Two Unprecedented Auk Wrecks in the Northwest Atlantic in Winter 2012/13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2003 Migration of Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds in New England

fall 2003 Migration of ruby-throated hummingbirds in new england Sharon Stichter Editor’s Note. This article is a revised and expanded version of a report that first appeared on the New England Hummers website on 10/27/03. For a fuller description of the project, please see the website at <http://www.nehummers.com>. At the site you can also sign up to be a Site Monitor for 2004. ruby-throated hummingbirds are common nesters in new england, but each year these diminutive birds travel to Mexico and central america to spend the winter. how late do they stay in new england in the fall? have the “last observed” dates been getting later in recent years? do the birds depart “all at once,” or are there ebbs and flows of migration? are there observable changes that can indicate the beginning of hummingbird migration? over the 2003 season the new england hummers research project collected data on these questions as part of a study of the migration, distribution, and population fluctuations of Archilochus colubris in our region. this report is based on three sources of information: 1) data from our site Monitors; 2) reports from the many other observers who took the time to report their sightings to new england hummers or to the state listserves Massbird, nh.birds, rI birds, and Maine-birds; and 3) the reports from hawkcount.org from two Massachusetts hawkwatch sites. our research utilizes citizen observation as its primary source of data. we now have about 50 site Monitors scattered across new england, mostly in Massachusetts and new hampshire, who keep watch on their hummingbird feeders throughout the season and report specified observations. -

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County -

CPB1 C10 WEB.Pdf

338 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 Chapter 1, Pilot Coast U.S. 70°45'W 70°30'W 70°15'W 71°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 1—Chapter 10 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 71°W 13279 Cape Ann 42°40'N 13281 MASSACHUSETTS Gloucester 13267 R O B R A 13275 H Beverly R Manchester E T S E C SALEM SOUND U O Salem L G 42°30'N 13276 Lynn NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN Boston MASSACHUSETTS BAY 42°20'N 13272 BOSTON HARBOR 26 SEP2021 13270 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 ¢ 339 Cape Ann to Boston Harbor, Massachusetts (1) This chapter describes the Massachusetts coast along and 234 miles from New York. The entrance is marked on the northwestern shore of Massachusetts Bay from Cape its eastern side by Eastern Point Light. There is an outer Ann southwestward to but not including Boston Harbor. and inner harbor, the former having depths generally of The harbors of Gloucester, Manchester, Beverly, Salem, 18 to 52 feet and the latter, depths of 15 to 24 feet. Marblehead, Swampscott and Lynn are discussed as are (11) Gloucester Inner Harbor limits begin at a line most of the islands and dangers off the entrances to these between Black Rock Danger Daybeacon and Fort Point. harbors. (12) Gloucester is a city of great historical interest, the (2) first permanent settlement having been established in COLREGS Demarcation Lines 1623. The city limits cover the greater part of Cape Ann (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are and part of the mainland as far west as Magnolia Harbor. -

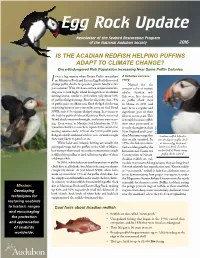

2016 Egg Rock Update

Egg Rock Update Newsletter of the Seabird Restoration Program of the National Audubon Society 2016 IS THE ACADIAN REDFISH HELPING PUFFINS ADAPT TO CLIMATE CHANGE? Once-Endangered Fish Population Increasing Near Some Puffin Colonies t was a big surprise when Project Puffin researchers A fisheries success I on Matinicus Rock and Eastern Egg Rock discovered story plump puffin chicks deep under granite boulders this Named for the past summer. With 2016 sea surface temperatures hit- crimson color of mature ting near-record highs, island biologists feared a dismal adults, Acadian red- nesting season, similar to 2013 when only about 10% fish were first detected of puffins fledged young. But the discovery that 75% in puffin chick diets of puffin pairs on Matinicus Rock fledged chicks was in Maine in 2011 and surprising because just nine miles away on Seal Island have been a regular and NWR, only 57% of pairs fledged young. In contrast to significant part of their the healthy puffin chicks at Matinicus Rock, most Seal diets in recent years. This Island chicks were underweight, and many were starv- is notable because redfish ing. Even worse, at Machias Seal Island on the U.S./ were once persecuted so Canadian border, researchers reported the worst-ever severely throughout their nesting season—only 12% of the 5,000 puffin pairs New England and Cana- Jean Hall Jean fledged a chick, and most of these were so underweight dian Maritimes range that Acadian redfish helped to they were likely to perish at sea. they nearly vanished. In save the day for puffin chicks White hake and Atlantic herring are usually the 1996, the fish was classi- at Eastern Egg Rock and principal forage fish for puffins in the Gulf of Maine, fied as endangered by the Matinicus Rock; elsewhere but warmer-than-usual sea surface temperatures made International Union for in the Gulf of Maine many puffin chicks starved. -

The Sudbury River Boater's Trail

The Sudbury River Boater’s Trail Ñ S U DB U RY ASSABET &CONCORD WILD & SCENIC R IVE R STEWARDSHIP COUNCIL COMMENTARY GUIDE BY MATTHEW EISENSON THE SUDBURY RIVER BOATer’S TRAIL From Little Farms Road (Framingham) to Old Calf Pasture/ Egg Rock (Concord) runs approximately 15 miles. It consists of three major segments, each of approximately 5 miles: 1. Little Farms Road to Route 27 2. Route 27 to the Lincoln Boat Launch on Route 117 3. Lincoln Boat Launch Route 117 to Old Calf Pasture/Egg Rock Visit www.sudbury-assabet-concord.org for more information or to request a Boater’s Trail Guide. 1. Little Farms Road to Route 27 This section of the Boater’s Trail begins in the shaded, meandering reaches of the Sudbury River and runs about 5 miles to the beginnings of the wide open flood plains in Sudbury and Wayland. Take modest precaution because the water can be quick moving in the upper portion of this section in the spring. Along the way there are many natural and historical sites of interest, including the Oxbow, a natural river feature near the put-in, and remnants of the Old Stone Bridge. The River passes to the east of Heard Pond in Wayland and enters Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge. Towards the conclusion of this section, the flood plains open in to wide meadows where there is opportunity to view numerous water birds. 2. Route 27 to Route 117, Lincoln Boat Launch on Route 117 The meadows reach their widest just downstream of Route 27. -

Northeast Region for the Deaf and Hard-Of-Hearing 1 800/877 8339 Fiscal Year 2009 State of the Refuges U.S

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 300 Westgate Center Drive U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Hadley, MA 01035 413/253 8200 Federal Relay Service Northeast Region for the deaf and hard-of-hearing 1 800/877 8339 Fiscal Year 2009 State of the Refuges U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 1 800/344 WILD http://www.fws.gov March 2010 From the Chief Regional profile: 2009 Fiscal year 2009 was a year of change and opportunity for refuges in the Operations budget: $51,000,000 Northeast Region. After several years of downsizing and reorganizing, the Full-time staff: 357 budget situation has improved. Beginning in FY2008, national wildlife refuges Number of refuges: 71 nationwide have used congressionally allocated funding increases to stabilize Designated wilderness: 20,977 acres the baseline funding for staffed refuges in the National Wildlife Refuge System. Visitors: 5,934,000 FY2009 gave us a chance to begin to rebuild. Improvements are being made in Friends groups: 56 funding and staffing our wildlife inventory and monitoring efforts, our visitor Volunteer support: 222,911 hours services work, and our administrative staffs. Utilizing savings achieved through Number of volunteers: 5,695 downsizing in prior years and new funding provided in FY2009 and FY2010 (which began on October 1, 2009) we will fill 16 new field-based positions in the Northeast Region. Land Acquisition The Northeast Region collaborates with The accomplishments of our 71 Northeast Region refuges are many and great. In friends groups, private landowners, state the areas of land protection, science and management, welcoming visitors, and and local governments and conservation employing youth, Northeast Region refuges are leading the way nationally for advocates to strategically protect land the National Wildlife Refuge System. -

Walden Planning Unit

cler Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Massachusetts Bureau of Planning and Resource Protection Resource Management Planning Program RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN Walden Planning Unit Including Walden Pond State Reservation May 2013 In coordination with: BSC GROUP CISIS Crosby I Schlessinger I Smallridge, LLC cler Massachusetts Walden Planning Unit I ncluding Walden Pond State Reservation RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2013 Deval L. Patrick, Governor Timothy P. Murray, Lt. Governor Richard K. Sullivan, Jr., Secretary Edward M. Lambert, J r., Commissioner John P. Murray, Deputy Commissioner for Park Operations Resource Management Plans (RMPs) provide guidelines for management of properties under the stewardship of the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR). They are intended to be working documents for setting priorities, enabling the Department to adapt to changing fiscal, social, and environmental conditions. The planning process provides a forum for communication and cooperation with park visitors and the surrounding communities to ensure transparency in the DCR's stewardship efforts. One of the most recognizable properties in the DCR park system, Walden Pond State Reservation is an iconic national and international destination. The pond that inspired Henry David Thoreau's seminal work Walden, or Life in the Woods holds divergent meanings. To many, the reservation is a sacred landscape and international cultural heritage site. To some, it is a profound symbol of both Thoreau's writings and the genesis of the land conservation movement. Simultaneously, the reservation is valued for its recreation opportunities, whether swimming in Walden Pond's waters on hot summer days, canoeing on the pond's calm waters, or cross-country skiing in its surrounding forests. -

Invitation to Qualified Candidates INTRODUCTION

THE TOWN OF CONCORD, MA TOWN MANAGER RECRUITMENT Invitation to Qualified Candidates INTRODUCTION The Concord Town Manager position provides a seasoned manager with an ideal career opportunity in a “classic” New England town. Over 240 years ago the residents of Concord played a pivotal role in the American Revolution and today its residents still honor that historic tradition with grass roots democracy and a revolutionary spirit. The ideal candidate will be met with a progressive community steeped in both citizen leadership and professional management and with values that transcend the test of time. The Town is administered by an Open Town Meeting, Select Board and Town Manager form of government and over 250 citizens serving on over 40 boards, committees or commissions. Public participation is a core value in Concord. This profile is a resource for interested candidates, however all are encouraged to do their own research. Valuable information is provided here along with links to important websites so that potential candidates can consider their “fit” in the Concord community. Submission information can be found by visiting Municipal Resources’ website. ABOUT CONCORD The Town of Concord, MA is located in Middlesex County, 17 miles northwest from Boston, just west of the intersection of Route 128 and Route 2. Concord has a population of 17,000 residents with 6,500 households and a land area of 26 square miles. This is a predominately residential community with three vibrant business districts: Concord Center at Main and Walden Streets, on Thoreau Street near the train station and in West Concord at the second rail station. -

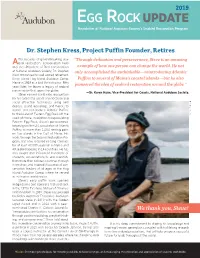

2019 Egg Rock UPDATE Newsletter of National Audubon Society’S Seabird Restoration Program

2019 EGG ROCK UPDATE Newsletter of National Audubon Society’s Seabird Restoration Program Dr. Stephen Kress, Project Puffin Founder, Retires fter decades of groundbreaking sea- “Through dedication and perseverance, Steve is an amazing Abird restoration, conservation hero and Vice-President of Bird Conservation example of how one person can change the world. He not at National Audubon Society, Dr. Stephen only accomplished the unthinkable—reintroducing Atlantic Kress announced his well-earned retirement. Steve joined Hog Island Audubon Camp, Puffins to several of Maine’s coastal islands—but he also Maine in 1969 as a bird life instructor. Fifty years later, he leaves a legacy of seabird pioneered the idea of seabird restoration around the globe.” conservation that spans the globe. —Dr. Karen Hyun, Vice-President for Coasts, National Audubon Society. Steve earned worldwide recognition for his successful use of translocation and R social attraction techniques using bird YAN D decoys, sound recordings, and mirrors to AVI D B attract and reintroduce Atlantic Puffins R IOWN to the island of Eastern Egg Rock off the coast of Maine. In addition to repopulating Eastern Egg Rock, Steve’s perseverance helped grow the U.S. population of Atlantic Puffins to more than 1,000 nesting pairs on five islands in the Gulf of Maine. His work, through the Seabird Restoration Pro- gram, has now restored nesting colonies for at least 42,000 seabirds in Maine and 49 seabird species in 14 countries. He has also taught and influenced hundreds of students, conservationists, and scientists from more than a dozen countries through internships, and inspired thousands of con- servation leaders of all ages at the Hog Island Audubon Camp, where he served as instructor and director. -

Table 1. Results of the 1994-95 Massachusetts Coastal Colonial

Table 1. Results of the 1994-95 Massachusetts Coastal Colonial Waterbird Inventory showing estimated numbers of pairs for all species at all colonies located in the coastal zone. An asterisk (*) indicates "count not taken." Data compiled by B.G. Blodget, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. COLONY SPECIES NO. OF PAIRS CENSUS REPORTING NUMBER COLONY NAME, TOWN CODE 1994 1995 METHOD1 AUTHORITY 324007.0 Woodbridge I., Newburyport COTE 65 62 ACG FWS 324007.1 Blackwater R. Group, Salisbury 0 0 TTOR 324007.2 Chaces I., Newbury COTE 14 0 ACG FWS HEGU 0 1 NCG FWS 324008.0 Plum I. R. Group, Newbury COTE 34 30 NCG FWS 324009.0 Parker R. Group, Newbury COTE 10 15 NCG FWS 324009.1 Plum I. Beach, Newbury-Rowley-Ip LETE 32 19 NCG FWS 324010.0 Roger I., Ipswich COTE 6 2 ACB ECG 324010.1 Stage I.-Cross Hill F., Ipswich * 0 FWS 324010.2 Bagwell I., Ipswich COTE 8 8 ACB ECG 324010.3 Rowley Salt Marshes, Rowley COTE 3 2 ACB ECG 324010.4 Lord's I., Ipswich COTE 25 20 ACB ECG 324010.5 Ipswich Salt Marshes, Ipswich COTE 13 13 ACB ECG 324011.0 Crane Beach, Ipswich LETE 30 75 NCG TTOR 324012.0 Tenpound I., Gloucester HEGU 75 * NCG DFW GBBG 70 * NCG DFW 324013.0 Norman's Woe, Gloucester DCCO 199 * NCG DFW HEGU 76 * NCG DFW TABLE 1... 2 COLONY SPECIES NO. OF PAIRS CENSUS REPORTING NUMBER COLONY NAME, TOWN CODE 1994 1995 METHOD AUTHORITY GBBG 4 * NCG DFW 324014.0 Kettle I., Gloucester GREG 42 * NCG DFW SNEG 207 * NCG DFW LBHE 6 * NCG DFW BCNH 7 * NCG DFW GLIB 35 * NCG DFW HEGU 388 * NCG DFW GBBG 146 * NCG DFW 324015.0 Graves I., Manchester HEGU 97 * NCG DFW GBBG 74 * NCG DFW 324016.0 Great Egg Rock, Manchester DCCO 124 * NCB DFW GBBG 2 * NCB DFW 324017.0 Dry Salvages, Rockport DCCO * 19 NCG DFW 324018.0 Straitsmouth I., Rockport HEGU 23 * NCG MAS GBBG 143 * NCG MAS 324019.0 Thacher I., Rockport BCNH 1 1 NCG DFW GLIB 0 1 AEG DFW HEGU 1,185 1,359 NCG FWS TABLE 1.. -

Family-Friendly River Map (PDF)

Bring your family to enjoy the Sudbury, Assabet, & Concord Rivers Use this guide to pick an adventure that’s suitable for the whole family on the Wild and Scenic Sudbury, Assabet, and Concord Rivers. Middlesex Canal Museum Minute Man Wolbach Farm 17 Faulkner St., North Billerica National Historical Park 18 Wolbach Rd., Sudbury Open on weekend afternoons and weekdays Liberty St., Concord Home to Sudbury Valley Trustees, Wolbach by appointment, the Middlesex Canal Across the river from the Old Manse, the Farm is a 54-acre property along the Museum is a small museum that preserves Park commemorates the beginning of the Sudbury River. The Farm is a great place to and commemorates the history of the Revolutionary War. There are wide open explore local history and natural areas. The Middlesex Canal. The museum is located in fields with easily walkable trails and beau- Nature Nook in the main building provides a portion of the old Faulkner Mills complex tiful views. Historic buildings and a visitor interactive displays and crafts designed to and contains maps and artifacts from the center offer many learning opportunities. teach children and families about wildlife canal and mills. North Bridge crosses the Concord River and found on the Farm. is a fun place to watch boats go by. Vietnam Veterans Park Great Meadows National Treble Cove Rd., Billerica Old Calf Pasture/Egg Rock Wildife Refuge—Pelham Island Located by Wining Pond, Billerica’s Veterans Lowell Rd., Concord Pelham Island Rd., Wayland Park offers playgrounds, soccer fields, plenty Off Lowell Road there is a boat launch The short Griscom Trail offers a walk that of walking trails, and opportunities for fishing.* and a short trail along the river ending at wends through forests and looks out over the a point where the Assabet and Sudbury Sudbury River floodplain. -

Freedom's Way National Heritage Area Management Plan

Freedom’s Way National Heritage Area Management Plan Freedom’s Way Heritage Association, Inc. Massachusetts and New Hampshire June 2015 Photos, front cover: Background—the view of Mount Wachusett on the southwestern edge of the Freedom’s Way National Heritage Area from Prospect Hill and Fruitlands National Register Historic District in Harvard, MA, at roughly the center of the heritage area. Detail, from left—Amherst, NH, town common; the Old North Bridge, center of the Concord, MA, portion of the fight in the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, today in the Minute Man National Historical Park operated by the National Park Service and a key Freedom’s Way partner; gazebo in Ashby, MA; and a costumed interpreter with visitors at the town common in Lexington, MA, known as Battle Green and a National Historic Landmark. All photos are by Patrice Todisco, Interim Executive Director of the Freedom’s Way Heritage Association. Freedom’s Way National Heritage Area Management Plan June 2015 Freedom’s Way Heritage Association, Inc. Massachusetts and New Hampshire Prepared by ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Board of Directors of Freedom’s Way Heritage Association, Inc. Meg Bagdonas, President Tim Castner PAST DIRECTORS Will Ludt, Vice-President Marge Darby Robert Adam Margaret Coppe, Secretary Anne DeBoalt May Balsama Paul Przybyla, Treasurer Wyona Lynch-McWhite Sharon Bernard Peter C. Webb, Executive Denise Morrissey Hugh Field Committee Member-at- Charles Worcester Large Management Plan Steering Committee Maud Ayson Will Ludt Patrice Todisco Meg Bagdonas Denise Morrissey Lucy Wallace May Balsama Heidi Ricci Peter C. Webb Marge Darby Lou Sideris Interpretive Plan Review Committee Maud Ayson Phil Lupsiewicz Mary Fuhrer Leslie Obleschuck Jayne Gordon Patrice Todisco Freedom’s Way Heritage Association Team Patrice Todisco, Interim Executive Director Mary Fuhrer, Historian & Consultant, Maud Ayson, Program Coordinator Paths of the Patriots Linda Bowie, Communications Manager Kim Trang Nguyen, Office Manager WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO: U.S.