THE STATE of LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS in AYEYARWADY Photo Credits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yangon University of Economics Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Programme

YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE MASTER OF BANKING AND FINANCE PROGRAMME INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE (CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION) KHET KHET MYAT NWAY (MBF 4th BATCH – 30) DECEMBER 2018 INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION A thesis summited as a partial fulfillment towards the requirements for the Degree of Master of Banking and Finance (MBF) Supervised By : Submitted By: Dr. Daw Tin Tin Htwe Ma Khet Khet Myat Nway Professor MBF (4th Batch) - 30 Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Yangon University of Economics Yangon University of Economics ABSTRACT This study aims to identify the influencing factors on farms’ performance in Bogale Township. This research used both primary and secondary data. The primary data were collected by interviewing with farmers from 5 groups of villages. The sample size includes 150 farmers (6% of the total farmers of each village). Survey was conducted by using structured questionnaires. Descriptive analysis and linear regression methods are used. According to the farmer survey, the household size of the respondent is from 2 to 8 members. Average numbers of farmers are 2 farmers. Duration of farming experience is from 11 to 20 years and their main source of earning is farming. Their living standard is above average level possessing own home, motorcycle and almost they owned farmland and cows. The cultivated acre is 30 acres maximum and 1 acre minimum. Average paddy yield per acre is around about 60 bushels per acre for rainy season and 100 bushels per acre for summer season. -

A Delicate Balance Negotiating Isolation and Globalization in the Burmese Performing Arts Catherine Diamond

A Delicate Balance Negotiating Isolation and Globalization in the Burmese Performing Arts Catherine Diamond If you walk on and on, you get to your destination. If you question much, you get your information. If you do not sleep and idle, you preserve your life! (Maung Htin Aung 1959:87) So go the three lines of wisdom offered to the lazy student Maung Pauk Khaing in the well- known eponymous folk tale. A group of impoverished village youngsters, led by their teacher Daw Khin Thida, adapted the tale in 2007 in their first attempt to perform a play. From a well-to-do family that does not understand her philanthropic impulses, Khin Thida, an English teacher by profession, works at her free school in Insein, a suburb of Yangon (Rangoon) infamous for its prison. The shy students practiced first in Burmese for their village audience, and then in English for some foreign donors who were coming to visit the school. Khin Thida has also bought land in Bagan (Pagan) and is building a culture center there, hoping to attract the street children who currently pander to tourists at the site’s immense network of temples. TDR: The Drama Review 53:1 (T201) Spring 2009. ©2009 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 93 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/dram.2009.53.1.93 by guest on 02 October 2021 I first met Khin Thida in 2005 at NICA (Networking and Initiatives for Culture and the Arts), an independent nonprofit arts center founded in 2003 and run by Singaporean/Malaysian artists Jay Koh and Chu Yuan. -

Media Release Singapore Art Museum Reveals Singapore

Media Release Singapore Art Museum Reveals Singapore Biennale 2016 Artists and Artwork Highlights ‘An Atlas of Mirrors’ Explained Through 9 Curatorial Sub-Themes Singapore, 22 September 2016 – The Singapore Art Museum (SAM) today revealed a list of 62 artists and art collectives and selected artwork highlights of the Singapore Biennale 2016 (SB2016), one of Asia’s most exciting contemporary visual art exhibitions. Titled An Atlas of Mirrors, SB2016 draws on diverse artistic viewpoints that trace the migratory and intertwining relationships within the region, and reflect on shared histories and current realities with East and South Asia. SB2016 will present 60 artworks that respond to An Atlas of Mirrors, including 49 newly commissioned and adapted artworks. The SB2016 artworks, spanning various mediums, will be clustered around nine sub-themes and presented across seven venues – Singapore Art Museum and SAM at 8Q, Asian Civilisations Museum, de Suantio Gallery at SMU, National Museum of Singapore, Stamford Green, and Peranakan Museum. The full artist list can be found in Annex A. SB2016 Artists In addition to the 30 artists already announced, SB2016 will include Chou Shih Hsiung, Debbie Ding, Faizal Hamdan, Abeer Gupta, Subodh Gupta, Gregory Halili, Agan Harahap, Kentaro Hiroki, Htein Lin, Jiao Xingtao, Sanjay Kak, Marine Ky, H.H. Lim, Lim Soo Ngee, Made Djirna, Made Wianta, Perception3, Niranjan Rajah, S. Chandrasekaran, Sharmiza Abu Hassan, Nilima Sheikh, Praneet Soi, Adeela Suleman, Melati Suryodarmo, Nobuaki Takekawa, Jack Tan, Tan Zi Hao, Ryan Villamael, Wen Pulin, Xiao Lu, Zang Honghua, and Zulkifle Mahmod. SB2016 artists are from 18 countries and territories in Southeast Asia, South Asia and East Asia. -

ANNEX 12C: PROFILE of MA SEIN CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE International Institute of Rural Reconstruction; ;

ANNEX 12C: PROFILE OF MA SEIN CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE International Institute of Rural Reconstruction; ; © 2018, INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF RURAL RECONSTRUCTION This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original work is properly credited. Cette œuvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode), qui permet l’utilisation, la distribution et la reproduction sans restriction, pourvu que le mérite de la création originale soit adéquatement reconnu. IDRC Grant/ Subvention du CRDI: 108748-001-Climate and nutrition smart villages as platforms to address food insecurity in Myanmar 33 IDRC \CRDl ..m..»...u...».._. »...m...~ c.-..ma..:«......w-.«-.n. ...«.a.u CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE PROFILE Ma Sein Village Bogale Township, Ayeyarwaddy Region 2 Climate Smart Village Profile Introduction Myanmar is the second largest country in Southeast Asia bordering Bangladesh, Thailand, China, India, and Laos. It has rich natural resources – arable land, forestry, minerals, natural gas, freshwater and marine resources, and is a leading source of gems and jade. A third of the country’s total perimeter of 1,930 km (1,200 mi) is coastline that faces the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. The country’s population is estimated to be at 60 million. Agriculture is important to the economy of Myanmar, accounting for 36% of its economic output (UNDP 2011a), a majority of the country’s employment (ADB 2011b), and 25%–30% of exports by value (WB–WDI 2012). -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Burma

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO BURMA RANGOON CITY AREA AFFECTED AREAS Affected Townships (as reported by the Government of Burma) American Red Cross aI SOURCE: MIMU ASEAN B Implementing NGO aD BAGO DIVISION IOM B Kyangin OCHA B (WEST) UNHCR I UNICEF DG JF Myanaung WFP E Seikgyikanaunglo WHO D UNICEF a WFP Ingapu DOD E RAKHINE b AYEYARWADY Dala STATE DIVISION UNICEF a Henzada WC AC INFORMA Lemyethna IC TI Hinthada PH O A N Rangoon R U G N O I T E G AYEYARWADY DIVISION ACF a U Zalun S A Taikkyi A D ID F MENTOR CARE a /DCHA/O D SC a Bago Yegyi Kyonpyaw Danubyu Hlegu Pathein Thabaung Maubin Twantay SC RANGOON a CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE AC Hmawbi See Inset WC AC Htantabin Kyaunggon DIVISION Myaungmya Kyaiklat Nyaungdon Kayan Pathein Einme Rangoon SC/US JCa CWS/IDE AC Mayangone ! Pathein WC AC Î (Yangon) Thongwa Thanlyin Mawlamyinegyun Maubin Kyauktan Kangyidaunt Twantay CWS/IDE AC Myaungmya Wakema CWS/IDE Kyauktan AC PACT CIJ Myaungmya Kawhmu SC a Ngapudaw Kyaiklat Mawlamyinegyun Kungyangon UNDP/PACT C Kungyangon Mawlamyinegyun UNICEF Bogale Pyapon CARE a a Kawhmu Dedaye CWS/IDE AC Set San Pyapon Ngapudaw Labutta CWS/IDE AC UNICEF a CARE a IRC JEDa UNICEF a WC Set San AC SC a Ngapudaw Labutta Bogale KEY SC/US JCa USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP DOD Pyinkhayine Island Bogale A Agriculture and Food Security SC JC a Air Transport ACTED AC b Coordination and Information Management Labutta ACF a Pyapon B Economy and Market Systems CARE C !Thimphu ACTED a CARE Î AC a Emergency Food Assistance ADRA CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE aIJ AC Emergency Relief Supplies Dhaka IOM a Î! CWS/IDE AC a UNICEF a D Health BURMA MERLIN PACT CJI DJ E Logistics PACT ICJ SC a Dedaye Vientiane F Nutrition Î! UNDP/PACT Rangoon SC C ! a Î ACTED AC G Protection UNDP/PACT C UNICEF a Bangkok CARE a IShelter and Settlements Î! UNICEF a WC AC J Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene WC WV GCJI AC 12/19/08 The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. -

46399E642.Pdf

PGDS in DOS Myanmar Atlas Map Population and Geographic Data Section As of January 2006 Division of Operational Support Email : [email protected] ((( Yüeh-hsi ((( ((( Zayü ((( ((( BANGLADESHBANGLADESH ((( Xichang ((( Zhongdian ((( Ho-pien-tsun Cox'sCox's BazarBazar ((( ((( ((( ((( Dibrugrh ((( ((( ((( (((Meiyu ((( Dechang THIMPHUTHIMPHU ((( ((( ((( Myanmar_Atlas_A3PC.WOR ((( Ningnan ((( ((( Qiaojia ((( Dayan ((( Yongsheng KutupalongKutupalong ((( Huili ((( ((( Golaghat ((( Jianchuan ((( Huize ((( ((( ((( Cooch Behar ((( North Gauhati Nowgong (((( ((( Goalpara (((( Gauhati MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( Dinhata ((( ((( Gauripur ((( Dongch ((( ((( ((( Dengchuan ((( Longjie ((( Lalmanir Hat ((( Yanfeng ((( Rangpur ((( ((( ((( ((( Yuanmou ((( Yangbi((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Shillong ((((( Xundia ((( ((( Hai-tzu-hsin ((( Yongping ((( Xiangyun ((( ((( ((( Myitkyina ((( ((( ((( Heijing ((( Gaibanda NayaparaNayapara ((((( ((( (Sha-chiao(( ((( ((( ((( ((( Yipinglang ((( Baoshan TeknafTeknaf ButhidaungButhidaung (((TeknafTeknaf ((( ((( Nanjian ((( !! ((( Tengchong KanyinKanyin((( ChaungChaung !! Kunming ((( ((( ((( Anning ((( ((( ((( Changning MaungdawMaungdaw ((( MaungdawMaungdaw ((( ((( Imphal Mymensingh ((( ((( ((( ((( Jiuyingjiang ((( ((( Longling 000 202020 404040 BANGLADESHBANGLADESH((( 000 202020 404040 BANGLADESHBANGLADESH((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Yunxian ((( ((( ((( ((( -

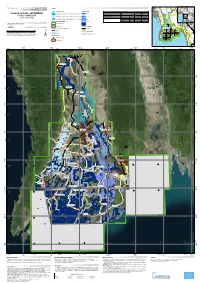

Appendix 6 Satellite Map of Proposed Project Site

APPENDIX 6 SATELLITE MAP OF PROPOSED PROJECT SITE Hakha Township, Rim pi Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village A6-1 Falam Township, Webula Village Tract, Chin State Kim Mon Chaung Village A6-2 Webula Village Pa Mun Chaung Village Tedim Township, Dolluang Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village Dolluang Village A6-3 Taunggyi Township, Kyauk Ni Village Tract, Shan State A6-4 Kalaw Township, Myin Ma Hti Village Tract and Baw Nin Village Tract, Shan State A6-5 Ywangan Township, Sat Chan Village Tract, Shan State A6-6 Pinlaung Township, Paw Yar Village Tract, Shan State A6-7 Symbol Water Supply Facility Well Development by the Procurement of Drilling Rig Nansang Township, Mat Mon Mun Village Tract, Shan State A6-8 Nansang Township, Hai Nar Gyi Village Tract, Shan State A6-9 Hopong Township, Nam Hkok Village Tract, Shan State A6-10 Hopong Township, Pawng Lin Village Tract, Shan State A6-11 Myaungmya Township, Moke Soe Kwin Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-12 Myaungmya Township, Shan Yae Kyaw Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-13 Labutta Township, Thin Gan Gyi Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Protection Dike Rainwater Pond (New) : 5 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) : 20 Facilities A6-14 Labutta Township, Laput Pyay Lae Pyauk Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-15 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Irrigation Channel Rainwater Pond (New) : 2 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) Hinthada Township, Tha Si Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-16 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road -

Śāntiniketan and Modern Southeast Asian

Artl@s Bulletin Volume 5 Article 2 Issue 2 South - South Axes of Global Art 2016 Śāntiniketan and Modern Southeast Asian Art: From Rabindranath Tagore to Bagyi Aung Soe and Beyond YIN KER School of Art, Design & Media, Nanyang Technological University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas Part of the Art Education Commons, Art Practice Commons, Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Other International and Area Studies Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation KER, YIN. "Śāntiniketan and Modern Southeast Asian Art: From Rabindranath Tagore to Bagyi Aung Soe and Beyond." Artl@s Bulletin 5, no. 2 (2016): Article 2. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. South-South Śāntiniketan and Modern Southeast Asian Art: From Rabindranath Tagore to Bagyi Aung Soe and Beyond Yin Ker * Nanyang Technological University Abstract Through the example of Bagyi Aung Soe, Myanmar’s leader of modern art in the twentieth century, this essay examines the potential of Śāntiniketan’s pentatonic pedagogical program embodying Rabindranath Tagore’s universalist and humanist vision of an autonomous modernity in revitalizing the prevailing unilateral and nation- centric narrative of modern Southeast Asian art. -

Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1

Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 2 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 3 4 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 စ Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 5 6 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 7 8 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 9 10 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Spatial Distribution Pattrens of Basic Education Schools in Pathein City Tin Tin Mya1, May Oo Nyo2 Abstract Pathein City is located in Pathein Township, western part of Ayeyarwady Region. The study area is included fifteen wards. This paper emphasizes on the spatial distribution patterns of these schools are analyzed by using appropriate data analysis methods. This study is divided into two types of schools, they are governmental schools and nongovernmental schools. Qualitative and quantitative methods are used to express the spatial distribution patterns of Basic Education Schools in Pathein City. Primary data are obtained from field surveys, informal interview, and open type interview .Secondary data are collected from the offices and departments concerned .Detailed facts are obtained from local authorities and experience persons by open type interview. Key words: spatial distribution patterns, education, schools, primary data ,secondary data Introduction The study area, Pathein City is situated in the Ayeyarwady Region. The study focuses only on the unevenly of spatial distribution patterns of basic education schools in Pathein City . -

Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area Delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R

Nepal (!Loikaw GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR130 I Legend r n r India China e Product N.: 16IRRAWADDYDELTA, v2, English Magway a Rakhine w Bangladesh e a w l d a Vietnam Crisis Information Hydrology Consequences within the AOI on 09, 10, 11/08/2015 d Myanmar S Affected Total in AOI y Nay Pyi Taw Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R ha 428922,1 i v Laos Flooded area e ^ r S Flood - 01/08/2015 Flooded Area delineation 10/08/2015 23:49 UTC Stream Estimated population Inhabitants 4252141 11935674 it Bay of ( to Settlements Built-up area ha 35491,8 75542,0 A 10 Bago n Bengal Thailand y g Delineation Map e Flooded Area delineation 09/08/2015 11:13 UTC Lake y P Transportation Railways km 26,0 567,6 a Cambodia r i w Primary roads km 33,0 402,1 Andam an n a Gulf of General Information d Sea g Reservoir Secondary roads km 57,2 1702,3 Thailand 09 y Area of Interest ) Andam an Cartographic Information River Sea Missing data Transportation Bay of Bengal 08 Bago Tak Full color ISO A1, low resolution (100 dpi) 07 1:600000 Ayeyarwady Yangon (! Administrative boundaries Railway Kayin 0 12,5 25 50 Region km Primary Road Pathein 06 04 11 12 (! Province Mawlamyine Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N map coordinate system Secondary Road 13 (! Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system ± Settlements 03 02 01 ! Populated Place 14 15 Built-Up Area Gulf of Martaban Andaman Sea 650000 700000 750000 800000 850000 900000 950000 94°10'0"E 94°35'0"E 95°0'0"E 95°25'0"E 95°50'0"E 96°15'0"E 96°40'0"E 97°5'0"E N " 0 ' 5 -

2016 General Report

General Report Setouchi Triennale Executive Committee Contents 1 Outline of Setouchi Triennale 2016----------------------------------------------------------- 1 2 General Overview------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 3 Art Sites and Projects--------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 4 Triennale Attendance------------------------------------------------------------------- ----------13 5 Triennale Events---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 20 6 Initiatives for Local Revitalization------------------------------------------------------------- 23 7 Effects of the Triennale-------------------------------------------------------------------------- 28 8 Local Residents’ Evaluations of the Triennale------------------------------------------------ 31 9 Activities of Volunteer Supporters-------------------------------------------------------------- 39 10 Publicity-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 41 11 Transportation------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 52 12 Triennale Visitor Services----------------------------------------------------------------------- 59 13 Triennale Passports, Goods, Etc.--------------------------------------------------------------- 61 14 Donations and Cooperation--------------------------------------------------------------------- 62 15 Executive Committee Account Balance (Forecast) --------------------------------------- -

Social Assessment for Ayeyarwady Region and Shan State

AND DEVELOPMENT May 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized SOCIAL ASSESSMENT FOR AYEYARWADY REGION AND SHAN STATE Public Disclosure Authorized Myanmar: Maternal and Child Cash Transfers for Improved Nutrition 1 Myanmar: Maternal and Child Cash Transfers for Improved Nutrition Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement May 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 5 List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... 9 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................... 10 List of BOXES ................................................................................................................................... 10 A. Introduction and Background....................................................................................................... 11 1 Objectives of the Social Assessment ................................................................................................11 2 Project Description ..........................................................................................................................11 3 Relevant Country and Sector Context..............................................................................................12 3.1