Łódzkie Studia Etnograficzne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poland and the UK – a Comparative Study Term: Autumn

Springwood School Medium Term Planning Topic: Poland and the UK – a comparative study Term: Autumn Pre Formal Semi Formal Formal Suggested Activities Suggested Activities Suggested Activities 1 Experience a range of foods from Poland and Explore and recognise a range of foods from Investigate different Traditional UK and the UK. Record responses and likes/dislikes. Poland and the UK. Polish foods. Discuss and understand the Food similarities and differences. Explore a range of foods from Poland and the Taste a range of traditional Polish and UK dishes. UK with our senses – smell, touch and taste. Use a variety of ways to communicate to show Use a range of traditional Polish and UK foods Observe and record responses and likes/dislikes. as a basis for different activities. likes/dislikes. Use traditional ingredients to make items from Investigate which foods are traditional Polish Make a range of traditional Polish or UK foods both countries that are similar, eg traditional and traditional UK, particularly linked to that are sensory in nature– compare and soup – compare and contrast. Christmas. contrast, eg breads. Explore different foods that are traditionally Design a traditional UK or traditional Polish Link to traditional foods that are eaten during eaten at Christmas in both countries. Use as a menu. Christmas time in both countries – taste, basis for writing and creative work. touch, smell a range of these foods. Visit a local Polish food shop to investigate Make own representations through cookery Set up a role play café area in class linked to both the type of foods that are traditionally eaten. -

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth As a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity*

Chapter 8 The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity* Satoshi Koyama Introduction The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita) was one of the largest states in early modern Europe. In the second half of the sixteenth century, after the union of Lublin (1569), the Polish-Lithuanian state covered an area of 815,000 square kilometres. It attained its greatest extent (990,000 square kilometres) in the first half of the seventeenth century. On the European continent there were only two larger countries than Poland-Lithuania: the Grand Duchy of Moscow (c.5,400,000 square kilometres) and the European territories of the Ottoman Empire (840,000 square kilometres). Therefore the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was the largest country in Latin-Christian Europe in the early modern period (Wyczański 1973: 17–8). In this paper I discuss the internal diversity of the Commonwealth in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and consider how such a huge territorial complex was politically organised and integrated. * This paper is a part of the results of the research which is grant-aided by the ‘Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research’ program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science in 2005–2007. - 137 - SATOSHI KOYAMA 1. The Internal Diversity of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Poland-Lithuania before the union of Lublin was a typical example of a composite monarchy in early modern Europe. ‘Composite state’ is the term used by H. G. Koenigsberger, who argued that most states in early modern Europe had been ‘composite states, including more than one country under the sovereignty of one ruler’ (Koenigsberger, 1978: 202). -

Implementation of the Helsinki Accords Hearings

BASKET III: IMPLEMENTATION OF THE HELSINKI ACCORDS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE NINETY-SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION THE CRISIS IN POLAND AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE HELSINKI PROCESS DECEMBER 28, 1981 Printed for the use of the - Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 9-952 0 'WASHINGTON: 1982 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE DANTE B. FASCELL, Florida, Chairman ROBERT DOLE, Kansas, Cochairman ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah SIDNEY R. YATES, Illinois JOHN HEINZ, Pennsylvania JONATHAN B. BINGHAM, New York ALFONSE M. D'AMATO, New York TIMOTHY E. WIRTH, Colorado CLAIBORNE PELL, Rhode Island MILLICENT FENWICK, New Jersey PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont DON RITTER, Pennsylvania EXECUTIVE BRANCH The Honorable STEPHEN E. PALMER, Jr., Department of State The Honorable RICHARD NORMAN PERLE, Department of Defense The Honorable WILLIAM H. MORRIS, Jr., Department of Commerce R. SPENCER OLIVER, Staff Director LYNNE DAVIDSON, Staff Assistant BARBARA BLACKBURN, Administrative Assistant DEBORAH BURNS, Coordinator (II) ] CONTENTS IMPLEMENTATION. OF THE HELSINKI ACCORDS The Crisis In Poland And Its Effects On The Helsinki Process, December 28, 1981 WITNESSES Page Rurarz, Ambassador Zdzislaw, former Polish Ambassador to Japan .................... 10 Kampelman, Ambassador Max M., Chairman, U.S. Delegation to the CSCE Review Meeting in Madrid ............................................................ 31 Baranczak, Stanislaw, founder of KOR, the Committee for the Defense of Workers.......................................................................................................................... 47 Scanlan, John D., Deputy Assistant Secretary for European Affairs, Depart- ment of State ............................................................ 53 Kahn, Tom, assistant to the president of the AFL-CIO .......................................... -

Changes in the Polish Agriculture in the Light of the Cap Implementation

MAREK WIGIER 10.5604/00441600.1151760 Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics – National Research Institute Warsaw CHANGES IN THE POLISH AGRICULTURE IN THE LIGHT OF THE CAP IMPLEMENTATION Abstract Agricultural policy in Poland supports the functioning of numerous types of agricultural models, including the following models: traditional, industrial, environmental, induced development and sustainable growth. The CAP objectives and mechanisms, as well as individual character- istics of the Polish agriculture indicate that in the long run the devel- opment pattern should be based on a dual model. Certain farms, while maintaining the basic requirements of environmental protection, should implement production methods ensuring high economic viability (indus- trial agriculture); other farms should base their development on more eco-friendly methods, which enable the use of environmental, social and cultural assets at hand (sustainable agriculture). This paper defines the most important development stages of global agriculture, indicates the connection between the necessity of state’s intervention policy and sustainable development, presents selected characteristics of the Polish agriculture with an analysis of the most important effects of implementing the CAP and illustrates the conclusions concerning the shape of the future long-term agricultural policy in Poland. Model of development of world agriculture Over the centuries, the most important task of agriculture was the production of food. This goal marked the development strategies of the whole food economy, which evolved from a peasant to farm-enterprise model (Fig. 1). Agriculture was the primary source of income and the most important work place in the rural areas. Industrialisation, mechanisation of production and the market mechanism trans- formed this situation. -

The Agricultural Sector in Poland and Romania and Its Performance Under the EU-Influence

Arbeitshefte aus dem Otto-Strammer-Zentrum Nr. 21 Berlin, Freie Universität Berlin, 2013 The Agricultural Sector in Poland and Romania and its Performance under the EU-Influence Von Simone Drost März 2013 CONTENT 1INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................... 6 2THE CHARACTER OF THE EU’S CAP: AN EVOLUTIONARY APPROACH....................................7 2.1The early CAP: From preventing food shortage to producing surpluses........................................................7 2.2Failed attempts of reform and years of immobility...............................................................................................8 2.3The MacSharry reform of 1991/92: Introducing fundamental structural changes...................................8 2.4Agenda 2000........................................................................................................................................................................8 2.5The 2003 reform: Fischler II..........................................................................................................................................9 2.62008 CAP Health Check....................................................................................................................................................9 2.72010 to 2013: Europe 2020 and the CAP................................................................................................................10 2.8Conclusion: Developing -

2014 Summer Newsletter

Newsletter of the Polish Cultural Council • Vol. 12 • Summer/Fall 2014 Remembering My 93 year old aunt passed away two English, in a Polish neighborhood in sto lat, net zero zero sum, , , zero sum, months ago. She was the last of my Creighton as well as Canonsburg, you zero sum, net zero zero sum, net zero father’s siblings. Therefore, the last direct would think she should be fluent in sum! connection to my Polish ancestors who Polish, right? My sister luckily recorded this for pos- came to America is gone. terity; however, the lesson for all of us Aunt Irene was in a nurs- is that in time, memories fade. ing home in Brackenridge Message from the President And when we are gone, they during the last few years. She always are gone forever. In Aunt Irene’s case had her wits even though her legs failed Irene had been away from speaking she had a foggy recollection of her first her. When Marysia and I visited her in the Polish for well over 30 years since her language, but it simply faded away over summer, she insisted on us bringing ice mother’s passing. She forgot her first lan- the years. And with her passing, so did cream sundaes. In the winter months, guage. She still had knowledge of the food her memories. pierogi, kielbasa and krysiki were on the names, like pierogi, kielbasa and chrusci- PCC board member Mary Lou Ellena menu. ki, but her Polish language just left her. is working on “Polish Hill Revisited”, the On Aunt Irene’s 92nd birthday, my sis- Marysia would speak to her in Polish, but second in a series of first-hand, personal ters were at the assisted living home she just didn’t get it. -

Subsistence Agriculture in Central and Eastern Europe: How to Break the Vicious Circle?

Studies on the Agricultural and Food Sector in Central and Eastern Europe Subsistence Agriculture in Central and Eastern Europe: How to Break the Vicious Circle? edited by Steffen Abele and Klaus Frohberg Subsistence Agriculture in Central and Eastern Europe: How to Break the Vicious Circle? Studies on the Agricultural and Food Sector in Central and Eastern Europe Edited by Institute of Agricultural Development in Central and Eastern Europe IAMO Volume 22 Subsistence Agriculture in Central and Eastern Europe: How to Break the Vicious Circle? Edited by Steffen Abele and Klaus Frohberg IAMO 2003 Bibliografische Information Der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists the publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the internet at: http://dnb.ddb.de. © 2003 Institut für Agrarentwicklung in Mittel- und Osteuropa (IAMO) Theodor-Lieser-Straße 2 062120 Halle (Saale) Tel. 49 (345) 2928-0 Fax 49 (345) 2928-199 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.iamo.de ISSN 1436-221X ISBN 3-9809270-2-4 INTRODUCTION STEFFEN ABELE, KLAUS FROHBERG Subsistence agriculture is probably the least understood and the most neglected type of agriculture. In a globalised, market-driven world, it remains at the same time a myth and a marginal phenomenon. Empirically, subsistence agriculture for a long time seemed to be restricted to developing countries, with only a few cases reported in Western Europe (CAILLAVET and NICHELE 1999; THIEDE 1994). Governmental support offered to subsistence agriculture was mainly done through agricultural development policies, the main objective being to have subsistence farmers participate in markets. -

The Place of Photovoltaics in Poland's Energy

energies Article The Place of Photovoltaics in Poland’s Energy Mix Renata Gnatowska * and Elzbieta˙ Mory ´n-Kucharczyk Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Computer Science, Institute of Thermal Machinery, Cz˛estochowaUniversity of Technology, Armii Krajowej 21, 42-200 Cz˛estochowa,Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-343250534 Abstract: The energy strategy and environmental policy in the European Union are climate neutrality, low-carbon gas emissions, and an environmentally friendly economy by fighting global warming and increasing energy production from renewable sources (RES). These sources, which are characterized by high investment costs, require the use of appropriate support mechanisms introduced with suitable regulations. The article presents the current state and perspectives of using renewable energy sources in Poland, especially photovoltaic systems (PV). The specific features of Polish photovoltaics and the economic analysis of investment in a photovoltaic farm with a capacity of 1 MW are presented according to a new act on renewable energy sources. This publication shows the importance of government support that is adequate for the green energy producers. Keywords: renewable energy sources (RES); photovoltaic system (PV); energy mix; green energy 1. State of Photovoltaics Development in the World The global use of renewable energy sources (RES) is steadily increasing, which is due, among other things, to the rapid increase in demand for energy in countries that have so far been less developed [1]. Other reasons include the desire of various countries to Citation: Gnatowska, R.; become self-sufficient in energy, significant local environmental problems, as well as falling Mory´n-Kucharczyk, E. -

A Language That Forgot Itself Tomasz Kamusella*

Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe Vol 13, No 4, 2014, 129-138 Copyright © ECMI 2014 This article is located at: http://www.ecmi.de/fileadmin/downloads/publications/JEMIE/2014/Kamusella.pdf A Language that Forgot Itself Tomasz Kamusella* University of St Andrews In this essay, as a background, I reflect on how the German language was liquidated in post-1945 Poland’s region of Upper Silesia where nowadays the country’s German minority is concentrated. But the main focus is on the irony that neither this language, nor a genuine German minority education system has been revived during the last quarter of a century that has elapsed since the fall of communism in 1989, despite promises to the contrary. The mystery persists. In the entry devoted to Poland in the respectable reference on the languages of the world, the Ethnologue, the number of native speakers of German living in the country is conservatively estimated at half a million.1 Until well into the 1990s German sources spoke of one million or a million and a half Germans in Poland. It is noted that the region where they live in compact areas of settlement is the countryside of Upper Silesia. But in the region the local Germans overwhelmingly communicate in the Silesian language. Silesia Superioris, Oberschlesien, Haute-Silésie, Horní Slezsko, Górny Śląsk, Felső-Szilézia—it is known by so many names, as many homelands in Central Europe were before the powers-that-be minced and fitted this part of the continent into the unbecomingly tight and too-small pantyhose of national polities, each so pure, homogenous through and through, so painfully monolingual. -

Zalacznik1.Pdf (193,7KB PDF)

Załącznik do ogłoszenia Ministra Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi z dnia ………….. 2013 r. (poz. …..) Wykaz produktów tradycyjnych wpisanych na listę produktów tradycyjnych* WOJEWÓDZTWO DOLNOŚLĄSKIE Sery i inne produkty mleczne Ser zgorzelecki Ser kozi łomnicki Kamiennogórski ser pleśniowy Mięso świeże oraz produkty mięsne Świnka pieczona po zaciszańsku Słonina marynowana z Niemczy Mięso w kawałkach niemczańskie domowe Szynka wieprzowa niemczańska Kiełbasa niemczańska Kiełbasa galicjanka z Niemczy Przysmak wołyński z Niemczy Produkty rybołówstwa, w tym ryby Karp milicki Pstrąg kłodzki Orzechy, nasiona, zboża, warzywa i owoce (przetworzone i nie) Ogórki konserwowe ścinawskie Ogórki kwaszone ślężańskie Kapusta kwaszona ślężańska Wyroby piekarnicze i cukiernicze Begle Chleb gogołowicki Ciasto z kruszonką z Ziemi Kłodzkiej Chleb chłopski z Rogowa Sobóckiego Chleb żytni domowy z Pomocnego Chleb pszenno-żytni na zakwasie z Pomocnego Miodowe pierniczki z Przemkowa Oleje i tłuszcze (masło, margaryna itp.) Masło tradycyjne Miody Miód wrzosowy z Borów Dolnośląskich Wielokwiatowy miód z Doliny Baryczy Sudecki miód gryczany Sudecki miód wielokwiatowy Miód lipowy krupiec z Ziemi Ząbkowickiej Gotowe dania i potrawy Keselica / kysielnica / kysyłycia Śląskie niebo Czarne gołąbki krużewnickie Napoje (alkoholowe i bezalkoholowe) Juha – kompot z suszonych owoców Wino śląskie Piwo książęce z Lwówka * Wykaz zawiera produkty tradycyjne, które zostały wpisane na listę produktów tradycyjnych do dnia 28 lutego 2013 r. Tłoczony sok jabłkowy z Lutyni Jabłecznik trzebnicki -

Przegląd Więziennictwa Polskiego

PRZEGLĄD WIĘZIENNICTWA POLSKIEGO Kwartalnik poświęcony zagadnieniom prawnym, kryminologicznym i penitencjarnym Nr 96 Warszawa 2017 III kwartał 2017 Wydawnictwo Centralnego Zarządu Służby Więziennej Ministerstwa Sprawiedliwości Rada Naukowa: Przewodniczący − Czesław Kłak Wiceprzewodniczący − Krzysztof Wiak Członkowie: Krzysztof Krajewski, Emil Pływaczewski, Edward Skrętowicz, Jerzy Migdał, Beata Pastwa-Wojciechowska, Teodor Szymanowski, Stefan Lelental, Brunon Hołyst, Lech K. Paprzycki, Grażyna Szczygieł, Kazimiera Juszka, Barbara Stańdo-Kawecka, Ryszard Andrzej Stefański, Katarzyna Kaczmarczyk-Kłak, Piotr Stępniak, Wojciech Zalewski, Adam Redzik, Agnieszka Lewicka-Zelent, Robert Opora, Anna Fidelus, Zbigniew Izdebski, Matthew Maycock, Doug J. Dretke, Helena Valkova, Frider Dunkel, Miklos Levay, Jacek Pomiankiewicz, Marcin Warchoł, Bartłomiej Kowalski. Redakcja kwartalnika „Przegląd Więziennictwa Polskiego” Redaktor Naczelny − Piotr Łapiński (tel. 22-640 8424), Zastępca Redaktora Naczelnego − Marcin Dudzik, Zastępca Redaktora Naczelnego − Robert Pelewicz, Redaktor językowy (język polski) − Małgorzata Nowotny, Redaktor językowy (język angielski) − Marta Kuźma, Redaktor statystyczny − Tomasz Banyś, Sekretarz Redakcji – Konrad Wierzbicki. Kontakt: Redakcja „Przeglądu Więziennictwa Polskiego”, ul. Wiśniowa 50, 02-520 Warszawa Redaktor naczelny − tel. 22-640 8424, e-mail: [email protected] Sekretarz redakcji – tel. 504-609-742, e-mail: [email protected] fax: 22 848 6268 Strona internetowa: http://www.sw.gov.pl/przeglad-wieziennictwa-polskiego Wydawca: Centralny Zarząd Służby Więziennej, 02-521 Warszawa, ul. Rakowiecka 37a. Warunki prenumeraty: „Przegląd Więziennictwa Polskiego” jest rozprowadzany drogą prenumeraty. Sprzedaż pojedynczych numerów prowadzi redakcja. Zamówienia na prenumeratę należy przesłać do redakcji i wpłacić odpowiednią kwotę na konto: Ministerstwo Sprawiedliwości CZSW, Biuro Budżetu NBP o/o Warszawa Nr 76 1010 1010 0401 5222 3100 0000 w NBP O/O W-wa. Cena jednego numeru wynosi 20 złotych, a prenumerata roczna 80 złotych. -

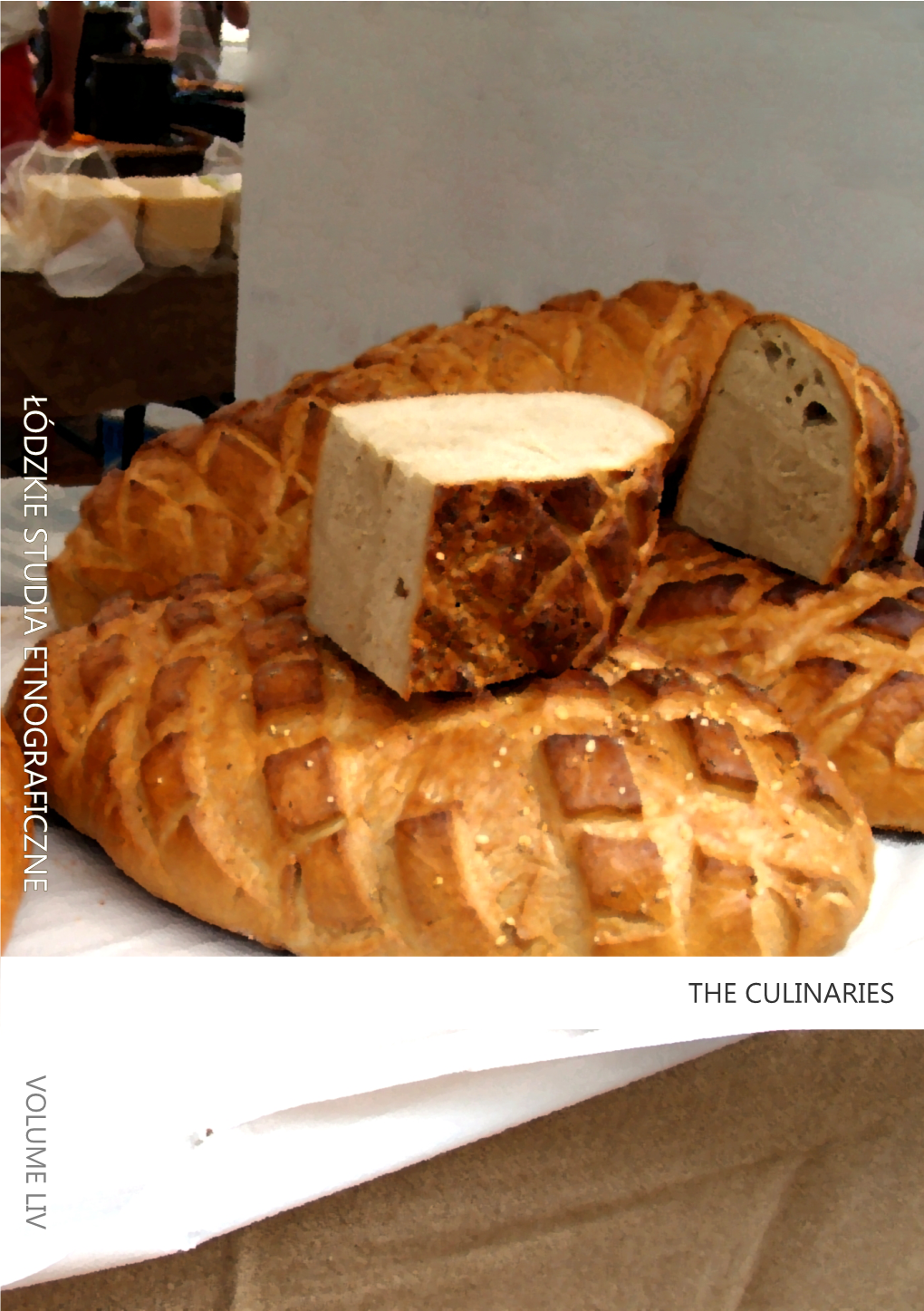

Treasures of Culinary Heritage” in Upper Silesia As Described in the Most Recent Cookbooks

Teresa Smolińska Chair of Culture and Folklore Studies Faculty of Philology University of Opole Researchers of Culture Confronted with the “Treasures of Culinary Heritage” in Upper Silesia as Described in the Most Recent Cookbooks Abstract: Considering that in the last few years culinary matters have become a fashionable topic, the author is making a preliminary attempt at assessing many myths and authoritative opinions related to it. With respect to this aim, she has reviewed utilitarian literature, to which culinary handbooks certainly belong (“Con� cerning the studies of comestibles in culture”). In this context, she has singled out cookery books pertaining to only one region, Upper Silesia. This region has a complicated history, being an ethnic borderland, where after the 2nd World War, the local population of Silesians ��ac���������������������uired new neighbours����������������������� repatriates from the ����ast� ern Borderlands annexed by the Soviet Union, settlers from central and southern Poland, as well as former emigrants coming back from the West (“‘The treasures of culinary heritage’ in cookery books from Upper Silesia”). The author discusses several Silesian cookery books which focus only on the specificity of traditional Silesian cuisine, the Silesians’ curious conservatism and attachment to their regional tastes and culinary customs, their preference for some products and dislike of other ones. From the well�provided shelf of Silesian cookery books, she has singled out two recently published, unusual culinary handbooks by the Rev. Father Prof. Andrzej Hanich (Opolszczyzna w wielu smakach. Skarby dziedzictwa kulinarnego. 2200 wypróbowanych i polecanych przepisów na przysmaki kuchni domowej, Opole 2012; Smaki polskie i opolskie. Skarby dziedzictwa kulinarnego.