The Man Who Would Be King

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

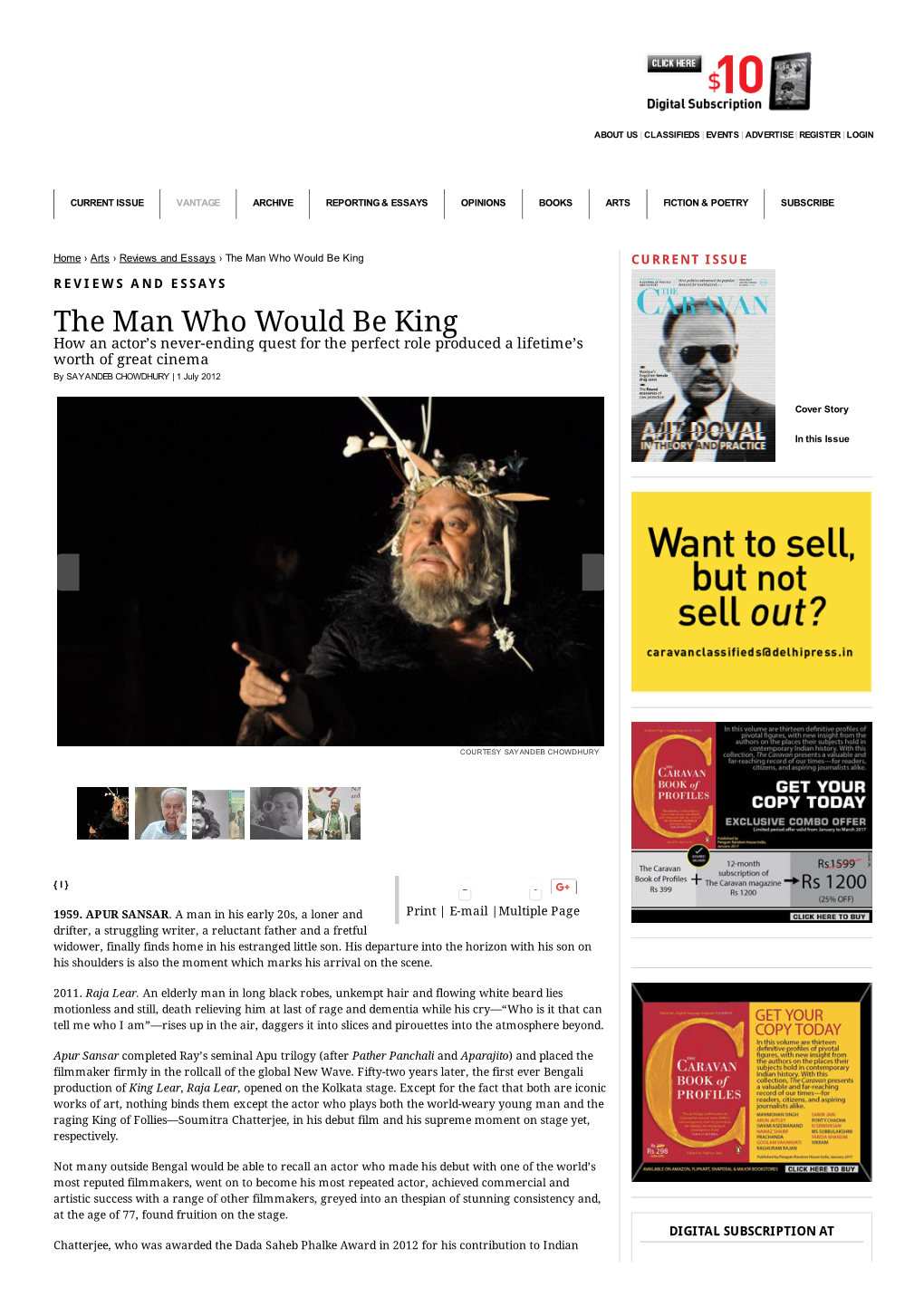

Page 1 of 5 Soumitra Chatterjee's B'day Chat 1/27/2012

Soumitra Chatterjee’s B’day Chat Page 1 of 5 Follow Us: Today's Edition | Thursday , January 19 , 2012 | Search IN TODAY'S PAPER Front Page > Entertainment > Story Front Page Nation Like 12 0 Calcutta Bengal Soumitra Chatterjee’s B’day Chat Opinion Soumitra Chatterjee, who turns 77 today, opens up to filmmaker s-Suman Ghosh on his work, his life International and his dreams. Only for t2. Business Sports Suman Ghosh: Kaku, how old are you going to turn Entertainment on January 19? Sudoku Sudoku New BETA Soumitra Chatterjee: Oh, that I don’t know! But I know Crossword my birth year… 1935. Jumble Gallery So, how do you approach ageing? Horse Racing Press Releases Frankly, the feeling of having to depend on someone Travel else is a bit difficult to deal with. I’m scared of WEEKLY FEATURES dependency. I have never really been dependent on Knowhow someone till now. Jobs Telekids Looking back, would you consider yourself ‘happy’? Personal TT 7days It’s difficult to say that. Happiness in life is occasional… Graphiti temporary. It is like an oasis, if it wasn’t present then life would be like walking in a desert. But talking about work, CITIES AND REGIONS sometimes I wonder how much I can actually give to the Metro society through the work I do…. Just a moment of North Bengal happiness. Northeast Jharkhand I have noticed a change in your attitude towards life Bihar in the last two years. Your usual vivacious self is absent. Why has that happened? Odisha ARCHIVES I would call that melancholia, because I am worried Since 1st March, 1999 about how long I can continue working. -

The Lost Ethos of Uttam-Suchitra Films: a ‘Nostalgic’ Review of Some Classic Romances from the Golden Era of Bengali Cinema Pramila Panda

The lost ethos of Uttam-Suchitra films: a ‘nostalgic’ review of some classic romances from the Golden Era of Bengali cinema Pramila Panda Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 194–200 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk | ISSN 2050-487X | pg. 194 Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 194-200 The lost ethos of Uttam-Suchitra films A ‘nostalgic’ review of some classic romances from the Golden Era of Bengali cinema Pramila Panda [email protected] www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk | ISSN 2050-487X | pg. 195 The mild tune of the sweet and soft song been able to touch every aspect of modern wrapped in sentimental love, “Ogo tumi je human society. This brings us to discussing the aamaar... Ogo tumi je aamaar” (You are status of romance or love in Bengali cinema mine, only mine…) from the Bengali movie half a century back. Harano Sur (Lost Melody) released in 1957 These divine qualities teach us the hymn of still buzzes pleasantries, not only inside my humanity and the art of living. These heavenly ear, but also at the centre of my mind. qualities are highly essential for the survival of Suchitra Sen and Uttam Kumar were the human society in peace and happiness. Of considered the ‘golden couple’ of Bengali films course, the world of cinema has not totally from 1953 to 1978. They left their special ignored the importance of these human identities by contributing the best of qualities to be reflected and utilized through themselves through their marvellous acting the different roles of different characters in talent. -

POWERFUL and POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS in SATYAJIT RAY's FILMS by DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Fi

POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS BY DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts ____________________ Chairperson Committee members* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* Date defended: ______________ The Thesis Committee of Deb Banerjee certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS Committee: ________________________________ Chairperson* _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Date approved:_______________________ ii CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….... 2 Chapter 1: Political Scenario of India and Bengal at the Time Periods of the Two Films’ Production……………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 2: Power of the Ruler/King……………………………………………….. 23 Chapter 3: Power of Class/Caste/Religion………………………………………… 31 Chapter 4: Power of Gender……………………………………………………….. 38 Chapter 5: Power of Knowledge and Technology…………………………………. 45 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………. 52 Work Cited………………………………………………………………………... 55 i Abstract Scholars have discussed Indian film director, Satyajit Ray’s films in a myriad of ways. However, there is paucity of literature that examines Ray’s two films, Goopy -

Sync Sound and Indian Cinema | Upperstall.Com 29/02/12 2:30 PM

Sync Sound and Indian Cinema | Upperstall.Com 29/02/12 2:30 PM Open Feedback Dialog About : Wallpapers Newsletter Sign Up 8226 films, 13750 profiles, and counting FOLLOW US ON RECENT Sync Sound and Indian Cinema Tere Naal Love Ho Gaya The lead pair of the film, in their real life, went in the The recent success of the film Lagaan has brought the question of Sync Sound to the fore. Sync Sound or Synchronous opposite direction as Sound, as the name suggests, is a highly precise and skilled recording technique in which the artist's original dialogues compared to the pair of the are used and eliminates the tedious process of 'dubbing' over these dialogues at the Post-Production Stage. The very first film this f... Indian talkie Alam Ara (1931) saw the very first use of Sync Feature Jodi Breakers Sound film in India. Since then Indian films were regularly shot I'd be willing to bet Sajid Khan's modest personality and in Sync Sound till the 60's with the silent Mitchell Camera, until cinematic sense on the fact the arrival of the Arri 2C, a noisy but more practical camera that the makers of this 'new particularly for outdoor shoots. The 1960s were the age of age B... Colour, Kashmir, Bouffants, Shammi Kapoor and Sadhana Ekk Deewana Tha and most films were shot outdoors against the scenic beauty As I write this, I learn that there are TWO versions of this of Kashmir and other Hill Stations. It made sense to shoot with film releasing on Friday. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Satyajit's Bhooter Raja

postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed ISSN: 2456-7507 postscriptum.co.in Volume II Number i (January 2017) Nag, Sourav K. “Decolonising the Eerie: ...” pp. 41-50 Decolonising the Eerie: Satyajit’s Bhooter Raja (the King of Ghosts) in Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) Sourav Kumar Nag Assistant Professor in English, Onda Thana Mahavidyalaya, Bankura The author is an assistant professor of English at Onda Thana Mahavidyalaya. He has published research articles in various national and international journals. His preferred literary areas include African literature, Literary Theory and Indian English Literature. At present, he is working on his PhD on Ngugi Wa Thiong’o. Abstract This paper is a critical investigation of the socio-political situation of the Indianised spectral king (Bhooter Raja) in Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) and also of Ray’s handling of the marginalised in the movie. The movie is read as an allegory of postcolonial struggle told from a regional perspective. Ray’s portrayal of the Bhooter Raja (The king of ghosts) is typically Indianised. He deliberately deviates from the colonial tradition of Gothic fiction and customised Upendrakishore’s tale as a postcolonial narrative. This paper focuses on Ray’s vision of regional postcolonialism. Keywords ghost, eerie, postcolonial, decolonisation, subaltern Nag, S. K. Decolonising the Eerie ... 42 I cannot help being nostalgic sitting on my desk to write on Satyajit Ray‟s adaptation of Goopy Gayne Bagha Bayne (1969). I remember how I gaped to watch the movie the first time on Doordarsan. Not being acquainted with Bhooter Raja (The king of ghosts) before, I got startled to see the shiny black shadow with flashing electric bulbs around and hearing his reverberated nasal chant of three blessings. -

Lions Film Awards 01/01/1993 at Gd Birla Sabhagarh

1ST YEAR - LIONS FILM AWARDS 01/01/1993 AT G. D. BIRLA SABHAGARH LIST OF AWARDEES FILM BEST ACTOR TAPAS PAUL for RUPBAN BEST ACTRESS DEBASREE ROY for PREM BEST RISING ACTOR ABHISEKH CHATTERJEE for PURUSOTAM BEST RISING ACTRESS CHUMKI CHOUDHARY for ABHAGINI BEST FILM INDRAJIT BEST DIRECTOR BABLU SAMADDAR for ABHAGINI BEST UPCOMING DIRECTOR PRASENJIT for PURUSOTAM BEST MUSIC DIRECTOR MRINAL BANERJEE for CHETNA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER USHA UTHUP BEST PLAYBACK SINGER AMIT KUMAR BEST FILM NEWSPAPER CINE ADVANCE BEST P.R.O. NITA SARKAR for BAHADUR BEST PUBLICATION SUCHITRA FILM DIRECTORY SPECIAL AWARD FOR BEST FILM PREM TELEVISION BEST SERIAL NAGAR PARAY RUP NAGAR BEST DIRECTOR RAJA SEN for SUBARNALATA BEST ACTOR BHASKAR BANERJEE for STEPPING OUT BEST ACTRESS RUPA GANGULI for MUKTA BANDHA BEST NEWS READER RITA KAYRAL STAGE BEST ACTOR SOUMITRA CHATTERHEE for GHATAK BIDAI BEST ACTRESS APARNA SEN for BHALO KHARAB MAYE BEST DIRECTOR USHA GANGULI for COURT MARSHALL BEST DRAMA BECHARE JIJA JI BEST DANCER MAMATA SHANKER 2ND YEAR - LIONS FILM AWARDS 24/12/1993 AT G. D. BIRLA SABHAGARH LIST OF AWARDEES FILM BEST ACTOR CHIRANJEET for GHAR SANSAR BEST ACTRESS INDRANI HALDER for TAPASHYA BEST RISING ACTOR SANKAR CHAKRABORTY for ANUBHAV BEST RISING ACTRESS SOMA SREE for SONAM RAJA BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS RITUPARNA SENGUPTA for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST FILM AGANTUK OF SATYAJIT ROY BEST DIRECTOR PRABHAT ROY for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST MUSIC DIRECTOR BABUL BOSE for MON MANE NA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER INDRANI SEN for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER SAIKAT MITRA for MISTI MADHUR BEST CINEMA NEWSPAPER SCREEN BEST FILM CRITIC CHANDI MUKHERJEE for AAJKAAL BEST P.R.O. -

Unpaid Dividend-16-17-I2 (PDF)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L72200KA1999PLC025564 Prefill Company/Bank Name MINDTREE LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 17-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 737532.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 49/2 4TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANAND NA KORAMANGALA BANGALORE INDIA Karnataka 560095 72.00 24-Feb-2024 2539 unpaid dividend KARNATAKA 69 I FLOOR SANJEEVAPPA LAYOUT MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANTONY FELIX NA MEG COLONY JAIBHARATH NAGAR INDIA Karnataka 560033 72.00 24-Feb-2024 2646 unpaid dividend BANGALORE PLOT NO 10 AIYSSA GARDEN IN301637-41195970- Amount for unclaimed and A BALAN NA LAKSHMINAGAR MAELAMAIYUR INDIA Tamil Nadu 603002 400.00 24-Feb-2024 0000 unpaid dividend -

Beyond the World of Apu: the Films of Satyajit Ray'

H-Asia Sengupta on Hood, 'Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray' Review published on Tuesday, March 24, 2009 John W. Hood. Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2008. xi + 476 pp. $36.95 (paper), ISBN 978-81-250-3510-7. Reviewed by Sakti Sengupta (Asian-American Film Theater) Published on H-Asia (March, 2009) Commissioned by Sumit Guha Indian Neo-realist cinema Satyajit Ray, one of the three Indian cultural icons besides the great sitar player Pandit Ravishankar and the Nobel laureate Rabindra Nath Tagore, is the father of the neorealist movement in Indian cinema. Much has already been written about him and his films. In the West, he is perhaps better known than the literary genius Tagore. The University of California at Santa Cruz and the American Film Institute have published (available on their Web sites) a list of books about him. Popular ones include Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray (1971) by Marie Seton and Satyajit Ray, the Inner Eye (1989) by Andrew Robinson. A majority of such writings (with the exception of the one by Chidananda Dasgupta who was not only a film critic but also an occasional filmmaker) are characterized by unequivocal adulation without much critical exploration of his oeuvre and have been written by journalists or scholars of literature or film. What is missing from this long list is a true appreciation of his works with great insights into cinematic questions like we find in Francois Truffaut's homage to Alfred Hitchcock (both cinematic giants) or in Andre Bazin's and Truffaut's bio-critical homage to Orson Welles. -

Speaking Through Troubled Times

Speaking through Troubled Times Moinak Biswas I would like to talk about the encounter between cinema and a moment in our political history in this essay. Is it possible to identify the voices that cinema sifts out of a time, and make them narrate to us a story that was there in the films but not told? I would like to ask that question about the cusp of the nineteen sixties and seventies. 1. There now exists a sizeable literature on the relationship between history and cinema. Academic historians have looked at the relationship mainly in terms of representation of the past. The fragile status that facts attain in a popular medium was the starting point of historians’ serious engagement with film, the more sophisticated version of which took up the issue of concretization of the past on screen, the process of giving body to a time that is gone, and the necessary ambivalence that it brings on. The other focus of the discussion has been narrative of course, the relationship of the events in history as they appear on screen. Since the larger historians’ debate had narrative as the cardinal point of contention - narrativity as a category came to problematize the entire question of truth-telling in historiography in the wake of semiotic criticism - the filmic imperatives of sequencing of events from the past has been another cause of concern. Professional historians such as Natalie Davis and Robert Rosenstone have written on these questions quite extensively [1], as have Daniel Walkowitz, R. C. Raack and Robert Brent Toplin, all of whom have developed strong ties with film and television production, as advisors and screenwriters [2]. -

The 59TH National Film Awards Function by : INVC Team Published on : 2 May, 2012 09:45 PM IST

The 59TH National Film Awards function By : INVC Team Published On : 2 May, 2012 09:45 PM IST [caption id="attachment_41188" align="alignleft" width="300" caption="The Dadasaheb Phalke Awardee, Shri Soumitra Chatterjee, film Producer, Shri Jaaved Jaaferi and Ashvin Kumar, the Producer, Director, Shri Sankalp Meshram, the film Director, Shri Satish Pande and the Director, Directorate of Film Festival, Shri Rajeev Kumar Jain at a Press Conference on the occasion of 59th National Film Awards Ceremony, organized by the DFF, in New Delhi."] [/caption] INVC,, Delhi,, The 59TH National Film Awards function will be held tomorrow at Vigyan Bhawan. The awards will be given away by the Hon’ble Vice President of India. Minister of Information & Broadcasting, Smt. Ambika Soni will also be present on the occasion. The highlights of the 59th National Film Awards are as follows: The top honour in the Feature Film category, the Best Film is shared by films Deool (Marathi) produced by Abhijeet Gholap & directed by Umesh Vinayak Kulkarni and Byari (Byari language) produced by T.H. Althaf Hussain & directed by Suveeram. The award carries Swarna Kamal and cash prize of Rs. 2,50,000/-. In Non- feature film category the top honour , Best Film goes to And We Play On (Hindi & English)directed and produced by Pramod Purswane . The awards carries Swarna Kamal and Cash prize of Rs. 1,50,000/-. In Best Writing on Cinema category the Swarna Kamal goes to the book titled R.D. Burman – The Man, The Music written by Anirudha Bhattacharjee & Balaji Vittal, published by Harper Collins India.