Lowland Raised Mire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cooper's Hill Pond 1 (Josh Hellon)

Photo: Cooper’s Hill Pond 1 (Josh Hellon) 1 Contents 1 Summary ................................................................................................................................................ 2 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 3 3 Methodology ......................................................................................................................................... 4 4 Results ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Site description ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Invertebrate & plant survey ................................................................................................................ 5 5 Conclusions ........................................................................................................................................... 5 6 References ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Appendices ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Appendix 1 species lists and index calculation ........................................................................... -

Western Samoa

A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania In: Scott, D.A. (ed.) 1993. A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania. IWRB, Slimbridge, U.K. and AWB, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania WESTERN SAMOA INTRODUCTION by Cedric Schuster Department of Lands and Environment Area: 2,935 sq.km. Population: 170,000. Western Samoa is an independent state in the South Pacific situated between latitudes 13° and 14°30' South and longitudes 171° and 173° West, approximately 1,000 km northeast of Fiji. The state comprises two main inhabited islands, Savai'i (1,820 sq.km) and Upolu (1,105 sq.km), and seven islets, two of which are inhabited. Western Samoa is an oceanic volcanic archipelago that originated in the Pliocene. The islands were formed in a westerly direction with the oldest eruption, the Fagaloa volcanics, on the eastern side. The islands are still volcanically active, with the last two eruptions being in 1760 and 1905-11 respectively. Much of the country is mountainous, with Mount Silisili (1,858 m) on Savai'i being the highest point. Western Samoa has a wet tropical climate with temperatures ranging between 17°C and 34°C and an average temperature of 26.5°C. The temperature difference between the rainy season (November to March) and the dry season (May to October) is only 2°C. Rainfall is heavy, with a minimum of 2,000 mm in all places. The islands are strongly influenced by the trade winds, with the Southeast Trades blowing 82% of the time from April to October and 54% of the time from May to November. -

PLTA-0103 Nature Conservancy 3/19/04 4:00 PM Page 1

PLTA-0103 Nature Conservancy 3/19/04 4:00 PM Page 1 ............................................................. Pennsylvania’s Land Trusts The Nature Conservancy About Land Trusts Conservation Options Conserving our Commonwealth Pennsylvania Chapter Land trusts are charitable organizations that conserve land Land trusts and landowners as well as government can by purchasing or accepting donations of land and conservation access a variety of voluntary tools for conserving special ................................................................ easements. Land trust work is based on voluntary agreements places. The basic tools are described below. The privilege of possessing Produced by the the earth entails the Pennsylvania Land Trust Association with landowners and creating projects with win-win A land trust can acquire land. The land trust then responsibility of passing it on, working in partnership with outcomes for communities. takes care of the property as a wildlife preserve, the better for our use, Pennsylvania’s land trusts Nearly a hundred land trusts work to protect important public recreation area or other conservation purpose. not only to immediate posterity, but to the unknown future, with financial support from the lands across Pennsylvania. Governed by unpaid A landowner and land trust may create an the nature of which is not William Penn Foundation, Have You Been to the Bog? boards of directors, they range from all-volunteer agreement known as a conservation easement. given us to know. an anonymous donor and the groups working in a single municipality The easement limits certain uses on all or a ~ Aldo Leopold Pennsylvania Department of Conservation n spring days, the Tannersville Cranberry Bog This kind of wonder saved the bog for today and for to large multi-county organizations with portion of a property for conservation and Natural Resources belongs to fourth-graders. -

Ecology of Freshwater and Estuarine Wetlands: an Introduction

ONE Ecology of Freshwater and Estuarine Wetlands: An Introduction RebeCCA R. SHARITZ, DAROLD P. BATZER, and STeveN C. PENNINGS WHAT IS A WETLAND? WHY ARE WETLANDS IMPORTANT? CHARACTERISTicS OF SeLecTED WETLANDS Wetlands with Predominantly Precipitation Inputs Wetlands with Predominately Groundwater Inputs Wetlands with Predominately Surface Water Inputs WETLAND LOSS AND DeGRADATION WHAT THIS BOOK COVERS What Is a Wetland? The study of wetland ecology can entail an issue that rarely Wetlands are lands transitional between terrestrial and needs consideration by terrestrial or aquatic ecologists: the aquatic systems where the water table is usually at or need to define the habitat. What exactly constitutes a wet- near the surface or the land is covered by shallow water. land may not always be clear. Thus, it seems appropriate Wetlands must have one or more of the following three to begin by defining the wordwetland . The Oxford English attributes: (1) at least periodically, the land supports predominately hydrophytes; (2) the substrate is pre- Dictionary says, “Wetland (F. wet a. + land sb.)— an area of dominantly undrained hydric soil; and (3) the substrate is land that is usually saturated with water, often a marsh or nonsoil and is saturated with water or covered by shallow swamp.” While covering the basic pairing of the words wet water at some time during the growing season of each year. and land, this definition is rather ambiguous. Does “usu- ally saturated” mean at least half of the time? That would This USFWS definition emphasizes the importance of omit many seasonally flooded habitats that most ecolo- hydrology, soils, and vegetation, which you will see is a gists would consider wetlands. -

Lowland Raised Bog (UK BAP Priority Habitat Description)

UK Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Habitat Descriptions Lowland Raised Bog From: UK Biodiversity Action Plan; Priority Habitat Descriptions. BRIG (ed. Ant Maddock) 2008. This document is available from: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-5706 For more information about the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) visit http://www.jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-5155 Please note: this document was uploaded in November 2016, and replaces an earlier version, in order to correct a broken web-link. No other changes have been made. The earlier version can be viewed and downloaded from The National Archives: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20150302161254/http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page- 5706 Lowland Raised Bog The definition of this habitat remains unchanged from the pre-existing Habitat Action Plan (https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110303150026/http://www.ukbap.org.uk/UKPl ans.aspx?ID=20, a summary of which appears below. Lowland raised bogs are peatland ecosystems which develop primarily, but not exclusively, in lowland areas such as the head of estuaries, along river flood-plains and in topographic depressions. In such locations drainage may be impeded by a high groundwater table, or by low permeability substrata such as estuarine, glacial or lacustrine clays. The resultant waterlogging provides anaerobic conditions which slow down the decomposition of plant material which in turn leads to an accumulation of peat. Continued accrual of peat elevates the bog surface above regional groundwater levels to form a gently-curving dome from which the term ‘raised’ bog is derived. The thickness of the peat mantle varies considerably but can exceed 12m. -

PROVO RIVER DELTA RESTORATION PROJECT Final Environmental Impact Statement Volume I: Chapters 1–5

PROVO RIVER DELTA RESTORATION PROJECT Final Environmental Impact Statement Volume I: Chapters 1–5 April 2015 UTAH RECLAMATION 230 South 500 East, #230, Salt Lake City, UT 84102 COMMISSIONERS Phone: (801) 524-3146 – Fax: (801) 524-3148 Don A. Christiansen MITIGATION Brad T. Barber AND CONSERVATION Dallin W. Jensen COMMISSION Dear Reader, April 2015 Attached is the Final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the Provo River Delta Restoration Project (PRDRP). The proposed project would restore a naturally functioning river- lake interface essential for recruitment of June sucker (Chasmistes liorus), an endangered fish species that exists naturally only in Utah Lake and its tributaries. In addition to fulfilling environmental commitments associated with water development projects in Utah and contributing to recovery of an endangered species, the project is intended to help improve water quality on the lower Provo River and to provide enhancements for public recreation in Utah County. Alternative B has been identified as the preferred alternative because it would minimize the amount of private lands that would need to be acquired for the project while still providing adequate space for a naturally functioning river delta and sufficient habitat enhancement for achieving the need for the project. The agencies preparing the Final EIS are the Utah Reclamation Mitigation and Conservation Commission (Mitigation Commission), the Central Utah Water Conservancy District, and the Central Utah Project Completion Act (CUPCA) Office of the U.S. Department of the Interior, collectively referred to as the Joint Lead Agencies. The Final EIS, Executive Summary and Technical Reports can be viewed or downloaded from the project website www.ProvoRiverDelta.us or by requesting a copy on CD. -

Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries

E3: ECOSYSTEMS, ENERGY FLOW, & EDUCATION Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries Eco-systems, Energy Flow, and Education: Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries CONTENT OUTLINE Big Idea / Objectives / Driving Questions 3 Selby Gardens’ Field Study Opportunities 3 - 4 Background Information: 5 - 7 What is an Estuary? 5 Why are Estuaries Important? 5 Why Protect Estuaries? 6 What are Mangrove Wetlands? 6 Why are Mangrove Wetlands Important? 7 Endangered Mangroves 7 Grade Level Units: 8 - 19 8 - 11 (K-3) “Welcome to the Wetlands” 12 - 15 (4-8) “A Magnificent Mangrove Maze” 16 - 19 (7-12) “Monitoring the Mangroves” Educator Resources & Appendix 20 - 22 2 Eco-systems, Energy Flow, and Education: Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries GRADE LEVEL: K-12 SUBJECT: Science (includes interdisciplinary Common Core connections & extension activities) BIG IDEA/OBJECTIVE: To help students broaden their understanding of the Coastal Wetlands of Southwest Florida (specifically focusing on estuaries and mangroves) and our individual and societal interconnectedness within it. Through completion of these units, students will explore and compare the unique contributions and environmental vulnerability of these precious ecosystems. UNIT TITLES/DRIVING QUESTIONS: (Please note: many of the activities span a range of age levels beyond that specifically listed and can be easily modified to meet the needs of diverse learners. For example, the bibomimicry water filtration activity can be used with learners of all ages. Information on modification for -

Guide for Constructed Wetlands

A Maintenance Guide for Constructed of the Southern WetlandsCoastal Plain Cover The constructed wetland featured on the cover was designed and photographed by Verdant Enterprises. Photographs Photographs in this books were taken by Christa Frangiamore Hayes, unless otherwise noted. Illustrations Illustrations for this publication were taken from the works of early naturalists and illustrators exploring the fauna and flora of the Southeast. Legacy of Abundance We have in our keeping a legacy of abundant, beautiful, and healthy natural communities. Human habitat often closely borders important natural wetland communities, and the way that we use these spaces—whether it’s a back yard or a public park—can reflect, celebrate, and protect nearby natural landscapes. Plant your garden to support this biologically rich region, and let native plant communities and ecologies inspire your landscape. A Maintenance Guide for Constructed of the Southern WetlandsCoastal Plain Thomas Angell Christa F. Hayes Katherine Perry 2015 Acknowledgments Our thanks to the following for their support of this wetland management guide: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (grant award #NA14NOS4190117), Georgia Department of Natural Resources (Coastal Resources and Wildlife Divisions), Coastal WildScapes, City of Midway, and Verdant Enterprises. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge The Nature Conservancy & The Orianne Society for their partnership. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of DNR, OCRM or NOAA. We would also like to thank the following professionals for their thoughtful input and review of this manual: Terrell Chipp Scott Coleman Sonny Emmert Tom Havens Jessica Higgins John Jensen Christi Lambert Eamonn Leonard Jan McKinnon Tara Merrill Jim Renner Dirk Stevenson Theresa Thom Lucy Thomas Jacob Thompson Mayor Clemontine F. -

Interactive Comment on “Lake and Mire Isolation Data Set for the Estimation of Post-Glacial Land Uplift in Fennoscandia” by Jari Pohjola Et Al

Discussions Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss., Earth System https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2019-165-RC2, 2019 Science ESSDD © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Open Access Data Interactive comment Interactive comment on “Lake and mire isolation data set for the estimation of post-glacial land uplift in Fennoscandia” by Jari Pohjola et al. Anonymous Referee #2 Received and published: 19 December 2019 The article ‘Lake and mire isolation dataset for the estimation of post-glacial land uplift in Fennoscandia’ of Pohjola et al. presents a collection of data, drawn from existing, both archaeological and palaeoenvironmental sources. It has been made available on the PANGAEA database. The data covers the complete Holocene and provides information about the ages of the earliest radiocarbon dates from mires and lakes, supposed to be representing their earliest stages after being isolated from the Gulf of Bothnia. Combined with spatial information (location and elevation), this is useful to build or validate and optimise land uplift models for Fennoscandia. Some potential pit- Printer-friendly version falls or deficiencies in the use of this data are pointed out. However, certain parts need some more critical discussion while others need clarification in order not to confuse Discussion paper or misguide readers and potential data users. Most of it concerns radiocarbon dating. C1 Furthermore, the dataset uploaded to PANGAEA could benefit from certain additions, especially for the case that inconsistent results need to be evaluated critically. It would ESSDD also get more interesting for disciplines apart from postglacial uplift modelling. -

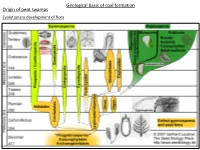

Geological Basis of Coal Formation Origin of Peat Swamps Evolutionary Development of Flora

Geological basis of coal formation Origin of peat swamps Evolutionary development of flora Peat swamp forests are tropical moist forests where waterlogged soil prevents dead leaves and wood from fully decomposing. Over time, this creates a thick layer of acidic peat. Large areas of these forests are being logged at high rates. True coal-seam formation took place only after Middle and Upper Devonian, when the plants spread over continent very rapidly. Devonian coal seams don’t have any economic value. The Devonian period was a time of great tectonic activity, as Euramerica and Gondwana drew closer together. The continent Euramerica (or Laurassia) was created in the early Devonian by the collision of Laurentia and Baltica, which rotated into the natural dry zone along the Tropic of Capricorn, which is formed as much in Paleozoic times as nowadays by the convergence of two great air-masses, the Hadley cell and the Ferrel cell. In these near- deserts, the Old Red Sandstone sedimentary beds formed, made red by the oxidized iron (hematite) characteristic of drought conditions. Sea levels were high worldwide, and much of the land lay under shallow seas, where tropical reef organisms lived. The deep, enormous Panthalassa (the "universal Devonian Paleogeography ocean") covered the rest of the planet. Other minor oceans were Paleo-Tethys, Proto- Tethys, Rheic Ocean, and Ural Ocean (which was closed during the collision with Siberia and Baltica). Carboniferous flora Upper Carboniferous is known as bituminous coal period. 30 m 7 m Permian coal deposits formed predominantly from Gymnosperm Cordaites. Cretaceous and Tertiary peats were formed from angiosperm floras. -

Glossary of Landscape and Vegetation Ecology for Alaska

U. S. Department of the Interior BLM-Alaska Technical Report to Bureau of Land Management BLM/AK/TR-84/1 O December' 1984 reprinted October.·2001 Alaska State Office 222 West 7th Avenue, #13 Anchorage, Alaska 99513 Glossary of Landscape and Vegetation Ecology for Alaska Herman W. Gabriel and Stephen S. Talbot The Authors HERMAN w. GABRIEL is an ecologist with the USDI Bureau of Land Management, Alaska State Office in Anchorage, Alaskao He holds a B.S. degree from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and a Ph.D from the University of Montanao From 1956 to 1961 he was a forest inventory specialist with the USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Regiono In 1966-67 he served as an inventory expert with UN-FAO in Ecuador. Dra Gabriel moved to Alaska in 1971 where his interest in the description and classification of vegetation has continued. STEPHEN Sa TALBOT was, when work began on this glossary, an ecologist with the USDI Bureau of Land Management, Alaska State Office. He holds a B.A. degree from Bates College, an M.Ao from the University of Massachusetts, and a Ph.D from the University of Alberta. His experience with northern vegetation includes three years as a research scientist with the Canadian Forestry Service in the Northwest Territories before moving to Alaska in 1978 as a botanist with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. or. Talbot is now a general biologist with the USDI Fish and Wildlife Service, Refuge Division, Anchorage, where he is conducting baseline studies of the vegetation of national wildlife refuges. ' . Glossary of Landscape and Vegetation Ecology for Alaska Herman W. -

Strangmoor Bog the Unique Formation of Seney’S Natural National Landmark

Strangmoor Bog The Unique Formation of Seney’s Natural National Landmark Photo of a Strangmoor Bog, or String Bog, Seney NWR Schoolcraft County. Photo Courtesy of Josh Cohn—MNFI Seney National Wildlife Refuge, Schoolcraft County - Landmarks are a way to mark our path – easily recognizable, they prevent us from getting lost. From signs on a well-worn trail to the corner store in your neighborhood, landmarks can point us in the right direction. Landmarks are also how we mark our cultural identity and celebrate our past. We can erect a stature to honor a famous person’s work or build a monument to remind us of an important event. Landmarks - based on location or time - help us find our way. The National Natural Landmark Program “The patterned peat bog Natural landmarks are just as crucial and important for marking our within the National Natural paths and history, but instead of humans building a statue or monument to commemorate something, nature has already built Landmark at Seney marks the them. Through the National Natural Landmarks Program, the southern limit of patterned federal government recognizes and cares for natural landmarks, sites that contain rare geological features or plant and animal life. bogs in North America and is the largest and most striking The Secretary of the Interior designates these natural landmarks based on a number of traits: diversity, character, value to science example in Michigan and the and education, condition and rarity. Once designated, the National Lower 48 states..” Park Service administers the program, collaborating with landowners and other partners to conserve the nation’s natural heritage.