Beating Around the Bushmen a Controversy Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gods Must Be Crazy but the Producers Know Exactly What They Are Doing

_ _ _____ _ _ o _ The Gods Must Be Crazy But the producers know exactly what they are doing BY RICHARD B. LEE The film opens with a highly Both viewers and reviewers are Richard Lee is a Toronto-based anthro romanticized ethnography of the taken in by the charm and inno pologist who has worked with the San primitive Bushmen in their remote cence of the Gods ... especially the for over twenty years. home in "Botswana", (Actually sympathetic portrayal of the non Welcome to Apartheid funland, the film was shot in Namibia). whites. The clever sight gags evoke where white and black mingle eas The voice-over extols the virtues laughter that ignores political ide ily, where the savages are noble of their simple life. Into this ologies. But there is more to this and civilization is in question, and idyllic scene comes a Coke bot film than meets the eye. ... a great where the humour is nonstop. tle thrown from a passing plane. deal more. Discord erupts among the happy First, there is the incredibly These are the images packaged folk as they strive to possess the patronizing attitude towards the in Jamie Uys' hit film, The Gods bottle. Clearly heaven has made Bushmen, or San as I prefer to Must Be Crazy now playing to ca a mistake (hence the film's title) pacity audiences around the world. call them. The Bushman as Noble Savage is a peculiar piece of white South Africa's previous suc South African racial mythology. In cesses in international film distri the popular press the Bushman are bution have served their racism a favorite weekend magazine topic. -

Programming Ideas

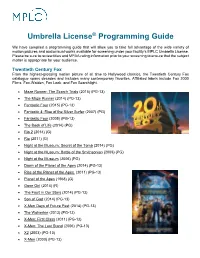

Umbrella License® Programming Guide We have compiled a programming guide that will allow you to take full advantage of the wide variety of motion pictures and audiovisual works available for screening under your facility’s MPLC Umbrella License. Please be sure to review titles and MPAA rating information prior to your screening to ensure that the subject matter is appropriate for your audience. Twentieth Century Fox From the highest-grossing motion picture of all time to Hollywood classics, the Twentieth Century Fox catalogue spans decades and includes many contemporary favorites. Affiliated labels include Fox 2000 Films, Fox-Walden, Fox Look, and Fox Searchlight. • Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials (2015) (PG-13) • The Maze Runner (2014) (PG-13) • Fantastic Four (2015) (PG-13) • Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007) (PG) • Fantastic Four (2005) (PG-13) • The Book of Life (2014) (PG) • Rio 2 (2014) (G) • Rio (2011) (G) • Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014) (PG) • Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009) (PG) • Night at the Museum (2006) (PG) • Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) (PG-13) • Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) (PG-13) • Planet of the Apes (1968) (G) • Gone Girl (2014) (R) • The Fault in Our Stars (2014) (PG-13) • Son of God (2014) (PG-13) • X-Men Days of Future Past (2014) (PG-13) • The Wolverine (2013) (PG-13) • X-Men: First Class (2011) (PG-13) • X-Men: The Last Stand (2006) (PG-13) • X2 (2003) (PG-13) • X-Men (2000) (PG-13) • 12 Years a Slave (2013) (R) • A Good Day to Die Hard (2013) -

God Must Be Crazy 3 Download

1 / 4 God Must Be Crazy 3 Download QUOTE(amir.asyraf @ Feb 21 2020, 06:24 PM). damn it can't find any torrent for it :( *. If you're looking for Gods must be crazy , i can download .... Find the perfect the gods must be crazy stock photo. Huge collection, amazing choice, 100+ million high quality, affordable RF and RM images. No need to .... The Gods Must Be Crazy Collection chronicles the comic adventures of a Kalahari Bushman named Xixo as his world is invaded by modern civilisation.. Download film god must be crazy 3. The gods must be crazy 3 youtube. The gods must be crazy wikipedia. The gods must be crazy 1980 trailer | n! Xau | marius .... Top 10 Latest English Audio Mp3 Song Free Download : 1 1 Shake It Off ... Bass Meghan Trainor 3 3 Bang Ban Download backing music in midi and CD formats. ... (かくし付き) Download Mp3 Chris Brown Young Thug Go Crazy Instrumental, ... Our goal is to create products that make it easier to perform and mix using all .... the gods must be crazy hindi dubbed, the gods must be crazy hindi dubbed movie download, the gods mu.. I saw The Gods Must Be Crazy back in the 1980s at the Somerville Theatre in Massachussetts, about ... Click here to download the KTabS file. the gods must be crazy 3 tamil dubbed movie download, the gods must be crazy tamil dubbed movie down.. 6 I can't seem to download with mIRC; 7 mIRC XDCC Scripts; 8 XDCC Search ... full moviethe god must be crazy movie free downloadgod must be crazy 3 full ... -

The Varsity Theater: a Case Study of the One-Screen Locally-Owned Movie Theater Business in Iowa

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2012 The aV rsity Theater: A case study of the one-screen locally-owned movie theater business in Iowa Mohammad Sadegh Foghani Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Foghani, Mohammad Sadegh, "The aV rsity Theater: A case study of the one-screen locally-owned movie theater business in Iowa" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12322. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12322 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Varsity Theater: A case study of the one-screen locally-owned movie theater business in Iowa By Mohammad Sadegh Foghani A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Program of Study Committee: Amy Bix, Major Professor Charles M. Dobbs Leland A. Poague Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 Copyright © Mohammad Sadegh Foghani, 2012. All rights reserved. ii Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction .............................................................................................1 1.1. The Nickelodeons and the Prestigious Movie Palaces ..........................................1 1.2. The Art Deco Style, Drive-Ins and First Multiplexes............................................5 1.3. Multiplexes Become Dominant ......................................................................... -

Journal for Academic Excellence

1 June 2016 Volume 4, Issue 5 Journal for Academic Excellence Proceedings Edition of the Seventh Annual Dalton State College Center for Academic Teaching and Learning Conference Excellence Dalton State College A Division of the Office of Dalton State College Faculty Accomplishments Academic Affairs The mission of the CAE is Page 2 to facilitate, support, and enhance the teaching and learning process at Dalton State College. The Center Electronic Rubrics for Evaluating Student Oral Presentations serves to ultimately improve student success Christine Jonick and Jennifer Schneider and achievement of learning outcomes by University of North Georgia promoting the creation of Page 5 effective learning environments through the provision of resources and Engaging Students Through Cinematic Experiences of Diversity and faculty development opportunities. Global Learning Ray-Lynn Snowden University of North Georgia Page 9 Integrating the Capstone Experience: From Negotiations to Grants Bagie M. George Georgia Gwinnett College Page 19 2 Faculty and Staff Accomplishments Ms. Anne Loughren, Ms. Tracey May, Interim Dr. Ronda Ford, adjunct Assistant Director of Campus Coordinator of the Gilmer instructor of flute at Dalton Recreation, Fitness Programs, Campus, graduated from the State College, will be going on a graduated from Georgia Leadership Gilmer class on ten-day tour to Japan with the College and State University May 3. It was a nine-month International Flute Orchestra with a Master of Science in program through the Gilmer during the last two weeks of Health & Human Performance County Chamber of Commerce May. The flute orchestra will with a concentration in Health that involved participants’ perform concerts in Osaka, Promotion. -

Botswana Cinema Studies View Metadata, Citation and Similar Papers at Core.Ac.Uk Brought to You by CORE

Botswana Cinema Studies http://www.thuto.org/ubh/cinema/bots-cinema-studies.htm View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt am Main BOTSWANA CINEMA & FILM STUDIES 1st Edition by Neil Parsons © March 2004 Note to BMS 103 & GEC 362 students: You are welcome to download and photocopy parts of this file for private study purposes, on condition you do not sell BOTSWANA CINEMA & FILM STUDIES 1st Edition or any part of it to any individual or company. A hardcopy will be found in the Reserve section of the University of Botswana Library. Copyright enquiries should be sent to <nparsons> at the address <@mopipi.ub.bw>. Contents 1: Introduction 2: The First Fifty Years 1896-1947 3: The Locust Years 1948-1965 4: Botswana Independence 1966-1980 5: Under Attack 1981-1993 6: The Last Ten Years 1994-2004 Appendix: ‘The Kanye Cinema Experiment of 1944-1946’ (separate web page) [Back to contents] 1. Introduction Cinema studies are a new but not infertile field for Botswana. A major work on African cinema, Africa on Film: Beyond Black and White by Kenneth M. Cameron (New York: Continuum Publishing, 1994), was actually written in Gaborone while the author’s wife was on a one-year attachment with the University of Botswana English Department. A recent and certainly incomplete film and videography of Botswana and the Kalahari lists almost five hundred titles of feature films and documentaries (relatively few), ethnographic and wildlife films (many), and newsreel clips (numerous) since 1906-07. -

W W W. S a F U N D I . C

The Journal of South African and American Comparative Studies ISSUE 3 OCTOBER 2000 A CONFUSION OF CINEMATIC CONSCIOUSNESS SOUTHERN AFRICA ON FILM IN THE UNITED STATES Keyan Tomaselli University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban Arnold Shepperson University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban www.safundi.com A Confusion of Cinematic Consciousness SOUTHERN AFRICA ON FILM IN THE UNITED STATES Keyan Tomaselli University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban Arnold Shepperson University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban any documentary films available for teaching purposes in the United States were made prior to President F. W. de Klerk’s dramatic political reforms begun in MFebruary 1990. This month marked the unbanning of all liberation movements, both internal and exiled, including the Communist Party. The films made prior to 1990, then, refer to apartheid in the present tense, and often encode the despair of ever being able to defeat this iniquitous system. However, films made after 1990 begin to reveal the difficulties, but also the possibilities that emerged as South Africans of all constituencies negotiated their way towards a democratic future. In this study I review films made up to 1990, largely evaluated by a team consisting of African (especially southern African) specialists with expertise in a variety of disciplines: media, film, television, cultural studies, politics, language studies, speech, anthropology, history, education, literature, sociology, development, health, and agriculture. The team included a number of Africans, southern Africans, and Americans.1 1. The project in 1990/1991 was coordinated by Keyan G. Tomaselli, Visiting Research Scholar, and Maureen Eke (Nigeria), Coordinator, African Outreach Center, under the auspices of the African Media Center, a division of the African Studies Center (ASC), Michigan State University (MSU), East Lansing between August 1990 and January 1992. -

Anthropology and the Bushman Anthro & Bushman 4/3/07 9:18 Am Page Ii Anthro & Bushman 4/3/07 9:18 Am Page Iii

Anthro & Bushman 4/3/07 9:18 am Page i Anthropology and the Bushman Anthro & Bushman 4/3/07 9:18 am Page ii Anthro & Bushman 4/3/07 9:18 am Page iii Anthropology and the Bushman Alan Barnard Oxford • New York Anthro & Bushman 4/3/07 9:18 am Page iv First published in 2007 by Berg Editorial offices: 1st Floor, Angel Court, 81 St Clements Street, Oxford, OX4 1AW, UK 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA © Alan Barnard 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of Berg. Berg is the imprint of Oxford International Publishers Ltd. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Barnard, Alan (Alan J.) Anthropology and the bushman / Alan Barnard. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-84520-428-0 (cloth) ISBN-10: 1-84520-428-X (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-1-84520-429-7 (pbk.) ISBN-10: 1-84520-429-8 (pbk.) 1. San (African people)—Kalahari Desert—Social life and customs. 2. Ethnology—Kalahari Desert—Field work. 3. Anthropology in popular culture—Kalahari Desert. 4. Kalahari Desert—Social life and customs. I. Title. DT1058.S36B35 2007 305.896’1—dc22 2006101698 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 1 84520 428 0 (Cloth) ISBN 978 1 84520 429 7 (Paper) Typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed in the United Kingdom by Biddles Ltd, King’s Lynn www.bergpublishers.com Anthro & Bushman -

Wilmington University Library DVD Holdings List

Wilmington University Library DVD Holdings List DVD 1 The Men Who Killed Kennedy: the Definitive Account of American History's Most Controversial Mystery, 1988 / Nigel Turner Productions; History Channel Location: New Castle DVD 2 Image of an Assassination: a New Look at the Zapruder film, 1998 Location: New Castle DVD 3 Bull Durham, 1988 Location: New Castle DVD 4 National Lampoon's Animal House, 1978 / Universal Pictures Location: Missing DVD 5 Punch-Drunk Love, 2002 / Revolution Studios; New Line Cinema Location: New Castle DVD 6 Adaptation, 2003 / Columbia Pictures Location: New Castle DVD 7 The Hours, 2003 / Paramount Pictures and Miramax Films Location: New Castle DVD 8 Once Upon a Time in America, 1984 / Embassy International Pictures Location: New Castle DVD 9 Bowling for Columbine, 2002 / United Artists and Alliance Atlantis Location: New Castle DVD 10 Pianist, 2002 Location: New Castle DVD 11 xXx, 2002 / Revolution Studios Location: Missing DVD 12 Remains of the day, 1993 / Columbia Pictures Location: New Castle DVD 13 New York in the Fifties, 2001 / First Run Features Location: New Castle DVD 14 The Adventure of Photography: 150 years of the photographic image, 1998 / Cromwell Productions Location: New Castle DVD 15 Tai Chi for Arthritis, 2002 / East Acton Videos Location: New Castle DVD 16 War in Iraq: the road to Baghdad, 2003 / CNN; Time Inc. Home Entertainment. Location: New Castle (2); Dover DVD 17 Gangs of New York, 2002 / Miramax Films Location: Missing DVD 18 Old School, 2003 / DreamWorks Pictures Location: New Castle -

Surveying the Gods Must Be Crazy Through a Post- and Neo-Colonial Telescope

Public Journal of Semiotics 6 (2) “He wants to know how all those people got in there”: Surveying The Gods Must Be Crazy through a post- and neo-colonial telescope Roie Thomas The popular film The Gods Must Be Crazy (1980) remains, despite its age, the primary reference point for Westerners with regard to the San people of southern Africa (commonly known outside Africa as the Bushmen). It is a catalyst for tourist interest in the people since many tourists, as this paper demonstrates, credulously accept the mythology that the San people live now as (and where) they do in the film. Indeed, a Lonely Planet ‘coffee-table’ publication of 2010 cites the film as mandatory viewing for tourists prior to visiting Botswana. The San’s lifestyle is depicted in the film as one of Garden-of-Eden tranquility, although the landscape is somewhat more arid than the Genesis idyll. The San had been driven out of the Kalahari by the Botswana government in the interests of diamond mining, big-game hunting and high-end tourism. Meanwhile, tourist ephemera in-country extols the lifestyle of the Bushmen esoterically, producing imagery that suggests they are still living as they did for millennia, omitting any mention of their modern realities and perpetuating a lie about their ongoing relationship with lands to which they no longer have access. The film is explored here via some thematic distinctions of Spurr (1993). This paper transcribes these distinctions (or tropes) of colonialist thought and action as neo-colonialist which are ubiquitously in operation within the modern tourism industry, perpetuating disempowerment to a significant extent. -

DOCUMENT RESUME AUTHOR Quest of Visual Literacy: Deconstructing Visual Images of 10P.; In: Visionquest: Journeys Toward Visual L

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 408 975 IR 018 388 AUTHOR Semali, Ladislaus TITLE Quest of Visual Literacy: Deconstructing Visual Images of Indigenous People. PUB DATE Jan 97 NOTE 10p.; In: VisionQuest: Journeys toward Visual Literacy. Selected Readings from the Annual Conference of the International Visual Literacy Association (28th, Cheyenne, Wyoming, October, 1996); see IR 018 353. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative (142) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Critical Thinking; *Critical Viewing; *Cultural Images; Ethnic Groups; Film Criticism; *Films; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Indigenous Populations; Inquiry; Misconceptions; *Visual Literacy; Visual Stimuli IDENTIFIERS *Africa (Sub Sahara); *Gods Must Be Crazy (The); Visual Representation ABSTRACT This paper introduces five concepts that guide teachers' and students' critical inquiry in the understanding of media and visual representation. In a step-by-step process, the paper illustrates how these five concepts can become a tool with which to critique and examine film images of indigenous people. The Sani are indigenous people of the Kalahari Desert in Southern Africa. The culture, language and social life of the Sani has been represented in the film, "The Gods Must Be Crazy" (1984). Through the humorous images in the film, the writer-director makes jokes about the absurdities and discontinuities of African life. In films, through the manipulation of camera angles and other techniques, the viewer is given a sense of realism. Such ploys of visual representations of people demand a careful analysis to discover:(1) what is at issue;(2) how the issue/event is defined;(3) who is involved;(4) what the arguments are; and (5) what is taken for granted, including cultural assumptions. -

PRIMITIVISM and CONTEMPORARY POPULAR CINEMA by STEVEN

PRIMITIVISM AND CONTEMPORARY POPULAR CINEMA by STEVEN DAVID NORTON A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2015 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Steven David Norton Title: Primitivism and Contemporary Popular Cinema This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of English by: Sangita Gopal Chair Michael Aronson Core Member Kirby Brown Core Member Michael Allan Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2015. ii © 2015 Steven David Norton iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Steven David Norton Doctor of Philosophy Department of English September 2015 Title: Primitivism and Contemporary Popular Cinema This dissertation is a postcolonial analysis of four films: The Gods Must Be Crazy (1980), Dances with Wolves (1990), The Last Samurai (2003), and Avatar (2009). While previous scholarship has identified the Eurocentric worldview of early 20th-century ethnographic film, no book-length work has analyzed the time consciousness of turn-of- the-21st century films that feature portrayals of the colonial encounter. By harmonizing film theory with postcolonial theory, this dissertation explores how contemporary films reiterate colonial models of time in ways which validate colonial aggression. This dissertation concludes that the aesthetics of contemporary popular cinema collude with colonial models of time in such a way as to privilege whiteness vis-à-vis constructions of a primitive other.