Shelter Meeting 08A Breakout Group Minutes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Burma

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO BURMA RANGOON CITY AREA AFFECTED AREAS Affected Townships (as reported by the Government of Burma) American Red Cross aI SOURCE: MIMU ASEAN B Implementing NGO aD BAGO DIVISION IOM B Kyangin OCHA B (WEST) UNHCR I UNICEF DG JF Myanaung WFP E Seikgyikanaunglo WHO D UNICEF a WFP Ingapu DOD E RAKHINE b AYEYARWADY Dala STATE DIVISION UNICEF a Henzada WC AC INFORMA Lemyethna IC TI Hinthada PH O A N Rangoon R U G N O I T E G AYEYARWADY DIVISION ACF a U Zalun S A Taikkyi A D ID F MENTOR CARE a /DCHA/O D SC a Bago Yegyi Kyonpyaw Danubyu Hlegu Pathein Thabaung Maubin Twantay SC RANGOON a CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE AC Hmawbi See Inset WC AC Htantabin Kyaunggon DIVISION Myaungmya Kyaiklat Nyaungdon Kayan Pathein Einme Rangoon SC/US JCa CWS/IDE AC Mayangone ! Pathein WC AC Î (Yangon) Thongwa Thanlyin Mawlamyinegyun Maubin Kyauktan Kangyidaunt Twantay CWS/IDE AC Myaungmya Wakema CWS/IDE Kyauktan AC PACT CIJ Myaungmya Kawhmu SC a Ngapudaw Kyaiklat Mawlamyinegyun Kungyangon UNDP/PACT C Kungyangon Mawlamyinegyun UNICEF Bogale Pyapon CARE a a Kawhmu Dedaye CWS/IDE AC Set San Pyapon Ngapudaw Labutta CWS/IDE AC UNICEF a CARE a IRC JEDa UNICEF a WC Set San AC SC a Ngapudaw Labutta Bogale KEY SC/US JCa USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP DOD Pyinkhayine Island Bogale A Agriculture and Food Security SC JC a Air Transport ACTED AC b Coordination and Information Management Labutta ACF a Pyapon B Economy and Market Systems CARE C !Thimphu ACTED a CARE Î AC a Emergency Food Assistance ADRA CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE aIJ AC Emergency Relief Supplies Dhaka IOM a Î! CWS/IDE AC a UNICEF a D Health BURMA MERLIN PACT CJI DJ E Logistics PACT ICJ SC a Dedaye Vientiane F Nutrition Î! UNDP/PACT Rangoon SC C ! a Î ACTED AC G Protection UNDP/PACT C UNICEF a Bangkok CARE a IShelter and Settlements Î! UNICEF a WC AC J Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene WC WV GCJI AC 12/19/08 The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. -

UNDP Myanmar Responds to Cyclone Nargis

UNDP Myanmar responds MATTERS OF FACT to Cyclone Nargis • 40 UNDP and its implementing partner NGO PACT offices in the Ayeyarwady Delta UNDP moved into action within 24 hours after Cyclone • 23 field teams active in the worst affected areas Nargis hit Myanmar on 2-3 May. The storm carved a • 500 national staff and project personnel working in the path of destruction that left 133,653 dead or missing delta and being mobilized for Cyclone Nargis response and 2.4 million severely affected by the crisis. operations • 5 UNDP offices functioning as ‘base camp’ for UN The cyclone’s 120-mile per hour winds and resulting organizations and international NGOs delivering to, and storm surge were particularly devastating in the working in Bogale, Mawlamyinegyun, Labutta, Ayeyarwady Delta, where entire villages were flattened. Ngapudaw and Kyaiklat • 2.4 million people severely affected by Cyclone UNDP is the only UN organization with field offices Nargis across Myanmar located in the region, which, prior to the cyclone was • 1.4 million people affected in the Ayeyarwady delta, home to seven million people. UNDP staff and families the hardest hit region of Myanmar experienced the natural disaster first-hand, as did those • 43,241 estimated total beneficiaries from UNDP coordinated relief efforts as of 21 May who work for partner non-governmental organization (NGO) PACT, which lost five of its project personnel. Supporting relief efforts: UNDP sent rotating teams UNDP has 40 functioning field offices in the delta and of national staff to work with and relieve its field staff in current field staff strength of more than 500 five of the affected townships – Bogale, experienced national staff and project personnel, Mawlamyinegyun, Labutta, Ngapudaw and Kyaiklat – including those of PACT. -

Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine - Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine

Urban Development Plan Development Urban The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Construction for Regional Cities The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Urban Development Plan for Regional Cities - Mawlamyine and Pathein Mandalay, - Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine - - - REPORT FINAL Data Collection Survey on Urban Development Planning for Regional Cities FINAL REPORT <SUMMARY> August 2016 SUMMARY JICA Study Team: Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. Nine Steps Corporation International Development Center of Japan Inc. 2016 August JICA 1R JR 16-048 Location業務対象地域 Map Pannandin 凡例Legend / Legend � Nawngmun 州都The Capital / Regional City Capitalof Region/State Puta-O Pansaung Machanbaw � その他都市Other City and / O therTown Town Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Don Hee 道路Road / Road � Shin Bway Yang � 海岸線Coast Line / Coast Line Sumprabum Tanai Lahe タウンシップ境Township Bou nd/ Townshipary Boundary Tsawlaw Hkamti ディストリクト境District Boundary / District Boundary INDIA Htan Par Kway � Kachinhin Chipwi Injangyang 管区境Region/S / Statetate/Regi Boundaryon Boundary Hpakan Pang War Kamaing � 国境International / International Boundary Boundary Lay Shi � Myitkyina Sadung Kan Paik Ti � � Mogaung WaingmawミッチMyitkyina� ーナ Mo Paing Lut � Hopin � Homalin Mohnyin Sinbo � Shwe Pyi Aye � Dawthponeyan � CHINA Myothit � Myo Hla Banmauk � BANGLADESH Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Katha Momauk Lwegel � Pinlebu Monekoe Maw Hteik Mansi � � Muse�Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Cikha Wuntho �Manhlyoe (Manhero) � Namhkan Konkyan Kawlin Khampat Tigyaing � Laukkaing Mawlaik Tonzang Tarmoenye Takaung � Mabein -

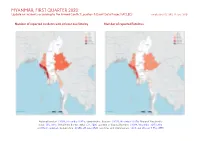

MYANMAR, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 29 June 2020

MYANMAR, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 29 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Bhutan/China border status: CIA, 2012; China/India border status: CIA, 2006; geodata of disputed borders: GADM, November 2015a; Nat- ural Earth, undated; incident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 MYANMAR, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 29 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Battles 199 33 175 Conflict incidents by category 2 Explosions / Remote 154 34 64 Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 2 violence Protests 101 0 0 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 75 23 37 Conflict incidents per province 4 Strategic developments 49 0 0 Riots 6 2 2 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 584 92 278 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 MYANMAR, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 29 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. -

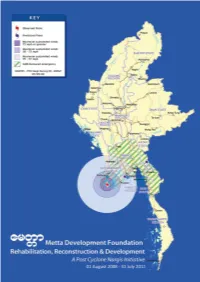

Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development a Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative

Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative 1 2 Metta Development Foundation Table of Contents Forward, Executive Director 2 A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative - Executive Summary 6 01. Introduction – Waves of Change The Ayeyarwady Delta 10 Metta’s Presence in the Delta. The Tsunami 11 02. Cyclone Nargis –The Disaster 12 03. The Emergency Response – Metta on Site 14 04. The Global Proposal 16 The Proposal 16 Connecting Partners - Metta as Hub 17 05. Rehabilitation, Reconstruction and Development August 2008-July 2011 18 Introduction 18 A01 – Relief, Recovery and Capacity Building: Rice and Roofs 18 A02 – Food Security: Sowing and Reaping 26 A03 – Education: For Better Tomorrows 34 A04 – Health: Surviving and Thriving 40 A05 – Disaster Preparedness and Mitigation: Providing and Protecting 44 A06 – Lifeline Systems and Transportation: The Road to Safety 46 Conclusion 06. Local Partners – The Communities in the Delta: Metta Meeting Needs 50 07. International Partners – The Donor Community Meeting Metta: Metta Day 51 08. Reporting and External Evaluation 52 09. Cyclones and Earthquakes – Metta put anew to the Test 55 10. Financial Review 56 11. Beyond Nargis, Beyond the Delta 59 12. Thanks 60 List of Abbreviations and Acronyms 61 Staff Directory 62 Volunteers 65 Annex 1 - The Emergency Response – Metta on Site 68 Annex 2 – Maps 76 Annex 3 – Tables 88 Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative 3 Forword Dear Friends, Colleagues and Partners On the night of 2 May 2008, Cyclone Nargis struck the delta of the Ayeyarwady River, Myanmar’s most densely populated region. The cyclone was at the height of its destructive potential and battered not only the southernmost townships but also the cities of Yangon and Bago before it finally diminished while approaching the mountainous border with Thailand. -

Cyclone Nargis

Emergency appeal n° MDRMM002 Myanmar: GLIDE n° TC-2008-000057-MMR Operations update n° 11 23 May 2008 Cyclone Nargis Period covered by this Update: one week since revised emergency appeal launched Revised Emergency Appeal launched 16 May 2008: CHF 52,857,809 (USD 50.8 million or EUR 32.7 million) to assist 100,000 families for three years; <click here to view the attached Emergency Appeal Budget> The revised plan of action covers the provision of life- saving assistance and short-term relief (for up to six months) as well as medium and longer term recovery needs. It aims to support a significant scaling up in the Building trust: MRCS volunteers let humanitarian response of Myanmar Red Cross Society families speak for themselves in terms of (MRCS) as well as the wider Red Cross Red Crescent what they need. Movement. The appeal seeks to do this in a way that: is sensitive to the national society’s capacity; builds on MRCS’s long term strengths; and takes account of the operational challenges that exist. In light of all this, partners are requested to continue their excellent support and understanding to the Cyclone Nargis appeal. <Click here to link to the donor response list> <click here to link to contact details > Appeal history: • 16 May 2008: A revised emergency appeal launched for CHF 52,857,809 (USD 50.8 million or EUR 32.7 million) to assist 100,000 families for three years • 6 May 2008: A preliminary emergency appeal launched for CHF 6,290,909 (USD 5.9 million or EUR 3.86 million) for six months to assist 30,000 families. -

Enhancing Resilience and Reducing the Risk of Disasters in the Ayeyarwady Region, Myanmar

Learning for impact Disaster Risk Reduction photo: SEEDS Asia ENHANCING RESILIENCE AND REDUCING THE RISK OF DISASTERS IN THE AYEYARWADY REGION, MYANMAR In 2013, Y Care International supported the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) of Myanmar to carry out a pilot project focusing on disaster risk reduction (DRR) in the Townships of Einme and Ngapudaw in the Ayeyarwady Region of Myanmar. The project aimed to build resilience and reduce vulnerability of communities exposed to natural hazards such as floods, cyclones, earthquakes and landslides. CWS-Asia/Pacific provided support to the YMCA in-country and liaised closely with Y Care International throughout. The project focused on strengthening the capacity of the YMCA Head Office, the local YMCA branch in Pathein and communities on disaster preparedness, mitigation and response; on fostering a culture of learning and learning opportunities around youth led DRR. The pilot project was evaluated in January 2014 and key findings and recommendations are summarised below. KEY FINDINGS Innovative training necessary action in any context, it requires them to A Mobile Knowledge Resource Centre (MKRC) led by have a certain level of knowledge, interest, and desire SEEDS Asia was used to provide training for young to take action. The materials of the MKRC are viewed volunteers through a mobile truck which contained as highly innovative, interactive, fun and interesting, interactive models and other learning aids. The and suitable for people will low levels of literacy or approach is based on the idea that for people to take mobility. The materials were very well received by 2 KEY FINDINGS (CONTINUED) Myanmar it was much easier to carry out activities at the community level compared to those that are not the project communities and have been successful registered. -

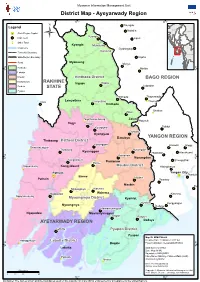

Ayeyarwady Region

Myanmar Information Management Unit District Map - Ayeyarwady Region 95° E 96° E Paungde Legend INDIA Nattalin CHINA .! State/Region Capital Kyangin Main Town Ü Zigon !( Other Town Kyangin Myanaung Coast Line !( Gyobingauk Kanaung Township Boundary THAILAND State/Region Boundary Okpho Road Myanaung Monyo N Kyeintali N ° Hinthada !( ° 8 Minhla 8 1 1 Labutta Maubin Hinthada District BAGO REGION Myaungmya RAKHINE Ingapu Ingapu Pathein STATE Letpadan Pyapon Hinthada Thayarwady Gwa Lemyethna Lemyethna !( Thonse Hinthada Okekan Zalun !( Ngathaingchaung Zalun !( Ahpyauk !( Yegyi Yegyi Kyonpyaw Taikkyi Danubyu Kyonpyaw Danubyu YANGON REGION Thabaung Pathein District Kyaunggon Hmawbi Hlegu Shwethaungyan !( Thabaung Nyaungdon Kyaunggon Htantabin Htaukkyant N N ° Pantanaw ° 7 7 1 Nyaungdon 1 Kangyidaunt Pantanaw Shwepyithar Einme Ngwesaung Kangyidaunt Maubin District !( Hlaingtharya Pathein Yangon City .! .! Thanlyin Einme Maubin Pathein Twantay Maubin Kyauktan Myaungmya Wakema Ngapudaw Wakema Kawhmu Ngayokekaung !( Myaungmya District Kyaiklat Kyaiklat Kungyangon Myaungmya Dedaye Mawlamyinegyun Ngapudaw Mawlamyinegyun Bogale Pyapon AYEYARWADY REGION Dedaye Labutta Pyapon District Pyapon Map ID: MIMU764v04 Hainggyikyun Creation Date: 23 October 2017.A4 N Labutta District N !( ° Bogale Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 ° 6 6 1 1 Labutta Data Sources: MIMU Base Map: MIMU Boundaries: MIMU/WFP Pyinsalu Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) !( Ahmar translated by MIMU !( Email: [email protected] Website: www.themimu.info Kilometers Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit 2017. May be used free of charge with attribution. 0 10 20 40 95° E 96° E Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

Mimu939v01 29Nov12 SDC S

Myanmar Information Management Unit SDC-HA School/Storm Shelter Project Bogale, Labutta, Mawlamyinegyun and Pyapon Townships, Ayeyarwady Region 94°30'E 94°40'E 94°50'E Myaungmya 95°E 95°10'E Wakema 95°20'E 95°30'E 95°40'E 95°50'E Twantay Einme Maubin BHUTAN INDIA Kachin CHINA Ngapudaw Ü Sagaing Chin Shan Mandalay Magway LAOS Kyaiklat Kayah Rakhine Bago 16°30'N Myaungmya 16°30'N Yangon Kawhmu Wakema Ayeyarwady Kayin THAILAND Mon Ngapudaw Tanintharyi Kyaiklat Tone Hle Ywa Ma (Myo Ma Ward (8)) ! Mawlamyinegyun Bar Thar Kone (Bar Thar Kone) ! ! Ywar Thit Mawlamyinegyun (Min Bu Su) 16°20'N Thar Li Kar Kone Hta Nyet Chaung Hpa Yar Gyi Kone/Hpa Yar Kone 16°20'N (Thar Li Kar Kone) (Me Za Li U To) (Bant Bway Su) ! ! ! Dedaye Bogale Hpoe Shwe Lone (Haing Si) ! Pyapon Myat Thar Ywar Ma Yae Hpyu Kan (Myat Thar Ywar Ma) (Ka Ka Yan) ! ! Thaung Hpone Bay Pauk (Shauk Chaung) Da Ni Chaung (Shaw Chaung) ! (Kyet Shar) ! ! Yae Ka Myin (Ah Lel Yae Kyaw) ! Pyapon 16°10'N 16°10'N Labutta Ah Lan Hpa Lut (Ah Lan Hpa Lut) ! Ka Zaung Ma/ Ka Yaung Ma (Nga Pyay Ma) ! Bogale Ah Htet Hpoe Nyo (Nga Pyay Ma) Let Pan ! (Let Pan Pin) ! Kyon Ka Dun (Kyon Ka Dun) Set San Hnget Ka Lay Kwin East 2 ! (Set San) (Zin Baung) ! ! ! Aung Chan Thar ! (Set San) Hnget Ka Lay Kwin East 1 (Zin Baung) War Chaung (Day Da Lu) ! Tar Pun Thea Chaung Lay Gwa Saing (Day Da Lu ) (Daunt Gyi) (Daunt Gyi) ! Ah Si Gyi ! ! (Set San) Oke Twin 16°N ! (Day Da Lu ) 16°N ! Boe Su Chaung Hpa Yar Gyi Kone (Day Da Lu ) (Myo Kone ) ! ! !Hpo Khway Yoe (Myo Kone ) Shwe Htee (Day Da Lu ) ! Labutta Kan Su (Myo -

Socioeconomic Characteristics of Hilsa Fishers in the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar Opportunities and Challenges

A position Paper Prepared for the New Perspectives on Climate Resilient Drylands Development Project Socioeconomic characteristics of hilsa fishers in the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar Opportunities and challenges Wae Win Khaing, Michael Akester, Eugenia Merayo Garcia, Annabelle Bladon and Essam Yassin Mohammed Country Report Fisheries; Poverty Keywords: December 2018 Sustainable fisheries; ocean; poverty reduction; livelihoods; communities About the authors Wae Win Khaing, Network Activities Group; Michael Akester, WorldFish Myanmar, Eugenia Merayo Garcia, International Institute for Environment and Development; Annabelle Bladon, International Institute for Environment and Development; Essam Yassin Mohammed, International Institute for Environment and Development. Corresponding author email [email protected] Produced by IIED’s Shaping Sustainable Markets group IIED's Shaping Sustainable Markets group works to make sure that local and global markets are fair and can help poor people and nature thrive. Our research focuses on the mechanisms, structures and policies that lead to sustainable and inclusive economies. Our strength is in finding locally appropriate solutions to complex global and national problems. Acknowledgements We would like to thank all participants of the socioeconomic survey that formed the basis of this report – particularly the Ayeyarwady Delta fisherfolk. We thank the Ayeyarwady Region Department of Fisheries, township Department of Fisheries offices, and the Myanmar Fisheries Federation for their support. We also recognise the contributions of WorldFish, the FISH CGIAR Research program, and Bobby Maung and Myo Zaw Aung from the Network Activities Group. Published by IIED, December 2018 Wae Win Khaing, Michael Akester, Eugenia Merayo Garcia, Annabelle Bladon and Essam Yassin Mohammed (editor) (2018) Socioeconomic characteristics of hilsa fishers in the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar: Opportunities and challenges. -

Region Map District Ayeyarwa

Myanm aInform r a tionMa na g e m eUnit nt DistrictMa Ayeyarwad p- Reg y ion 95°E 96°E Map ID: MIMU764v05 Prod uctionAprilDate:24 2020 PapeSize: r A4 Projection/Datum:Geog raphic/WGS84 DataSource: Bas ema MIMU, p:OSM, MPA PlaceNam eGene s : ralAdm inistrationDepa rtme(GAD) nt and field sources . Kyang in Placena m e son thisprod are uct inline withthe ge ne ralcartog raphicpractice to Batye reflectthena m e sofsuch places as de s ignathe tedgovernmby econcerne nt d . Rakhine (! Trans literationMIMU.by Kyang in Myana ung Theinforma tioncontaine don this prod is provide uct d“as is”, for refe rence purpos e sonly, bas e don current available informa tion.The United Nations and State (! Kana ung theMIMU spe cificallydo notma keany warranties or repres e ntationsas theto a ccuracyor com pletene s sof such informa tionnor doe simply it official e nd orse m eor nt acceptance theby United Nations Plea . s esha reupd a teson a nyerrors or om iss ionsviama ps @the m imu.info. (!PinIn Myana ung Thisprod ha uct sbee nprepa redfor ope rationapurpos l e sonly,supportto huma nitarianand de velopm eactivities nt inMyanm a r. Notethisthama t pma notshow y all island sofcoa sarea tal sdue scaleto 18° N 18° (!Htoog yi limitations . N 18° Hinthada © 2020 Myanmar Information Management UnitMIMU prod. are ucts notfor District (! MeZa KoneLi s a leand can beuse dfree ofcha rgewithattribution. Emainfo.mimu@und il: p.orgWe bsite:www.the m imu.info Ing a pu Ing a pu Legend Bago !. State/Reg ionCapital TaLoke Htaw Hintha d a MainTown (! Region Lem yethna Lem yethna (! O theTown r Hintha d a DuYar (! o (! Airport Z a lun Sea port Nga tha ing cha ung Z a lun (! Towns hipBound a ry Yeg yi Yeg yi Ahtaung (! State/Reg ionBound a ry Kyonpyaw Danubyu Danubyu Roa d Kyonpyaw Ahthoke Railway Tha baung Pathein (! District Kyaung g on INDIA Shwetha ung yan CHINA (! Tha baung Nyaung d on BANGLA DESH Kyaung g on Pantana w 17° N 17° Cha ungTha r N 17° (! Nyaung d on LAOS Kang yida unt o Einm e Maubin (! Ngwes a ung Pantana w (! Kang yida unt District o! THAILAND ( ( Einm e Pathe in !. -

Ayeyarwady Region - Myanmar

Myanmar Information Management Unit AYEYARWADY REGION - MYANMAR 94°10'E 95°0'E 95°50'E Paungde Thandwe Thandwe Airport Nattalin Kyangin Zigon Kyangin Myanaung Township Gyobingauk Kanaung RAKHINE Okpho Myanaung BAGO Township Monyo Kyeintali 18°0'N Minhla 18°0'N Ingapu Township Ingapu Letpadan Hinthada Thayarwady Lemyethna Thonse Lemyethna Hinthada Gwa Township Township Okekan Zalun Zalun Township Ngathaingchaung Yegyi Ahpyauk Township Yegyi 17°20'N Kyonpyaw Taikkyi 17°20'N Kyonpyaw Danubyu BAY OF BENGAL Township Danubyu Township Thabaung YANGON Hmawbi Township Airport Kyaunggon Hmawbi Shwethaungyan Nyaungdon Thabaung Kyaunggon Htaukkyant Nyaungdon Township Htantabin Township Pantanaw Pantanaw Shwepyithar Kangyidaunt Township Yangon Airport Einme Ngwesaung Pathein Hlaingtharya Kangyidaunt Township Pathein Airport Township Yangon Pathein Maubin City Einme Township Township Maubin Twantay Wakema 16°40'N Township 16°40'N Myaungmya Wakema Ngapudaw Kawhmu Ngayokekaung Myaungmya Kyaiklat Township Township AYEYARWADY Kyaiklat Kungyangon Dedaye Mawlamyinegyun Ngapudaw Township Mawlamyinegyun Dedaye Township Bogale Pyapon Township Labutta Pyapon Bogale Township Township Hainggyikyun 16°0'N 16°0'N Labutta Township Pyinsalu Ahmar Kilometers 0 5 10 20 30 94°10'E 95°0'E 95°50'E Myanmar Information Management Unit (MIMU) Map ID: MIMU940v02 Data Sources : Capital Township Boundary < 50 750 - 1,000 2,000 - 2,250 3,250 - 3,500 is a common resource of the Humanitarian Airports Base Map - MIMU Creation Date: 3 July 2015.A1 Country Team (HCT) providing information