A Case Study of the Steinmetz Academic Centre for Wellness and Sports Science : Differential Program Preference Ratings by Group Constituency, Race, and Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

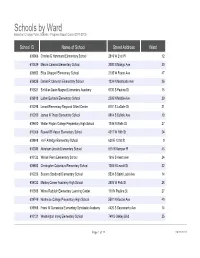

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

18-0124-Ex1 5

18-0124-EX1 5. Transfer from George Westinghouse High School to Education General - City Wide 20180046075 Rationale: FY17 School payment for the purchase of ventra cards between 2/1/2017 -6/30/2017 Transfer From: Transfer To: 53071 George Westinghouse High School 12670 Education General - City Wide 124 School Special Income Fund 124 School Special Income Fund 53405 Commodities - Supplies 57915 Miscellaneous - Contingent Projects 290003 Miscellaneous General Charges 600005 Special Income Fund 124 - Contingency 002239 Internal Accounts Book Transfers 002239 Internal Accounts Book Transfers Amount: $1,000 6. Transfer from Early College and Career - City Wide to Al Raby High School 20180046597 Rationale: Transfer funds for printing services. Transfer From: Transfer To: 13727 Early College and Career - City Wide 46471 Al Raby High School 369 Title I - School Improvement Carl Perkins 369 Title I - School Improvement Carl Perkins 54520 Services - Printing 54520 Services - Printing 212041 Guidance 212041 Guidance 322022 Career & Technical Educ. Improvement Grant (Ctei) 322022 Career & Technical Educ. Improvement Grant (Ctei) Fy18 Fy18 Amount: $1,000 7. Transfer from Facility Opers & Maint - City Wide to George Henry Corliss High School 20180046675 Rationale: CPS 7132510. FURNISH LABOR, MATERIALS & EQUIPMENT TO PERFORM A COMBUSTION ANALYSIS-CALIBRATE BURNER, REPLACE & TEST FOULED PARTS: FLAME ROD, WIRE, IGNITOR, CABLE, ETC... ON RTUs 18, 16, 14 & 20 Transfer From: Transfer To: 11880 Facility Opers & Maint - City Wide 46391 George Henry Corliss High School 230 Public Building Commission O & M 230 Public Building Commission O & M 56105 Services - Repair Contracts 56105 Services - Repair Contracts 254033 O&M South 254033 O&M South 000000 Default Value 000000 Default Value Amount: $1,000 8. -

Chicago River Schools Network Through the CRSN, Friends of the Chicago River Helps Teachers Use the Chicago River As a Context for Learning and a Setting for Service

Chicago River Schools Network Through the CRSN, Friends of the Chicago River helps teachers use the Chicago River as a context for learning and a setting for service. By connecting the curriculum and students to a naturalc resource rightr in theirs backyard, nlearning takes on new relevance and students discover that their actions can make a difference. We support teachers by offering teacher workshops, one-on-one consultations, and equipment for loan, lessons and assistance on field trips. Through our Adopt A River School program, schools can choose to adopt a site along the Chicago River. They become part of a network of schools working together to monitor and Makingimprove Connections the river. Active Members of the Chicago River Schools Network (2006-2012) City of Chicago Eden Place Nature Center Lincoln Park High School * Roots & Shoots - Jane Goodall Emmet School Linne School Institute ACE Tech. Charter High School Erie Elementary Charter School Little Village/Lawndale Social Rush University Agassiz Elementary Faith in Place Justice High School Salazar Bilingual Education Center Amundsen High School * Farnsworth Locke Elementary School San Miguel School - Gary Comer Ancona School Fermi Elementary Mahalia Jackson School Campus Anti-Cruelty Society Forman High School Marquez Charter School Schurz High School * Arthur Ashe Elementary Funston Elementary Mather High School Second Chance High School Aspira Haugan Middle School Gage Park High School * May Community Academy Shabazz International Charter School Audubon Elementary Galapagos Charter School Mitchell School St. Gall Elementary School Austin High School Galileo Academy Morgan Park Academy St. Ignatius College Prep * Avondale School Gillespie Elementary National Lewis University St. -

Action Civics Showcase

16th annual Action Civics showcase Bridgeport MAY Art Center 10:30AM to 6:30PM 22 2018 DEMOCRACY IS A VERB WELCOME to the 16th annual Mikva Challenge ASPEN TRACK SCHOOLS Mason Elementary Action Civics Aspen Track Sullivan High School Northside College Prep showcase The Aspen Institute and Mikva Challenge have launched a partnership that brings the best of our Juarez Community Academy High School collective youth activism work together in a single This has been an exciting year for Action initiative: The Aspen Track of Mikva Challenge. Curie Metropolitan High School Civics in the city of Chicago. Together, Mikva and Aspen have empowered teams of Chicago high school students to design solutions to CCA Academy High School Association House Over 2,500 youth at some of the most critical issues in their communities. The result? Innovative, relevant, powerful youth-driven High School 70 Chicago high schools completed solutions to catalyze real-world action and impact. Phillips Academy over 100 youth action projects. High School We are delighted to welcome eleven youth teams to Jones College Prep In the pages to follow, you will find brief our Action Civics Showcase this morning to formally Hancock College Prep SCHEDULE descriptions of some of the amazing present their projects before a panel of distinguished Gage Park High School actions students have taken this year. The judges. Judges will evaluate presentations on a variety aspen track work you will see today proves once again of criteria and choose one team to win an all-expenses paid trip to Washington, DC in November to attend the inaugural National Youth Convening, where they will be competition that students not only have a diverse array able to share and learn with other youth leaders from around the country. -

Union Teacher

www.ctunet.com Vol. 75, No. 8 The OfficialUNION Publication ofTEACHER the Chicago Teachers Union June 2012 INSIDE: • May 23 Rally • Student Art Awards • Charter Bill Defeated • Matt Farmer: Teachers Don’t Like Bullies Chicago Union Teacher Staff CTU congratulates its • Kenzo Shibata President’s Message Editor 2012-2013 Scholarship • Nathan Goldbaum Award Winners Associate Editor President Karen Lewis’ Remarks at the June 1st Strike Each student received a $1,000 Authorization Press Conference • April Stigger Scholarship: Advertising Manager Rebecca A. Cuculich – Jacqueline B. Vaughn Scholarship Chicago teachers and paraprofessionals are fed up. Chicago Teachers Union Jada Jamison – John M. Feweks Scholarship They are tired of being blamed, bullied and belittled by the very District Kyla Thomas – Jonathan G. Kotsakis Scholarship that should support them. Officers Paris Olawale – Robert M. Healey Scholarship We live in a City that no longer trusts educators as important resources in KaJuan Jackson – Charles E. Usher Scholarship helping our youth to develop values, skills and the knowledge required for • Karen Lewis Mario J. Diaz – Mary J. Harrick Scholarship them to enter adult life as thinking and engaged citizens. President Benjamin Radinsky – Ernestine Cain Brown Scholarship We live in a City that has done everything it can to take the joy out of Jimmy Guo – David M. Peterson Scholarship • Jesse Sharkey teaching and learning. Vice President Zobia Chunara – William “Bill” Buchanan Scholarship George V. Vidas – Glendis Hambrick Scholarship Teachers in Chicago are being deskilled, unceremoniously removed from the process of school governance and reduced to technicians and babysitters. We’re being asked to work • Michael Brunson Eleanor Spencer – John Marshall Scholarship What we really Recording Secretary harder and longer in order to further inflict upon our students mindless experiment after mindless experiment. -

Chicago Public Schools City Championships 2011- 2012 January 29, 2012 Place Score Name 1St 2Nd 3Rd 4Th 5Th 6Th

Chicago Public Schools City Championships 2011- 2012 January 29, 2012 Place Score Name 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 1 256.00 Lane Tech High School 3 7 1 2 2 153.50 Bowen High School 3 1 1 2 1 3 87.00 Taft High School 2 1 1 1 4 67.00 Chicago Agi Science 1 1 1 1 5 64.00 King High School 1 1 1 1 6 62.00 Uplift High School 3 1 7 46.00 Northside Prep 2 1 8 45.00 Fenger High School 1 1 9 43.00 Foreman High School 1 1 1 10 42.00 Austin High School 2 1 11 38.00 Kelly High School 1 1 1 12 36.00 Curie High School 2 36.00 Brooks High School 3 14 32.00 Julian High School 1 1 15 30.00 Simeon High School 1 1 16 26.00 Clemente High School 1 26.00 Amundsen High School 1 1 18 24.00 Mather High School 1 24.00 Morgan Park High School 2 20 23.00 Juarez High School 1 1 21 21.00 Kenwood Academy High School 2 22 20.00 Carver High School 1 23 16.00 Douglass High School 2 16.00 Dunbar High School 2 16.00 Hubbard High School 1 26 15.00 Roberson High School 1 1 27 13.00 Manley High School 1 28 11.00 Phoenix Military Academy 1 11.00 Urban Prep High School 1 30 8.00 Gage Park High School 1 31 7.00 Collins High School 1 32 3.00 Team Englewood 3.00 Roosevelt High School 34 2.00 Kennedy High School 35 1.00 Harper High School 1.00 Corliss High School 37 0.00 Al Raby High School 0.00 Farragut High School 0.00 Little Village High School 0.00 Orr High School 0.00 Marshall High School 0.00 Crane High School 0.00 Phillips High School 0.00 Bronzeville 0.00 Bogan High School * Team has non-scoring wrestler Chicago Public Schools City Championships 2011- 2012 January 29, 2012 Place -

Chicago Public Schools City Championships 2012-2013 January 27, 2013 Place Score Name 1St 2Nd 3Rd 4Th 5Th 6Th

Chicago Public Schools City Championships 2012-2013 January 27, 2013 Place Score Name 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 1 142.50 Bowen High School 1 3 1 3 2 139.50 Lane Tech High School 2 3 1 1 1 3 123.00 Taft High School 3 1 1 1 1 4 65.00 Westinghouse High School 1 2 1 5 47.00 Northside Prep 1 1 6 46.00 Simeon High School 1 1 1 7 45.50 Brooks High School 1 2 8 45.00 Uplift High School 1 2 1 9 43.50 Kelly High School 1 2 10 42.00 Juarez High School 2 11 41.00 Amundsen High School 1 1 12 39.00 Dunbar High School 1 1 2 13 38.00 King High School 1 1 14 37.00 Mather High School 2 15 36.00 Morgan Park High School 1 1 16 33.00 Austin High School 1 1 17 29.00 Kennedy High School 1 1 29.00 Hyde Park High School 1 2 19 28.00 Chicago Agi Science 1 1 20 27.00 Corliss High School 1 1 21 24.00 Lindblom High School 1 22 23.50 Douglass High School 1 23 21.00 Kenwood Academy High School 1 1 24 19.00 Dusable High School 1 25 18.00 Foreman High School 2 18.00 Senn High School 1 27 17.00 Curie High School 1 17.00 Hubbard High School 1 17.00 Carver High School 1 30 9.00 Marshall High School 1 31 8.00 Roberson High School 1 32 7.00 Julian High School 1 7.00 Chicago Vocational Career Academy 1 7.00 Solorio High School 1 35 6.00 Clemente High School 1 36 3.00 Urban Prep High School 37 2.00 Roosevelt High School 2.00 Wahington High School 39 1.00 Bronzeville 1.00 Gary Comer High School 41 0.00 Phoenix Military Academy 0.00 Al Raby High School 0.00 Farragut High School 0.00 Little Village High School 0.00 Orr High School * Team has non-scoring wrestler Chicago Public Schools -

Report of the President of Rtac Inside This Issue.

RETIRED TEACHERS ASSOCIATION OF CHICAGO Since 1926 VOL. LXIV JULY 2008 NO. 3 REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT OF RTAC Thanks to each of you who braved the remod- bills to consider. Further action in this session is eling/construction obstacles at the Palmer House not certain. to attend our Spring Luncheon. The Grand Ball- room, filled with an overflow crowd of The year 2008 continues to be an over 800 attractive guests, colorful pre- election year at both the local and national sentation of meals, and attentive serv- levels. It remains important that we con- ers providing quality service, contrib- tinue to stay politically informed and ac- uted to the most festive RTAC luncheon tive. This legislative session was con- I have been privileged to attend. With a cluded at the end of May. However, as few more training sessions, we speak- the climate of State government seems to ers shall possibly even master the mike. have become more divisive and hostile, Ethel Philpott who knows what new surprises and pro- Thanks also to each of you who posals we shall face? Remember, RTAC turned out for the Service Committee meeting, at lost several very good friends in this past primary 10a.m. on Thursday May 22. The hand-written per- election. Hopefully we can avoid a repeat in the sonal contacts that members send to our most next primary. senior RTAC members form a substantial part of their contacts with the world, as their answering Our pension fund cash reserves continue to letters vividly remind us.The additional hands tak- attract increasing attention among the ethically chal- ing part this month were greatly appreciated. -

Gocps Elementary and High School Guide 2020

Fall/Winter 2019 Dear Parent and/or Guardian: Thank you for your interest in the Chicago Public Schools! Our mission is to provide a wide variety of schools and programs that meet the interests and needs of Chicago’s families. The Elementary and High School Guide provides information about the application process for both elementary and high schools. This guide is arranged by application type (Choice, Selective Enrollment, and High School) and contains the following: • An overview of the process, from application to notification. • Frequently asked questions and answers for each type of application, organized according to the type of question • Details regarding the selection process • Helpful hints for students with disabilities • Tips for applying • Eligibility requirements • A glossary of academic programs or elementary schools • A list of elementary and high schools by prorgram You can apply online or, if you prefer, the paper application is also available. We hope that you will find this guide to be an informative and easy-to-use tool for assisting you with the application process. If you have questions or need assistance of any kind, please don’t hesitate to contact the Office of Access and Enrollment at (773) 553-2060 or [email protected]. We are here to serve! Sincerely, fir Tony T. Howard Executive Director Rev. 11-5-2019 2 elementary and high school guide table of contents part 1 INTRODUCTION - ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS page 2 part 2 ESSENTIAL INFO page 6 part 3 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS-IN-COMMON page 10 part 4 CHOICE ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS -

High School Progress Report Card (2012-2013)

Chicago Public Schools – High School Progress Report Card (2012-2013) School ID School Short Name School Name 610340 Chgo Acad HS Chicago Academy High School 400018 Austin Bus & Entrp HS Austin Business and Entrepreneurship Academy HS 610524 Alcott HS Alcott High School for the Humanities 609678 Jones HS William Jones College Preparatory High School 609692 Simeon HS Neal F Simeon Career Academy High School 609759 Clemente HS Roberto Clemente Community Academy High School 609735 Tilden HS Edward Tilden Career Community Academy HS 609713 Hyde Park HS Hyde Park Academy High School 609729 Schurz HS Carl Schurz High School 609715 Kelly HS Thomas Kelly High School 609753 Chgo Agr HS Chicago High School for Agricultural Sciences 609698 Bogan HS William J Bogan High School 609709 Gage Park HS Gage Park High School 609739 Washington HS George Washington High School 609760 Carver Military George Washington Carver Military Academy HS 610391 Lindblom HS Robert Lindblom Math & Science Academy HS 609720 Lane HS Albert G Lane Technical High School 610502 Marine Military HS Marine Military Math and Science Academy 609768 Hope HS Hope College Preparatory High School Page 1 of 130 10/03/2021 Chicago Public Schools – High School Progress Report Card (2012-2013) Street Address City State ZIP 3400 N Austin Ave Chicago IL 60634 231 N Pine Ave Chicago IL 60644 2957 N Hoyne Ave Chicago IL 60618 606 S State St Chicago IL 60605 8147 S Vincennes Ave Chicago IL 60620 1147 N Western Ave Chicago IL 60622 4747 S Union Ave Chicago IL 60609 6220 S Stony Island Ave Chicago -

Fall Haul Tallies by School Through Nov 16, 2015 Addison Trail High

Fall Haul Tallies by School through Nov 16, 2015 Addison Trail High School (Addison) 7,778 Dupage College (Addison) 51 Lutherbrook Academy (Addison) - Jacobs High (Algonquin) 5,665 Antioch High School (Antioch) 1,088 Christian Liberty Academy (Arlington Heights) 30 Forest View School (Arlington Heights) 206 Hersey High School (Arlington Heights) 7,786 Metropolitan Preparatory School (Arlington Heights) - St Viator High School (Arlington Heights) 2,941 Van Guard School (Arlington Heights) - Aurora Central (Aurora) 666 Aurora Christian (Aurora) 711 Aurora East (Aurora) 8,724 Aurora North (Aurora) 75 Aurora West (Aurora) 4,272 Illinois Mathematics And Science Academy (Aurora) 71 Indian Plains High School (Aurora) 50 Marmion Academy (Aurora) 607 Metea Valley High School (Aurora) 4,690 Rosary High School (Aurora) 303 Waubonsie Valley High School (Aurora) 5,521 Barrington High School (Barrington) 999 Bartlett High School (Bartlett) 12,900 Batavia High School (Batavia) 10,062 Fenton High School (Bensenville) 1,173 Morton West High School (Berwyn) 13,480 Bismarck-Henning High School (Bismarck) - Bolingbrook High School (Bolingbrook) 22,340 Faith Baptist Academy (Bourbonnais) - Bradley - Bourbonnais High School (Bradley) - Reed-Custer High School (Braidwood) - Islamic School (Bridgeview) - Christ Lutheran High School (Buckley) - Buffalo Grove High School (Buffalo Grove) 2,731 Jordan Baptist School (Burbank) - Queen Of Peace High School (Burbank) - Reavis High School (Burbank) - St Laurence High School (Burbank) 1,060 Burlington Central (Burlington) -

Action Civics Showcase

Democracy is a verb. 15th Annual Action Civics Showcase Tuesday, May 23, 2017 4:00-6:00PM Chicago Cultual Center 78 E Washington St Chicago, IL 60602 Presented in partnership with LIED PRINTIN AL G UNION ® TRADES28 LABEL COUNCIL 458 CHICAGO, IL WELCOME FUNDERS & SPONSORS to the Action Civics Showcase Democracy is a verb. 2 27 THANK YOU ACTION CIVICS SCHOOLS 26 3 ACTION CIVICS SCHOOLS - cont. THANK YOU, TEACHERS AND ADULT ALLIES! PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS Alcott College Prep 4 25 PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS Aspira Haugan Middle School World Language High School Association House High School CONGRATULATIONS! Bogan High School 24 5 PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS Bowen High School Brighton Park Neighborhood Council Bronzeville Scholastic Institute Westinghouse College Prep Brooks College Prep Williams Prep High School Burroughs Elementary 6 23 PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS Tilden High School CCA Academy UIC College Prep High School Uplift Community High School Chicago District Association of Students Councils Chicago Vocational Career Academy Vaughn Occupational High School Clark Academic Prep Von Steuben M.S.C. Washington High School 22 7 PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS Solorio Academy High School Corliss High School Crown Community Academy Sullivan High School 8 21 PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS Curie Metro High School RTC Medical Prep High School DeVry University Advantage Academy Senn High School Disney II Magnet High School Excel Academy of the Southwest Shields Middle School 20 9