View Pdf of Printed Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2003 Migration of Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds in New England

fall 2003 Migration of ruby-throated hummingbirds in new england Sharon Stichter Editor’s Note. This article is a revised and expanded version of a report that first appeared on the New England Hummers website on 10/27/03. For a fuller description of the project, please see the website at <http://www.nehummers.com>. At the site you can also sign up to be a Site Monitor for 2004. ruby-throated hummingbirds are common nesters in new england, but each year these diminutive birds travel to Mexico and central america to spend the winter. how late do they stay in new england in the fall? have the “last observed” dates been getting later in recent years? do the birds depart “all at once,” or are there ebbs and flows of migration? are there observable changes that can indicate the beginning of hummingbird migration? over the 2003 season the new england hummers research project collected data on these questions as part of a study of the migration, distribution, and population fluctuations of Archilochus colubris in our region. this report is based on three sources of information: 1) data from our site Monitors; 2) reports from the many other observers who took the time to report their sightings to new england hummers or to the state listserves Massbird, nh.birds, rI birds, and Maine-birds; and 3) the reports from hawkcount.org from two Massachusetts hawkwatch sites. our research utilizes citizen observation as its primary source of data. we now have about 50 site Monitors scattered across new england, mostly in Massachusetts and new hampshire, who keep watch on their hummingbird feeders throughout the season and report specified observations. -

Nahant Reconnaissance Report

NAHANT RECONNAISSANCE REPORT ESSEX COUNTY LANDSCAPE INVENTORY MASSACHUSETTS HERITAGE LANDSCAPE INVENTORY PROGRAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Essex National Heritage Commission PROJECT TEAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Jessica Rowcroft, Preservation Planner Division of Planning and Engineering Essex National Heritage Commission Bill Steelman, Director of Heritage Preservation Project Consultants Shary Page Berg Gretchen G. Schuler Virginia Adams, PAL Local Project Coordinator Linda Pivacek Local Heritage Landscape Participants Debbie Aliff John Benson Mark Cullinan Dan deStefano Priscilla Fitch Jonathan Gilman Tom LeBlanc Michael Manning Bill Pivacek Linda Pivacek Emily Potts Octavia Randolph Edith Richardson Calantha Sears Lynne Spencer Julie Stoller Robert Wilson Bernard Yadoff May 2005 INTRODUCTION Essex County is known for its unusually rich and varied landscapes, which are represented in each of its 34 municipalities. Heritage landscapes are those places that are created by human interaction with the natural environment. They are dynamic and evolving; they reflect the history of the community and provide a sense of place; they show the natural ecology that influenced the land use in a community; and heritage landscapes often have scenic qualities. This wealth of landscapes is central to each community’s character; yet heritage landscapes are vulnerable and ever changing. For this reason it is important to take the first steps toward their preservation by identifying those landscapes that are particularly valued by the community – a favorite local farm, a distinctive neighborhood or mill village, a unique natural feature, an inland river corridor or the rocky coast. To this end, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) and the Essex National Heritage Commission (ENHC) have collaborated to bring the Heritage Landscape Inventory program (HLI) to communities in Essex County. -

Two Unprecedented Auk Wrecks in the Northwest Atlantic in Winter 2012/13

Diamond et al.: Two auk wrecks in winter 2012/13 185 TWO UNPRECEDENTED AUK WRECKS IN THE NORTHWEST ATLANTIC IN WINTER 2012/13 ANTONY W. DIAMOND1*, DOUGLAS B. MCNAIR2, JULIE C. ELLIS3, JEAN-FRANÇOIS RAIL4, ERIN S. WHIDDEN1, ANDREW W. KRATTER5, SARAH J. COURCHESNE6, MARK A. POKRAS3, SABINA I. WILHELM7, STEPHEN W. KRESS8, ANDREW FARNSWORTH9, MARSHALL J. ILIFF9, SAMUEL H. JENNINGS3, JUSTIN D. BROWN10, JENNIFER R. BALLARD10, SARA H. SCHWEITZER11, JOSEPH C. OKONIEWSKI12, JOHN B. GALLEGOS13 & JOHN D. STANTON14 1Atlantic Laboratory for Avian Research, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, NB E3B 5A3, Canada 235 Rowell Rd., Wellfleet, MA 02667-7826, USA 3Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, Tufts University, 200 Westboro Rd., North Grafton, MA 01536, USA 4Service canadien de la faune, 801-1550 ave. d’Estimauville, QC G1J 0C3, Canada 5Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA 6Northern Essex Community College, 100 Elliot St., Haverhill, MA 01830, USA 7Canadian Wildlife Service, 6 Bruce St., Mount Pearl, NL A1N 4T3, Canada 8National Audubon Society Seabird Restoration Program, 159 Sapsucker Woods Rd., Ithaca, NY 14850, USA 9Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 159 Sapsucker Woods Rd., Ithaca, NY 14850, USA 10Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study, College of Veterinary Medicine, 501 D.W. Brooks Dr., Athens, GA 30602, USA 11North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, 1751 Varsity Dr., Raleigh, NC 27606, USA 12New York State Dept of Environmental Conservation, Wildlife Health Unit, 108 Game Farm Rd., Delmar, NY 12054, -

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County -

East Point History Text from Uniguide Audiotour

East Point History Text from UniGuide audiotour Last updated October 14, 2017 This is an official self-guided and streamable audio tour of East Point, Nahant. It highlights the natural, cultural, and military history of the site, as well as current research and education happening at Northeastern University’s Marine Science Center. Content was developed by the Northeastern University Marine Science Center with input from the Nahant Historical Society and Nahant SWIM Inc., as well as Nahant residents Gerry Butler and Linda Pivacek. 1. Stop 1 Welcome to East Point and the Northeastern University Marine Science Center. This site, which also includes property owned and managed by the Town of Nahant, boasts rich cultural and natural histories. We hope you will enjoy the tour Settlement in the Nahant area began about 10,000 years ago during the Paleo-Indian era. In 1614, the English explorer Captain John Smith reported: the “Mattahunts, two pleasant Iles of grouse, gardens and corn fields a league in the Sea from the Mayne.” Poquanum, a Sachem of Nahant, “sold” the island several times, beginning in 1630 with Thomas Dexter, now immortalized on the town seal. The geography of East Point includes one of the best examples of rocky intertidal habitat in the southern Gulf of Maine, and very likely the most-studied as well. This site is comprised of rocky headlands and lower areas that become exposed between high tide and low tide. This zone is easily identified by the many pools of seawater left behind as the water level drops during low tide. The unique conditions in these tidepools, and the prolific diversity of living organisms found there, are part of what interests scientists, as well as how this ecosystem will respond to warming and rising seas resulting from climate change. -

STATUS of the PIPING PLOVER in MASSACHUSETTS by George W. Gove, Ashland

STATUS OF THE PIPING PLOVER IN MASSACHUSETTS by George W. Gove, Ashland On January 10, 1986, the Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus) was added to the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service list of endangered and threatened species of wildlife. The entire breeding popula tion of this species in North America has been estimated at less than 2200 pairs. Piping Plovers breed in the Great Plains from southern Alberta eastward to Minnesota, the Dakotas, and Nebraska; at scattered locations around the Great Lakes; and on the Atlantic Coast from the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Maritimes to Virginia and the Carolines. They winter along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts from South Carolina to Texas and north ern Mexico. The U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service designated the Great Lakes population, which is down to less than twenty pairs, as "endangered," a term applied when extinction is imminent, and the Great Plains and Atlantic Coast populations as "threatened" (describing the state that is precursor to "endangered"). The decline of the Atlantic Coast population has been attributed to increasing recreational use and development of ocean beaches. In Massachusetts, the Piping Plover breeds coastally from Salis bury south and east to Cape Cod, the islands, and Westport. It is normally found in the state from mid-March through mid-September. This species makes a shallow nest, sometimes lined with fragments of shells, with pebbles, or wrack, along ocean beaches and filled- in areas near inlets and bays. The normal clutch of pale, sand- colored, speckled eggs is four. Incubation is underway by mid- May in Massachusetts. -

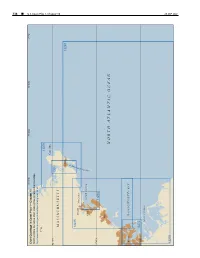

CPB1 C10 WEB.Pdf

338 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 Chapter 1, Pilot Coast U.S. 70°45'W 70°30'W 70°15'W 71°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 1—Chapter 10 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 71°W 13279 Cape Ann 42°40'N 13281 MASSACHUSETTS Gloucester 13267 R O B R A 13275 H Beverly R Manchester E T S E C SALEM SOUND U O Salem L G 42°30'N 13276 Lynn NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN Boston MASSACHUSETTS BAY 42°20'N 13272 BOSTON HARBOR 26 SEP2021 13270 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 ¢ 339 Cape Ann to Boston Harbor, Massachusetts (1) This chapter describes the Massachusetts coast along and 234 miles from New York. The entrance is marked on the northwestern shore of Massachusetts Bay from Cape its eastern side by Eastern Point Light. There is an outer Ann southwestward to but not including Boston Harbor. and inner harbor, the former having depths generally of The harbors of Gloucester, Manchester, Beverly, Salem, 18 to 52 feet and the latter, depths of 15 to 24 feet. Marblehead, Swampscott and Lynn are discussed as are (11) Gloucester Inner Harbor limits begin at a line most of the islands and dangers off the entrances to these between Black Rock Danger Daybeacon and Fort Point. harbors. (12) Gloucester is a city of great historical interest, the (2) first permanent settlement having been established in COLREGS Demarcation Lines 1623. The city limits cover the greater part of Cape Ann (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are and part of the mainland as far west as Magnolia Harbor. -

Annual Report of the Board of Harbor Commissioners, 1877 and 1878

: PUBLIC DOCUMENT .No. 33. ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Board of Harbor Commissioners FOR THE YEAR 18 7 7. BOSTON ftanb, &berg, & £0., printers to tfje CommcntntaltJ, 117 Franklin Street. 1878. ; <£ommontocaltl) of Jllaesacfjusetta HARBOR COMMISSIONERS' REPORT. To the Honorable the Senate and the Home of Representatives of the Common- wealth of Massachusetts. The Board of Harbor Commissioners, in accordance with the provisions of law, respectfully submit their annual Report. By the operation of chapter 213 of the Acts of 1877, the number of the Board was reduced from five to three members. The members of the present Board, having been appointed under the provisions of said Act, were qualified, and entered upon their duties on the second day of July. The engineers employed by the former Board were continued, and the same relations to the United States Advisory Council established. It was sought to make no change in the course of proceeding, and no interruption of works in progress or matters pending and the present Report embraces the business of the entire year. South Boston Flats. The Board is happy to announce the substantial completion of the contracts with Messrs. Clapp & Ballou for the enclosure and filling of what has been known as the Twenty-jive-acre 'piece of South Boston Flats, near the junction of the Fort Point and Main Channels, which the Commonwealth by legis- lation of 1867 (chapter 354) undertook to reclaim with mate- rial taken for the most part from the bottom of the harbor. In previous reports, more especially the tenth of the series, the twofold purpose of this work, which contemplated a har- 4 HARBOR COMMISSIONERS' REPORT. -

2016 GOMSWG Census Data Table

2016 Gulf of Maine Seabird Working Group Census Results Census Window: June 12-22 (peak of tern incubation) (Results from region-wide count period are reported here - refer to island synopsis or contact island staff for season totals) *not located in the Gulf of Maine or included in GOM totals numbers need to be verified ISLAND NAME DATE METHOD COTE ARTE ROST LETE LAGU FLEDGE/NEST N SD METHOD EGGS/NEST N SD OBSERVER NOVA SCOTIA 6/12 N 619 Julie McKnight North Brother 6/12 N 35 Julie McKnight South Brother Grassy Island 6/17 - 6/20 N 893 1.23 39 0.20 1, 3 Jen Rock Country Island (not in GOM) 6/17 - 6/20 N 581 1.18 28 0.22 1, 3 Jen Rock Season Total N 18 1.60 5 0.22 3 Jen Rock 2016 NS COAST TOTAL 619 50 2015 NS COAST TOTAL 687 0 35 0 0 2014 NS COAST TOTAL 651 44 38 0 0 2013 NS COAST TOTAL 596 50 38 0 0 2012 NS COAST TOTAL 574 50 34 0 0 2011 NS COAST TOTAL 631 60 38 0 0 2010 NS COAST TOTAL 632 54 38 0 0 * Data for The Brothers is reported as total count, with 38 roseates. 2009 NS COAST TOTAL 473 42 42 0 0 2008 NS COAST TOTAL 527 28 55 0 0 NEW BRUNSWICK ISLAND NAME DATE METHOD COTE ARTE ROST LETE LAGU FLEDGE/NEST N SD METHOD EGGS/NEST N SD OBSERVER Machias Seal Season Total NP 175 0.55 (ARTE only) 54 (ARTE only) 2,3 1.52 (ARTE only)4 (ARTE on 0.60 Stefanie Collar 2016 NB COAST TOTAL A tern census was not conducted this year, but it is estimated that there were up to 175 attempted nests island-wide, with a 2015 NB COAST TOTAL 9 141 0 0 0 probable species distribution of 94% ARTE and 6% COTE, similar to last year. -

Rte-122 Kiosk Poster Final-PAXTON

ROUTE 122 ~ LOST VILLAGES SCENIC BYWAY Petersham • Barre • Oakham • Rutland • Paxton PETERSHAM BARRE OAKHAM RUTLAND PAXTON ABOUT THE WESTERN MASS BYWAYS SYSTEM For more information about the Route 122 Scenic Byway and Western Mass Scenic Byways, please scan: Nichewaug Village White Valley Village Village of Coldbrook Springs Village of West Rutland Moore State Park, an old mill village site Nichewaug was an early name for the town of Petersham. The village existed under three names for 104 years including Clark’s Oakham was originally the west wing of Rutland; first settled by Rutland was founded in 1713 and incorporated in 1722. It is The Mill Village was established in 1747 and consisted of a Nichewaug village was in the southern section of town and was Mills and Smithville, harnessing power from the Ware River to whites in the 1740s. The town was incorporated as a district on the geographical center of Massachusetts, marked by a tree gristmill, sawmill, triphammer, tavern, and one-room school also known by some as Factory Village with its riverside grist and manufacture cotton cloth. The mill closed in 1925. DCR bought June 11, 1762, and given full town status on August 23, 1775. called the Central Tree located n the Central Tree Road. Originally house. In 1965, the site was named the Major Willard Moore ~ WESTERN MASS SCENIC BYWAYS ~ saw mills, woodshops, blacksmiths and other businesses. The village all the village properties including the company store, post office, There were two main population centers in the town: the center 12 miles square, it included parts of Paxton, Oakham, Barre, Memorial State Park. -

Land Protection Plan

Appendix G S. Maslowski/USFWS Least tern Land Protection Plan ■ Introduction and Purpose ■ Project Description ■ Refuge Purpose ■ Status of Resources to be Protected ■ Threats to the Resource ■ Action and Objectives ■ Protection Options ■ Land Protection Methods ■ Service Land Protection Policy ■ Funding for Fee or Easement Purchase ■ Coordination ■ Socioeconomic and Cultural Impacts ■ Literature Cited Land Protection Plan Appendix G. Land Protection Plan G-1 Project Description Introduction and Purpose This land protection plan (LPP) provides detailed information about the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (Service, we, our) proposal to expand Nantucket National Wildlife Refuge (Nantucket NWR, refuge) on Nantucket, Massachusetts. This LPP identifies the proposed land protection boundary for the Nantucket NWR. Working with numerous partners, we delineated 2,036 acres of biologically significant land on the island of Nantucket. These acres are encompassed by the recommended acquisition boundary established in alternative B of the Nantucket NWR Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Assessment (draft CCP/EA). We plan to protect these lands through transfers at no cost, fee-title acquisition, conservation easements, and management agreements. Of the total acreage, we recommend acquiring 206 acres in fee title through transfers at no cost, 17 acres in fee title through purchase, 1,117 acres in conservation easements, and 696 acres through management agreement. The purposes of this LPP are to: 1) Provide landowners and the public with an outline of Service policies, priorities, and protection methods for land in the project area. Amanda Boyd/USFWS Nantucket National Wildlife Refuge 2) Assist landowners in determining whether their property lies within the proposed acquisition boundary. -

THE Official Magazine of the OCEANOGRAPHY SOCIETY

OceThe OFFiciala MaganZineog OF the Oceanographyra Spocietyhy CITATION Dybas, C.L. 2011. Ripple marks—The story behind the story.Oceanography 24(3):8–13, http://dx.doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2011.84. COPYRIGHT This article has been published inOceanography , Volume 24, Number 3, a quarterly journal of The Oceanography Society. Copyright 2011 by The Oceanography Society. All rights reserved. USAGE Permission is granted to copy this article for use in teaching and research. Republication, systematic reproduction, or collective redistribution of any portion of this article by photocopy machine, reposting, or other means is permitted only with the approval of The Oceanography Society. Send all correspondence to: [email protected] or The Oceanography Society, PO Box 1931, Rockville, MD 20849-1931, USA. doWnloaded From WWW.tos.org/oceanography Ripple Marks The Story Behind the Story by CHeryL Lyn Dybas THE GULF of Maine: Between A RocK and A Hard PLace? Slack Tide for Seabirds To understand the shore, it is not enough to stand like sentinels, their craggy granite faces cliff. My gaze drifts meter by meter along an catalogue its life. Understanding comes only inviting—if you’re a seabird. For hundreds old wooden railway, its rockweed-covered when we can sense the long rhythms of earth upon hundreds of Atlantic puffins, guil- planks stretching from the waterline to a and sea that sculptured its land forms and lemots, razorbills, and other birds of the lighthouse perched high above. The railway produced the rock and sand of which it is open ocean, the welcome mat is out. The once carried supplies up and down the steep composed; when we can sense with the eye birds spend their summers on the islands, edge.