Inland and Coastal Wetlands of Massachusetts: Status and Trends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Samoa

A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania In: Scott, D.A. (ed.) 1993. A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania. IWRB, Slimbridge, U.K. and AWB, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania WESTERN SAMOA INTRODUCTION by Cedric Schuster Department of Lands and Environment Area: 2,935 sq.km. Population: 170,000. Western Samoa is an independent state in the South Pacific situated between latitudes 13° and 14°30' South and longitudes 171° and 173° West, approximately 1,000 km northeast of Fiji. The state comprises two main inhabited islands, Savai'i (1,820 sq.km) and Upolu (1,105 sq.km), and seven islets, two of which are inhabited. Western Samoa is an oceanic volcanic archipelago that originated in the Pliocene. The islands were formed in a westerly direction with the oldest eruption, the Fagaloa volcanics, on the eastern side. The islands are still volcanically active, with the last two eruptions being in 1760 and 1905-11 respectively. Much of the country is mountainous, with Mount Silisili (1,858 m) on Savai'i being the highest point. Western Samoa has a wet tropical climate with temperatures ranging between 17°C and 34°C and an average temperature of 26.5°C. The temperature difference between the rainy season (November to March) and the dry season (May to October) is only 2°C. Rainfall is heavy, with a minimum of 2,000 mm in all places. The islands are strongly influenced by the trade winds, with the Southeast Trades blowing 82% of the time from April to October and 54% of the time from May to November. -

PLTA-0103 Nature Conservancy 3/19/04 4:00 PM Page 1

PLTA-0103 Nature Conservancy 3/19/04 4:00 PM Page 1 ............................................................. Pennsylvania’s Land Trusts The Nature Conservancy About Land Trusts Conservation Options Conserving our Commonwealth Pennsylvania Chapter Land trusts are charitable organizations that conserve land Land trusts and landowners as well as government can by purchasing or accepting donations of land and conservation access a variety of voluntary tools for conserving special ................................................................ easements. Land trust work is based on voluntary agreements places. The basic tools are described below. The privilege of possessing Produced by the the earth entails the Pennsylvania Land Trust Association with landowners and creating projects with win-win A land trust can acquire land. The land trust then responsibility of passing it on, working in partnership with outcomes for communities. takes care of the property as a wildlife preserve, the better for our use, Pennsylvania’s land trusts Nearly a hundred land trusts work to protect important public recreation area or other conservation purpose. not only to immediate posterity, but to the unknown future, with financial support from the lands across Pennsylvania. Governed by unpaid A landowner and land trust may create an the nature of which is not William Penn Foundation, Have You Been to the Bog? boards of directors, they range from all-volunteer agreement known as a conservation easement. given us to know. an anonymous donor and the groups working in a single municipality The easement limits certain uses on all or a ~ Aldo Leopold Pennsylvania Department of Conservation n spring days, the Tannersville Cranberry Bog This kind of wonder saved the bog for today and for to large multi-county organizations with portion of a property for conservation and Natural Resources belongs to fourth-graders. -

Lowland Raised Bog (UK BAP Priority Habitat Description)

UK Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Habitat Descriptions Lowland Raised Bog From: UK Biodiversity Action Plan; Priority Habitat Descriptions. BRIG (ed. Ant Maddock) 2008. This document is available from: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-5706 For more information about the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) visit http://www.jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-5155 Please note: this document was uploaded in November 2016, and replaces an earlier version, in order to correct a broken web-link. No other changes have been made. The earlier version can be viewed and downloaded from The National Archives: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20150302161254/http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page- 5706 Lowland Raised Bog The definition of this habitat remains unchanged from the pre-existing Habitat Action Plan (https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110303150026/http://www.ukbap.org.uk/UKPl ans.aspx?ID=20, a summary of which appears below. Lowland raised bogs are peatland ecosystems which develop primarily, but not exclusively, in lowland areas such as the head of estuaries, along river flood-plains and in topographic depressions. In such locations drainage may be impeded by a high groundwater table, or by low permeability substrata such as estuarine, glacial or lacustrine clays. The resultant waterlogging provides anaerobic conditions which slow down the decomposition of plant material which in turn leads to an accumulation of peat. Continued accrual of peat elevates the bog surface above regional groundwater levels to form a gently-curving dome from which the term ‘raised’ bog is derived. The thickness of the peat mantle varies considerably but can exceed 12m. -

Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries

E3: ECOSYSTEMS, ENERGY FLOW, & EDUCATION Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries Eco-systems, Energy Flow, and Education: Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries CONTENT OUTLINE Big Idea / Objectives / Driving Questions 3 Selby Gardens’ Field Study Opportunities 3 - 4 Background Information: 5 - 7 What is an Estuary? 5 Why are Estuaries Important? 5 Why Protect Estuaries? 6 What are Mangrove Wetlands? 6 Why are Mangrove Wetlands Important? 7 Endangered Mangroves 7 Grade Level Units: 8 - 19 8 - 11 (K-3) “Welcome to the Wetlands” 12 - 15 (4-8) “A Magnificent Mangrove Maze” 16 - 19 (7-12) “Monitoring the Mangroves” Educator Resources & Appendix 20 - 22 2 Eco-systems, Energy Flow, and Education: Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries GRADE LEVEL: K-12 SUBJECT: Science (includes interdisciplinary Common Core connections & extension activities) BIG IDEA/OBJECTIVE: To help students broaden their understanding of the Coastal Wetlands of Southwest Florida (specifically focusing on estuaries and mangroves) and our individual and societal interconnectedness within it. Through completion of these units, students will explore and compare the unique contributions and environmental vulnerability of these precious ecosystems. UNIT TITLES/DRIVING QUESTIONS: (Please note: many of the activities span a range of age levels beyond that specifically listed and can be easily modified to meet the needs of diverse learners. For example, the bibomimicry water filtration activity can be used with learners of all ages. Information on modification for -

Guide for Constructed Wetlands

A Maintenance Guide for Constructed of the Southern WetlandsCoastal Plain Cover The constructed wetland featured on the cover was designed and photographed by Verdant Enterprises. Photographs Photographs in this books were taken by Christa Frangiamore Hayes, unless otherwise noted. Illustrations Illustrations for this publication were taken from the works of early naturalists and illustrators exploring the fauna and flora of the Southeast. Legacy of Abundance We have in our keeping a legacy of abundant, beautiful, and healthy natural communities. Human habitat often closely borders important natural wetland communities, and the way that we use these spaces—whether it’s a back yard or a public park—can reflect, celebrate, and protect nearby natural landscapes. Plant your garden to support this biologically rich region, and let native plant communities and ecologies inspire your landscape. A Maintenance Guide for Constructed of the Southern WetlandsCoastal Plain Thomas Angell Christa F. Hayes Katherine Perry 2015 Acknowledgments Our thanks to the following for their support of this wetland management guide: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (grant award #NA14NOS4190117), Georgia Department of Natural Resources (Coastal Resources and Wildlife Divisions), Coastal WildScapes, City of Midway, and Verdant Enterprises. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge The Nature Conservancy & The Orianne Society for their partnership. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of DNR, OCRM or NOAA. We would also like to thank the following professionals for their thoughtful input and review of this manual: Terrell Chipp Scott Coleman Sonny Emmert Tom Havens Jessica Higgins John Jensen Christi Lambert Eamonn Leonard Jan McKinnon Tara Merrill Jim Renner Dirk Stevenson Theresa Thom Lucy Thomas Jacob Thompson Mayor Clemontine F. -

Rte-122 Kiosk Poster Final-PAXTON

ROUTE 122 ~ LOST VILLAGES SCENIC BYWAY Petersham • Barre • Oakham • Rutland • Paxton PETERSHAM BARRE OAKHAM RUTLAND PAXTON ABOUT THE WESTERN MASS BYWAYS SYSTEM For more information about the Route 122 Scenic Byway and Western Mass Scenic Byways, please scan: Nichewaug Village White Valley Village Village of Coldbrook Springs Village of West Rutland Moore State Park, an old mill village site Nichewaug was an early name for the town of Petersham. The village existed under three names for 104 years including Clark’s Oakham was originally the west wing of Rutland; first settled by Rutland was founded in 1713 and incorporated in 1722. It is The Mill Village was established in 1747 and consisted of a Nichewaug village was in the southern section of town and was Mills and Smithville, harnessing power from the Ware River to whites in the 1740s. The town was incorporated as a district on the geographical center of Massachusetts, marked by a tree gristmill, sawmill, triphammer, tavern, and one-room school also known by some as Factory Village with its riverside grist and manufacture cotton cloth. The mill closed in 1925. DCR bought June 11, 1762, and given full town status on August 23, 1775. called the Central Tree located n the Central Tree Road. Originally house. In 1965, the site was named the Major Willard Moore ~ WESTERN MASS SCENIC BYWAYS ~ saw mills, woodshops, blacksmiths and other businesses. The village all the village properties including the company store, post office, There were two main population centers in the town: the center 12 miles square, it included parts of Paxton, Oakham, Barre, Memorial State Park. -

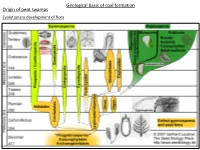

Geological Basis of Coal Formation Origin of Peat Swamps Evolutionary Development of Flora

Geological basis of coal formation Origin of peat swamps Evolutionary development of flora Peat swamp forests are tropical moist forests where waterlogged soil prevents dead leaves and wood from fully decomposing. Over time, this creates a thick layer of acidic peat. Large areas of these forests are being logged at high rates. True coal-seam formation took place only after Middle and Upper Devonian, when the plants spread over continent very rapidly. Devonian coal seams don’t have any economic value. The Devonian period was a time of great tectonic activity, as Euramerica and Gondwana drew closer together. The continent Euramerica (or Laurassia) was created in the early Devonian by the collision of Laurentia and Baltica, which rotated into the natural dry zone along the Tropic of Capricorn, which is formed as much in Paleozoic times as nowadays by the convergence of two great air-masses, the Hadley cell and the Ferrel cell. In these near- deserts, the Old Red Sandstone sedimentary beds formed, made red by the oxidized iron (hematite) characteristic of drought conditions. Sea levels were high worldwide, and much of the land lay under shallow seas, where tropical reef organisms lived. The deep, enormous Panthalassa (the "universal Devonian Paleogeography ocean") covered the rest of the planet. Other minor oceans were Paleo-Tethys, Proto- Tethys, Rheic Ocean, and Ural Ocean (which was closed during the collision with Siberia and Baltica). Carboniferous flora Upper Carboniferous is known as bituminous coal period. 30 m 7 m Permian coal deposits formed predominantly from Gymnosperm Cordaites. Cretaceous and Tertiary peats were formed from angiosperm floras. -

Strangmoor Bog the Unique Formation of Seney’S Natural National Landmark

Strangmoor Bog The Unique Formation of Seney’s Natural National Landmark Photo of a Strangmoor Bog, or String Bog, Seney NWR Schoolcraft County. Photo Courtesy of Josh Cohn—MNFI Seney National Wildlife Refuge, Schoolcraft County - Landmarks are a way to mark our path – easily recognizable, they prevent us from getting lost. From signs on a well-worn trail to the corner store in your neighborhood, landmarks can point us in the right direction. Landmarks are also how we mark our cultural identity and celebrate our past. We can erect a stature to honor a famous person’s work or build a monument to remind us of an important event. Landmarks - based on location or time - help us find our way. The National Natural Landmark Program “The patterned peat bog Natural landmarks are just as crucial and important for marking our within the National Natural paths and history, but instead of humans building a statue or monument to commemorate something, nature has already built Landmark at Seney marks the them. Through the National Natural Landmarks Program, the southern limit of patterned federal government recognizes and cares for natural landmarks, sites that contain rare geological features or plant and animal life. bogs in North America and is the largest and most striking The Secretary of the Interior designates these natural landmarks based on a number of traits: diversity, character, value to science example in Michigan and the and education, condition and rarity. Once designated, the National Lower 48 states..” Park Service administers the program, collaborating with landowners and other partners to conserve the nation’s natural heritage. -

Boreal Wetlands, Bogs

boreal wetlands Bogs Treed Bog Bogs Bogs are peatlands that have deep deposits (>40 cm) of poorly decomposed organic material (referred to as peat). They are elevated above the surrounding terrain and receive water and most nutrients from precipitation. Bogs are the most nutrient-poor wetlands in the western boreal forest. Shrubby Bog Ecological Benefits Types of Bogs j Due to deep organic deposits, bogs store j Treed Bog: Sparsely vegetated and large amounts of carbon and help to stunted (<10 m) black spruce with moderate climate change sphagnum moss and low-lying shrubs j Important habitat for the threatened woodland caribou j Shrubby Bog: Low-lying shrubs j Important water storage/recharge areas and sphagnum moss on the landscape that release water in dry periods and store water in wet j Open Bog: sphagnum moss dominated Open Bog periods with sparse non-woody vegetation ducks.ca boreal wetlands Bogs Treed Bog (note >25-60% canopy closure) b black spruce b c bog cranberry d sphagnum moss e Labrador tea f cloudberry Sphagnum Moss e f c d Identifying Characteristics organic matter Vegetation water table mineral soil j Low plant diversity due to lack of nutrients 0 j Tree and ground lichens can be abundant 20 j Treed Bog: stunted black spruce acrotem 40 (25- 60% canopy closure) with sphagnum moss ground cover (>20%) 60 j Shrubby Bog: low-lying shrubs (e.g. 80cm catotelm Solitary Sandpiper Labrador tea, bog cranberry >25%) with Soil sphagnum moss (>20%) tree cover <25% j Peat deposits (> 40 cm) accumulating over j Open Bog: sphagnum moss -

Ocm08732575-1946.Pdf

July 1, 1946 To the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives in General Court 'Assembled: The Massachusetts State Planning Board herewith submits its re port for the' fiscal year ending June 30, '1946. One change occurred during the year in the Board membership. Richard H. Edwards, who was appointed to fill the unexpired term occa sioned by the death of Frederic H. Fay in 1944, rendered brief bu.t con structive service until October 1945 when he was succeeded by Robert C. Nordblom who was appointed for the six-year period ending September 18, 1951. For purposes of- convonience in carrying fonm,rd its dotailed studies, the Board has divided tho State into sevon planning regions as follows: 1. Berkshire Region including all of BerkshJre County (two cities and thirty towns) 2. Connecticut Valley Region including all of Franklin, Hampshire and Hampden Counties (f:'ve cities and sixtJ-~our tmms) 3. Worcester County Region includi~ all of Worcester County plus eight adjoining towns in Middlesex County (five cities and sj.xty-three towns) 4. Merr:1mac Region (throe cities and twenty-four towns) 5. Massachusetts Bay and Environs (nineteen citiefl and eighty-one towns) 6. Bristol-Plymouth Region (five cities and twenty-seven towns) 7. Cape Region including Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket Is lands (twenty-three towns), These seven rogions together comprise the thirty-nlne cities and three hundred and twelve towns totaling threo hund.red and fifty-one muni cipaJJ,tios in the Commonwealth. Within these regiono studiea are being carri~ covering all the elements of a comprehonoive plan. -

Great Sidney Bog Beginning with Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance Habitat Great Sidney Bog

Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance: Great Sidney Bog Beginning with Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance Habitat Great Sidney Bog Biophysical Region • Central Maine Embayment WHY IS THIS AREA SIGNIFICANT? Rare and Exemplary Because of its size, vegetation, and relatively undisturbed Natural Communities nature, the Great Sidney Bog is considered a very good Raised Level Bog Ecosystem example of a Raised Level Bog Ecosystem. Its ecological importance is augmented by its location in the southern Significant Wildlife Habitats Inland Wading Bird and Waterfowl third of the state, where raised bogs become much Deer Wintering Area scarcer than they are further north. The easy access to this peatland in the Waterville – Augusta area enhances its value for education and research. OPPORTUNITIES FOR CONSERVATION » Educate recreational users about the ecological and economic benefits provided by the focus area. » Encourage best management practices for forestry, vegetation clearing, and soil disturbance activities near significant features. » Maintain intact forested buffers along water bodies and wetlands. » Work with landowners to encourage sustainable for- est management and mining practices on remaining privately owned forest lands. » Work with willing landowners to permanently protect undeveloped areas and significant features. For more conservation opportunities, visit the Beginning with Habitat Online Toolbox: www.beginningwithhabitat. org/toolbox/about_toolbox.html. Photo credits, top to bottom: Maine Natural Areas Program, Lisa St. Hilaire (photos 4-5) 1 Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance: Great Sidney Bog Great Sidney Bog, Maine Natural Areas Program FOCUS AREA OVERVIEW Great Sidney Bog is a 605-acre Raised Level Bog lying between parts of level bogs are somewhat raised (though not domed), the Belgrade Lakes chain and the Kennebec River. -

Lowland Raised Bogs

SCOTTISH INVERTEBRATE HABITAT MANAGEMENT Lowland raised bogs Wester Moss © Paul Kirkland / Butterfly Conservation Introduction Scottish records of the Bilberry pug moth (Pasiphila debiliata ) is from Kirkconnell Flow There has been a dramatic decline in the area of (Dumfries and Galloway) while the Bog sun- lowland raised bog habitat in the past 100 years. jumper spider ( Heliophanus dampfi ) is known The area of lowland raised bog in the UK only from two sites in the UK – one of which is retaining a largely undisturbed surface is Flanders Moss (Stirlingshire). In addition, there is estimated to have diminished by around 94% a possibility that the Bog chelifer ( Microbisium from an original 95,000 ha to 6,000 ha. In brevifemoratum ) is likely to occur in Scottish Scotland, it is estimated that the original 28,000 bogs—highlighting that there may yet be ha of lowland raised bog habitat has now unrecorded species in this important habitat diminished to a current 2,500 ha. Most of the (Legg, 2010). remaining lowland raised bog in Scotland is Support for management described in this located in the central and north-east lowlands. document is available through the Scotland Rural Historically the greatest decline has occurred Development Programme (SRDP) Rural through agricultural intensification, afforestation Development Contracts (RDC). A summary of and commercial peat extraction. Future decline is this support (at time of publication) can be found likely to be the result of the gradual desiccation of in this document. bogs, damaged by a range of drainage activities and/or a general lowering of groundwater tables. Lowland raised bogs support many rare and localised invertebrates, such as the Large heath butterfly (Coenonympha tullia ) and the 6 spotted pot beetle ( Cryptocephalus sexpunctatus ).