .22 THE TREKBOERS (MIGRATING FARMERS) . .27 EUROPEAN OCCUPATIONS OF THE CAPE British Occupation (1795 - 1803) . .29 Batavian rule 1803 - 1806 . .29 Second British Occupation: 1806 . .31 British Governors . .32 Slagtersnek Rebellion . .32 The British Settlers 1820 . .32 THE GREAT TREK Causes of the Great Trek . .34 Different Trek groups . .35 Trichardt and Van Rensburg . .35 Andries Hendrik Potgieter . .35 Gerrit Maritz . .36 Piet Retief . .36 Piet Uys . .36 Voortrekkers in Zululand and Natal . .37 Voortrekker settlement in the Transvaal . .38 Voortrekker settlement in the Orange Free State . .39 THE DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS AND GOLD . .41 Page 2 EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES Humankind had its earliest origins in Africa The introduction of iron changed the African and the story of life in South Africa has continent irrevocably and was a large step proven to be a micro-study of life on the forwards in the development of the people. -

A Brief History of Wine in South Africa Stefan K

European Review - Fall 2014 (in press) A brief history of wine in South Africa Stefan K. Estreicher Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409-1051, USA Vitis vinifera was first planted in South Africa by the Dutchman Jan van Riebeeck in 1655. The first wine farms, in which the French Huguenots participated – were land grants given by another Dutchman, Simon Van der Stel. He also established (for himself) the Constantia estate. The Constantia wine later became one of the most celebrated wines in the world. The decline of the South African wine industry in the late 1800’s was caused by the combination of natural disasters (mildew, phylloxera) and the consequences of wars and political events in Europe. Despite the reorganization imposed by the KWV cooperative, recovery was slow because of the embargo against the Apartheid regime. Since the 1990s, a large number of new wineries – often, small family operations – have been created. South African wines are now available in many markets. Some of these wines can compete with the best in the world. Stefan K. Estreicher received his PhD in Physics from the University of Zürich. He is currently Paul Whitfield Horn Professor in the Physics Department at Texas Tech University. His biography can be found at http://jupiter.phys.ttu.edu/stefanke. One of his hobbies is the history of wine. He published ‘A Brief History of Wine in Spain’ (European Review 21 (2), 209-239, 2013) and ‘Wine, from Neolithic Times to the 21st Century’ (Algora, New York, 2006). The earliest evidence of wine on the African continent comes from Abydos in Southern Egypt. -

“Men of Influence”– the Ontology of Leadership in the 1914 Boer

Journal of Historical Sociology Vol. 17 No. 1 March 2004 ISSN 0952-1909 “Men of Influence” – The Ontology of Leadership in the 1914 Boer Rebellion SANDRA SWART Abstract This paper raises questions about the ontology of the Afrikaner leader- ship in the 1914 Boer Rebellion – and the tendency to portray the rebel leadership in terms of monolithic Republicans, followed by those who shared their dedication to returning the state to the old Boer republics. Discussions of the Rebellion have not focused on the interaction between leadership and rank and file, which in part has been obscured by Republican mythology based on the egalitarianism of the Boer commando. This paper attempts to establish the ambitions of the leaders for going into rebellion and the motivations of those who followed them. It traces the political and economic changes that came with union and industrialization, and asks why some influential men felt increasingly alienated from the new form of state structure while others adapted to it. To ascertain the nature of the support for the leaders, the discussion looks at Republican hierarchy and the ideology of patri- archy. The paper further discusses the circumscribed but significant role of women in the Rebellion. This article seeks to contribute to a wider understanding of the history of leadership in South Africa, entangled in the identity dynamics of mas- culinity, class and race interests. ***** Man, I can guess at nothing. Each man must think for himself. For myself, I will go where my General goes. Japie Krynauw (rebel).1 In 1914 there was a rebellion against the young South African state. -

The German Colonization of Southwest Africa and the Anglo-German Rivalry, 1883-1915

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 7-1-1995 Doors left open then slammed shut: The German colonization of Southwest Africa and the Anglo-German rivalry, 1883-1915 Matthew Erin Plowman University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Plowman, Matthew Erin, "Doors left open then slammed shut: The German colonization of Southwest Africa and the Anglo-German rivalry, 1883-1915" (1995). Student Work. 435. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/435 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOORS LEFT OPEN THEN SLAMMED SHUT: THE GERMAN COLONIZATION OF SOUTHWEST AFRICA AND THE ANGLO-GERMAN RIVALRY, 1883-1915. A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts University of Nebraska at Omaha by Matthew Erin Plowman July 1995 UMI Number: EP73073 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Blsaartalibn Publish*rig UMI EP73073 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

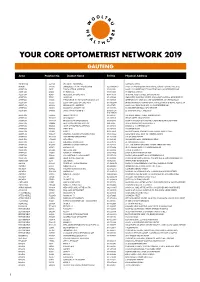

Your Core Optometrist Network 2019 Gauteng

YOUR CORE OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2019 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 9071046 SHOPS -

History 1886

How many bones must you bury before you can call yourself an African? Updated December 2009 A South African Diary: Contested Identity, My Family - Our Story Part D: 1886 - 1909 Compiled by: Dr. Anthony Turton [email protected] Caution in the use and interpretation of these data This document consists of events data presented in chronological order. It is designed to give the reader an insight into the complex drivers at work over time, by showing how many events were occurring simultaneously. It is also designed to guide future research by serious scholars, who would verify all data independently as a matter of sound scholarship and never accept this as being valid in its own right. Read together, they indicate a trend, whereas read in isolation, they become sterile facts devoid of much meaning. Given that they are “facts”, their origin is generally not cited, as a fact belongs to nobody. On occasion where an interpretation is made, then the commentator’s name is cited as appropriate. Where similar information is shown for different dates, it is because some confusion exists on the exact detail of that event, so the reader must use caution when interpreting it, because a “fact” is something over which no alternate interpretation can be given. These events data are considered by the author to be relevant, based on his professional experience as a trained researcher. Own judgement must be used at all times . All users are urged to verify these data independently. The individual selection of data also represents the author’s bias, so the dataset must not be regarded as being complete. -

Chapter IV Events During the Transitional Phase

University of Pretoria etd - McLeod AJ (2004) Chapter IV Events during the transitional phase 1. Introduction When General Piet Cronjé capitulated on 27 February 1900 at Paardeberg, with the result that 4 091 people were taken prisoner by the British, it could well have been the final act in the Anglo-Boer War, for it must have been clear, even at such an early stage of the war, that Lord Roberts’ march to the two republican capitals would be unrelenting and could not be stopped. This was confirmed by a burgher of Heilbron, Cornelis van den Heever, who stated in an interview in 1962 : “Want voor ons hier weg is [na Brandwaterkom toe] kon jy vir ’n donkie vra of ons die oorlog sal wen en hy sou sy ore geskud het. Want dit was ’n hopelose ding nadat Blo[e]mfontein en Pretoria ingeneem is en die Engelse by duisende en derduisende ingekom het.”1 The war could at best be prolonged in the hope that some other solution could be reached. The British superiority in numbers and war equipment could not be equalled by the Boers. However, the war did not end after Paardeberg, nor did it end when Bloemfontein was occupied on 13 March 1900, or even when Pretoria fell on 5 June of the same year. It continued for another two years and three months after Cronjé’s surrender. It is well known that the continued conflict changed its form from conventional warfare to guerrilla warfare. Although this transformation did not take place overnight, it meant that in future the war would influence the lives of many more people than it had done before. -

The Construction of Eugène Marais As an Afrikaner Hero*

The Construction of Eugène Marais as an Afrikaner Hero* SANDRA SWART (Stellenbosch University) Eugène Marais (1871–1936) is remembered as an Afrikaner hero. There are, however, competing claims as to the meaning of this ‘heroic’ status. Some remember him as the ‘father of Afrikaans poetry’, one of the most lionised writers in Afrikaans and part of the Afrikaner nationalist movement. Yet a second intellectual tradition remembers him as a dissident iconoclast, an Afrikaner rebel. This article seeks to show, first, how these two very different understandings of Marais came to exist, and, secondly, that the course of this rivalry of legends was inextricably bound up with the socio-economic and political history of South Africa. We look at his portrayal at particular historical moments and analyse the changes that have occurred with reference to broader developments in South Africa. This is in order to understand the making of cultural identity as part of nationalism, and opens a window onto the contested process of re-imagining the Afrikaner nation. The article demonstrates how Marais’s changing image was a result of material changes within the socio-economic milieu, and the mutable needs of the Afrikaner establishment. The hagiography of Marais by the Nationalist press, both during his life and after his death, is explored, showing how the socio-political context of the Afrikaans language struggle was influential in shaping his image. The chronology of his representation is traced in terms of the changing self-image of the Afrikaner over the ensuing seven decades. Finally, in order to understand the fractured meaning of Marais today, the need for alternative heroes in the ‘New South Africa’ is considered.