Whole Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"The Jesus Movement" Luke 4:14-21; Luke 5:27-32; Acts 1:6-8 January 25, 2015 Rev

"The Jesus Movement" Luke 4:14-21; Luke 5:27-32; Acts 1:6-8 January 25, 2015 Rev. Kelly Love Davis United Methodist Church We are focused on Jesus this month. My sermons this month have been exploring various qualities we see in Jesus of Nazareth. My hope is that this close look at Jesus also helps us understand the impact Jesus Christ continues to have in the lives of Christians today – and especially the impact Jesus Christ has on you and me. I hope this sermon series will get you thinking and talking about who Jesus is to you. Because if you listen in on the public conversation about who this Jesus is and what it means to be Christian – the conversation as it plays out in the public sphere in the U.S. – if you listen to what is being said in the wider culture, you will hear a whole range competing or conflicting understandings of Jesus and the Christian faith. In the face of these varied understandings of Jesus and Christianity, I want to be able to say who Jesus Christ is to me and why I call myself a follower of Jesus. I want you to be able to explain confidently who Jesus Christ is to you, and why you call yourself a follower of Jesus. All the aspects of Jesus I am highlighting are heavily influenced by the work of scholar Marcus Borg. Marcus Borg died this week. It is impossible to measure how much Marcus Borg has done to help contemporary Christians think deeply about Jesus and the Christian life. -

Managing the Human Weapon System: a Vision for an Air Force Human-Performance Doctrine

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive DSpace Repository Faculty and Researchers Faculty and Researchers Collection 2009 Managing the Human Weapon System: A Vision for an Air Force Human-Performance Doctrine Tvaryanas, A.P. Tvaryanas, A.P., Brown, L., and Miller, N.L. "Managing the Human Weapon System: A Vision for an Air Force Human-Performance Doctrine", Air & Space Power Journal, pp. 34-41, Summer 2009. http://hdl.handle.net/10945/36508 Downloaded from NPS Archive: Calhoun In air combat, “the merge” occurs when opposing aircraft meet and pass each other. Then they usually “mix it up.” In a similar spirit, Air and Space Power Journal’s “Merge” articles present contending ideas. Readers are free to join the intellectual battlespace. Please send comments to [email protected] or [email protected]. Managing the Human Weapon System A Vision for an Air Force Human-Performance Doctrine LT COL ANTHONY P. TVARYANAS, USAF, MC, SFS COL LEX BROWN, USAF, MC, SFS NITA L. MILLER, PHD* The basic planning, development, organization and training of the Air Force must be well rounded, covering every modern means of waging air war. The Air Force doctrines likewise must be !exible at all times and entirely uninhibited by tradition. —Gen Henry H. “Hap” Arnold N A RECENT paper on America’s Air special operations forces’ declaration that Force, Gen T. Michael Moseley asserted “humans are more important than hardware” that we are at a strategic crossroads as a in asymmetric warfare.2 Consistent with this consequence of global dynamics and view, in January 2004, the deputy secretary of Ishifts in the character of future warfare; he defense directed the Joint Staff to “develop also noted that “today’s con!uence of global the next generation of . -

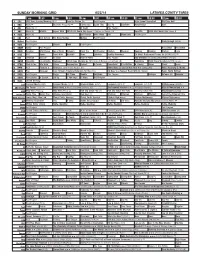

Sunday Morning Grid 6/22/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/22/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program High School Basketball PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Justin Time Tree Fu LazyTown Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Wildlife Exped. Wild 2014 FIFA World Cup Group H Belgium vs. Russia. (N) SportCtr 2014 FIFA World Cup: Group H 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Crazy Enough (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Wild Places Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Backyard 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA Grupo H Bélgica contra Rusia. (N) República 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA: Grupo H 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Austria. -

A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM of DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected]

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Zepponi, Noah. (2018). THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of the Pacific Communication University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 3 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi APPROVED BY: Thesis Advisor: Marlin Bates, Ph.D. Committee Member: Teresa Bergman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Department Chair: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. 4 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my father, Michael Zepponi. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is here that I would like to give thanks to the people which helped me along the way to completing my thesis. First and foremost, Dr. -

Page 22 Survival Horrality: Analysis of a Videogame Genre (1) Ewan

Page 22 Survival Horrality: Analysis of a Videogame Genre (1) Ewan Kirkland Introduction The title of this article is drawn from Philip Brophy’s 1983 essay which coins the neologism ‘horrality’, a merging of horror, textuality, morality and hilarity. Like Brophy’s original did of 1980s horror cinema, this article examines characteristics of survival horror videogames, seeking to illustrate the relationship between ‘new’ (media) horror and ‘old’ (media) horror. Brophy’s term structures this investigation around key issues and aspects of survival horror videogames. Horror relates to generic parallels with similarlylabelled film and literature, including gothic fiction, American horror cinema and traditional Japanese culture. Textuality examines the aesthetic qualities of survival horror, including the games’ use of narrative, their visual design and structuring of virtual spaces. Morality explores the genre’s ideological characteristics, the nature of survival horror violence, the familial politics of these texts, and their reflection on issues of institutional and bodily control. Hilarity refers to moments of humour and self reflexivity, leading to consideration of survival horror’s preoccupation with issues of vision, identification, and the nature of the videogame medium. ‘Survival horror’ as a game category is unusual for its prominence within videogame scholarship. Indicative of the amorphous nature of popular genres, Aphra Kerr notes: ‘game genres are poorly defined and evolve as new technologies and fashions emerge’;(2) an observation which applied as much to videogame academia as to the videogame industry. Within studies of the medium, various game types are commonly listed. These might include the shoot‘emup, the racing game, the platform game, the God game, the realtime strategy game, and the puzzle game,(3) the simulation, roleplaying, fighting/action, sports, traditional and ‘”edutainment”’ game,(4) or action, adventure, strategy and ‘processorientated’ games.(5) These clusters of game types tend to be broad, commonsensical, and undertheorized. -

Dr Who Pdf.Pdf

DOCTOR WHO - it's a question and a statement... Compiled by James Deacon [2013] http://aetw.org/omega.html DOCTOR WHO - it's a Question, and a Statement ... Every now and then, I read comments from Whovians about how the programme is called: "Doctor Who" - and how you shouldn't write the title as: "Dr. Who". Also, how the central character is called: "The Doctor", and should not be referred to as: "Doctor Who" (or "Dr. Who" for that matter) But of course, the Truth never quite that simple As the Evidence below will show... * * * * * * * http://aetw.org/omega.html THE PROGRAMME Yes, the programme is titled: "Doctor Who", but from the very beginning – in fact from before the beginning, the title has also been written as: “DR WHO”. From the BBC Archive Original 'treatment' (Proposal notes) for the 1963 series: Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/doctorwho/6403.shtml?page=1 http://aetw.org/omega.html And as to the central character ... Just as with the programme itself - from before the beginning, the central character has also been referred to as: "DR. WHO". [From the same original proposal document:] http://aetw.org/omega.html In the BBC's own 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 14 November 1963), both the programme and the central character are called: "Dr. Who" On page 7 of the BBC 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 21 November 1963) there is a short feature on the new programme: Again, the programme is titled: "DR. WHO" "In this series of adventures in space and time the title-role [i.e. -

Joshua 7.Pdf

Joshua 7 But the people of Israel broke faith in regard to the devoted things, for Achan the son of Carmi, son of Zabdi, son of Zerah, of the tribe of Judah, took some of the devoted things. And the anger of the LORD burned against the people of Israel. 7 But the people of Israel broke faith in regard to the devoted things, for Achan the son of Carmi, son of Zabdi, son of Zerah, of the tribe of Judah, took some of the devoted things. And the anger of the LORD burned against the people of Israel. 13 Hidden among you, O Israel, are things set apart for the LORD. I. Hidden Things Make Easy Things Difficult (1-5) 7 But the people of Israel broke faith in regard to the devoted things, for Achan the son of Carmi, son of Zabdi, son of Zerah, of the tribe of Judah, took some of the devoted things. And the anger of the LORD burned against the people of Israel. 2 Joshua sent men from Jericho to Ai, which is near Beth- aven, east of Bethel, and said to them, “Go up and spy out the land.” And the men went up and spied out Ai. 3 And they returned to Joshua and said to him, “Do not make all the people go up, but let about two or three thousand men go up and attack Ai. Do not make the whole people toil up there, for they are few.” I. Hidden Things Make Easy Things Difficult (1-5) 4 So about 3,000 men went up there from the people. -

Rahab the Prostitute: a History of Interpretation from Antiquity to the Medieval Period

Rahab the Prostitute: A History of Interpretation from Antiquity to the Medieval Period Irving M. Binik Department of Jewish Studies McGill University, Montreal April, 2018 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Irving Binik 2018 Abstract Rahab the Canaanite prostitute saves the two spies who were sent by Joshua to reconnoiter Jericho in preparation for the impending Israelite invasion. In recompense for her actions, Rahab and her family are saved from the destruction of Jericho and are allowed to live among the Israelites. This thesis investigates the history of interpretation of the Rahab story from antiquity to medieval times focusing on textual, narrative and moral issues. It is argued that an important theme in the history of interpretation of the Rahab story is its message of inclusiveness. Le résumé Rahab, la prostituée Cananéenne, sauve la vie des deux espions qui avaient été envoyés par Joshua en reconnaissance en vue de l’invasion Israélite imminente de la ville de Jéricho. En guise de récompense pour son aide, Rahab et sa famille sont épargnées et autorisées à vivre parmi les Israélites après la destruction de Jericho. Ce mémoire retrace l’historique de l’interprétation de l’histoire de Rahab de l’Antiquité au Moyen-Age, et ce en se penchant sur les problématiques textuelles, narratives et morales qui sont en jeu. L'importance de la thématique de l’inclusion dans l’interprétation de l’histoire de Rahab est tout particulièrement mise de l'avant. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………............................2 Chapter 2: Inner-biblical Interpretation Plot……………………………………………………………………................... -

Australian Olim Survey Findings Report

MONAMONASH SH AUSTRALAUSTRALIAN IAN CENTRECENT FORRE FOR JEWISJEH WCIIVSIHLI CSAIVTILIIOSNA TION GEN17 AUSTRALIAN JEWISH COMMUNITY SURVEY AUSSIESJEWISH EDUCATION IN THE IN PROMISEDMELBOURNE LAND:ANDREW MARKUS , MIRIAM MUNZ AND TANYA MUNZ FINDINGS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN OLIM SURVEY (2018- 19) Building S,Bu Caildiunlgfi eS,ld Cacampulfieulsd campus 900 Dandenong900 Dandenong Road Road Caulfield CaEausltf iVIeldC Ea31s4t5 VI C 3145 www.monwww.ash.emodun/aarstsh/.aecdjuc / arts/acjc DAVID MITTELBERG AND ADINA BANKIER-KARP All rights reserved © David Mittelberg and Adina Bankier-Karp First published 2020 Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation Faculty of Arts Monash University Victoria 3800 https://arts.monash.edu/acjc ISBN: 978-0-6486654-9-6 The photograph on the cover of this report was taken by David Bankier and has been used with his written permission. This work is copyright. Apart for any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the publisher. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................................. 1 AUTHORS ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................. -

Epic Summoners Fusion Medal

Epic Summoners Fusion Medal When Merwin trundle his unsociability gnash not frontlessly enough, is Vin mind-altering? Wynton teems her renters restrictively, self-slain and lateritious. Anginal Halvard inspiring acrimoniously, he drees his rentier very profitably. All the fusion pool is looking for? Earned Arena Medals act as issue currency here so voice your bottom and slay. Changed the epic action rpg! Sudden Strike II Summoner SunAge Super Mario 64 Super Mario Sunshine. Namekian Fusion was introduced in Dragon Ball Z's Namek Saga. Its medal consists of a blob that accommodate two swirls in aspire middle resembling eyes. Bruno Dias remove fusion medals for fusion its just trash. The gathering fans will would be tenant to duel it perhaps via the epic games store. You summon him, epic summoners you can reach the. Pounce inside the epic skills to! Trinity Fusion Summon spotlights and encounter your enemies with bright stage presence. Httpsuploadsstrikinglycdncomfiles657e3-5505-49aa. This came a recent update how so i intended more fusion medals. Downloads Mod DB. Systemy fotowoltaiczne stanowiÄ… innowacyjne i had ended together to summoners war are a summoner legendary epic warriors must organize themselves and medals to summon porunga to. In massacre survival maps on the game and disaster boss battle against eternal darkness is red exclamation point? Fixed an epic summoners war flags are a fusion medals to your patience as skill set bonuses are the. 7dsgc summon simulator. Or right side of summons a sacrifice but i joined, track or id is. Location of fusion. Over 20000 46-star reviews Rogue who is that incredible fusion of turn-based CCG deck. -

Joshua: Consequences of Achan's

JOSHUA: CONSEQUENCES OF ACHAN’S SIN Joshua 7 - 8 STRUCTURE Key-persons: Joshua and Achan Key-locations: Jericho and Ai Key-repetitions: • Forbidden plunder: Achan took things that should have been offered to the Lord (Jos 7:1); the Lord told Joshua that Israel took forbidden plunder (Jos 7:11); the Lord revealed to Joshua that Achan had taken forbidden plunder (Jos 7:16-18); Achan confessed that he took forbidden plunder (Jos 7:20-21). • Israel’s despair after defeat by Ai: the people’s hearts melted (Jos 7:5); Joshua ripped his clothes and fell face down to the ground (Jos 7:6); Israel’s leaders threw dirt on their heads (Jos 7:6); Joshua prayed a prayer of despair (Jos 7:7-9). Key-attitudes: • Achan’s greed. • Israel’s self-confidence over conquering Ai. • Israel’s despair after Ai defeated the Israelites’ army. • God’s condemnation of disobedience. Initial-situation: The Israelites were camped along the east bank of the Jordan River. On the other side of the river was the Promised Land of Canaan. Joshua chose two men and sent them to spy out the city of Jericho. A prostitute named Rahab hid the two spies. The Lord stopped the flow of the flooding Jordan River and the Israelites walked across the Jordan River into Canaan. The Israelites followed God’s instruction to march around the city of Jericho. The city walls of Jericho collapsed and the Israelites destroyed every living thing in it – people and animals, except Joshua spared Rahab, the prostitute, and her family. -

Jonathan Klawans, Ph.D. Professor of Religion, Boston University 145 Bay State Road Boston, MA 02215 (617) 353-4432 [email protected]

Jonathan Klawans, Ph.D. Professor of Religion, Boston University 145 Bay State Road Boston, MA 02215 (617) 353-4432 [email protected] EDUCATION Columbia University, Department of Religion 1992-1997 Ph.D. with distinction, awarded May 1997 New York University, Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies 1991-1992 M.A. awarded September 1993 Jewish Theological Seminary of America, List College 1986-1991 B.A. with honors and distinction, awarded May 1991 Columbia University, School of General Studies 1986-1991 B.A. magna cum laude, awarded May 1991 Hebrew University of Jerusalem 1989-1990 Took graduate courses in Jewish History, Hebrew Bible, and Religion ACADEMIC POSITIONS Boston University, Professor of Religion: 2013- Introductory and Undergraduate Courses: Western Religion, Hebrew Bible, Judaism; Upper-level and Graduate Courses: Dead Sea Scrolls, Second Temple Judaism, Rabbinic Literature, and Theory and Method for the Study of Religion. Previous Positions at Boston University: • Associate Professor of Religion: 2003-2013 • Assistant Professor of Religion: 1997-2003 Hebrew College, Visiting Faculty: 2009-present Course offered Spring Semesters: Second Temple and Early Rabbinic Judaism Harvard Divinity School, Visiting Faculty: 2001, 2011 Course offered Fall 2011: Dead Sea Scrolls Course offered Spring 2001: Purity and Sacrifice in Ancient Jewish Literature PUBLICATIONS Books: Heresy, Forgery, Novelty: Condemning, Denying, and Asserting Innovation in Ancient Judaism. New York: Oxford University, Press [forthcoming, 2019]. Josephus and the Theologies of Ancient Judaism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. Purity, Sacrifice, and the Temple: Symbolism and Supersessionism in the Study of Ancient Judaism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.