1572006835860.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Unparalleled Crossbow Gear

2018 Unparalleled Crossbow Gear. Shoot the Best. Be the Best. We believe in performance and maximizing every shot through meticulous Like you, we do not fear hard work and we are unafraid to dream of something attention to detail and blending handmade craftsmanship with modern better. It’s that drive that compels us to produce the materials. We believe in people who continuously look for an edge — people absolute finest crossbow strings, using the right blend of modern materials, who know that every shot counts. machinery and time-honored techniques. We believe that making innovative crossbow accessories that provide Work ethic, dedication to craftsmanship, and the relentless pursuit of the unparalleled gains in performance are the best way to enhance the perfect shot — we are BlackHeart and we craft crossbow strings. experience, shot after shot. modern craftsmanship crossbow case* Protect your crossbow with the meanest looking case on the market. It features tear / abrasion resistant material and tactical styling. Built to be highly functional and rugged, the Chamber truly beats the competition. 35" Overall, 23" Cam-to-Cam Containment 9.5" Scope Accommodation Height Durable Duraflex ® Components 840D Polyester #81332 New for 2018! ™ *Preproduction rendering. Final product may vary. CHAMBER Visit BlackHeartArchery.com for updates. crossbow protection cocking device Our ByPass™ Cocking Device is the future of crossbow cocking. Experience unmatched ease-of-use thanks to the 3:1 pulley system which makes loading your crossbow a breeze and allows your focus to shift to what 200lbs of required force matters — the perfect shot. 3:1 Pulley System Reduces Effort By Up to 67% Easiest Cocking Solution Available Patent Pending Technology #81368 New for 2018! 100 lbs of load 100lbs of load 66.6 lbs 66.6 lbs 33.33 lbs effort 33.33 lbs effort 66.6 lbs 66.6 lbs ™ 66.6 lbs 66.6 lbs BYPASS shooting accessories Anchor Anchor DuraWeave™ String Construction BlackHeart strings and cables are produced using our exclusive DuraWeave process. -

Vampires in Brooklyn Part 1 6

MARVEL.COM $3.99 RATED 0 0 6 1 1 US 6 T+ 7 59606 08783 9 VAMPIRES INBROOKLYN BARNES •CABROLROSENBERG PART 1 Sam Wilson stepped away from the mantle of Captain America to build a legacy of his own--as the high-flying FALCON! Along with his new protégé, Rayshaun Lucas, A.K.A. the PATRIOT, he’s embarking on a mission to decide what kind of hero he wants to be. After the Hydra takeover, Falcon went to Chicago to find himself--and to broker a truce between two warring gangs. He ran afoul of Blackheart, son of Mephisto, who cast Falcon’s soul into hell. With help from his friends, he was able to return to his body and defeat Blackheart, but his victory made him some powerful enemies… VAMPIRES IN BROOKLYN Writer • RODNEY BARNES Editor • ALANNA SMITH Artist • SEBASTIÁN CABROL Executive Editor • TOM BREVOORT Editor in Chief • C.B. CEBULSKI Color Artist • RACHELLE ROSENBERG Chief Creative Officer • JOE QUESADA Letterer • VC’s JOE CARAMAGNA President • DAN BUCKLEY Cover Art • JAY ANACLETO & ROMULO FAJARDO JR. Executive Producer • ALAN FINE FALCON No. 6, May 2018. Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. © 2018 MARVEL No similarity between any of the names, characters, persons, and/or institutions in this magazine with those of any living or dead person or institution is intended, and any such similarity which may exist is purely coincidental. -

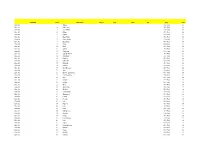

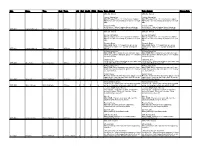

Set Name Card Description Sketch Auto

Set Name Card Description Sketch Auto Mem #'d Odds Point Base Set 1 Angela 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 2 Anti-Venom 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 3 Doc Samson 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 4 Attuma 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 5 Bedlam 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 6 Black Knight 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 7 Black Panther 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 8 Black Swan 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 9 Blade 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 10 Blink 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 11 Callisto 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 12 Cannonball 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 13 Captain Universe 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 14 Challenger 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 15 Punisher 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 16 Dark Beast 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 17 Darkhawk 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 18 Collector 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 19 Devil Dinosaur 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 20 Ares 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 21 Ego The Living Planet 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 22 Elsa Bloodstone 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 23 Eros 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 24 Fantomex 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 25 Firestar 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 26 Ghost 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 27 Ghost Rider 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 28 Gladiator 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 29 Goblin Knight 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 30 Grandmaster 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 31 Hazmat 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 32 Hercules 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 33 Hulk 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 34 Hyperion 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 35 Ikari 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 36 Ikaris 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 37 In-Betweener 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 38 Khonshu 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 39 Korvus 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 40 Lady Bullseye 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 41 Lash 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 42 Legion 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 43 Living Lightning 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 44 Maestro 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 45 Magus 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 46 Malekith 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 47 Manifold 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 48 Master Mold 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 49 Metalhead 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 50 M.O.D.O.K. -

Vs. System 2PCG

Upper Deck Vs System 2PCG Card Rules FAQ - Card Ruling FAQ Card 1 Keyword/Super Related Cards Related Question Answer Source UDE Approved Power/XP Keywords Adam Warlock If I don’t use his Emerge power, will he recover normally during Yes. But he’s huge! Spend that MIGHT and start bashing with him right UDE FAQ 6.10.16 my next Recovery Phase? away, man! Baron Mordo (MC) Hypnotize Sister Ripley/Ripley #8 If I Hypnotize a Ripley #8 L2 that started the game as Sister Ripley #8 Level 1. A character will always become the level one version FB Post - Chad Ripley, which Level 1 Character does she become? Sister of what it is. Daniel Ripley or Ripley#8 level 1? Baron Mordo (MC) Hypnotize Does Hex prevent a Hypnotized character from truning back into No, Hypnotize creates a modifier with an expiration that temporarily FB Post - Kirk Level 2 at the start of my next turn? makes a character its Level 1 version. When that modifer expires it (confirmed by becomes its Level 2 version again, and this is not conisdered Leveling Chad) up. Black Cat (MC) Cross their Path Satana Lethal If Satana is in play and Black Cat attacks a defender and uses Daze counts as stunning, but Lethal was changed to work when a FB Post - Chad Cross their Path to Daze that character, is it KO'd by Lethal? wounding a defending supporting character. Since Daze does not Daniel wound, lethal is not applied. Blackheart Created from Evil Even the Odds Even the Odds targeting Blackheart. -

US RIGHTS LIST Quercus Quercus US Rights List

Spring 2020 US RIGHTS LIST Quercus Quercus US Rights List PAGES.indd 2 26/02/2020 17:04 FICTION QUERCUS General Fiction 4 Quercus is a fast-growing publisher with a uniquely Crime & Thriller 9 international author base and a reputation for creative, high-energy bestsellers that surprise and delight the Literary Fiction 23 market. Historical Fiction 28 IMPRINTS Fantasy, Science Fiction & Horror 32 Quercus Non-Fiction, under Katy Follain, publishes com- mercial megasellers including Stories for Boys Who Dare to Be Different and the Famous Five for Grown-Ups series, but NON-FICTION the list is increasingly narrative and international, from The Maths of Life and Death to My Friend Anna. Popular Science 41 Quercus Fiction, under Cassie Browne, publishes commercial bestsellers include JP Delaney, Beth O’Leary’s Exploration 43 The Flatshare, Elly Griffiths, Philip Kerr and Lisa Wingate, with particular strength in crime and thriller. General 49 MacLehose Press, under Christopher MacLehose, is the UK’s leading publisher of quality translated fiction and Self-development 55 non-fiction, with bestsellers such as David Lagercrantz, Joel Dicker, Virginie Despentes and Pierre Lemaitre. Nature 62 Riverrun, under Jon Riley, is our literary fiction, crime and non-fiction imprint. Peter May and Louise O’Neill are the standout stars, with quality crime writers William Shaw and RIGHTS TEAM Olivia Kiernan, and literary talents Daniel Kehlmann, Polly Clark and Dror Mishani building nicely. Rebecca Folland Rights Director - Hodder & Stoughton, Headline Jo Fletcher Books is a small but perfectly formed specialist John Murray Press & Quercus list publishing the very best in best science fiction, fantasy [email protected] and horror. -

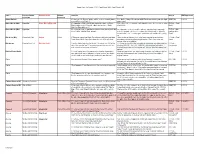

Current Change Date AFF-001 Captain Marvel Main Char

blac Name Type Cost Team Atk Def Health Flight Range Text - Original Text - Current Change Date AKA Ms. Marvel AKA Ms. Marvel Energy Absorption Energy Absorption Main [Energy]: Put a +1/+1 counter on Captain Main [Energy]: Put a +1/+1 counter on Captain Marvel for each other [ranged] character on your Marvel for each other [ranged] character on your side. side. Woman of War Woman of War Level Up (4) - When Captain Marvel stuns an Level Up (4) - When Captain Marvel stuns an AFF-001 Captain Marvel Main Character A-Force 2 4 6 x x enemy character in combat, she gains an XP. enemy character in combat, she gains an XP. AKA Ms. Marvel AKA Ms. Marvel Energy Absorption Energy Absorption Main [Energy]: Put a +1/+1 counter on Captain Main [Energy]: Put a +1/+1 counter on Captain Marvel for each other [ranged] character on your Marvel for each other [ranged] character on your side. side. Photonic Blast Photonic Blast Main [Skill]: Put a -1/-1 counter on an enemy Main [Skill]: Put a -1/-1 counter on an enemy character for each +1/+1 counter on Captain character for each +1/+1 counter on Captain AFF-002 Captain Marvel Main Character A-Force 4 6 6 x x Marvel. Marvel. A-Force Assemble! A-Force Assemble! Main [Skill]: When characters on your side team Main [Skill]: When characters on your side team attack the next time this turn, put a +1/+1 counter attack the next time this turn, put a +1/+1 counter on each of them. -

El Hombre Escondido En El Super Héroe.Pdf (1.711Mb)

UNIVERSIDAD DE CHILE Facultad des Ciencias Sociales Departamento de Sociología Carrera de Sociología EL HOMBRE ESCONDIDO EN EL SÚPER HOMBRE. Representaciones de la masculinidad en películas de superhéroes Memoria para optar al título de Sociólogo Estudiante: Felipe García soriano Profesor guía: Bernardo Amigo Latorre Santiago, 3 de Mayo de 2019 2 Anita, Miguel y Roro: Sin ustedes el viaje nunca habría comenzado. A mis abuelos: Ustedes son los héroes y heroínas de la edad dorada. Serán recordados por siempre. A la Liga, las Lauris, la Escuela, el Equipo y la Familia: Muchachs, ustedes son la prueba viviente de que un héroe llega lejos cuando está con otros. A ls profesors que me encontré en el camino: Han sido el símbolo que ha forjado quien soy Y por ultimo, a la Manu, mi pareja y compañera de viaje: Queda mucho por recorrer y un mundo que salvar 3 4 Resumen Esta investigación se sitúa en el marco de la Memoria para obtener el Título de Sociólogo. Se realizó un estudio que permite construir y caracterizar tipologías a partir de las masculinidades representadas en las películas del género cinematográfico de “Super héroes” entre el año 2000 y el año 2016. Se tuvo un enfoque de género en la investigación, comprendiendo las masculinidades como construcciones sociales sobre el sexo biológico. La investigación tendrá un carácter exploratorio-descriptivo. Se analizará un total de 164 personajes distribuidos en 30 películas. Se buscará lograr el objetivo a través de la metodología de análisis de contenido temático, analizando múltiples características referentes a los personajes de los filmes trabajados. -

Wednesday 13 July 2016 Manchester Metropolitan University

GRAPHIC GOTHIC MONDAY 11 – WEDNESDAY 13 JULY 2016 MANCHESTER METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY Conference schedule Sunday 10 July 2016 Welcome evening get together at Zouk (http://zoukteabar.co.uk/) from 7.30pm Monday 11 July 2016 9.00-9.20 Registration 9.20-9.30 Welcome address 9.30-10.30 Keynote 1 (Chair: Chris Murray) Matt Green – “An altered view regarding the relationship between dreams and reality”: The Uncanny Worlds of Alan Moore and Ravi Thornton 10.30-11.00 Coffee 11.00-12.30 Panel 1a – Gothic Cities (Chair: Esther De Dauw) Alex Fitch – Gotham City and the Gothic Architectural Tradition Sebastian Bartosch & Andreas Stuhlmann – Arkham Asylum: Putting the Gothic into Gotham City Guilherme Pozzer – Sin City: Social Criticism and Urban Dystopia Panel 1b – Monstrosity (Chair: Joan Ormrod) Aidan Diamond – Disability, Monstrosity, and Sacrifice in Wytches Edgar C. Samar – Appearances and Directions of Monstrosity in Mars Ravelo’s Comic Novels Panel 1c – Censorship (Chair: Julia Round) Paul Aleixo – Morality and Horror Comics: A re-evaluation of Horror Comics presented at the Senate Sub-Committee Hearings on Juvenile Delinquency in April 1954 Timothy Jones – Reading with the Horror Hosts in American Comics of the 1950s and 60s 12.30-1.30 Lunch 1.30-2.30 Academic Publishing Roundtable Discussion of the shape and strategies of academic publishing today led by Bethan Ball (Journals Manager, Intellect Books), Ruth Glasspool (Managing Editor, Routledge), and Roger Sabin (Series Editor, Palgrave). 2.30-3.30 Panel 2a – Gothic Worlds (Chair: Dave Huxley) -

The Henry Ford Hosts Marvel: Universe of Super Heroes Preview

The Henry Ford Hosts Marvel: Universe of Super Heroes Preview Party With Marvel Creators Chris Claremont and Ann Nocenti Tickets on sale now for March 26th Marvel: Universe of Super Heroes Preview Party. DEARBORN, Mich. (PRWEB) March 09, 2020 -- On March 26, 2020, guests are invited to join The Henry Ford for the official preview party celebrating the Midwest premiere of Marvel: Universe of Super Heroes, the world’s first and most extensive exhibition covering the more than 80-year legacy and impact of the Marvel Universe. Doors open at 5:30 pm, and the evening’s program will include a special “X-Men: The Marvel Mutantverse” panel discussion with exhibition curator Ben Saunders and legendary creators Chris Claremont and Ann Nocenti beginning at 7:30 pm. Tickets to Marvel: Universe of Super Heroes’ Preview Party are $45, with discounted tickets available. Chris Claremont is one of the most revered and important comic creators of all time. During the span of his career, he has won numerous industry awards, provided some of the medium’s most memorable stories and influenced generations of fans and creators. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, he built the X-Men into the most popular team in comics, and his characters and stories have provided the basis for wildly successful cartoons, films and television series. Ann Nocenti is a journalist and filmmaker, known in comics for writing Daredevil, editing X-Men and creating the Marvel characters Longshot, Typhoid, Spiral, Blackheart and more. She was the editor of the film magazine Scenario, and her films include “Disarming Falcons” and “Taking Chances”. -

22Nd Annual GSTBA Annotated Lists

22nd Annual Garden State Teen Book Awards Nominee Annotations Grade 6-8 Fiction Awkward by Svetlana Chmakova ISBN: 9780316381321 9780316381307 “After shunning Jaime, the school nerd, on her first day at a new middle school, Penelope Torres tries to blend in with her new friends in the art club, until the art club goes to war with the science club, of which Jaime is a member.” Circus Mirandus by Cassie Beasley ISBN: 9780525428435 “When he realizes that his grandfather's stories of an enchanted circus are true, Micah Tuttle sets out to find the mysterious Circus Mirandus--and to use its magic to save his grandfather's life.” Echo by Pam Munoz Ryan ISBN: 9780439874021 “Lost in the Black Forest, Otto meets three mysterious sisters and finds himself entwined in a prophecy, a promise, and a harmonica--and decades later three children, Friedrich in Germany, Mike in Pennsylvania, and Ivy in California find themselves caught up in the same thread of destiny in the darkest days of the twentieth century, struggling to keep their families intact, and tied together by the music of the same harmonica.” Friends for Life by Andrew Norriss ISBN: 9780545851862 “Francis Meredith is a boy who is interested in fashion and costuming, which has made him a target at school, but when he meets Jessica and Andi his life begins to change--Andi is an athletic girl with a reputation for fighting and family in the fashion business, and Jessica is a ghost who has no idea how she died.” Full Cicada Moon by Marilyn Hilton ISBN: 9780147516015 “In 1969 twelve-year-old Mimi and her family move to an all-white town in Vermont, where Mimi's mixed-race background and interest in "boyish" topics like astronomy make her feel like an outsider.” George by Alex Gino ISBN: 9780545812542 “BE WHO YOU ARE. -

Is There a List of Immortal Comic Book Characters

Is there a list of immortal comic book characters http://wiki.answers.com/Q/Is_there_a_list_of_immortal_comic... Ask us anything GO Sign In | Sign Up BLACK BUTLER (ANIME AND MANGA) BLEACH (ANIME AND MANGA) MORE English ▼ See what questions your friends are asking today. Legacy account member? Sign in. Categories Black Butler (Anime and Manga) Bleach (Anime and Manga) Books and Literature Celtic Mythology Comic Book Memorabilia Answers.com > Wiki Answers > Categories > Literature & Language > Books and Literature > Mythology > Is there a list of immortal comic book characters? Is there a list of immortal comic book characters? Ads Comic Books - All Titles www.mycomicshop.com/ Web's Largest Comic Book Store. Search by Title Issue or Condition! Superhero Characters www.target.com/ Superhero Characters Online. Shop Target.com. ContributorsAnswers & Edits Best Comic Books Online Supervisors www.comixology.com/online-comics Download Over 30,000 Digital Comics For Your PC, Mobile, or Tablet. 1 of 18 1/15/13 9:42 AM Is there a list of immortal comic book characters http://wiki.answers.com/Q/Is_there_a_list_of_immortal_comic... View Slide Show Zanbabe Trust: 3122 Mythology Supervisor Answer: Google Profile » The definition of the term immortality in comics may be debatable. For instance, some immortals Recommend Supervisor » seem to have died at least once but often reappear momentarily in a new revitalized incarnation; especially common amongst mythological characters (gods, goddesses, angels, demons, etc.). Deities, in fact, tend to be consistently immortal and are completely resistant to death and deterioration (e.g., Marvel Comics' Thor, Greek Gods, etc.). These beings are both functionally immortal and invulnerable and merely give the appearance of being slain for a temporary time before rematerializing. -

Summer Reading 2021 a Greeting from the Committee Contents

Hopkins GUIDE TO Summer Reading 2021 A Greeting from the Committee Contents Welcome to the 2021 Guidelines 2 A Word About Content 2 Summer Reading Guide! Required Books 4 List for Grades Seven and Eight In this publication, you will find reading recommendations General Fiction 5 that range across genre, identity, era and region, put Historical Fiction 9 together by your peers, your teachers, and your librarians. Nonfiction 10 If you are looking for Victorian romance, modernist poetry, Plays + Poetry 12 cultural critique, or hard sci-fi, you are in the right place. Mystery 13 If you are hankering for a play or a novella or a graphic Science Fiction + Fantasy 14 novel, welcome. If you do not know what you are looking for yet, that’s even better. List for Grades Nine through Twelve General Fiction 19 The Summer Reading Committee has been working all Historical Fiction 33 year to bring you an intuitive, streamlined publication that Nonfiction 39 will introduce you to new authors, new ideas and new Philosophy 51 texts. We have trimmed and edited, opened up space on Plays + Poetry 53 our metaphorical shelf, and added new titles that we feel Autobiographies + Memoirs 60 appeal to the adventurous, modern and diverse interests Mystery 65 of Hopkins School. Science Fiction + Fantasy 68 Short Stories + Essays 73 On the inside cover, you’ll find a bookmark. Think of this as a summer companion designed to keep your place in your current read, as well as help you discover other titles of interest. It has suggestions which will inspire you to explore the Guide more broadly, and it will travel with you into your new school year as a reminder of the books you’ve enjoyed over the break.