A PRAGMATIC POST-STRUCTURALIST ACCOUNT of OPPRESSION and RESISTANCE by Erin C. Tarver Di

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Word from Régine Chassagne at Montreal’S MTELUS*

Our Philosphy KANPE is a We give the poorest communities in the Central Plateau a voice so that they can express their own needs, priorities, and foundation that goals. Our role is to help these communities to be supported by Haitian organizations who bring the complementary skills, brings support to knowledge, tools, and training necessary to provide guidance some of the most on the path to autonomy. Our Approach vulnerable families Haiti is flled with people who have talents and skills in many areas. We work to fnd the best local Haitian organizations in Haiti to help them and talents who can support these communities in attaining their goals in health, nutrition, education, agriculture, entre- achieve fnancial preneurship, and leadership. As a foundation, we ensure that funds are properly distributed autonomy, so that and that projects are carried out with respect for the goals of the community and according to strict norms of good they can “stand up”. governance and transparency. 2 Where KANPE works Baille Tourible Port-au-Prince 3 Since 2011, using an integrated approach on a focused geographical area, KANPE and its partners in Haiti are able to obtain tangible, sustainable results. Health & Nutrition Agriculture • A medical clinic serving over 11,000 • Distribution of bean seeds to 250 residents. We recorded more than farmers. 43,800 visits since opening in 2011. • Distribution of nearly 3,300 farm • More than 1,700 cases of cholera animals. treated since 2011. • Production of 12,000 fruit and • More than 1,000 Malaria tests are forest seedlings (Reforestation performed each year. -

Annual-Report-2016-2.Pdf

KANPE enables the Our Philosophy most vulnerable The Haitian population, identifying and expressing their own needs, is at the heart of our work. In our Haitian communities role as change agents serving this population, our to achieve financial role is to work with local partners and put in place autonomy so that plans to support their initiatives. they can “stand up”. Our Approach We work with Haitian partner organizations with complementary expertise, each of which brings knowledge, tools, and training necessary to help guide these communities on the path towards autonomy. These organizations have extensive track records and hold a very high level of credibility in their respective fields. Jean-Étienne Pierre and Isaac Pierre, two young members of the marching band, learning their lessons. 2 Since 2010, with the support of local partners, KANPE’s work has yielded significant results in the following fields: Health Education • Support for a medical clinic serving over • Financial support to 13 schools 11,000 residents. of Baille Tourible. • More than 1,500 cases of cholera treated. • Construction of 2 permanent shelters to accommodate 2 small schools. • More than 1,120 malaria tests performed. • Teacher training. Housing Leadership • 550 family homes received materials to conduct renovations and construct latrines. • Creation of a marching band for 45 young students from Baille Tourible. • Distribution of a basic water purification system to each family participating in the • Summer camp for 70 teenagers which Integrated Program. included 10 days of workshops and discussions on subjects like deforestation, Agriculture illiteracy, teenage pregnancy, and youth flight from rural areas. • Distribution of 7,500 pounds of bean seeds to 250 farmers. -

THE HOWLING DAWG Recapping the Events of JULY 2017

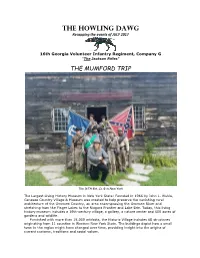

THE HOWLING DAWG Recapping the events of JULY 2017 16th Georgia Volunteer Infantry Regiment, Company G "The Jackson Rifles" THE MUMFORD TRIP The 16TH GA, Co. G in New York The Largest Living History Museum in New York State: Founded in 1966 by John L. Wehle, Genesee Country Village & Museum was created to help preserve the vanishing rural architecture of the Genesee Country, an area encompassing the Genesee River and stretching from the Finger Lakes to the Niagara Frontier and Lake Erie. Today, this living history museum includes a 19th-century village, a gallery, a nature center and 600 acres of gardens and wildlife. Furnished with more than 15,000 artifacts, the Historic Village includes 68 structures originating from 11 counties in Western New York State. The buildings depict how a small town in the region might have changed over time, providing insight into the origins of current customs, traditions and social values. As you stroll the village, you progress through three time periods … with lifestyles growing more sophisticated as time moves forward. In early 2017 an invitation was extended to the 16th GA, Co. G to come to Mumford and we are glad that a fine, representative group was able to go. The tales of the trip are best told in their own words: The Friday morning after we arrived at Mumford and set up camp, some of us went on a tour of the town with Seth. Seth was a friend of Charles and Brick from their Viking group and was quite knowledgeable about the town’s historic buildings and structures. -

NORTH DA/(I La! ::::> 2·Year Agreement • Section 8 (163 85) NE 1/4 Less RIW & Outlot 1 with Potential for Renewal • Section 9 (163 85) NW 1/4 Less RIW FOR

ICE dlllill UIIIIIIIIIII.llblll~iIIllllllll~I~__ :.Imll!IIH_ _ __ .IIIIIJIIU~l~lilllll~IOOI~~I.HI~!IIIUIWIII~I".111 Renville County Farmer Wednesday, February 17,2021 Page 8 Legals: Your Right to Know CITY OF GLENBURN FINANCIAL STATEMENT FOR 2020 366-6888 or 711; TTY, (800) 366-6889 Cash Balance Transfers Transfers Balance Notice to Creditors or 711; Voice, (800) 435-8590 or 71l. 11112020 Receipts In Out Disburse~ents 12/3112020 PROBATE NO. 38-2021-PR-00004 Alternative formats of the Action Plan General Fund ESTATE OF are available upon request. General Fund $ 711,968.85 $ 245,946.11 $ 7,144.45 $ 69,047.01 $ 232,592.00 $ 663,424.40 CYNTHIA L. McLAIN 19c Chelsey Dr. 2013 IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF Improvements 75,148.14 22,846.84 33,438.75 64,556.23 RENVILLE COUNTY, STATE OF Highwax Fund ~3.209.58 29,769.68 48,317.59 111.296.85 0.00 NORTH DAKOTA In the Matter of Mohall City Total AU Major the Estate of Cynthia L. McLain, De- REG ULAR MEETING OF THE Govnt. Funds $ 820.326.57 $ 298,562.63 $ 55,462.04 ($ 69,047.01) $377J27.~0 $ 727,980.63 ceased. MOHALL CITY COUNCIL NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN 2/8/2021 that the undersigned have been ap- City Council Rooms Non Major Funds: pointed personal representatives of the 7:00 p.m. Special Funds above estate. All persons having claims The meeting was called to order City Park $ 0.00 $ 0.00 $ 352.46 $ 352.46 $0.00 against the said deceased are required to with Mayor Witteman presiding. -

Sex and Gender Through an Analytic Eye: Butler on Freud and Gender Identity

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects Philosophy 2000 Sex and Gender Through an Analytic Eye: Butler on Freud and Gender Identity Anna Gullickson '00 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/phil_honproj Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Gullickson '00, Anna, "Sex and Gender Through an Analytic Eye: Butler on Freud and Gender Identity" (2000). Honors Projects. 7. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/phil_honproj/7 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. • SEX AND GENDER THROUGH AN ANALYTIC EYE: Butler on Freud and Gender Identity Anna Gullickson PHIL 381 Research Honors in Philosophy Illinois Wesleyan University Anna Gullickson 25 April 2000 SEX AND GENDER mROUGH AN ANALYTIC EYE: Butler on Freud and Gender Identity INTRODUCTION In her book. Gender Trouble, Judith Butler reinforces the conception held by many feminist philosophers that gender identity is not natural but rather culturally-constructed. Butler supports this conception ofgender mainly by reading (and misreading) Freud. -

Dialogues: the David Zwirner Podcast Marcel Dzama & Will Butler

Dialogues: The David Zwirner Podcast Marcel Dzama & Will Butler [SOUNDBITE; WILL BUTLER: Good afternoon, hello. MARCEL DZAMA: Thanks a lot. My name is Will Butler. I am a person who plays in a band called Arcade Fire and also does other music LZ: How did you guys first meet? I mean it was kind of and things like that. I live down in old Brooklyn your idea, Marcel, to set this up when we were talking. halfway to Coney Island. MARCEL DZAMA: I’m Marcel I was curious. WB: Oh, I see. Dzama. I’m an artist and I also live near Will.] MD: Let’s see, probably through Spike Jonze, I [MUSIC FADES IN] imagine. WB: I’m sure we just met at a show or something. LUCAS ZWIRNER: From David Zwirner, this is Dialogues—a podcast about creativity and ideas. MD: I think it was at Where the Wild Things Are opening. WB: Oh. [SOUNDBITE; MARCEL DZAMA: I listen to a lot of news and then that just finds its way into the drawings. MD: I think, if memory serves me right. I almost feel as an exorcism to get it out of me so I can go to sleep.] WB: Yeah, I think that’s actually right. We met at the premiere for Where the Wild Things Are at the Lincoln LZ: I’m Lucas Zwirner, Editorial Director of David Center. MD: The New York premiere. Zwirner Books. In every episode on the podcast we’ll introduce you to a surprising pairing. We’re taking LZ: Will, when did you get into music? Did you grow the artists we work with at the gallery and putting up playing instruments? Is your family musical? How them in conversation with some of the world’s most did those interests come about? extraordinary makers and thinkers. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE AND THE REPRESENTATION OF ETHNIC DIFFERENCE IN AMERICAN AND BRITISH SCIENCE FICTION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Javier A. -

History Report Freiburg HOT 24.02.2016 00 Through 01.03.2016 23

History Report Freiburg_HOT 24.02.2016 00 through 01.03.2016 23 Air Date Air Time Cat RunTime Artist Keyword Title Keyword Mi 24.02.2016 00:05 ARO 02:37 Basia Bulat Fool Mi 24.02.2016 00:08 ARO 03:55 Liima Amerika Mi 24.02.2016 00:12 DPR 03:52 Tocotronic Let there be rock Mi 24.02.2016 00:15 HIP 04:50 Black Twang So Rotton feat. Jahmali Mi 24.02.2016 00:20 SRO 02:19 Reverend And The Makers Mr Glasshalfempty Mi 24.02.2016 00:23 RCK 03:04 Oasis Hello Mi 24.02.2016 00:26 DPR 02:41 Tom Liwa & Flowerpornoes Planetenkind Mi 24.02.2016 00:28 NAC 03:25 Belle And Sebastian Get me away from here I'm dyin Mi 24.02.2016 00:32 ARO 03:55 Alligatoah Teamgeist Mi 24.02.2016 00:36 POP 03:23 Mumm-Ra She's got you high Mi 24.02.2016 00:39 SRO 04:05 Stereo Total Zu schön für dich Mi 24.02.2016 00:43 NAC 05:02 Richard Ashcroft C'mon People (We're Making It Now) Mi 24.02.2016 00:48 NAC 03:26 Shooting John Thirteen Highway Blues Mi 24.02.2016 00:52 EKR 03:54 Powernerd BMX Mi 24.02.2016 00:55 ARO 04:52 Yeasayer I Am Chemistry Mi 24.02.2016 00:60 EKR 03:07 Caribou Found Out Mi 24.02.2016 00:63 POP 03:37 Athlete Half Light Mi 24.02.2016 00:67 NAC 03:35 Teitur Shade Of A Shadow Mi 24.02.2016 00:71 NAC 06:02 Phosphorescent Cocaine Lights Mi 24.02.2016 01:05 NAC 03:31 Pelle Carlberg Telemarketing Mi 24.02.2016 01:09 J 00:02 Flüsterer_Ids2 Mi 24.02.2016 01:09 RCK 02:02 The Octagon Vermeer Mi 24.02.2016 01:11 SRO 04:18 DOTA Grenzen Mi 24.02.2016 01:15 POP 03:25 Hurricane #1 Think Of The Sunshine Mi 24.02.2016 01:18 NAC 02:21 Lea Rohm Maybe You Are (Asaf Avidan Cover) -

The Question of 'Nature': What Has Social Constructionism to Offer Feminist Theory?

The Question of ‘Nature’: What has Social Constructionism to offer Feminist Theory? Elisa Fiaccadori SOCIOLOGY RESEARCH PAPERS 2 The Question of ‘Nature’: What has Social Constructionism to offer Feminist Theory? The Question of ‘Nature’: What has Social Constructionism to offer Feminist Theory? 3 The Question of ‘Nature’: What has Social Constructionism to offer Feminist Theory? Elisa Fiaccadori The question of ‘nature’ is of particular up reinforcing exactly these constructed importance for feminist theorizing as differences between ‘men’ and ‘women’, feminists have long come to realise that it is ‘culture’ and ‘nature’, which they refuse on often upon this ‘concept’ that the giveness of the basis of their sexualising, racialising and sexual differences and, consequently, the universalising effects (see Butler, 1993; Alcoff inferiority of ‘women’, is assumed1. It is in Tong and Tuana, 1995; Flax in Nicholson, against biological determinism that feminists 1990). Instead, they are more concerned with have developed their most powerful theories problematising ‘nature’ by asserting the social and critiques of dominant categorisations of and cultural constructedness of the category ‘women’ (see, for example, de Beauvoir, ‘women’. According to post-structural 19892 ; Rich, 1981). Particularly, both ‘second feminists, it is only by acknowledging the wave feminists’ generally, and eco-feminists constructedness of ‘nature’, consequently of specifically, tended to criticise dominant ‘women’ (and ‘men’), that ‘spaces for more conceptualisations of women as ‘naturally’ plural forms of self-identification’ can be inferior and assert the political importance of created (in Kemp and Squires, 1997: 469). reclaiming ‘nature’, ‘the natural’ and ‘the feminine’ from the grip of exploitative To the extent that social constructionism scientific patriarchalism (in Kemp and Squires, problematises ‘nature’ as given, it offers 1997: 469). -

Northwestern Poet Plays with Fire Awakening the Nation's Taste Buds

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY WEINBERG COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES NORTHWESTERN POET PLAYS WITH FIRE AWAKENING THE NATION’S TASTE BUDS THE FULBRIGHT: GATEWAY TO THE WORLD FALL/WINTER 2006/2007 THE MAGAZINE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES VOLUME 7, NUMBER 2 7 Will Butler: Poet and Rock Star By Nancy Deneen NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Photo by Mary Hanlon FROM THE DEAN WEINBERG COLLEGE OF ARTS 10 Fulbrighters in AND SCIENCES DEPARTMENTS the Field: What They Learned, common sentiment expressed to stu- Many students are deeply concerned with the 1 What they Gave COVER PHOTOS, CROSSCURRENTS IS dents, from freshman welcoming ethical dilemmas posed by the “big issues.” From the Dean FROM TOP: PUBLISHED TWICE addresses all the way to commencement These talented young adults have the intellectual by Nancy Deneen A YEAR FOR ALUMNI, A speeches, is that we—faculty, administrators, flexibility, the openness to new ideas, the won- 2 FROM THE ARCADE FIRE’S ALBUM, PARENTS, AND FUNERAL FRIENDS OF THE alumni, parents (in short, “adults”)—look to derful tendency to question our assumptions, that Letters COVER ART BY TRACY MAURICE JUDD A. AND MARJORIE today’s students (the “next generation”) to make we expect will enable them to find ways to bridge 16 WEINBERG COLLEGE FRANK JONES IN A STORY IN OF ARTS major contributions in resolving the complex the divide on the most challenging issues: stem 3 The Far-Reaching Impact THE ARIZONA REPUBLIC AND SCIENCES, issues we face as a society. cells and cloning, free trade and the protection of of the Center for Faculty Awards PHOTO BY DAVID WALLACE NORTHWESTERN It is not just the adults who hope that the next jobs, immigration, national security, preservation International Economics UNIVERSITY. -

A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Minnesota By

NOWHERE TO GO BUT FORWARD: THE FICTION OF OCTAVIA E. BUTLER A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of Minnesota by Emily Kathryn Anderson in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dr. Lois Cucullu May 2016 © Emily Kathryn Anderson 2016 Acknowledgements Thank you to Dr. Lois Cucullu for all of her generosity and insight. i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to Eric Prindle for his love, support, and gentle encouragement. ii Table of Contents Introduction: The Seeds of Dissent: Science Fiction’s Radical Promise ......................................... 1 Disastrous Pasts and Hopeful Tomorrows: Octavia Butler Rewrites Apocalypse......................... 31 Radical Hope and Everyday Work: Octavia Butler Rewrites Utopia ............................................ 61 All That History Will Allow: The Use of Time in Octavia Butler’s Kindred ............................... 99 Almost Human, Always Reaching: Octavia Butler’s Cyborgs, Vampires, and Shape-shifters ... 124 The Future Is Now: Aliens and Other Alienated Bodies in Octavia Butler’s Fiction .................. 157 Afterword: Black to the Future Part II: The Legacy of Octavia Butler’s Oeuvre ........................ 195 Works Cited ................................................................................................................................. 205 iii Introduction: The Seeds of Dissent: Science Fiction’s Radical Promise “What good is science fiction to Black people? What good is science fiction’s thinking about the present, the future, and the past? What good is its tendency to warn or to consider alternative ways of thinking and doing? What good is its examination of the possible effects of science and technology, or social organization and political direction? At its best, science fiction stimulates imagination and creativity. It gets reader and writer off the beaten track, off the narrow, narrow footpath of what ‘everyone’ is saying, doing, thinking—whoever ‘everyone’ happens to be this year. -

Indie Mixtape Is Pleased to Announce a New Podcast Called Indiecast, Hosted by Myself and Long-Time Music Critic Ian Cohen of Pitchfork and Stereogum Fame

:: View email as a web page :: What if you could listen to this newsletter along with reading it every week? Starting on Friday, July 31, Indie Mixtape is pleased to announce a new podcast called Indiecast, hosted by myself and long-time music critic Ian Cohen of Pitchfork and Stereogum fame. Each week, Ian and I will talk about all the latest news in indie music. We will review albums, break down trends, expose exciting new artists, and give you all the necessary context to understand what’s happening in the indie world. And we'll also pointlessly rank things — whether it’s the best indie albums of the aughts, the greatest Phoebe Bridgers tracks, or our favorite chillwave songs. The show debuts on July 31, and there will be new episodes every Friday. Listen to the trailer and subscribe here. -- Steven Hyden, Uproxx Cultural Critic and author of This Isn't Happening: Radiohead's "Kid A" And The Beginning Of The 21st Century PS: Was this email forwarded to you? Join our band here. In case you missed it... Our YouTube channel is now the go-to destination for official music videos from both The Jesus & Mary Chain and Faith No More. Since last we spoke, Taylor Swift announced and released a new album, and it features The National's Aaron Dessner and Bon Iver. Check out our full review down below. A new study found that digital devices are now the most common method of listening to music, accounting for 53% of total daily listening time, and overtaking analog listening devices like radio and turntables for the first time ever.